China (About the EoE)

Contents

- 1 China

- 1.1 Geography

- 1.2 Ecology and Biodiversity

- 1.3 People and Society

- 1.4 History

- 1.5 Government

- 1.6 Environment

- 1.7 International Environmental Agreements

- 1.8 Water

- 1.9 Agriculture

- 1.10 Energy

- 1.11 Resources

- 1.12 Economy

- 1.13 Science and Technology

- 1.14 Foreign Relations

- 1.15 International Disputes

- 1.16 References

- 1.17 Citation

China

Countries and Regions of the World Collection

China (officially the People's Republic of China or PRC) is one of the major nations of the world, with the largest population (one-and-a-third billion people or about one-fifth of the world's population) and the fourth largest land area (after Russia, Canada and the United States), and one of the oldest histories of continuous cultural and political history.

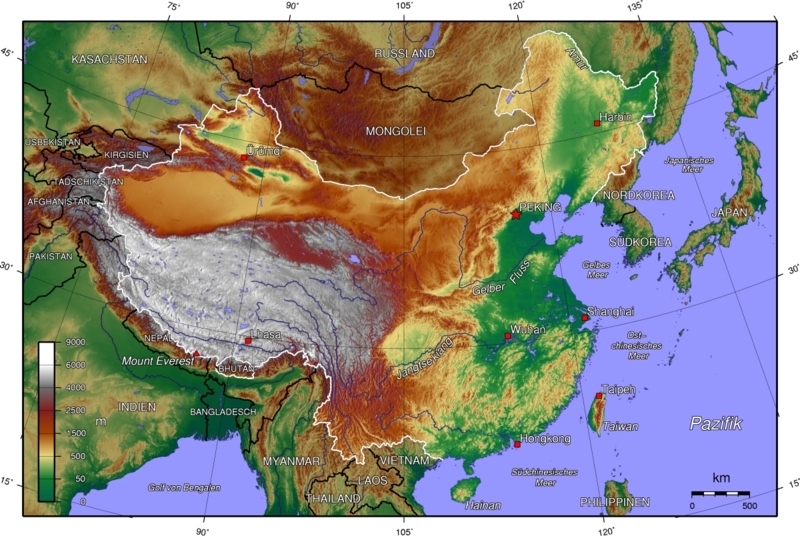

China has a very diverse topography with mountains, high plateaus, and deserts in the west; and, plains, deltas, and hills in east. It's climate is equally diverse, ranging from troptical in the south to subarctic in north. The world's tallest peak, Mount Everest on the border between China and Nepal.

Deterioration in the environment - notably air pollution, soil erosion, and the steady fall of the water table, especially in the north - is another long-term problem. China continues to lose arable land because of erosion and economic development. The Chinese government is seeking to add energy production capacity from sources other than coal and oil, focusing on nuclear and alternative energy development.

Its major environmental issues include:

- Air pollution, particularly from its reliance on coal produces sulfur dioxide, particulates, acid rain and Greenhouse gas emissions);

- water shortages, particularly in the north;

- Coral reef destruction from mining, overfishing and sewage discharge (Kimura et al, 2008);

- Water pollution from untreated wastes;;

- Deforestation;

- Estimated loss of one-fifth of agricultural land since 1949 to soil erosion and economic development;

- Desertification; and

- Trade and consumption of endangered species.

China is susceptible to frequent typhoons (about five per year along southern and eastern coasts); damaging floods; tsunamis; earthquakes; droughts; and, land subsidence.

For centuries China stood as a leading civilization, often outpacing the rest of the world in the arts and sciences, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the country was beset by civil unrest, major famines, military defeats, and foreign occupation.

After World War II, the Communists under Mao Zedong established an autocratic socialist system that, while ensuring China's sovereignty, imposed strict controls over everyday life and cost the lives of tens of millions of people.

After 1978, Mao's successor Deng Xiaoping and other leaders focused on market-oriented economic development and by 2000 output had quadrupled. For much of the population, living standards have improved dramatically and the room for personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight.

In 2008, China was estimated to be the second-largest economy in the world after the United States, although in per capita terms the country is still lower middle-income.

Restrictions of family size introduced in 1979 have contributed to a steady decline in China's population growth rate (with fertility rates dropping from over five children per woman to less than two) with significant implications for the country's and the world's environment, as well as the nation's ability to provide infrastructure and services for its people.

For much of the population, living standards have improved dramatically and personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight, and human rights abuses from the government are a major issue. China since the early 1990s has increased its global outreach and participation in international organizations.

Source: NASA

Geography

Location: Eastern Asia, bordering the East China Sea, Korea Bay, Yellow Sea, and South China Sea, between North Korea and Vietnam.

Geographic Coordinates: 35 00 N, 105 00 E

Area: 9,596,960 km2 (9,326,410 km2 land and 270,550 km2 water)

arable land: 14.86%

permanent crops: 1.27%

other: 83.87% (2005)

Land Boundaries: 22,117 km - border countries: Afghanistan 76 km, Bhutan 470 km, Myanmar (Burma) 2185 km, India 3380 km, Kazakhstan 1533 km, North Korea 1416 km, Kyrgyzstan 858 km, Laos 423 km, Mongolia 4,677 km, Nepal 1236 km, Pakistan 523 km, Russia (northeast) 3605 km, Russia (northwest) 40 km, Tajikistan 414 km, Vietnam 1281 km - Regional borders: Hong Kong 30 km, Macau 0.34 km

Coastline: 14,500 km

Maritime Claims:

Territorial sea: 12 nautical miles

Contiguous zone: 24 nautical miles

Exclusive economic zone: 200 nautical miles

Continental shelf: 200 nautical miles or to the edge of the continental margin

Natural Hazards: Frequent typhoons (about five per year along southern and eastern coasts); damaging floods; tsunamis; earthquakes; droughts; land subsidence.

Terrain: Mostly mountains, high plateaus, deserts in west; plains, deltas, and hills in east . The lowest point is Turpan Pendi (-154 metres) and its highest point is Mount Everest (8850 metres).

Climate: Extremely diverse; tropical in south to subarctic in north.

Topography of China. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Ecology and Biodiversity

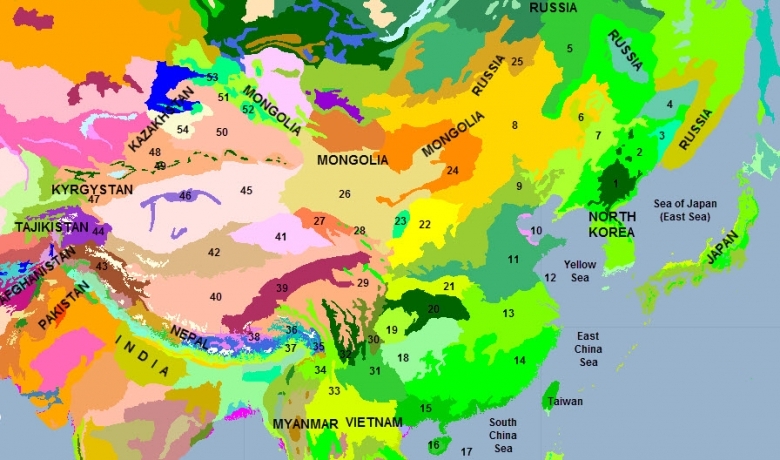

Ecoregions of China. Source: World Wildlife Fund

See also:

See also:

- Biological diversity in the mountains of Southwest China

- Biological diversity in the Himalayas

- Biological diversity in the mountains of Central Asia

- Biological diversity in Indo-Burma

- Huanglong National Scenic Area, China

- Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area, China

- Mount Emei and Leshan Giant Buddha, China

- Mount Huangshan Scenic Beauty and Historic Interest Site, China

- Mount Taishan Scenic Beauty and Historic Interest Zone, China

- Mount Wuyi, China

- The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, China

- Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, China

- Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area, China

People and Society

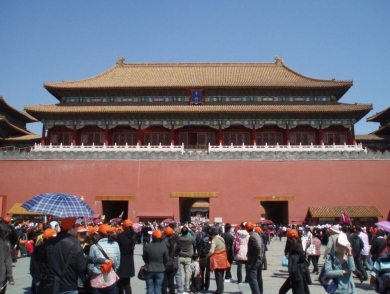

| The Meridian Gate - the largest gate in the Forbidden City with five arches - is the southern entrance to the Forbidden City in Beijing. Built from 1406 to 1420 AD, the Forbidden City was the Chinese imperial palace from the Ming Dynasty, which began in 1368, to the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912. |

| The concentric street patterns of Beijing are clearly visible in this photo taken from the International Space Station. The rectangular area in the center is the Palace Museum also known as the Forbidden City. The area of buildings north of the Forbidden City contains a number of universities. Beijing is surrounded by six ring roads or beltways, four of which may be seen in this photo. The 1st Ring Road no longer functions as an expressway. Image courtesy of NASA. |

| The Juyongguan section of the Great Wall is closest to Beijing and is therefore its most visited portion. Most of the existing Great Wall was built during the Ming Dynasty (14th to 17th centuries) to protect the northern borders of the Chinese Empire. The Manchus conquered the Empire in the mid-17th century and established the Qing Dynasty; they added so much more territory to the Empire beyond the Great Wall that the structure was no longer needed to protect the Empire from outside invaders. |

|

Construction of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River in central China. On 15 May 2006, Chinese engineers were pouring the last of the concrete to finish the construction of the massive dam, which is designed to provide flood control and to be the largest electricity-generating plant in the world. By 15 May 2006, the dam spanned the entire river, and a large reservoir had filled behind it to the northwest. White spray shoots through gates in the center portion of the dam. The former locks are much less prominent, and the new ones to the north appear as a linear arrangement of thin, blue rectangles. Photos courtesy of NASA. |

Population: 1,343,239,923 (July 2012 est.)

Ethnic groups: Han Chinese 91.5%, Zhuang, Manchu, Hui, Miao, Uighur, Tujia, Yi, Mongol, Tibetan, Buyi, Dong, Yao, Korean, and other nationalities 8.5% (2000 census)

The largest ethnic group is the Han Chinese, who constitute about 91.5% of the total population (2000 census). The remaining 8.5% are Zhuang (16 million), Manchu (10 million), Hui (9 million), Miao (8 million), Uighur (7 million), Yi (7 million), Mongol (5 million), Tibetan (5 million), Buyi (3 million), Korean (2 million), and other ethnic minorities.

Age Structure:

0-14 years: 17.6% (male 126,634,384/female 108,463,142)

15-64 years: 73.6% (male 505,326,577/female 477,953,883)

65 years and over: 8.9% (male 56,823,028/female 61,517,001) (2011 est.)

Median age: 35.5 years

Population Growth Rate: 0.481% (2012 est.)

Birthrate: 12.31 births/1,000 population (2012 est.)

Death Rate: 7.17 deaths/1,000 population (July 2012 est.)

Net Migration Rate: -0.33 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2012 est.)

Urbanization: 47% of total population (2010) growing at an annual rate of change of 2.3% (2010-15 est.)

Life Expectancy at Birth: 74.84 years

male: 72.82 years

female: 77.11 years (2012 est.)

Total Fertility Rate: 1.55 children born/woman (2012 est.)

Languages: Standard Chinese or Mandarin (Putonghua, based on the Beijing dialect), Yue (Cantonese), Wu (Shanghainese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (Hokkien-Taiwanese), Xiang, Gan, Hakka dialects, minority languages.

There are seven major Chinese dialects and many subdialects. Mandarin (or Putonghua), the predominant dialect, is spoken by over 70% of the population. It is taught in all schools and is the medium of government. About two-thirds of the Han ethnic group are native speakers of Mandarin; the rest, concentrated in southwest and southeast China, speak one of the six other major Chinese dialects. Non-Chinese languages spoken widely by ethnic minorities include Mongolian, Tibetan, Uighur and other Turkic languages (in Xinjiang), and Korean (in the northeast). Some autonomous regions and special administrative regions have their own official languages. For example, Mongolian has official status within the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region of China.

Literacy: 91.6%

The Pinyin System of Romanization

On January 1, 1979, the Chinese Government officially adopted the pinyin system for spelling Chinese names and places in Roman letters. A system of Romanization invented by the Chinese, pinyin has long been widely used in China on street and commercial signs as well as in elementary Chinese textbooks as an aid in learning Chinese characters. Variations of pinyin also are used as the written forms of several minority languages.

Pinyin has now replaced other conventional spellings in China's English-language publications. The U.S. Government also has adopted the pinyin system for all names and places in China. For example, the capital of China is now spelled "Beijing" rather than "Peking."

Religion

A February 2007 survey conducted by East China Normal University and reported in state-run media concluded that 31.4% of Chinese citizens ages 16 and over are religious believers. While the Chinese constitution affirms “freedom of religious belief,” the Chinese Government places restrictions on religious practice, particularly on religious practice outside officially recognized organizations. The five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” are Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism. Buddhism is most widely practiced; the state-approved Xinhua news agency estimates there are 100 million Buddhists in China. According to the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), there are more than 21 million Muslims in the country. Christians on the mainland number nearly 23 million, accounting for 1.8% of the population, according to The Blue Book of Religions (compiled by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of World Religions and released in August 2010). Other official figures indicate there are 5.3 million Catholics, though unofficial estimates are much higher. The Pew Research Center estimated in 2007 that 50 million to 70 million Christians practice in unregistered religious gatherings or “house” churches. There are no official statistics confirming the number of Taoists in China.

Although officially restricted from 1949 until the 1980s, Buddhism has regained popularity in China and has become the largest organized religion in the country. There continue to be strict government restrictions on Tibetan Buddhism.

Of China's 55 officially recognized minorities, 10 groups are predominately Muslim. According to government figures, there are 36,000 Islamic places of worship and more than 45,000 imams.

Only two Christian organizations--a “patriotic” Catholic association without official ties to Rome and the "Three-Self-Patriotic" Protestant church--are sanctioned by the Chinese Government. Unregistered “house” churches exist in many parts of the country. The extent to which local authorities have tried to control the activities of unregistered churches varies from region to region. However, the government suppresses the religious activities of "underground" Roman Catholic clergy who are not affiliated with the official patriotic Catholic association and have avowed loyalty to the Vatican, which the government accuses of interfering in the country's internal affairs. The government also severely restricts the activities of groups it designates as "evil cults," including several Christian groups and the Falun Gong spiritual movement.

Population Policy

With a population officially over 1.3 billion and an estimated population growth rate of 0.593% (2011 est.), China is very concerned about its population growth and has attempted with mixed results to implement a strict birth limitation policy. China's 2002 Population and Family Planning Law and policy permits one child per family, with allowance for a second child under certain circumstances, especially in rural areas, and with guidelines looser for ethnic minorities with small populations. Enforcement varies and relies largely on "social compensation fees" to discourage extra births. Official government policy prohibits the use of physical coercion to compel persons to submit to abortion or sterilization, but in some localities there are instances of local birth-planning officials using physical coercion to meet birth limitation targets. The government's goal is to stabilize the population in the first half of the 21st century, and 2009 projections from the U.S. Census Bureau were that the Chinese population would peak at around 1.4 billion by 2026.

History

Dynastic Period

China is the oldest continuous major world civilization, with records dating back about 3,500 years. Successive dynasties developed a system of bureaucratic control that gave the agrarian-based Chinese an advantage over neighboring nomadic and hill cultures. Chinese civilization was further strengthened by the development of a Confucian state ideology and a common written language that bridged the gaps among the country's many local languages and dialects. Whenever China was conquered by nomadic tribes, as it was by the Mongols in the 13th century, the conquerors sooner or later adopted the ways of the "higher" Chinese civilization and staffed the bureaucracy with Chinese.

The last dynasty was established in 1644, when the Manchus overthrew the native Ming dynasty and established the Qing (Ch'ing) dynasty with Beijing as its capital. The bloody overthrow of the Ming Dynasty has been reconstructed to have roots in the cooling period of the Little Ice Age, which cooling led to massive crop failures, peasant revolts and Manchu aggression.(Zheng et al, 2014) At the expense in blood and treasure, the Manchus over the next half-century gained control of many border areas, including Xinjiang, Yunnan, Tibet, Mongolia, and Taiwan. The success of the early Qing period was based on the combination of Manchu martial prowess and traditional Chinese bureaucratic skills.

During the 19th century, Qing control weakened, and prosperity diminished. China suffered massive social strife, economic stagnation, explosive population growth, and Western penetration and influence. The Taiping and Nian rebellions, along with a Russian-supported Muslim separatist movement in Xinjiang, drained Chinese resources and almost toppled the dynasty. Britain's desire to continue its opium trade with China collided with imperial edicts prohibiting the addictive drug, and the First Opium War erupted in 1840. China lost the war; subsequently, Britain and other Western powers, including the United States, forcibly occupied "concessions" and gained special commercial privileges. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain in 1842 under the Treaty of Nanking, and in 1898, when the Opium Wars finally ended, Britain executed a 99-year lease of the New Territories, significantly expanding the size of the Hong Kong colony.

As time went on, the Western powers, wielding superior military technology, gained more economic and political privileges. Reformist Chinese officials argued for the adoption of Western technology to strengthen the dynasty and counter Western advances, but the Qing court played down both the Western threat and the benefits of Western technology.

Early 20th Century China

Frustrated by the Qing court's resistance to reform, young officials, military officers, and students--inspired by the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen--began to advocate the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and creation of a republic. A revolutionary military uprising on October 10, 1911, led to the abdication of the last Qing monarch. As part of a compromise to overthrow the dynasty without a civil war, the revolutionaries and reformers allowed high Qing officials to retain prominent positions in the new republic. One of these figures, Gen. Yuan Shikai, was chosen as the republic's first president. Before his death in 1916, Yuan unsuccessfully attempted to name himself emperor. His death left the republican government all but shattered, ushering in the era of the "warlords" during which China was ruled and ravaged by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders.

In the 1920s, Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base in south China and set out to unite the fragmented nation. With Soviet assistance, he organized the Kuomintang (KMT or "Chinese Nationalist People's Party"), and entered into an alliance with the fledgling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After Sun's death in 1925, one of his proteges, Chiang Kai-shek, seized control of the KMT and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under its rule. In 1927, Chiang turned on the CCP and executed many of its leaders. The remnants fled into the mountains of eastern China. In 1934, driven out of their mountain bases, the CCP's forces embarked on a "Long March" across some of China's most desolate terrain to the northwestern province of Shaanxi, where they established a guerrilla base at Yan'an.

During the "Long March," the communists reorganized under a new leader, Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung). The bitter struggle between the KMT and the CCP continued openly or clandestinely through the 14-year-long Japanese invasion (1931-45), even though the two parties nominally formed a united front to oppose the Japanese invaders in 1937. The war between the two parties resumed after the Japanese defeat in 1945. By 1949, the CCP occupied most of the country.

Chiang Kai-shek fled with the remnants of his KMT government and military forces to Taiwan, where he proclaimed Taipei to be China's "provisional capital" and vowed to re-conquer the Chinese mainland. Taiwan still calls itself the "Republic of China."

The People's Republic of China

In Beijing, on October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China (P.R.C.). The new government assumed control of a people exhausted by two generations of war and social conflict, and an economy ravaged by high inflation and disrupted transportation links. A new political and economic order modeled on the Soviet example was quickly installed.

In the early 1950s, China undertook a massive economic and social reconstruction program. The new leaders gained popular support by curbing inflation, restoring the economy, and rebuilding many war-damaged industrial plants. The CCP's authority reached into almost every aspect of Chinese life. Party control was assured by large, politically loyal security and military forces; a government apparatus responsive to party direction; and the placement of party members in leadership positions in labor, women's, and other mass organizations.

The "Great Leap Forward" and the Sino-Soviet Split

In 1958, Mao broke with the Soviet model and announced a new economic program, the "Great Leap Forward," aimed at rapidly raising industrial and agricultural production. Giant cooperatives (communes) were formed, and "backyard factories" dotted the Chinese landscape. The results were disastrous. Normal market mechanisms were disrupted, agricultural production fell behind, and China's people exhausted themselves producing what turned out to be shoddy, un-salable goods. Within a year, starvation appeared even in fertile agricultural areas. From 1960 to 1961, the combination of poor planning during the Great Leap Forward and bad weather resulted in one of the deadliest famines in human history.

The already-strained Sino-Soviet relationship deteriorated sharply in 1959, when the Soviets started to restrict the flow of scientific and technological information to China. The dispute escalated, and the Soviets withdrew all of their personnel from China in August 1960. In 1960, the Soviets and the Chinese began to have disputes openly in international forums.

The Cultural Revolution

In the early 1960s, State President Liu Shaoqi and his protege, Party General Secretary Deng Xiaoping, took over direction of the party and adopted pragmatic economic policies at odds with Mao's revolutionary vision. Dissatisfied with China's new direction and his own reduced authority, Party Chairman Mao launched a massive political attack on Liu, Deng, and other pragmatists in the spring of 1966. The new movement, the "Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution," was unprecedented in communist China’s history. For the first time, a section of the Chinese communist leadership sought to rally popular opposition against another leadership group. China was set on a course of political and social anarchy that lasted the better part of a decade.

In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, Mao and his "closest comrade in arms," National Defense Minister Lin Biao, charged Liu, Deng, and other top party leaders with dragging China back toward capitalism. Radical youth organizations, called Red Guards, attacked party and state organizations at all levels, seeking out leaders who would not bend to the radical wind. In reaction to this turmoil, some local People's Liberation Army (PLA) commanders and other officials maneuvered to outwardly back Mao and the radicals while actually taking steps to rein in local radical activity. In this period massive and widespread destruction of historical and religious properties was encouraged by the communist government, in order to diminish the stature of any ideology in conflict with communism.

Gradually, Red Guard and other radical activity subsided, and the Chinese political situation stabilized along complex factional lines. The leadership conflict came to a head in September 1971, when Party Vice Chairman and Defense Minister Lin Biao reportedly tried to stage a coup against Mao; Lin Biao allegedly later died in a plane crash in Mongolia.

In the aftermath of the Lin Biao incident, many officials criticized and dismissed during 1966-69 were reinstated. Chief among these was Deng Xiaoping, who reemerged in 1973 and was confirmed in 1975 in the concurrent posts of Party Vice Chairman, Politburo Standing Committee member, PLA Chief of Staff, and Vice Premier.

The ideological struggle between more pragmatic, veteran party officials and the radicals re-emerged with a vengeance in late 1975. Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, and three close Cultural Revolution associates (later dubbed the "Gang of Four") launched a media campaign against Deng. In January 1976, Premier Zhou Enlai, a popular political figure, died of cancer. On April 5, Beijing citizens staged a spontaneous demonstration in Tiananmen Square in Zhou's memory, with strong political overtones of support for Deng. The authorities forcibly suppressed the demonstration. Deng was blamed for the disorder and stripped of all official positions, although he retained his party membership.

The Post-Mao Era

Mao's death in September 1976 removed a towering figure from Chinese politics and set off a scramble for succession. Former Minister of Public Security Hua Guofeng was quickly confirmed as Party Chairman and Premier. A month after Mao's death, Hua, backed by the PLA, arrested Jiang Qing and other members of the "Gang of Four." After extensive deliberations, the Chinese Communist Party leadership reinstated Deng Xiaoping to all of his previous posts at the 11th Party Congress in August 1977. Deng then led the effort to place government control in the hands of veteran party officials opposed to the radical excesses of the previous 2 decades.

The new, pragmatic leadership emphasized economic development and renounced mass political movements. At the pivotal December 1978 Third Plenum (of the 11th Party Congress Central Committee), the leadership adopted economic reform policies aimed at expanding rural income and incentives, encouraging experiments in enterprise autonomy, reducing central planning, and attracting foreign direct investment to China. The plenum also decided to accelerate the pace of legal reform, culminating in the passage of several new legal codes by the National People's Congress in June 1979.

After 1979, the Chinese leadership moved toward more pragmatic positions in almost all fields. The party encouraged artists, writers, and journalists to adopt more critical approaches, although open attacks on party authority were not permitted. In late 1980, Mao's Cultural Revolution was officially proclaimed a catastrophe. Hua Guofeng, a protege of Mao, was replaced as premier in 1980 by reformist Sichuan party chief Zhao Ziyang and as party General Secretary in 1981 by the even more reformist Communist Youth League chairman Hu Yaobang.

Reform policies brought improvements in the standard of living, especially for urban workers and for farmers who took advantage of opportunities to diversify crops and establish village industries. Controls on literature and the arts were relaxed, and Chinese intellectuals established extensive links with scholars in other countries.

At the same time, however, political dissent as well as social problems such as inflation, urban migration, and prostitution emerged. Although students and intellectuals urged greater reforms, some party elders increasingly questioned the pace and the ultimate goals of the reform program. In December 1986, student demonstrators, taking advantage of the loosening political atmosphere, staged protests against the slow pace of reform, confirming party elders' fear that the current reform program was leading to social instability. Hu Yaobang, a protege of Deng and a leading advocate of reform, was blamed for the protests and forced to resign as CCP General Secretary in January 1987. Premier Zhao Ziyang was made General Secretary and Li Peng, former Vice Premier and Minister of Electric Power and Water Conservancy, was made Premier.

1989 Student Movement and Tiananmen Square

After Zhao became the party General Secretary, the economic and political reforms he had championed, especially far-reaching political reforms enacted at the 13th Party Congress in the fall of 1987 and subsequent price reforms, came under increasing attack. His proposal in May 1988 to accelerate price reform led to widespread popular complaints about rampant inflation and gave opponents of rapid reform the opening to call for greater centralization of economic controls and stricter prohibitions against Western influence. This precipitated a political debate, which grew more heated through the winter of 1988-89.

The death of Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989, coupled with growing economic hardship caused by high inflation, provided the backdrop for a large-scale protest movement by students, intellectuals, and other parts of a disaffected urban population. University students and other citizens camped out in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to mourn Hu's death and to protest against those who would slow reform. Their protests, which grew despite government efforts to contain them, called for an end to official corruption, a greater degree of democracy, and for defense of freedoms guaranteed by the Chinese constitution. Protests also spread to many other cities, including Shanghai, Chengdu, and Guangzhou.

Martial law was declared on May 20, 1989. Late on June 3 and early on the morning of June 4, military units were brought into Beijing. They used armed force to clear demonstrators from the streets. There are no official estimates of deaths in Beijing, but most observers believe that casualties numbered in the hundreds.

After June 4, while foreign governments expressed horror at the brutal suppression of the demonstrators, the central government eliminated remaining sources of organized opposition, detained large numbers of protesters, and required political reeducation not only for students but also for large numbers of party cadre and government officials. Zhao was purged at the Fourth Plenum of the 13th Central Committee in June and replaced as Party General Secretary by Jiang Zemin. Deng’s power was curtailed as more orthodox party leaders, led by Chen Yun, became the dominant group in the leadership.

Following this resurgence of conservatives in the aftermath of June 4, economic reform slowed until given new impetus by Deng Xiaoping's return to political dominance 2 years later, including a dramatic visit to southern China in early 1992. Deng's renewed push for a market-oriented economy received official sanction at the 14th Party Congress later in the year as a number of younger, reform-minded leaders began their rise to top positions. Hu Jintao was elevated to the Politburo Standing Committee at the Congress. Deng and his supporters argued that managing the economy in a way that increased living standards should be China's primary policy objective, even if "capitalist" measures were adopted. Subsequent to the visit, the Communist Party Politburo publicly issued an endorsement of Deng's policies of economic openness. Though continuing to espouse political reform, China has consistently placed overwhelming priority on the opening of its economy.

Post-Deng Leadership

Deng's health deteriorated in the years prior to his death in 1997. During that time, Party General Secretary and P.R.C. President Jiang Zemin and other members of his generation gradually assumed control of the day-to-day functions of government. This "third generation" leadership governed collectively with Jiang at the center.

In the fall of 1987, Jiang was re-elected Party General Secretary at the 15th Party Congress, and in March 1998 he was re-elected President during the 9th National People's Congress. Premier Li Peng was constitutionally required to step down from that post. He was elected to the chairmanship of the National People's Congress. The reform-minded pragmatist Zhu Rongji was selected to replace Li as Premier.

In November 2002, the 16th Communist Party Congress elected Hu Jintao as the new General Secretary. In 1992 Deng Xiaoping had informally designated Hu Jintao as the leading figure among the "fourth generation" leaders. A new Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee was also elected in November.

In March 2003, General Secretary Hu Jintao was elected President at the 10th National People's Congress. Jiang Zemin retained the chairmanship of the Central Military Commission. At the Fourth Party Plenum in September 2004, Jiang Zemin retired from the Central Military Commission, passing the Chairmanship and control of the People's Liberation Army to President Hu Jintao.

The Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Party Congress, held in October 2007, saw the elevation of key “fifth generation” leaders to the Politburo and Standing Committee, including Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Li Yuanchao, and Wang Yang. At the National People’s Congress plenary held in March 2008, Xi was elected Vice President of the government, and Li Keqiang was elected Vice Premier. The 18th Party Congress is scheduled to be held in the fall of 2012. It is expected that President Hu Jintao, in keeping with precedent, will step down as the party's General Secretary at that time, and the Congress will elect the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.

Government

Chinese Communist Party

The estimated 78 million-member CCP, authoritarian in structure and ideology, continues to dominate government. Nevertheless, China's population, geographical vastness, and social diversity frustrate attempts to rule by fiat from Beijing. Central leaders must increasingly build consensus for new policies among party members, local and regional leaders, influential non-party members, and the population at large.

In periods of greater openness, the influence of people and organizations outside the formal party structure has tended to increase, particularly in the economic realm. This phenomenon is most apparent today in the rapidly developing coastal region. Nevertheless, in all important government, economic, and cultural institutions in China, party committees work to see that party and state policy guidance is followed and that non-party members do not create autonomous organizations that could challenge party rule. Party control is tightest in government offices and in urban economic, industrial, and cultural settings; it is considerably looser in the rural areas, where roughly half of the people live.

Theoretically, the party's highest body is the Party Congress, which traditionally meets at least once every 5 years. The 17th Party Congress took place in fall 2007. The primary organs of power in the Communist Party include:

- The Politburo Standing Committee, which currently consists of nine members;

- The Politburo, consisting of 25 full members, including the members of the Politburo Standing Committee;

- The Secretariat, the principal administrative mechanism of the CCP, headed by Politburo Standing Committee member and executive secretary Xi Jinping;

- The Central Military Commission;

- The Central Discipline Inspection Commission, which is charged with rooting out corruption and malfeasance among party cadres.

State Structure

Since 1949, the Chinese Government has always been subordinate to the Chinese Communist Party; the govenment's chief role is to implement party policies. The primary organs of state power are the National People's Congress (NPC), the President (the head of state), and the State Council. Members of the State Council include Premier Wen Jiabao (the head of government), a variable number of vice premiers (now four), five state councilors (protocol equivalents of vice premiers but with narrower portfolios), and 25 ministers, the central bank governor, and the auditor-general.

Under the Chinese constitution, the NPC is the highest organ of state power in China. It meets annually for about 2 weeks to review and approve major new policy directions, laws, the budget, and major personnel changes. These initiatives are presented to the NPC for consideration by the State Council after previous endorsement by the Communist Party's Central Committee. Although the NPC generally approves State Council policy and personnel recommendations, various NPC committees hold active debate in closed sessions, and changes may be made to accommodate alternative views.

When the NPC is not in session, its permanent organ, the Standing Committee, exercises state power.

Government Type: Communist state

Capital: Beijing - 12.214 million (2009)

Other Major Cities: Shanghai 16.575 million; Chongqing 9.401 million; Shenzhen 9.005 million; Guangzhou 8.884 million (2009)

Administrative Divisions: 23 provinces (sheng, singular and plural), 5 autonomous regions (zizhiqu, singular and plural), and 4 municipalities (shi, singular and plural)

- provinces: Anhui, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guizhou, Hainan, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Jilin, Liaoning, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Shandong, Shanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Zhejiang; (see note on Taiwan)

- autonomous regions: Guangxi, Nei Mongol (Inner Mongolia), Ningxia, Xinjiang Uygur, Xizang (Tibet)

- municipalities: Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Tianjin

Legal System: Based on civil law influenced by Soviet and continental European civil law systems; legislature retains power to interpret statutes; constitution ambiguous on judicial review of legislation. China has not submitted an International Court of Justice (ICJ) jurisdiction declaration; and is a non-party state to the International Criminal Court (ICCt).

The government's efforts to promote rule of law are ongoing. After the Cultural Revolution, China's leaders aimed to develop a legal system to restrain abuses of official authority and revolutionary excesses. In 1982, the National People's Congress adopted a new state constitution that emphasized the rule of law under which even party leaders are theoretically held accountable.

Since 1979, when the drive to establish a functioning legal system began, more than 300 laws and regulations, most of them in the economic area, have been promulgated. The use of mediation committees--informed groups of citizens who resolve about 90% of China's civil disputes and some minor criminal cases at no cost to the parties--is one innovative device. There are more than 800,000 such committees in both rural and urban areas.

Legal reform became a government priority in the 1990s. Legislation designed to modernize and professionalize the nation's lawyers, judges, and prisons was enacted. The 1994 Administrative Procedure Law allows citizens to sue officials for abuse of authority or malfeasance. In addition, the criminal law and the criminal procedures laws were amended to introduce significant reforms. The criminal law amendments abolished the crime of "counter-revolutionary" activity, although many persons are still incarcerated for that crime. Criminal procedures reforms also encouraged establishment of a more transparent, adversarial trial process. The Chinese constitution and laws provide for fundamental human rights, including due process, but these are often ignored in practice. In addition to other judicial reforms, the constitution was amended in 2004 to include the protection of individual human rights and legally-obtained private property, but it is unclear how some of these provisions will be implemented. Since this amendment, there have been new publications in bankruptcy law and anti-monopoly law, and modifications to company law and labor law. Although new criminal and civil laws have provided additional safeguards to citizens, previously debated political reforms, including expanding elections to the township level beyond the current trial basis, have been put on hold.

Environment

One of the serious negative consequences of China's rapid industrial development has been increased pollution and degradation of natural resources. China surpassed the United States as the world's largest emitter of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in 2007. A World Health Organization report on air quality in 272 cities worldwide concluded that seven of the world's 10 most polluted cities were in China. According to China's own evaluation, two-thirds of the 338 cities for which air-quality data are available are considered polluted--two-thirds of those moderately or severely so. Almost all of the nation's rivers are considered polluted to some degree and half of the population lacks access to clean water. Ninety percent of urban bodies of water are severely polluted. Various studies estimate pollution costs the Chinese economy 7%-10% of GDP each year.

Water scarcity also is an issue, particularly in Northern China, where groundwater is being extracted at an increasingly unsustainable rate, seriously constricting future economic growth if stronger conservation measures are not taken or additional water not diverted. The central government is currently focused on the latter option, investing an estimated $60 billion in the South-North Water Diversion Project, a large-scale diversion of water from the Yangtze River to northern cities, including Beijing and Tianjin.

The question of environmental impacts associated with the Three Gorges Dam project has generated controversy among environmentalists inside and outside China. Critics claim that erosion and silting of the Yangtze River threaten several endangered species, while Chinese officials say the dam will help prevent devastating floods and generate clean hydroelectric power that will enable the region to lower its dependence on coal, thus lessening air pollution. There are also major concerns about whether water supply in the Yangtze is adequate to support the project.

China's leaders are increasingly paying attention to the country's severe environmental problems. In 1998, the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA) was officially upgraded to a ministry-level agency, the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). In recent years, China has strengthened its environmental legislation and made some progress in stemming environmental deterioration. Beijing invested heavily in pollution control as part of its campaign to host a successful Olympiad in 2008, though some of the gains were temporary in nature. Some cities have seen improvement in air quality in recent years. The United States and China have been engaged in an active program of bilateral environmental cooperation since the mid-1990s, with a more recent emphasis on clean energy technology and the design of effective environmental policy. China has similar energy and environmental cooperation programs with Japan and European Union countries.

In 2008, China and the United States formed the Ten-Year Framework on Energy and Environment (TYF). The TYF facilitates the exchange of information and best practices between the two countries to foster innovation and develop solutions to the pressing energy and environment problems both countries face. The framework is comprised of seven action plans (clean air, clean water, clean and efficient transportation, clean and efficient electricity, energy efficiency, protected areas, and wetlands conservation) as well as the EcoPartnerships program, which seeks to encourage action plan collaboration at the sub-national level (states, cities, businesses, and universities) between the U.S. and China. Seven original EcoPartnerships were announced with the formation of the TYF in 2008, with six new partnerships signed during the third annual S&ED in May 2011. (For more information about the TYF and EcoPartnerships see: http://www.state.gov/e/oes/env/tenyearframework/index.htm)

During the July 2009 S&ED, the two countries negotiated an MOU to enhance cooperation on climate change, energy, and the environment, which further elaborated the role of the TYF and established a new dialogue and cooperation mechanism on climate change. During the May 2011 S&ED, the U.S. and China affirmed their efforts to work together to achieve a positive outcome at the UN Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa.

The first U.S.-China Renewable Energy Forum was held concurrently with the second annual S&ED in May 2010 in Beijing. Forums were held on energy efficiency, biofuels, and on promoting opportunities for U.S.-China collaboration to advance clean energy, including through $150 million in bilateral private and public funding for the CERC. Five-year work plans for the U.S. and Chinese CERC research teams were signed during President Hu Jintao’s January 2011 visit.

International Environmental Agreements

China is party to international agreements on Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands, and Whaling.

China is an active participant in climate change talks and other multilateral environmental negotiations, taking environmental challenges seriously but pushing for the developed world to help developing countries. China is a member of the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate, and participates actively in the bilateral Climate Change Policy Dialogue. It signed on to the 2009 Copenhagen Accord in 2010 and inscribed a commitment to reducing its carbon intensity levels by 40%-45% by 2020 from 2005 levels. During President Hu’s January 2011 visit, the U.S. and China agreed to implement the 2010 Cancun agreements and support efforts to achieve positive outcomes at the 2011 UN conference in South Africa.

China is a signatory to the Basel Convention governing the transport and disposal of hazardous waste and the Montreal Protocol for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, as well as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species and other major environmental agreements.

Water

Total Renewable Water Resources: 2,829.6 cu km (1999)

Freshwater Withdrawal: Total: 549.76 cu km/yr (7% Domestic, 26% Industrial, 68% Agricultural). Per capita: 415 cu m/yr (2000)

Water scarcity is a critical issue in China. Recently, severe drought in northern China posed a serious threat to sustained economic growth and local livelihoods. Since the 1980s, China has experienced increased severity and frequency of water shortages due to variations in rainfall; excessive withdrawals of groundwater sources, polluted water resources, and inefficiencies in water usage. In normal water years, half of China’s 662 cities have insufficient water supplies. Almost 94% of metropolitan areas with populations of more than one million people struggle to meet their annual water demands. Eleven percent of China’s population lack access to improved drinking water sources (up from 33% in 1990); while 45% of the population lacks access to improved sanitation.

In addition, poor water quality continues to pose a challenge to environmental and human health. On a daily basis 300 million people drink contaminated water in China. Nine million cases of diarrhea linked to water pollution occur annually in China, based on China’s 2003 National Health Survey. Approximately 61,000 people in China die annually from diarrhea related to polluted water--half of them are rural children.

The Government of China has responded to this crisis through large investments in the water sector, including storage, conveyance and treatment. Recent water and energy policies stressed conservation measures requiring municipalities and industry to consume less water. Large construction projects, such as the South-North Water Transfer project, are directed at addressing the water crisis. However, the question of environmental impacts associated with such projects has generated controversy among environmentalists inside and outside China. Critics assert that the magnitude and cost of building and operating large conveyance systems could result in unintended consequences that may overwhelm planned benefits. These consequences may include higher water prices, damage to local and downstream environments, additional treatment facilities for water that is currently too polluted to use, or further water shortages. China has announced its intention to funnel billions of renminbi of additional investment into water conservation projects during the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015).

Agriculture

China is the world's most populous country and one of the largest producers and consumers of agricultural products. According to the UN World Food Program, in 2003, China fed 20% of the world's population with only 7% of the world's arable land (estimated at 121.7 million hectares in 2010, down from 129.9 million hectares in 1997). Almost 40% of China's labor force is engaged in agriculture, even though only 15% of the land is suitable for cultivation and agriculture contributes only about 10.3% of China's GDP (2009). China is among the world's largest producers of rice, corn, wheat, soybeans, vegetables, tea, and pork. Cotton is the major non-food commodity. China hopes to further increase agricultural production through improved plant stocks, fertilizers, new technologies (such as biotechnology), irrigation, and using more sustainable methods of production. The Chinese Government has also acknowledged that climate change poses a severe threat to the farming sector. Incomes for Chinese farmers are increasing more slowly than for urban residents, leading to an increasing wealth gap between the cities and countryside. Inadequate port facilities and a lack of warehousing and cold storage installations impede both domestic and international agricultural trade.

China is now one of the most important markets for U.S. exports; in 2010, U.S. exports to China totaled $91.9 billion, an all-time high. U.S. agricultural exports continue to play a major role in bilateral trade, totaling $17.9 billion in 2010 and thus making China the United States' largest agricultural export market. Leading categories include: soybeans ($11.3 billion), cotton ($1.988 billion), and hides and skins ($822 million).

Agricultural products: Rice, wheat, potatoes, corn, peanuts, tea, millet, barley, apples, cotton, oilseed; pork; fish

Irrigated Land: 545,960 sq km (2003)

Energy

See Energy profile of China, Three Georges Dam

Driven by strong economic growth, China's demand for energy is surging rapidly. China is the world's largest energy consumer and the world's second-largest net importer of crude oil after the United States. China is also the fifth-largest energy producer in the world. The International Energy Agency estimates that China will contribute 36% to the projected growth in global energy use, with its demand rising by 75% between 2008 and 2035. China's electricity generation is expected to increase to 10,555 billion kilowatt hours (Bkwh) by 2035, over three times the amount in 2009, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration. In 2010, China led the world in clean energy investment with $51.1 billion and had installed wind capacity of 41.8 gigawatts, the most in the world.

Coal continues to make up the bulk of China's energy consumption (71% in 2009), and China is the largest producer and consumer of coal in the world. As China's economy continues to grow, China's coal demand is projected to rise significantly, although coal's share of China's overall energy consumption is expected to decrease. China's continued reliance on coal as a power source has contributed significantly to China's emergence as the world's largest emitter of acid rain-causing sulfur dioxide and green house gases, including carbon dioxide.

China's 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015) continues the government’s policies encouraging greater energy conservation measures, development of renewable energy sources, and increased attention to environmental protection. China is exploring cleaner energy sources, including natural and shale gas, wind, solar, biomass, hydropower, and nuclear power, to reduce reliance on coal. China's renewable energy law calls for 15% of its energy to come from non-fossil fuel sources by 2020. In addition, the share of electricity generated by nuclear power is projected to grow from 1% in 2000 to 5% in 2020.

Since 1993, China has been a net importer of oil, a large portion of which comes from the Middle East. Net imports were approximately 4.3 million barrels per day in 2009. China's use of oil will continue to increase rapidly, particularly in response to the quick expansion of its vehicle fleets. Vehicle sales in China in 2010 rose 32% to over 18 million. China is interested in diversifying the sources of its oil imports and has invested in oil fields around the world. China recently concluded long-term loan-for-oil deals totaling $50 billion with Russia, Brazil, Venezuela, Kazakhstan, Angola, and Ecuador. In recent years, China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) has also invested in several U.S. oil and natural gas fields in Texas, Colorado, and Wyoming. Beijing also plans to increase China's natural gas use through imports and domestic production. Gas currently accounts for only 4% of China's total energy consumption. China has set an ambitious target of increasing the share of natural gas in its overall energy mix to 10%.

During the July 2009 inaugural meeting of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED), the two countries negotiated a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to enhance cooperation on climate change, energy, and the environment in order to expand and enhance cooperation on clean and efficient energy, to protect the environment, and to ensure energy security. The two sides also signed an MOU on cooperation on energy efficiency in buildings.

In November 2009, during U.S. President Obama’s state visit to China, the United States and China announced the establishment of the U.S.-China Clean Energy Research Center (CERC), which will focus on energy efficiency, clean coal including carbon capture and storage, and clean vehicles; signed the Renewable Energy Partnership; launched the U.S.-China Electric Vehicles Initiative; announced the bilateral Energy Efficiency Action Plan under the Ten-Year Framework on Energy and Environment; and inaugurated the U.S.-China Energy Cooperation Program, a public-private partnership focused on joint collaborative projects on renewable energy, smart grid, clean transportation, green building, clean coal, combined heat and power, and energy efficiency. The two countries also announced the launch of the U.S.-China Shale Gas Initiative, which will accelerate China's development of shale gas resources.

During President Hu’s January 2011 state visit to the United States, the U.S. Department of Energy announced joint work plans under the U.S.-China CERC on building efficiency, clean coal, and clean vehicles, and started negotiations on a U.S.-China Eco-City Initiative to integrate energy efficiency and renewable energy into city design and operation in the two countries. In May 2011, the United States hosted the second U.S.-China Energy Efficiency Forum, and similar forums on biofuels and renewable energy are currently being planned.

Resources

Natural Resources: Coal, iron ore, petroleum, natural gas, mercury, tin, tungsten, antimony, manganese, molybdenum, vanadium, magnetite, aluminum, lead, zinc, uranium, hydropower potential (world's largest). See also: Phosphorus use in China.

Economy

Efforts to stimulate the economy have led to widespread air pollution issue, Beijing motorways. @ C.Michael Hogan

Efforts to stimulate the economy have led to widespread air pollution issue, Beijing motorways. @ C.Michael Hogan

Since the late 1970s China has moved from a closed, centrally planned system to a more market-oriented one that plays a major global role - in 2010 China became the world's largest exporter. Reforms began with the phasing out of collectivized agriculture, and expanded to include the gradual liberalization of prices, fiscal decentralization, increased autonomy for state enterprises, creation of a diversified banking system, development of stock markets, rapid growth of the private sector, and opening to foreign trade and investment. China has implemented reforms in a gradualist fashion. In recent years, China has renewed its support for state-owned enterprises in sectors it considers important to "economic security," explicitly looking to foster globally competitive national champions.

Since 1978, China has reformed and opened its economy. The Chinese leadership has adopted a more pragmatic perspective on many political and socioeconomic problems and has reduced the role of ideology in economic policy. China's ongoing economic transformation has had a profound impact not only on China but on the world. The market-oriented reforms China has implemented over the past 2 decades have unleashed individual initiative and entrepreneurship. The result has been the largest reduction of poverty and one of the fastest increases in income levels ever seen. In 2010, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy in terms of gross domestic product, behind the United States. It has sustained average economic growth of over 9.3% since 1989. In 2010 its $5.88 trillion economy was just over one-third the size of the U.S. economy.

China is firmly committed to economic reform and opening to the outside world. The Chinese leadership has identified reform of state industries, the establishment of a social safety net, reduction of the income gap, protection of the environment, and development of clean energy as government priorities. Government strategies for achieving these goals include large-scale privatization of unprofitable state-owned enterprises, development of a pension system for workers, establishment of an effective and affordable health care system, building environmental requirements into promotion criteria for government officials, and increasing rural incomes to allow domestic demand to play a greater role in driving economic growth. The leadership has also downsized the government bureaucracy.

In the 1980s, China tried to combine central planning with market-oriented reforms to increase productivity, living standards, and technological quality without exacerbating inflation, unemployment, and budget deficits. It pursued agricultural reforms, dismantling the commune system and introducing a household-based system that provided peasants greater decision-making in agricultural activities. The government also encouraged nonagricultural activities such as village enterprises in rural areas, promoted more self-management for state-owned enterprises, increased competition in the marketplace, and facilitated direct contact between Chinese and foreign trading enterprises. China also relied more upon foreign financing and imports.

During the 1980s, these reforms led to average annual growth rates of 10% in agricultural and industrial output. Rural per capita real income doubled. China became self-sufficient in grain production; rural industries accounted for 23% of agricultural output, helping absorb surplus labor in the countryside. The variety of light industrial and consumer goods increased. Reforms began in the fiscal, financial, banking, price-setting, and labor systems.

By the late 1980s, however, the economy had become overheated, with increasing rates of inflation. At the end of 1988, in reaction to a surge of inflation caused by accelerated price reforms, the leadership introduced an austerity program.

China's economy regained momentum in the early 1990s. During a visit to southern China in early 1992, China's paramount leader at the time, Deng Xiaoping, made a series of political pronouncements designed to reinvigorate the process of economic reform. The 14th Party Congress later in the year backed Deng's renewed push for market reforms, stating that China's key task in the 1990s was to create a "socialist market economy." The 10-year development plan for the 1990s stressed continuity in the political system with bolder reform of the economic system.

Following the Chinese Communist Party's October 2003 Third Plenum, Chinese legislators unveiled several proposed amendments to the state constitution. One of the most significant was a proposal to provide protection for private property rights. Legislators also indicated there would be a new emphasis on certain aspects of overall government economic policy, including efforts to reduce unemployment, which was officially 4.1% for urban areas in 2010 but is much higher when migrants are included. Other areas of emphasis include rebalancing income distribution between urban and rural regions and maintaining economic growth while protecting the environment and improving social equity. The National People's Congress approved the amendments when it met in March 2004. The Fifth Plenum in October 2005 approved the 11th Five-Year Plan aimed at building a "harmonious society" through more balanced wealth distribution and improved education, medical care, and social security.

After keeping its currency tightly linked to the US dollar for years, in July 2005 China revalued its currency by 2.1% against the US dollar and moved to an exchange rate system that references a basket of currencies. From mid 2005 to late 2008 cumulative appreciation of the renminbi against the US dollar was more than 20%, but the exchange rate remained virtually pegged to the dollar from the onset of the global financial crisis until June 2010, when Beijing allowed resumption of a gradual appreciation. The restructuring of the economy and resulting efficiency gains have contributed to a more than tenfold increase in GDP since 1978.

Measured on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis that adjusts for price differences, China in 2010 stood as the second-largest economy in the world after the US, having surpassed Japan in 2001. The dollar values of China's agricultural and industrial output each exceed those of the US; China is second to the US in the value of services it produces. Still, per capita income is below the world average. The Chinese government faces numerous economic challenges, including:

(a) reducing its high domestic savings rate and correspondingly low domestic demand;

(b) sustaining adequate job growth for tens of millions of migrants and new entrants to the work force;

(c) reducing corruption and other economic crimes; and

(d) containing environmental damage and social strife related to the economy's rapid transformation.

Economic development has progressed further in coastal provinces than in the interior, and by 2011 more than 250 million migrant workers and their dependents had relocated to urban areas to find work. One consequence of population control policy is that China is now one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world.

Deterioration in the environment - notably air pollution, soil erosion, and the steady fall of the water table, especially in the North - is another long-term problem. China continues to lose arable land because of erosion and economic development. The Chinese government is seeking to add energy production capacity from sources other than coal and oil, focusing on nuclear power and alternative energy development.

In 2010-11, China faced high inflation resulting largely from its credit-fueled stimulus program. Some tightening measures appear to have controlled inflation, but GDP growth consequently slowed to near 9% for 2011. An economic slowdown in Europe is expected to further drag Chinese growth in 2012.

Debt overhang from the stimulus program, particularly among local governments, and a property price bubble challenge policy makers currently.

The 12th Five-Year Plan was debated in mid-October 2010 at the fifth plenary session of the 17th Central Committee of the CCP, and approved by the National People's Congress during its annual session in March 2011. The 12th Five-Year Plan seeks to transform China's development model from one reliant on exports and investment to a model based on domestic consumption. It also seeks to address rising inequality and create an environment for more sustainable growth by prioritizing more equitable wealth distribution, increased domestic consumption, and improved social infrastructure and social safety nets.

GDP: (Purchasing Power Parity): $11.3 trillion (2011 est.)

GDP: (Official Exchange Rate): $6.989 trillion

Note: because China's exchange rate is determine by fiat, rather than by market forces, the official exchange rate measure of GDP is not an accurate measure of China's output; GDP at the official exchange rate substantially understates the actual level of China's output vis-a-vis the rest of the world; in China's situation, GDP at purchasing power parity provides the best measure for comparing output across countries (2011 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP): $8,400 (2011 est.)

GDP- composition by sector:

agriculture: 9.6%

industry: 47.1%

services: 43.3% (2011 est.)

Industries: World leader in gross value of industrial output; mining and ore processing, iron, steel, aluminum, and other metals, coal; machine building; armaments; textiles and apparel; petroleum; cement; chemicals; fertilizers; consumer products, including footwear, toys, and electronics; food processing; transportation equipment, including automobiles, rail cars and locomotives, ships, and aircraft; telecommunications equipment, commercial space launch vehicles, satellites

Currency: Renminbi yuan (RMB)

Industry

Industry accounts for about 46.8% of China's GDP (2010 est.). Major industries are mining and ore processing; iron; steel; aluminum; coal; machinery; textiles and apparel; armaments; petroleum; cement; chemicals; fertilizers; consumer products including footwear, toys, and electronics; automobiles and other transportation equipment including rail cars and locomotives, ships, and aircraft; telecommunications equipment; commercial space launch vehicles; and satellites. China has become a preferred destination for the relocation of global manufacturing facilities. Its strength as an export platform has contributed to incomes and employment in China. The state-owned sector still accounts for about 40% of GDP (2010 est.). In recent years, authorities have been giving greater attention to the management of state assets--both in the financial market as well as among state-owned enterprises--and progress has been noteworthy.

Regulatory Environment

Though China's economy has expanded rapidly, its regulatory environment has not kept pace. Since Deng Xiaoping's open market reforms, the growth of new businesses has outpaced the government's ability to regulate them. This has created a situation where businesses, faced with mounting competition and poor oversight, will be willing to take drastic measures to increase profit margins, often at the expense of consumer safety. This issue acquired more prominence starting in 2007, with the United States placing a number of restrictions on problematic Chinese exports. The Chinese Government recognizes the severity of the problem, concluding in 2007 that nearly 20% of the country's products are substandard or tainted, and is undertaking efforts in coordination with the United States and others to better regulate the problem. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) takes advantage of its presence in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou to monitor food safety issues, and in early 2011 the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission opened its first-ever foreign office in Beijing to enhance cooperation and intensify exchanges with Chinese product safety regulators.

Trade with the United States

The U.S. trade deficit with China rose to $273.1 billion in 2010. This represents almost 55% of the total U.S. trade deficit. While U.S. exports to China grew by a third in 2010 to an all-time high of $91.9 billion, U.S. imports from China increased 23.1% to $364.9 billion. The top three U.S. exports to China in 2010 were electrical machinery ($11.5 billion), nuclear reactors and related machinery ($11.2 billion), and oil seeds and related products ($11 billion).

China remained the third-largest market for U.S. exports, accounting for 7.2% of U.S. goods exports in 2010. U.S. agricultural exports continue to play a major role in bilateral trade, totaling $17.9 billion in 2010 and thus making China the United States' largest agricultural export market. Leading categories include: soybeans ($11.3 billion), cotton ($1.988 billion), and hides and skins ($822 million).

Export growth continues to play an important role in China's rapid economic growth. To increase exports, China pursues policies such as fostering the rapid development of foreign-invested factories, which assemble imported components into consumer goods for export, and liberalizing trading rights. Since the adoption of the 11th Five-Year Program in 2005, however, China has placed greater emphasis on developing a consumer demand-driven economy to sustain economic growth and address global imbalances.

Foreign Investment

China's investment climate has changed dramatically in a quarter-century of reform. In the early 1980s, China restricted foreign investments to export-oriented operations and required foreign investors to form joint-venture partnerships with Chinese firms. Foreign direct investment (FDI) grew quickly during the 1980s, but slowed in late 1989 in the aftermath of Tiananmen. In response, the government introduced legislation and regulations designed to encourage foreigners to invest in high-priority sectors and regions. Since the early 1990s, China has allowed foreign investors to manufacture and sell a wide range of goods on the domestic market and authorized the establishment of wholly foreign-owned enterprises, now the preferred form of FDI. However, the Chinese Government's emphasis on guiding FDI into manufacturing has led to market saturation in some industries, while leaving China's services sectors underdeveloped. China is one of the leading FDI recipients in the world, receiving a record $105.7 billion in 2010 according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce.

As part of its World Trade Organization (WTO) accession, China undertook to eliminate certain trade-related investment measures and to open up specified sectors that had previously been closed to foreign investment. Many new laws, regulations, and administrative measures to implement these commitments have been issued. Despite some reforms, major barriers to foreign investment remain, including restrictions on entire sectors, opaque and inconsistently enforced laws and regulations, and the lack of a rules-based legal infrastructure.

Opening to the outside remains central to China's development. Foreign-invested enterprises produce about half of China's exports, and China continues to attract large investment inflows. Foreign exchange reserves were $2.622 trillion at the end of 2010, and have now surpassed those of Japan, making China's foreign exchange reserves the largest in the world. As a result of its “going out” policy, China's outbound foreign direct investment, especially in energy and natural resources, has also surged in recent years, reaching $59 billion in 2010, up from a yearly average of $2 billion in the 1990s.

See also: Eco-industrial parks in China

Science and Technology

Science and technology have always been a priority for China's leaders. Deng called it "the first productive force." Distortions in the economy and society created by party rule have severely hurt Chinese science, according to some Chinese science policy experts. The Chinese Academy of Sciences, modeled on the Soviet system, puts much of China's greatest scientific talent in a large, underfunded apparatus that remains largely isolated from industry, although the reforms of the past decade have begun to address this problem.

China is making significant investments in science and technology. Chinese science strategists see China's greatest opportunities in fields such as biotechnology and computers, where China is becoming an increasingly significant player. More overseas Chinese students are choosing to return home to work after graduation, and they have built a dense network of trans-Pacific contacts that will greatly facilitate U.S.-China scientific cooperation in coming years. The Chinese Government has increased incentives for students to return, such as salaries similar to those they would receive in the West. The U.S. space program is often held up as the standard of scientific modernity in China. China’s growing space program, which successfully completed its third manned orbit in September 2008, is a focus of national pride. During National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Administrator Charles Bolden’s October 2010 visit to China both sides agreed that transparency, reciprocity, and mutual benefit should serve as the foundation for future dialogue.

The U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement remains the framework for bilateral cooperation in this field. During President Hu’s January 2011 visit, the U.S. and China renewed the science and technology agreement, extending the framework for an additional five years. The agreement is among the longest-standing U.S.-China accords, and includes over 11 U.S. Federal agencies and numerous branches that participate in cooperative exchanges under the science and technology agreement and its nearly 60 protocols, memoranda of understanding, agreements, and annexes. The agreement covers cooperation in areas such as marine conservation, renewable energy, and health. Biennial Joint Commission Meetings on Science and Technology bring together policymakers from both sides to coordinate joint science and technology cooperation. Executive Secretaries meetings are held biennially to implement specific cooperation programs. Japan and the European Union also have high-profile science and technology cooperative relationships with China.

Foreign Relations

Since its establishment, the People's Republic has worked vigorously to win international support for its position that it is the sole legitimate government of all China, including Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Taiwan. In the early 1970s, most world powers diplomatically recognized Beijing. Beijing assumed the China seat in the United Nations (UN) in 1971 and has since become increasingly active in multilateral organizations. Japan established diplomatic relations with China in 1972, and the United States did so in 1979. As of 2011, the number of countries that had diplomatic relations with Beijing had risen to 171, while 23 maintained diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

After the founding of the P.R.C., China's foreign policy initially focused on solidarity with the Soviet Union and other communist countries. In 1950, China sent the People's Liberation Army into North Korea to help North Korea halt the UN offensive that was approaching the Yalu River. After the conclusion of the Korean conflict, China sought to balance its identification as a member of the Soviet bloc by establishing friendly relations with Pakistan and other Third World countries, particularly in Southeast Asia.

In the 1960s, Beijing competed with Moscow for political influence among communist parties and in the developing world generally. Following the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and clashes in 1969 on the Sino-Soviet border, Chinese competition with the Soviet Union increasingly reflected concern over China's own strategic position.

In late 1978, the Chinese also became concerned over Vietnam's efforts to establish open control over Laos and Cambodia. In response to the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, China fought a brief border war with Vietnam (February-March 1979) with the stated purpose of "teaching Vietnam a lesson."

Chinese anxiety about Soviet strategic advances was heightened following the Soviet Union's December 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. Sharp differences between China and the Soviet Union persisted over Soviet support for Vietnam's continued occupation of Cambodia, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and Soviet troops along the Sino-Soviet border and in Mongolia--the so-called "three obstacles" to improved Sino-Soviet relations.

In the 1970s and 1980s China sought to create a secure regional and global environment and to foster good relations with countries that could aid its economic development. To this end, China looked to the West for assistance with its modernization drive and for help in countering Soviet expansionism, which it characterized as the greatest threat to its national security and to world peace.

China maintained its consistent opposition to "superpower hegemony," focusing almost exclusively on the expansionist actions of the Soviet Union and Soviet proxies such as Vietnam and Cuba, but it also placed growing emphasis on a foreign policy independent of both the United States and the Soviet Union. While improving ties with the West, China continued to follow closely economic and other positions of the Third World nonaligned movement, although China was not a formal member.

In the immediate aftermath of Tiananmen crackdown in June 1989, many countries reduced their diplomatic contacts with China as well as their economic assistance programs. In response, China worked vigorously to expand its relations with foreign countries, and by late 1990, had reestablished normal relations with almost all nations. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991, China also opened diplomatic relations with the republics of the former Soviet Union.

In recent years, Chinese leaders have been regular travelers to all parts of the globe, and China has sought a higher profile in the UN through its permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and other multilateral organizations. Closer to home, China has made efforts to reduce tensions in Asia, hosting the Six-Party Talks on North Korea's nuclear weapons program. The United States and China share common goals of peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula and North Korean denuclearization. The U.S. continually consults with China on how it can best use its influence with North Korea and discusses the importance of fully implementing U.N. Security Council Resolutions 1718 and 1874, including sanctions to prevent North Korean proliferation activities.