Global material cycles

Contents

Introduction

The earth is a constant recipient of an enormous flux of solar radiation (Global material cycles) as well as considerable infall of the cosmic debris that also arrives periodically in huge, catastrophe-inducing encounters with other space bodies, particularly with massive comets and asteroids. Nothing else comes in, and the planet's relatively powerful gravity prevents anything substantial from leaving. Consequently, life on the earth is predicated on incessant cycling of water and materials that are needed to assemble living bodies as well as to provide suitable environmental conditions for their evolution. These cycles are energized by two distinct sources: Whereas the water cycle and the circulations of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, the three key life-building elements, are powered by solar radiation, the planet's grand tectonic cycle is driven by the earth's heat. For hundreds of thousands of years, our species had no discernible large-scale effect on these natural processes, but during the 20th century anthropogenic interferences in global biospheric cycles became a matter of scientific concern and an increasingly important, and controversial, topic of public policy debates.

Material Cycles

Two massive material cycles would be taking place even on a lifeless Earth: (i) a slow formation and recycling of the planet's thin crust and (ii) evaporation, condensation, and runoff of water. As weathering breaks down exposed rocks, their constituent minerals are transported by wind in terrigenic dust and in flowing water as ionic solutions or suspended matter. Their journey eventually ends in the ocean, and the deposited materials are either drawn into the mantle to reemerge in new configurations 107–108 years later along the ocean ridges or in volcanic hot spots or they resurface as a result of tectonic movements as new mountain ranges. This grand sedimentary–tectonic sequence recycles not just all trace metals that are indispensable in small amounts for both auto- and heterotrophic metabolism but also phosphorus, one of the three essential plant macronutrients.

On human timescale (101 years), we can directly observe only a minuscule segment of the geotectonic weathering cycle and measure its rates mostly as one-way ocean-ward fluxes of water-borne compounds. Human actions are of no consequence as far as the geotectonic processes are concerned, but they have greatly accelerated the rate of weathering due to deforestation, overgrazing of pastures, and improper crop cultivation. Incredibly, the annual rate of this unintended earth movement, 50–80 billion metric tons (Gt), is now considerably higher than the aggregate rate of global weathering before the rise of agriculture (no more than 30 Gt/year).

In addition, we act as intentional geomorphic agents as we extract, displace, and process crustal minerals, mostly sand, stone, and fossil fuels. The aggregate mass moved annually by these activities is also larger than the natural preagricultural weathering rate. Our activities have also profoundly affected both the quantity and the quality of water cycled on local and regional scales, but they cannot directly change the global water flux driven predominantly by the evaporation from the ocean. However, a major consequence of a rapid anthropogenic global warming would be an eventual intensification of the water cycle.

In contrast to these two solely, or overwhelmingly, inanimate cycles, global circulations of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur are to a large extent driven or mediated by living organisms, largely by bacteria, archaea, and plants. Another characteristic that these cycles have in common is their relatively modest claim on the planet's energy flows. Photosynthesis, carbon (Carbon cycle) cycle's key terrestrial flux, requires only a tiny share of incident solar radiation, and the cycling of nitrogen and sulfur involves much smaller masses of materials and hence these two cycles need even less energy for their operation: Their indispensability for Earth's life is in renewing the availability of elements that impart specific qualities to living molecules rather than in moving large quantities of materials. Similarly, only a small fraction of the planet's geothermal heat is needed to power the processes of global geotectonics.

Although the basic energetics of all these cycles is fairly well-known, numerous particulars remain elusive, including not only specific details, whose elaboration would not change the fundamental understanding of how these cycles operate, but also major uncertainties regarding the extent and consequences of human interference in the flows of the three doubly mobile elements (carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur), whose compounds are transported while dissolved in water as well as relatively long-lived atmospheric gases. For millennia these interventions were discernible only on local and regional scales, but during the 20th century their impacts increased to such an extent that the effects of these interferences now present some historically unprecedented challenges even in global terms.

Geotectonic Cycle

The earth's surface is composed of rigid oceanic and continental plates. The former are relatively thin (mostly 5–7 kilometers [km]), short-lived (mostly less than 140 million years [Ma]), and highly mobile (up to 10–20 cm/year). The latter ones are thicker (only 35–40 km), long-lived (109 years), and some, most notably Asian and African plates, are virtually stationary. Plates ride on the nearly 3000-km-thick solid but flowing mantle, which is the source of hot magma whose outpourings create new seafloor along approximately 72,000 km of the earth-encircling ocean ridge system. Old seafloor is eventually recycled back into the mantle in subduction zones marked by deep ocean trenches (Fig. 1). There are substantial uncertainties concerning the actual movements of the subducted plates within the mantle: The principal debate is between the two-layer models and the whole-mantle flows.

Today's oceans and continents are thus transitory features produced by incessant geotectonic processes that are energized by three sources of the earth's heat: energy conducted through the lithosphere from the underlying hot mantle, radiogenic decay of heat-producing crustal elements, and convective transport by magmas and fluids during orogenic events. The relative importance of these heat sources remains in dispute, but the heat flow at the earth's surface can be measured with high accuracy. Its total is approximately 44 trillion watts (TW), prorating to approximately 85 mW/m2 of the earth's surface. The average global heat flux of approximately 85 mW/m2 is equal to a mere 0.05% of solar radiation absorbed by surfaces (168 W/m2), but acting over huge areas and across long timespans, this flow is responsible not only for creating new ocean floor, reshaping continents, and building enormous mountain chains but also for energizing earthquakes and [[volcanic] eruptions].

Mean oceanic heat flow is approximately 100 mW/m2, whereas the continental flow is only approximately half as high. The ocean floor transmits approximately 70% of the earth's total geothermal flux and nearly one-third of the oceanic heat loss occurs in the South Pacific, where the spreading rates, particularly along the Nazca Ridge, are faster than anywhere else on Earth. By far the highest heat flows are along mid-ocean ridges, where approximately 3–3.5 km2 of new ocean floor is created by hot magma rising from the mantle. The total heat flux at the ridges, composed of the latent heat of crystallization of newly formed ocean crust and of the heat of cooling from magmatic temperatures (approximately 1200 °C) to hydrothermal temperatures (approximately 350 °C), is between 2 and 4 TW.

Divergent spreading of oceanic plates eventually ends at subduction zones, where the crust and the uppermost part of the mantle are recycled deep into the mantle to reappear through igneous process along the ridges. Every new cycle begins with the breakup of a supercontinent, a process that typically takes approximately 200 Ma, and is followed first by slab avalanches and then by rising mantle plumes that produce juvenile crust. After 200–440 Ma, the new supercontinent is broken up by mantle upwelling beneath it.

During the past billion years (Ga), the earth has experienced the formation and breakup of three supercontinents: Rodinia (formed 1.32–1.0 Ga ago and broken up between 700 and 530 Ma ago), Gondwana (formed between 650 and 550 Ma ago), and Pangea (formed 450–250 Ma ago and began to break up approximately 160 Ma ago). Pangea spanned the planet latitudinally, from today's high Arctic to Antarctica; its eastern flank was notched by a V-shaped Tethys Sea centered approximately on the equator. Unmistakable signs of continental rifting can be seen today underneath the Red Sea and along the Great Rift Valley of East Africa: The process of continental breakup is still very much under way.

Inevitably, these grand geotectonic cycles had an enormous impact on the evolution of life. They made it possible to keep a significant share of the earth's surface above the sea during the past 3 Ga, allowing for the evolution of all complex terrestrial forms of life. Changing locations and distributions of continents and oceans create different patterns of global oceanic and atmospheric circulation, the two key determinants of climate. Emergence and diversification of land plants and terrestrial fauna during the past 500 Ma years have been much influenced by changing locations and sizes of the continents. The surface we inhabit today has been, to a large extent, fashioned by the still continuing breakup of Pangea. Two of the earth's massive land features that have determined the climate for nearly half of humanity—the Himalayas, the world's tallest mountain chain, and the high Tibetan Plateau—are its direct consequences. So is the northward flow of warm Atlantic waters carried by the Gulf Stream that helps to create the mild climate in Western Europe. Volcanic eruptions have been the most important natural source of CO2 and, hence, a key variable in the long-term balance of the biospheric carbon. Intermittently, they are an enormous source of aerosols, whose high atmospheric concentrations have major global climatic impacts.

Water Cycle

Most of the living biomass is water, and this unique triatomic compound is also indispensable for all metabolic processes. The water molecule is too heavy to escape the earth's gravity, and juvenile water, originating in deeper layers of the crust, adds only a negligible amount to the compound's biospheric cycle. Additions due to human activities—mainly withdrawals from ancient aquifers, some chemical syntheses, and combustion of fossil fuels—are also negligible. Both the total volume of Earth's water and its division among the major reservoirs can thus be considered constant on a timescale of 103 years. On longer timescales, glacial–interglacial oscillations shift enormous volumes of water among oceans and glaciers and permanent snow.

The global water cycle is energized primarily by evaporation from the ocean (Fig. 2). The ocean covers 70% of the earth, it stores 96.5% of the earth's water, and it is the source of approximately 86% of all evaporation. Water has many extraordinary properties. A very high specific heat and heat capacity make it particularly suitable to be the medium of global temperature regulation. High heat of vaporization (approximately 2.45 kilojoules per gram [kJ/g]) makes it an ideal transporter of latent heat and helps to retain plant and soil moisture in hot environments. Vaporization of 1 millimeter per day (mm/day) requires 28 or 29 watts per square meter (W/m2), and with average daily evaporation of approximately 3 mm, or an annual total of 1.1 m, the global latent heat flux averages approximately 90 W/m2. This means that approximately 45 quadrillion watts (PW), or slightly more than one-third of the solar energy absorbed by the earth's surface and the planet's atmosphere (but 4000 times the amount of annual commercial energy uses), is needed to drive the global water cycle.

The global pattern of evaporation is determined not only by the intensity of insolation but also by the ocean's overturning circulation as cold, dense water sinks near the poles and is replaced by the flow from low latitudes. There are two nearly independent overturning cells—one connects the Atlantic Ocean to other basins through the Southern Ocean, and the other links the Indian and Pacific basins through the Indonesian archipelago. Measurements taken as a part of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment show that 1.3 PW of heat flows between the subtropical (latitude of southern Florida) and the North Atlantic, virtually the same flux as that observed between the Pacific and Indian Oceans through the Indonesian straits.

Poleward heat transfer of latent heat also includes some of the most violent low-pressure cells (cyclones), American hurricanes, and Asian typhoons. Oceanic evaporation (heating of equatorial waters) is also responsible for the Asian monsoon, the planet's most spectacular way of shifting the heat absorbed by warm tropical oceans to continents. The Asian monsoon (influencing marginally also parts of Africa) affects approximately half of the world's population, and it precipitates approximately 90% of water evaporated from the ocean back onto the sea. Evaporation exceeds precipitation in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, the reverse is true in the Arctic Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean flows are nearly balanced.

Because of irregular patterns of oceanic evaporation (maxima up to 3 m/year) and precipitation (maxima up to 5 m/year), large compensating flows are needed to maintain sea level. The North Pacific is the largest surplus region (and hence its water (Seawater) is less salty), whereas evaporation dominates in the Atlantic. In the long term, oceanic evaporation is determined by the mean sea level. During the last glacial maximum 18,000 years ago, the level was 85–130 m lower than it is now, and satellite measurements indicate a recent global mean sea level rise of approximately 4 mm per year.

The difference between precipitation of evapotranspiration has a clear equatorial peak that is associated with convective cloud systems, whereas the secondary maxima (near 50°N and °S) are the result of extratropical cyclones and midlatitude convection. Regarding the rain on land, approximately one-third of it comes from ocean-derived water vapor, with the rest originating from evaporation from non-vegetated surfaces and from evapotranspiration (evaporation through stomata of leaves). Approximately 60% of all land precipitation is evaporated, 10% goes back to the ocean as surface runoff, and approximately 30% is carried by rivers (Fig. 2). Because the mean continental elevation is approximately 850 m, this river-borne flux implies an annual conversion of approximately 370×1018 J of potential energy to kinetic energy of flowing water, the principal agent of geomorphic denudation shaping the earth's surfaces. No more than approximately 15% of the flowing water's aggregate potential energy is convertible to hydroelectricity.

The closing arm of the global water cycle works rather rapidly because average residence times of freshwater range from just 2 weeks in river channels to weeks to months in [[soil]s]. However, widespread construction of dams means that in some river basins water that reaches the sea is more than 1 year old. In contrast to the normally rapid surface runoff, water may spend many thousands of years in deep aquifers. Perhaps as much as two-thirds of all freshwater on Earth is contained in underground reservoirs, and they annually cycle the equivalent of approximately 30% of the total runoff to maintain stable river flows. Submarine groundwater discharge, the direct flow of water into the sea through porous rocks and sediments, appears to be a much larger flux of the global water cycle than previously estimated.

Carbon Cycle

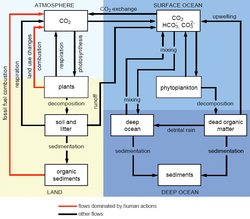

The key structural element of life keeps cycling on several spatial and temporal scales, ranging from virtually instantaneous returns to circulations that take 108 years to complete. At one extreme are very rapid assimilation–respiration flows between the plants and the atmosphere and less rapid but still fast assimilation–decomposition–assimilation circuits that move the element from the atmosphere to plant tissue of various ecosystems and return it to the atmosphere after [[carbon]'s] temporary stores in dead organic matter (in surface litter and [[soil]s]) are mineralized by decomposers (Fig. 3). The other extreme involves slow weathering of terrestrial carbonates, their dissolution, river-borne transport, and eventual sedimentation in the ocean, and the element's return to land by geotectonic processes. Human interest in the cycle is due not only to the fact that carbon's assimilation through photosynthesis is the foundation of all but a tiny fraction of the earth's life but also to the cycle's sensitivity to anthropogenic perturbations.

Photosynthesis, the dominant biospheric conversion of inorganic carbon from the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) to a huge array of complex organic molecules in plants, proceeds with very low efficiency. On average, only approximately 0.3% of the electromagnetic energy of solar radiation that reaches the earth's ice-free surfaces is converted to chemical energy of new phytomass. Short-term maxima in the most productive crop fields can be close to 5%, whereas even the tropical rain forests, the planet's most productive natural ecosystems, do not average more than 1%. Plant (autotrophic) respiration consumes approximately half of the gross photosynthesis, and it reduces the global net primary productivity (i.e., the new phytomass available every year for consumption by heterotrophs [from bacteria to humans]) to approximately 60 Gt of carbon on land and approximately 50 Gt of carbon in the ocean.

Virtually all this fixed carbon is eventually returned to the atmosphere through heterotrophic respiration, and only a tiny fraction that accumulates in terrestrial sediments forms the bridge between the element's rapid and slow cycles. After 106–108 years of exposure to high pressures and temperatures, these sediments are converted to fossil fuels. The most likely global total of biomass carbon that was transformed into the crustal resources of coals and hydrocarbons is in excess of 5 Tt of oil equivalent, or 2.1×1023 J. However, some hydrocarbons, particularly natural gas, may be of abiotic origin. Much more of the ancient organic carbon is sequestered in kerogens, which are transformed remains of buried biomass found mostly in calcareous and oil shales.

Intermediate and deep waters contain approximately 98% of the ocean's huge carbon stores, and they have a relatively large capacity to sequester more CO2 from the atmosphere. The exchange of CO2 between the atmosphere and the ocean's topmost (mixed) layer helps to keep these two carbon reservoirs stable. This equilibrium can be disrupted by massive CO2-rich volcanic eruptions or abrupt climate changes. However, the rate of CO2 exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean is limited because of the slow interchange between the relatively warm mixed layer (>25°C in the tropics) and cold (2–4 °C) deep waters. As is the case on land, only a small fraction of organic carbon is not respired and goes into ocean sediments (Fig. 3).

Analysis of air bubbles from polar ice cores shows that the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has remained between 180 and 300 parts per million (ppm) during the past 420,000 years and 250–290 ppm since the rise of the first high civilizations during the 5000 years preceding the mid-19th century. Humans began changing this relatively stable state of affairs first by clearing natural vegetation for fields and settlements, but until the 19th century these releases of CO2 did not make any marked difference. These conversions became much more extensive after 1850, coinciding with the emergence of fossil-fueled civilization.

Land use changes dominated the anthropogenic mobilization of carbon until the beginning of the 20th century and they are now the source of 1.5–2 Gt of carbon per year to the atmosphere. Fossil fuel combustion had accelerated from an annual conversion of 22 exajoules (EJ) and emissions of less than 0.5 Gt of carbon in 1900 to more than 300 EJ and releases of more than 6 Gt of carbon by 2000. Every year, on average, approximately half of this anthropogenic flux of approximately 8 Gt of carbon stays in the atmosphere. As a result, atmospheric CO2 levels that have been constantly monitored at Hawaii's Mauna Loa observatory since 1958 increased from 320 ppm during the first year of measurement to 370 ppm in 2000.

A nearly 40% increase in 150 years is of concern because CO2 is a major greenhouse gas whose main absorption band of the outgoing radiation coincides with Earth's peak thermal emission. A greenhouse effect is necessary to maintain the average surface temperature approximately 33 °C above the level that would result from an unimpeded reradiation of the absorbed insolation, and energy reradiated by the atmosphere is currently approximately 325 W/m2. During the past 150 years, anthropogenic CO2 has increased this flux by 1.5 W/m2 and other greenhouse gases have added approximately 1 W/m2.

The expected temperature increase caused by this forcing has been partially counteracted by the presence of anthropogenic sulfur compounds in the atmosphere, but another century of massive fossil fuel combustion could double the current CO2 levels and result in rapid global warming. Its effects would be more pronounced in higher latitudes, and they would include intensification of the global water cycle that would be accompanied by unevenly distributed changes in precipitation patterns and by thermal expansion of seawater leading to a gradual rise in sea level.

Nitrogen Cycle

Although carbon is the most important constituent of all living matter (making up, on average, approximately 45% of dry mass), cellulose and lignin, the two dominant molecules of terrestrial life, contain no nitrogen. Only plant seeds and lean animal tissues have high protein content (mostly between 10 and 25%; soybeans up to 40%), and although nitrogen is an indispensable ingredient of all enzymes, its total reservoir in living matter is less than 2% of carbon's huge stores. Unlike the cycles of water or carbon (Carbon cycle) that include large flows entirely or largely unconnected to biota, every major link in nitrogen's biospheric cycle is mediated by bacteria.

Nitrogen fixation—a severing of the element's highly stable and chemically inert molecule (N2) that makes up 78% of the atmosphere and its incorporation into reactive ammonia—launches this great cascade of biogenic transformations. Only a very limited number of organisms that possess nitrogenase, the enzyme able to cleave N2 at ambient temperature and at normal pressure, can perform this conversion. Several genera of rhizobial bacteria live symbiotically with leguminous plants and are by far the most important fixers of nitrogen on land, whereas cyanobacteria dominate the process in fresh (Freshwater biomes)waters as well as in the ocean.

There are also endophytic symbionts (bacteria living inside stems and leaves) and free-living bacterial fixers in [[soil]s]. The current annual rate of biofixation in terrestrial ecosystems is no less than 160 million metric tons (Mt) of nitrogen, and at least 30 Mt of nitrogen is fixed in crop fields. Biofixation is a relatively energy-intensive process, with 6–12 g of carbon (delivered by the plant to bacteria as sugar) needed for every gram of fixed nitrogen. This means that the terrestrial biofixation of approximately 200 Mt of nitrogen requires at least 1.2 Gt of carbon per year, but this is still no more than 2% of the net terrestrial primary productivity.

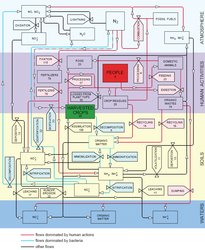

Subsequently, there are four key links in the nitrogen cycle (Fig. 4). After nitrogen fixation is nitrification, the conversion of ammonia to more water-soluble nitrates, which is performed by a small number of bacterial species living in both soils and water. Assimilation is the incorporation of reactive nitrogen, be it as ammonia (NH3) or as nitrate (NO?3), by autotrophic organisms into amino acids that are then used to synthesize proteins. Ammonification is enzymatic decomposition of organic matter performed by many prokaryotes that produces ammonia for nitrification. Finally, denitrification is the closing arm of the cycle in which bacteria convert nitrates into nitrites and then into N2.

Human interference in the nitrogen cycle is largely due to the fact that heterotrophs, including people, cannot synthesize their own amino acids and hence must digest preformed proteins. Because nitrogen is the most common yield-limiting nutrient in crop cultivation, all traditional [[agriculture]s] had to resort to widespread planting of leguminous crops and to diligent recycling of nitrogen-rich organic wastes. However, the extent of these practices is clearly limited by the need to grow higher yielding cereals and by the availability of crop residues and human and animal wastes. Only the invention of ammonia synthesis from its elements by Fritz Haber in 1909 and an unusually rapid commercialization of this process by the BASF company under the leadership of Carl Bosch (by 1913) removed the nitrogen limit on crop production and allowed for the expansion of the human population supplied by adequate nutrition (both chemists were later awarded Nobel Prizes for their work). Currently, malnutrition is a matter of distribution and access to food, not of its shortage.

These advances have a considerable energy cost. Despite impressive efficiency gains, particularly since the early 1960s, NH3 synthesis requires, on average, more than 40 GJ/t, and the conversion of the compound to urea, the dominant nitrogen fertilizer, raises the energy cost to approximately 60 GJ/t of nitrogen. In 2000, Haber-Bosch synthesis produced approximately 130 Mt of NH3 (or 110 Mt of nitrogen). With production and transportation losses of approximately 10%, and with 15% destined for industrial uses, approximately 82 Mt of nitrogen was used as fertilizer at an aggregate embodied cost of approximately 5 EJ, or roughly 1.5% of the world's commercial supply of primary energy.

The third most important human interference in the global nitrogen cycle (besides NH3 synthesis and planting of legumes) is the high-temperature combustion of fossil fuels, which released more than 30 Mt of nitrogen, mostly as nitrogen oxides (NOx), in 2000. Conversion of these oxides to nitrates, leaching of nitrates, and volatilization of ammonia from fertilized fields (only approximately half of the nutrient is actually assimilated by crops) and from animal wastes are the principal sources of nitrogen leakage into ecosystems. Excess nitrogen causes eutrophication of fresh (Freshwater biomes) and coastal waters, and it raises concerns about the long-term effects on biodiversity and productivity of grasslands and forests. NOx are key precursors of photochemical smog, and rain-deposited nitrates contribute to acidification of waters and [[soil]s]. Nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, released during imperfect denitrification is another long-term environmental concern.

Sulfur Cycle

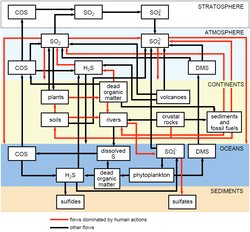

Sulfur is an even rarer component of living molecules than is nitrogen. Only 2 of the 20 amino acids that make up proteins (methionine and cysteine) have the element as part of their molecules, but every protein needs disulfide bridges to make long three-dimensional polypeptide chains whose complex folds allow proteins to be engaged in countless biochemical reactions. The largest natural flux of the element is also the most ephemeral: Sea spray annually carries 140–180 Mt of sulfur into the atmosphere, but 90% of this mass is promptly redeposited in the ocean. Some volcanic eruptions are very large sources of SO2, whereas others have sulfur-poor veils; a long-term average works out to approximately 20 Mt of sulfur per year, and dust, mainly desert gypsum, may contribute the same amount (Fig. 5).

Biogenic sulfur flows may be as low as 15 Mt and as high as 40 Mt of sulfur per year, and they are produced on land by both sulfur-oxidizing and sulfate-reducing bacteria present in water, mud, and hot springs. Emitted gases are dominated by hydrogen sulfide, dimethyl sulfide (DMS), propyl sulfide, and methyl mercaptan. DMS is also generated in relatively large amounts by the decomposition of algal methionine in the ocean, and these emissions have been suggested to act as homeostatic controllers of the earth's climate. Higher concentrations of DMS would increase albedo by providing more condensation nuclei for increased [[cloud]iness], the resulting reduced insolation would lower planktonic photosynthesis, and diminished DMS emissions would provide fewer condensation nuclei and let in more solar radiation. Later studies showed that not just the magnitude but also the very direction of this feedback are questionable.

Human intensification of the sulfur cycle is due largely to the combustion of coals (containing typically approximately 2% sulfur) and crude oils (sweet crudes have less than 0.5% and sour ones more than 2% sulfur). Some natural gases are high in sulfur, containing it mainly as hydrogen sulfide (H2S), but it is easily removed before they enter pipelines. Fossil fuel combustion accounts for more than 90% of all anthropogenic sulfur emissions, whose global total increased from 5 Mt in 1900 to approximately 80 Mt in 2000. The remainder is emitted largely during the smelting of color metals (mainly Cu, Zn, and Pb), and a small share originates in chemical syntheses.

Our interest in the sulfur cycle is mainly due to the fact that sulfur dioxide (SO2) emitted from fossil fuel combustion and nonferrous metallurgy is rapidly oxidized to sulfates, whose deposition is the leading source of acid deposition, both in dry and in wet forms. Before their deposition, sulfur compounds remain up to 3 or 4 days in the lowermost troposphere (average, <40 h), which means that they can travel several hundred to more than 1000 km and bring acid deposition to distant ecosystems. Indeed, the phenomenon was first discovered when SO2 emissions from central Europe began to affect lake biota in southern Scandinavia. Because of the limits on long-distance transport (atmospheric residence times of DMS and H2S are also short-lived), sulfur does not have a true global cycle as does carbon (via CO2) or nitrogen (via denitrification), and the effects of significant acid deposition are limited to large [[region]s] or to semicontinental areas.

Deposited sulfates (and nitrates) have the greatest impact on aquatic ecosystems, especially on lakes with low or no buffering capacity, leading to the decline and then the demise of sensitive fish, amphibians, and invertebrates and eventually to profound changes in a lake's biodiversity. Leaching of alkaline elements and mobilization of toxic aluminum from forest [[soil]s] is another widespread problem in acidified areas, but acid deposition is not the sole, or the principal, cause of reduced forest productivity. Since the early 1980s, concerns about the potential long-term effects of acidification have led to highly successful efforts to reduce anthropogenic SO2 emissions throughout Europe and in eastern North America.

Reductions of sulfur emissions have been achieved by switching to low-sulfur fuels and by desulfurizing fuels and flue gases. Desulfurization of oils, although routine, is costly, and removing organic sulfur from coal is very difficult (pyritic sulfur is much easier to remove). Consequently, the best control strategy for coal sulfur is flue gas desulfurization (FGD) carried out by reacting SO2 with wet or dry basic compounds (CaO and CaCO3). FGD is effective, removing 70–90% of all sulfur, but the average U.S. cost of $125/kW adds at least 10–15% to the original capital expense, and operating the units increases the cost of electricity production by a similar amount. Moreover, FGD generates large volumes of wastes for disposal (mostly CaSO4).

Airborne sulfates also play a relatively major role in the radiation balance of the earth because they partially counteract the effect of [[greenhouse gas]es] by cooling the troposphere: The global average of the aggregate forcing by all sulfur emissions is approximately ?0.6 W/m2. The effect is unevenly distributed, with pronounced peaks in eastern North America, Europe, and East Asia, the three [[region]s] with the highest sulfate levels.

A 16-fold increase in the world's commercial energy consumption that took place during the 20th century resulted in the unprecedented level of human interference in global biochemical cycles. Thus, we must seriously consider the novel and a very sobering possibility that the future limits on human acquisition and conversion of energy may arise from the necessity to keep these cycles compatible with the long-term habitability of the biosphere rather than from any shortages of available energy resources.

Cycles of Mineral Elements

Transfers of mineral elements from continental rocks to the ocean and their eventual resurfacing are part of the grand and ponderous sedimentary-tectonic cycle. This process begins with weathering, a combination of physical and chemical processes that is in many places also strongly affected by vegetation. Silicate weathering releases dissolved silica (SiO2), Ca2+, Na+, K+ and Mg+, dissolution of carbonates yields Ca2+ and bicarbonate (HCO3-) ions, and sulfide weathering produces H2SO4 that causes additional silicate weathering. Average continental weathering rate is less than 0.1 mm/year but the highest rates are up to10 mm in parts of the Himalayas. Weathered material is removed by water runoff (Surface runoff of water), ice and wind erosion. Most of the eroded material is temporarily deposited in river valleys and lowlands. Human activities have at least doubled the global rate of soil erosion, above all due to deforestation and careless crop cultivation, but in many [[region]s] the construction of dams during the 20th century actually reduced the transport of sediments to the ocean. Estimates of sediment transport in the world's rivers are around 20 Gt/year, glacial transport (difficult to estimate) may be as low as 1-2 Gt/year, and wind erosion carries contributes no more than 1 Gt/year. The total annual rate is on the order of 25 Gt, or less than 200 g/m2 of the Earth's surface. The largest elemental constituents of this flux are silicon, iron and calcium.

Annual sedimentation of 25 Gt would denude the continents to the sea level in less than 15 million years but [[tectonic] processes] return the materials to the Earth's surfaces. Marine sediments reemerge either still unconsolidated or after dehydration, lithification and metamorphosis; they can be reexposed by coastline regression or by tectonic uplift during a new mountain-building period, or they can be carried by a subducting oceanic plate deeper into the mantle where they are reconstituted into new igneous rocks an extruded along mid-ocean ridges or in magmatic hot spots. A typical supercontinental cycle takes on the order of 108 years to complete. Three mineral elements deserve a closer attention: phosphorus because of its fundamental role in metabolism and because of its frequently limiting role in plant growth; and calcium and silicon because of their relatively large uptakes by living organisms.

Phosphorus Cycle

Unlike C, N and S, phosphorus (P) does not form any long-lived atmospheric compounds and hence its global cycle is just a part of the grand, and slow, process of denudation and geotectonic uplift. But on a small scale the element is rapidly recycled between organic and inorganic forms in [[soil]s] and water bodies. Human actions are now mobilizing annually more than four times as much P as did the natural processes during the preagricultural era. Phosphorus is absent in the polymers that make up bulk of the plant mass (cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin) as well as in proteins, but it is abundant (as hydroxyapatite) in bones and teeth. The element is indispensable in phosphodiester bonds linking mononucleotide units of RNA and DNA, and all life processes are energized by transformations of adenosine triphosphate. Phosphorus is one of the three macronutrients required by plants; it is particularly important for the growth of young tissues, flowering and seed formation. The element is also an essential micronutrient in humans.

The Earth's crust is the largest reservoir of the element, nearly all of it bound in apatites, calcium phosphates containing also iron, chlorine or OH group. Soluble phosphates are released by weathering, but they are rapidly transformed to insoluble compounds in soils. Consequently, plants must be able to absorb phosphorus from very dilute solutions and concentrate it hundred- to thousand-fold in order to meet their needs, and P released by decomposition of biomass must be rapidly reused. The element is even less available in fresh waters and in the ocean where its particulate forms sink into sediments and where soluble phosphates are rapidly recycled in order to support phytoplanktonic photosynthesis in surface waters. Only in the areas of upwelling are the surface layers enriched by the influx from deeper waters. Phosphorus in marine sediments can become available to terrestrial biota only after the tectonic uplift reexposes the minerals to denudation; the element's global cycle thus closes only after tens to hundreds of millions of years.

Terrestrial phytomass stores about 500 Mt P and plant growth assimilates up to 100 Mt P/year. Phosphates dissolved in rain and dry-deposited in particles amount to only about 3 Mt a year. Soils store about 40 Gt P, with no more than 15% of this total bound in organic matter. Natural denudation and precipitation transfer annually about 10 Mt of particulate and dissolved P from land to the ocean. Marine phytomass stores only some 75 Mt P but because of its rapid turnover it absorbs annually about 1 Gt P from surface water. Mixing between sediments and surface layer is effective only in very shallow waters, and near-surface concentration of the nutrient are high only in coastal areas receiving P-rich runoff.

Human intensification of biospheric P flows is due to accelerated erosion and runoff caused by large-scale conversion of natural ecosystems to arable land, settlements and transportation links; recycling of organic wastes to fields; releases of untreated, or insufficiently treated, urban and industrial wastes to streams and water bodies; applications of inorganic [[fertilizer]s]; and combustion of biomass and fossil fuels. The global population of nearly 7 billion people now discharges every year more than 3 Mt P in its wastes. A large share of human waste produced in rural areas of low-income countries is deposited on land, but progressing urbanization puts a growing share of human waste into sewers and then into streams or water bodies. During the 1940s P-containing detergents became another major source of waterborne P. Neither the primary sedimentation of urban sewage (which removes only 5-10% of P), nor the use of trickling filters during the secondary treatment (removing 10-20% P) prevent eutrophication, undesirable enrichment of waters with the nutrient that most often limits the growth of phytoplankton.

Production of inorganic fertilizers began during the 1840s with the treatment of P-containing rocks with dilute sulfuric acid. The resulting ordinary superphosphate (OSP) contains 7-10% P, ten times as much as recycled P-rich manures. Discovery of huge phosphate deposits in Florida (1870s), Morocco (1910s) and Russia (1930s) laid foundations for the rapid post-WWII expansion of fertilizer industry. Global consumption of phosphatic fertilizers was about 16 Mt P/year in 2006. The top three producers (USA, China and Morocco) now account for about 2/3 of the global output. Crops receiving the highest applications are the US Corn Belt corn (around 60 kg P/ha), Japanese rice (over 40 kg P/ha) and Chinese and West European winter wheat (more than 30 kg P/ha).

Phosphorus applied in both organic and inorganic [[fertilizer]s] is involved in complex reactions which transform a large part of soluble phosphates into much less soluble compounds. This process of P fixation has been known since 1850 and for more than 100 years it was seen as rapid, dominant and irreversible. This misconception resulted in decades of excessive use of P in cropping. Mounting evidence of relatively high efficiency with which crops use the nutrient had finally changed that wasteful practice during the closing decades of the 20th century. Leaching into ground waters and the runoff from fertilizers and manures and sewage discharges enrich surface waters with P. Because a single atom of P supports the production of as much phytomass as 16 atoms of N and 106 atoms of C, even relatively low additions of the nutrient can cause eutrophication of lakes, streams and shallow waters. Just 10 g P/L will support algal growth that will greatly reduce water's clarity, and concentrations above 50 g P/L cause deoxygenation of bottom waters during the decomposition of the accumulated biomass and may result in extensive summer fish kills.

By far the most effective measure to moderate the human impact on P cycle would be to reduce the intake of animal foods: because more than 60% of all P [[fertilizer]s] are used on cereals, and because more than 60% of all grains in rich countries are used as animal feed the need for P fertilizers would decline appreciably. Good agronomic practices can reduce P applications and limit the post-application losses. Phosphorus in sewage can be effectively controlled either by the use of coagulating agents or by microbial processes. Lake eutrophication has been greatly reduced due to the elimination or restricted use of P-based detergents and increased P removal from sewage.

Calcium Cycle

Calcium (Ca) in living organisms is important for both structural and functional reasons. As noted in the P section, hydroxyapatite dominates the biomass of bones and teeth, and innumerable aquatic invertebrates, protists and autotrophs are supported by structures of precipitated CaCO3, while both reptiles and birds use it to form their eggs. Calcium is indispensable for the excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscles and heart, in neurotransmission, intracellular signaling and in mitotic cell division. Long-term cycling of the element is closely coupled with the slow [[carbon (Carbon cycle)] cycle]. Substantial amounts of crustal Ca are locked in apatites and in gypsum (CaSO4, produced by evaporation in shallow waters in arid [[region]s]), but the element's largest sedimentary repository is CaCO3 forming limestones, and dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) making up the bulk of dolostones. Total mass of limestones is on the order of 350 Pt, and an easy solubility of carbonates in slightly acidic precipitation makes Ca2+ one of the most abundant cations in river water.

Deposition of carbonates can take place only in continental shelves and in the shallower parts of the deep ocean because deeper layers—below the carbonate compensation depth which is about 5000 [[meter]s] (m) at the equator, close to 3000 m in high latitudes—are so undersaturated with the respect to the compound that it cannot accumulate. Most inorganically precipitated carbonates have been thus laid down in shallow waters—as must have been the case with biomineralized Ca whose producers are either photosynthesizers or they feed on these autotrophs. In the early lifeless ocean, or in waters containing just prokaryotic organisms, formation of carbonates could proceed only after the two constituent ions reached critical concentrations in the seawater.

Only the emergence of marine biomineralizers using dissolved CaCO3 to make calcite or aragonite shells (differing only in crystal structure), had greatly accelerated the rate of Ca sedimentation. Reef-building corals are certainly the most spectacular communal biomineralizers, but coccolithophorids, golden motile algae which surround themselves with intricate disclike calcitic microstructures, and foraminiferal tests (pore-studded micro shells of protists) are the main contributors to the rain of dead CaCO3 shells on the sea floor. Molluscs, often intricately shaped and patterned, are only minor contributors. Where the detritus rain is heavy the remains of organisms can be quickly buried to form Ca deposits below the carbonate compensation depth (CCD). Eventual return of Ca to subaerial weathering through tectonic uplift is abundantly demonstrated by extensive, and often very thick, layers of limestone and dolomite encountered in all of the world's major mountain ranges.

Silicon Cycle

With about 27% silicon (Si) is—in its various oxidized forms, mostly as silica (SiO2, pure sand) and various silicate minerals—the second most abundant element (after oxygen) in the Earth's crust. Although its is not usually listed as an essential micronutrient, it is absorbed from soil (largely as Si(OH)4) in amounts that surpass several-fold the quantities of other minerals, and that may even be on par with the uptakes of macronutrients (in order to stiffen its stems and leaves rice uses as roughly as much Si as N). Terrestrial plants take up annually nearly 500 Mt of the element. Silicon is transported to the ocean mostly in suspended sediments and it is dissolved in the sea water predominantly as a monomeric silicic acid (Si(OH)4). Its levels are very low in surface waters of central ocean gyres, high in bottom layers almost everywhere. Dissolved silicon is taken up by diatoms, silicoflagellates, radiolarians and other marine organisms in order to form their intricate opal (hydrated, amorphous biogenic silica, SiO2~0.4H2O) structures. This uptake adds up to about 7 Gt/year. The element returns to the solution after the death of aquatic organisms and roughly half of it is rather rapidly recycled within the mixed surface layer. The remainder sinks to deeper layers but most of it is returned to the mixed layer by the process of upwelling. Marine sediments of biogenic silicon are equivalent to less than 3% of the annual uptake by biota, and after their burial they are rapidly recrystallized, primarily as chert.

Reasons for Concern

Natural catastrophes and gradual climatic and geomorphic changes have always had a major influence on the functioning of global material cycles but modern civilization has made some of these interferences both more extensive and more rapid. Changes during the 20th century were more intensive than the cumulative alterations during the preceding five millennia since the emergence of the first settled agricultural societies. They were driven by a nearly 20-fold increase in the world economic product, an achievement that was powered by a 16-fold increase in the world's commercial energy consumption. Most of this expansion was due to the combustion of fossil fuels, an activity that has resulted in the unprecedented level of human interference in global biochemical cycles. Thus, we must seriously consider the novel and a very sobering possibility that the future limits on human acquisition and conversion of energy may arise from the necessity to keep these cycles compatible with the long-term habitability of the biosphere rather than from any shortages of available energy resources.

Editor's note

This entry is adapted from Vaclav Smil, Global Material Cycles and Energy. In: Cutler J. Cleveland, Editor(s)-in-Chief, Encyclopedia of Energy, Elsevier, New York, 2004, Pages 23-32.

Further Reading

- Browning, K.A. and Gurney, R.J., Editors, 1999. Global Energy and Water Cycles, Cambridge Univ. Press, New York. ISBN: 0521560578

- Condie, K.C., 1997. Plate Tectonics and Crustal Evolution, Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN: 0080348742

- Davies, G.F., 1999. Dynamic Earth: Plates, Plumes and Mantle Convection, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK. ISBN: 0521590671

- Galloway, J.N. and Cowling, E.B., 2002. Reactive nitrogen and the world: 200 years of change. Ambio, 31:64–71.

- Godbold, D.L. and Hutterman, A., 1994. Effects of Acid Precipitation on Forest Processes, Wiley–Liss, New York. ISBN: 0471517682

- Houghton, J.T. et al., 2001. Climate Change 2001. The Scientific Basis, Cambridge Univ. Press, New York. ISBN: 0521807670

- Irving, P.M., Editor, 1991. Acidic Deposition: State of Science and Technology, U.S. National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program, Washington, DC. ISBN: 0160359252

- Smil, V., 1985. Carbon Nitrogen Sulfur, Plenum, New York. ISBN: 0306420260

- Smil, V., 1991. General Energetics: Energy in the Biosphere and Civilization, Wiley, New York. ISBN: 0471629057

- Smil, V., 2000. Cycles of Life, Scientific American Library, New York. ISBN: 0716750791

- Smil, V., 2001. Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN: 026219449X

- Smil, V., 2002. The Earth's Biosphere: Evolution, Dynamics, and Change, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN: 0262194724