Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic

This is Section 11.4 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Author: David R. Klein; Contributing Authors: Leonid M. Baskin, Lyudmila S. Bogoslovskaya, Kjell Danell, Anne Gunn, David B. Irons, Gary P. Kofinas, Kit M. Kovacs, Margarita Magomedova, Rosa H. Meehan, Don E. Russell, Patrick Valkenburg

Coastal people of the Arctic have, throughout history, depended on marine mammals and seabirds as principal subsistence resources. Seabirds have provided eggs and meat and in some cases skins, and various marine mammal products have been used for meat, clothing, heat, light, tools, toys, and a host of other essential components of day-to-day living (e.g., [1]). The great abundance of these animals in the Arctic also attracted attention from the south as early as the 1500s, and large-scale commercial harvests of these animals have been undertaken by a variety of nations within arctic regions – particularly harvests focused on whales and seals. Subsistence harvesting of marine mammals and seabirds currently occurs in most arctic nations. However, hunting intensities differ markedly with community size and density, and the wildlife species present regionally. National and local management regimes are highly varied. Also, the line between commercial and subsistence hunting is not clear, given that some meat as well as skins and tusks from "subsistence" hunts are sold commercially, and sport hunting is conducted on some species within quotas assigned to indigenous communities.

Large-scale commercial harvests of arctic marine mammals are restricted to harp (Phoca groenlandica) and hooded (Cystophora cristata) seals. But non-indigenous people also commercially harvest a variety of species at smaller scales, such as minke whales in Norwegian waters, belugas in the White Sea, and pilot whales (Globicephala melaena) in the Faroe Islands. Sport hunting by non-indigenous peoples is also conducted on grey (Halichoerus grypus) and harbour (Phoca vitulina) seals and to a lesser extent, ringed and bearded (Erignathus barbatus) seals, as well as on a variety of seabird species.

The changes that will occur in hunting patterns due to climate change and the management initiatives that will be necessary to achieve sustainable harvests under new environmental conditions are highly speculative at the moment. Analyses are currently becoming available, such as this assessment, which will help to predict change in the next decades in the Arctic due to climate change (e.g., [2]). Some of the most likely changes are:

- modifying the timing and location of harvest activities;

- adjusting the species and quantities harvested; and

- minimizing risk and uncertainty while harvesting in less stable climatic and ice conditions.

The analyses presented in the rest of this section largely serve to document current management regimes in the arctic countries with respect to marine mammals and seabirds. Hopefully, this will serve to highlight where future climate-related impacts might be dealt with via international measures or within the administration of the various arctic countries. It is important to recognize that the marine and terrestrial environments are not distinct from one another. Marine birds and many marine mammals require a land base for some of their life activities, be it nesting sites for birds, maternal dens for polar bears, or haul-out areas used by many marine mammals for resting, breeding, or giving birth. Also, most arctic residents who harvest marine wildlife live in coastal communities at the interface of land and sea.

Several marine mammal and seabird species are managed in part via international agreements or conventions and management issues are also discussed in international fora such as Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) working groups. For example, polar bear research and management is coordinated internationally via the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group. This group was formed following the first international meeting on polar bear conservation, held in Fairbanks, Alaska in 1965, and subsequently led to the development and negotiation of the International Agreement for the Conservation of Polar Bears and their Habitat, which was signed in Oslo, Norway in 1973. The agreement came into effect for a five-year trial period in 1976. It was unanimously confirmed for an indefinite period in January 1981. This agreement stipulates that the contracting parties will conduct national research programs on polar bears related to the conservation and management of the species, will coordinate such research with research carried out by the other parties, will consult with the other parties regarding management of migrating polar bear populations, and will exchange information on research and management and data on bears taken[3]. A treaty between the United States and Russia defines a Bilateral Agreement for the Conservation of Polar Bears in the Chukchi/Bering Seas that deals with the management of this specific polar bear stock[4]. The North Atlantic Fisheries Organization’s Harp and Hooded Seal Working Group performs a similar role regarding coordination of the management of stocks of these two commercially harvested seal species. The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission is another international body that promotes cooperation on the conservation, management, study, and sustainable use of marine mammals in the North Atlantic. The International Whaling Commission sets quotas for the commercial harvest of all large cetacean species (currently operating with a total moratorium on commercial harvesting), and also provides a format for discussions regarding small cetaceans. The North Pacific Fur Seal Treaty regulated harvesting of the northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) between Japan, Russia, United States, and Great Britain (for Canada) from early in the 1900s until 1985, when the commercial hunt was terminated. A Joint Commission on Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga was established in 1989 to address conservation and management of stocks that migrate between Canadian and Greenland waters. Organizations operating within the Arctic Council, such as CAFF, are playing an increasing role as advisory bodies in conservation and management of sea mammals and seabirds, largely via international working groups. For example, the CAFF Circumpolar Seabird Working Group recently produced the International Murre Conservation Strategy and Action Plan[5] that identifies management issues related to common (Uria aalge) and thick-billed (U. lomvia) murres, which experienced significant declines in several circumpolar countries throughout the twentieth century. This group has also developed the International Eider Conservation Strategy[6]. Not all international agreements are legally binding, however, and most legislation regarding wildlife management is undertaken at the national level within the various arctic countries.

The following sections discuss the basic characteristics of management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds for the main arctic regions. Further information on these regions may be found in Chapter 13 (Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic).

Contents

Russian Arctic (11.4.1)

Along with the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone adjacent to its boundaries, the Russian Arctic region accounts for over 30% of the area of the Russian Federation. The Russian continental shelf in the Arctic extends to the greatest distance and has the largest area of any country in the world. The associated shoreline and the area of the basins drained by the Russian rivers flowing into the Arctic Ocean are both huge. The region comprises the Central Arctic zone (roughly north of 80° N) and the Atlantic, Siberian, and Pacific sectors. The Russian Arctic, in particular the Atlantic and Pacific sectors, is characterized by a great diversity of marine ecosystems. Sea ice has an exceptionally important role in the life of marine mammals and birds of the Arctic. The nature of the sea-ice cover and the system of stationary polynyas and ice leads essentially determine the intra-specific structure, dynamics of number of species and populations, and the dates and pathways of their seasonal migrations. Of the marine mammals, the walrus alone is capable of successfully breaking gray ice 10 to 15 centimeters (cm) thick, and adult bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) break gray-white ice up to 15 to 30 cm thick with their backs. But similar to other marine mammals and birds, walruses and bowhead whales completely depend on the sustainable system of clear water space between pack-ice fields for their northward progress. A number of arctic marine mammal and bird species are circumpolar, and are represented by several populations and even subspecies (e.g., the bowhead whale, walrus, bearded seal, ringed seal, herring gull (Larus argentatus), glaucous gull (L. hyperboreus), and kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla)). They may be fairly isolated geographically as are the Svalbard and Chukchi–Bering sea stocks of the bowhead whale, Atlantic and Pacific subspecies of the walrus, and populations of the same species of seabirds of the Atlantic and Pacific sectors, but occasionally are only separated by massifs of heavy pack ice (the Laptev and Pacific subspecies of the walrus). There are some species that dwell in contiguous regions of Norway and the United States. The Russian Arctic also provides feeding grounds for some southern species, for instance, the Californian gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and short-tailed shearwaters (Puffinus tenuirostris) that nest in southern Australia. A number of species and populations have been classified as rare and protected and accordingly are listed in the Red Data Books of the IUCN and the Russian Federation.

Climate changes have occurred repeatedly in the history of the Arctic. The entire arctic zone exhibited a warming trend during 1961 to 1990; the region from 60° to 140° E (i.e., a substantial part of the Russian Siberian Arctic) showed the greatest warming. Over the last 30 years changes in sea ice have been in conformity with that of the warming trend. The climate, however, in different sectors of the Russian Arctic, both in the past and today, has been variable[7]. The causal connection between global and regional changes in climate, on the one hand, and the number and distribution of arctic marine mammals, on the other, is far more complex than commonly believed. Despite switches between warming and cooling periods, the ranges for the majority of higher vertebrates of the Russian Arctic have been fairly stable over the last millennia. This is confirmed by dating the remains of whales, pinnipeds, and birds (1,500 to 2,680 years) from ancient coastal villages on the Chukchi Peninsula, located on the main migration routes of the animals, and in their breeding and feeding areas[8].

Animals of the marine environment are capable of maintaining and even expanding their ranges owing to physiological, biochemical, and behavioral mechanisms for adaptation to changing environmental conditions. An example is found in the Californian gray whale. Migrating between the feeding areas in the Bering Strait, Chukchi Sea, and East Siberian Sea and the breeding areas in the subtropical lagoons of Mexican California, gray whales annually cover 18,000 to 20,000 kilometers (km). This huge migration route covers over 50° of latitude and exposes whales to the effects of constantly changing environmental factors, in particular the strong fluctuations in temperature and photoperiod.

In marine ecosystems, it is primarily the higher vertebrates that have been the most threatened by the rapidly developing direct consequences of human activities, now aggravated by climate change. The increased rate of these impacts frequently exceeds the adaptive capacities of living organisms. Over-harvest of the fish resources of the Barents Sea, primarily capelin (Mallotus villosus), resulted in profound rearrangements of the trophic relationships of the entire marine ecosystem, causing massive mortality of marine colonial birds and harp seals in the late 1980s. In 1988, on the southern island of Novaya Zemlya, fish-eating marine birds switched to a zooplankton diet[9].

Throughout the 1990s the economic development activities that caused these detrimental processes increased many times due primarily to sharp increases in oil and gas production in the coastal regions and increased ship transit through polynyas and stationary ice leads, which are vital for marine mammals and birds in the high latitudes. This was most pronounced in the Atlantic sector. Pollutants associated with these activities and those from industrial activities on land that reach the sea through the major river systems flowing into the arctic seas have been found at all trophic levels of the biota, frequently causing morbidity and mortality of marine animals. In the early 1990s maps were compiled indicating levels of pollution by heavy metals, organochlorine compounds, petroleum products, and phenols in surface waters and bottom sediments of the seas of the Russian Arctic[10].

In the former Soviet Union, the Arctic was never legally defined geographically. Depending on current needs of the state, the southern border of the Arctic was delineated to serve immediate and short-term interests. The Soviet government apparently intended to extend the [[region]’s] northern boundary to the North Pole but never made a full-scale claim over such a Soviet Arctic sector. The Soviet Arctic was always classified as a closed frontier zone and administrated accordingly. All services, including those purely civil, were to a large extent included in the classified status. This also applied to environmental monitoring of terrestrial and marine areas, and particularly to plant and wildlife species. In present-day Russia this situation has, nevertheless, deteriorated. The limited system of arctic environment monitoring, developed in Soviet times, was virtually discontinued. For lack of funds, no new national parks or coastal and marine reserves and sanctuaries were established through federal, regional, or local jurisdictions. Existing protected areas, for lack of financing, have had funding reduced or eliminated for research as well as for protection from detrimental human activities[11]. The network of specialized marine sanctuaries, reserves, and parks considered necessary for protection of arctic cetaceans and pinnipeds has not had any significant development.

The Parliament (Federal Assembly) of the Russian Federation has so far enacted no law, amendment, or supplement to the current laws on the protection of the arctic environment. Moreover, the term "Arctic" is absent from the federal legislation. In some instances the term "Extreme North" is used, but this term is not used in international documents. No national arctic doctrine has been elaborated to reflect the many diverse interests of the Russian society in the Arctic, including protection of polar marine ecosystems. Thus, the Russian situation is unique. Federal governing bodies have signed a number of important international acts and bilateral agreements on the environment and sustainable development of the Arctic, but national legislation or statutory framework for management and protection of the arctic ecosystems has not been developed. At present no adequate legal framework exists for management and protection of the marine ecosystems of the Arctic and the associated species, subspecies, and populations of birds and mammals. There are, however, international documents, including ratified conventions and agreement on a number of species.

Fig. 11.9. Commercial harvest of harp and hooded seals by Russian vessels since the mid-1940s (East and West Ice combined). (Source: ACIA)

Fig. 11.9. Commercial harvest of harp and hooded seals by Russian vessels since the mid-1940s (East and West Ice combined). (Source: ACIA) Russia is a member of the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group and operates under a 1973 International Polar Bear Agreement. In fact, polar bear hunting was banned in the former Soviet Union in 1956 and until very recently only problem polar bears could be killed[12]. However, the level of protection has diminished recently due to economic and political changes that make nature conservation and control of the use of the environment ineffective, and an increased interest by Russian people in using polar bears as a resource has been expressed. An agreement signed by the Government of the United States and the Russian Federation on October 16, 2000, recognized the need of indigenous people to harvest polar bears for subsistence purposes. It includes provisions for developing sustainable harvest limits, allocation of the harvest between jurisdictions, and the need for compliance and enforcement. Half the harvest limit, which is yet to be decided, will be allotted to each country. The agreement reiterates requirements of the multi-lateral polar bear agreement and restricts harvesting of denning females, females with cubs, or cubs less than one year old, and prohibits use of aircraft, large motorized vessels, snares, or poison. The agreement does not allow hunting for commercial purposes or commercial uses of polar bears or their parts. It commits the partners to the conservation of ecosystems and important habitats, with a focus on conserving specific polar bear habitats such as feeding, congregating, and denning areas. Mechanisms to coordinate management programs with the Chukotka government and with the Chukotka indigenous organizations are currently being determined. The agreement is currently undergoing procedural handling by the U.S. Congress and required legislative steps in Russia are being determined[13].

Other marine mammal harvests within Russia are managed on the basis of Total Allowable Catches (TACs) that are assigned by species and geographical region (Table 11.4). Catches of commercial species such as harp and hooded seals have remained constant over the last few decades (Fig. 11.9). However, reporting of harvest statistics and enforcement of TACs is difficult to manage in outlying areas given Russia’s current economic and administrative difficulties and the status of populations and their harvests is in reality largely unknown.

|

Table 11.4. Total allowable catches of marine mammals in Russia for 2002[14]. | |||||||||

|

Western Bering Sea |

Eastern Kamchatka |

Sea of Okhotsk |

Caspian Sea |

Barents Sea |

White Sea | ||||

| Karaginskaya | Petropavlovsk- Komandorskaya | Northern Sea of Okhotsk | Western Kamchatskaya | Eastern Sakhalinskaya | |||||

|

White whale |

300 | 400 | 100 | 200 | 500 | 50 | |||

| Killer whale | 5 | ||||||||

| Northern fur seal | 3,400 | 1,800 | |||||||

| Walrus | 3,000 | ||||||||

| Ringed seal | 5,900 | 600 | 18,500 | 6,000 | 3,500 | 1,500 | 1,100 | ||

| Ribbon seal | 5,800 | 200 | 9,000 | 500 | 5,500 | ||||

| Bearded seal | 4,000 | 4,800 | 1,900 | 700 | 250 | 100 | |||

| Caspian seal | 500 | ||||||||

| Note:Total Allowable Catch of white whales, killer whales and walruses are given for subsistence needs of small peoples of the North and Far East and for scientific and cultural-educational purposes. | |||||||||

Indigenous people in Russia have collected seabirds and their eggs since ancient times. Non-indigenous people have also harvested seabirds in coastal areas since the colonization of northwest and northeast Russia more than two centuries ago[15]. In the Barents Sea region tens of thousands of eggs were collected annually from the middle of the 19th century until the beginning of the 20th. During the 1920s and early 1930s the number of eggs collected increased dramatically. For example, at Besymyannaya Bar, Novaya Zemlya 342,500 murre eggs were collected and more than 12,000 adult birds were killed in the 1933 season alone[16]. The need for conservation was recognized at the time, and several state reserves were established in the late 1930s where egg collecting and bird harvesting were prohibited. In the Commander Islands, near Kamchatka in the southern Bering Sea, seabird exploitation began with the first Russian expeditions to the area. Pallas’s cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus) was harvested heavily and this is thought to have contributed to the extinction of this species. In the 19th century the Commander Islands were settled by Russians and Aleuts. These established residents began to harvest eggs and birds in the tens of thousands annually. Their preferred species were northern fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis), pelagic cormorants (P. pelagicus), thick-billed murres, horned puffins (Fratercula corniculata), tufted puffins (F. cirrhata), and glaucous-winged gulls (Larus glaucescens). In Kamchatka, local people collected 4,000 to 5,000 glaucous-winged and black-headed (L. ridibundus) gull eggs annually in the past, but the collection is thought to be negligible currently.

Traditional patterns of harvesting seabird eggs continued despite national hunting regulations prohibiting harvest of eggs of all bird species everywhere in Russia. In the Murmansk region however, local hunting regulations permit hunting of alcids (auks, puffins, guillemots, etc.) in autumn and winter[17]. All four eider species are protected along the entire coast of Russia. It is known that some illegal harvesting takes place due to a general lack of enforcement. In the Barents Sea region it is thought that thousands of eggs are collected annually[18]. It is known that 2,000 glaucous-winged gull eggs were collected in 1999 and again in 2001 from Toporkov Island, where the largest colony of the species exists among the Commander Islands[19]. Illegal egg collecting is also known to be a common activity among inhabitants of villages and crews of visiting vessels in the northern Sea of Okhotsk and human influences on easily accessible colonies of common eiders has increasingly been evident on the northern coast of the Koryak Highlands, Chukotka. The need to improve seabird management plans, conservation laws, and hunting regulations is recognized[20].

The scientific community of Russia, the indigenous minorities of the North, and the non-governmental environmental organizations have been campaigning for a refinement of the legislative framework regarding the Arctic. There are, however, few examples of fruitful cooperation between governmental bodies and indigenous and local organizations for management and protection of the natural environment of the Arctic. One positive example, however, concerns the 25-year monitoring of marine mammals and their harvest by the indigenous Inuit and Chukchi peoples of the Chukchi Peninsula, associated with Russian participation in the International Whaling Commission. These activities have been possible through the active role and support of agencies of the U.S. government responsible for marine mammal and bird conservation and management, and indigenous peoples’ corporations of Alaska.

Canadian Arctic (11.4.2)

Polar bear harvesting in Canada is undertaken in accordance with the 1973 International Polar Bear Agreement. Between 500 and 600 polar bears are taken annually in Canada by Inuit and Amerindian hunters under a system of annual quotas that is reviewed annually in Nunavut, the NWT, Yukon Territory, Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, and Newfoundland/Labrador. Within the quota assigned to each coastal village in the NWT and Nunavut, hunters are allowed to allocate a number of hunting tags to nonresident sport hunters, who are guided by local Inuit hunters. Sport hunting and the sale of skins are important sources of cash income for small settlements in northern Canada. The annual economic value of the polar bear hunt is about one million Canadian dollars[21]. The Canadian Wildlife Service represents Canada in the International Polar Bear Working Group.

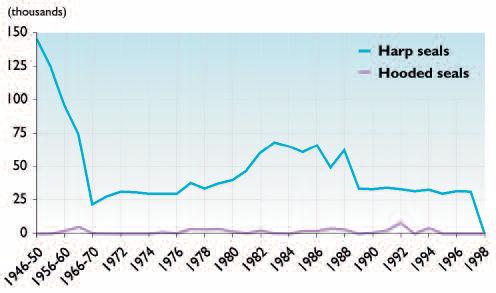

Seal and whale management falls within the jurisdiction of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) at the federal level. Harp and hooded seals are commercially hunted using a quota system in Canadian waters and shared stocks with Greenland involve some co-management. For 2002, the TAC for harp seals was 275,000 and for the hooded seal 10,000[22]. Sale, trade, or barter of harp seal white-coat pups or hooded seal blue-backs (pups) is prohibited under Canada’s Marine Mammal Regulations. The use of vessels over 65 feet (ft) (19.8 meters [m]) in length is also prohibited. The actual number of animals harvested varies from year to year depending on sea-ice conditions, market prices, or subsidy systems (Fig. 11.10), although the actual harvest quota has remained constant in recent years. Some subsistence hunting of harp and hooded seals takes place in northern regions, but this hunt only numbers a few thousand animals. Grey seals are harvested in a small, traditional commercial hunt in an area off the Magdalen Islands and at a few locations in the Maritimes. The numbers taken are small and thus a TAC has not been established. Ringed seals and bearded seals are taken in subsistence harvests in Labrador and throughout the Canadian Arctic, but figures are not available regarding harvest levels. Ringed seals are by far the most important arctic seal for human consumption and utilization in the Canadian Arctic. The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board has conducted a five-year harvest study on all species of seals and the resulting report is available via their website. Subsistence hunting of arctic seals is not regulated.

Fig. 11.10. Commercial catches of harp and hooded seals in Canadian waters since 1950. (Source: From seal catch data for Canada, Norway, and Russia collated at the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Polar Environmental Center, Tromsø, Norway)

Fig. 11.10. Commercial catches of harp and hooded seals in Canadian waters since 1950. (Source: From seal catch data for Canada, Norway, and Russia collated at the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Polar Environmental Center, Tromsø, Norway) Commercial harvesting of walrus was banned in Canada in 1931. All hunting currently conducted is indigenous subsistence hunting. Walrus harvest regulations are undergoing changes with the establishment of Nunavut but currently, residents of Coral Harbour, Sanikilqaq, Arctic Bay, and Clyde River have DFO-established quotas, and all other Inuk residents are permitted to hunt up to four walrus per year. Similar to the situation for polar bears, communities can set some of their quota aside for sport hunting by non-indigenous people[23]. Four Atlantic walrus stocks occur in the eastern Canadian Arctic: Foxe Basin, Southern and Eastern Hudson Bay, Northern Hudson Bay–Hudson Strait– Southern Baffin Island–Northern Labrador, and the North Water (Baffin Bay–Eastern Canadian Arctic). The status of three of the four is classified as poorly known and the fourth is "fair". In the latter case, the stock is currently being harvested at a removal rate of 300 animals, which may exceed sustainable yield[24]. There is a similar concern regarding the North Water stock and the Southern and Eastern Hudson Bay stocks. The final stock is so poorly known that it is not reasonable to attempt to determine whether current harvest levels are sustainable or not.

Canada discontinued commercial whaling in 1972. However, whaling has been important to Inuit in the Arctic since prehistoric times and Arctic Inuit currently hunt about 700 beluga and about 300 narwhal annually in Canada. There is concern for the conservation of several beluga stocks in eastern Canada, while those in the west are harvested well within sustainable yields[25]. The St. Lawrence River population is endangered, although it has been completely protected from hunting since 1979. Also, populations in Southeast Baffin Island–Cumberland Sound and Ungava Bay are endangered, and the Eastern Hudson Bay population is threatened. The Eastern High Arctic/Baffin Bay population is classified as a special concern. Subsistence hunting of belugas in some parts of the Arctic is a concern because of its potential to cause continued decline or lack of recovery of depleted populations[26]. Narwhal are hunted in Hudson Bay and Baffin Bay under a quota system in 19 communities[27]. Baffin Bay narwhals summer in waters that include areas in northwestern Greenland and thus are a shared stock. Recent reviews of these stocks have been performed in consideration of new management options for this species.

Hunting of bowhead whales has recently been resumed in both the eastern and western Canadian Arctic following the settlement of land claim agreements, based on the traditional cultural value of these hunts[28]. Both bowhead whale populations are classified as endangered[29]. Harvesting of these populations violates the intent of the International Whaling Commission[30], although Canada is not a member of this whaling regime. Subsistence whaling is currently managed under three separate land claim agreements – the James Bay Northern Quebec agreement, the Inuvialuit Final Agreement, and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement – in the Canadian North.

Seabird harvesting in Canada dates back thousands of years to early colonization by indigenous peoples. Historically, seabirds were an important component of the subsistence lifestyle for coastal peoples, but today seabird harvesting for birds and eggs is much less widespread, although improved hunting technologies have tended to increase harvests on species such as murres[31]. Regulation of seabird harvesting (with the exception of cormorants and eiders) is done under the Migratory Bird Convention Act of 1917 that protects them year-round from hunting. Indigenous people in Canada are exempt from this restriction and can at any time take various auk species and scoters (Melanitta spp.) for human food and clothing. Eiders are hunted as game birds by both indigenous and non-indigenous people in a controlled annual hunt. Seabird egg collecting is not permitted under the general terms of the convention, but indigenous people are allowed to take auk eggs[32].

Common eiders, thick-billed murre, and black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) are the most commonly harvested seabird species in arctic Canada, and are utilized by indigenous people wherever they are available[33]. There is no comprehensive monitoring of seabird harvests in Canada, but the total annual seabird take in the Arctic is thought to number about 25,000 individuals, about half of which are common eiders. Egg collecting is not as widespread as bird hunting, and has usually involved ground nesting species such as common eiders, Arctic terns (Sterna paradisaea), and gulls, which is technically illegal, as well as little auks (Alle alle). It is thought that some few thousand eggs are collected annually[34]. The most intense consumptive use of seabirds in Canada occurs in Newfoundland and Labrador, where thick-billed and common murres are harvested based on a set hunting season and bag limits. In the past, hunting levels were extreme, and recently enacted legislation is attempting to bring the harvest to sustainable levels. Currently, 200,000 to 300,000 murres are shot in the Newfoundland/Labrador hunt and approximately 20,000 common eiders are taken in Atlantic Canada. Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), dovekie (little auk), razorbills (Alca torda), and black guillemots are legally hunted in Labrador. Illegal harvesting of other species such as shearwaters (Puffinus spp.), gulls, and terns is also known to occur[35]. Seabird harvests on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec were considered large enough to have reduced seabird populations, but a recent education program is thought to have reduced local hunting pressure to a level where population recovery is expected[36]. One of the primary needs for improving the management of seabird harvests in Canada is to improve knowledge regarding the current level of seabird harvesting, particularly in regions where harvest is thought to be substantial but little information exists[37]. The Canadian Wildlife Service, in cooperation with various indigenous wildlife management boards, co-manages seabirds in the Arctic.

Fennoscandian North (11.4.3)

Marine mammal harvesting has been a tradition in Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland for centuries. Norway and Greenland, the only Fennoscandian countries that have polar bears, are both signing members of the International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears (IACPB). Denmark signed the original agreement, but Greenland Home Rule took over legal responsibility for management of renewable resources, including polar bears, in 1979. Polar bears are completely protected in Svalbard[38]. Only bears causing undue risk to human property or life have been shot since the closure of the harvest some decades ago; these cases are dealt with under the authority of the Governor of Svalbard, which acts under the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Justice. Polar bears are legally harvested in Greenland. Full-time, licensed hunters have taken an average of 150 bears per year in Greenland in recent decades in accordance with most international recommendations for harvesting, although some local rules in some regions do not entirely conform to the IACPB[39]. The Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, which has been operating since 1995, is concerned that polar bears may require increased protection in Greenland.

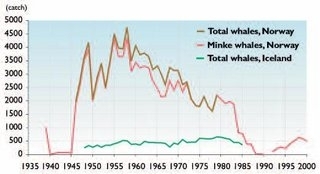

Fig. 11.11. Commercial catches of harp and hooded seals in the West Ice by Norwegian vessels since the mid-1940s. (Source: From seal catch data for Canada, Norway, and Russia collated at the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Polar Environmental Center, Tromsø, Norway)

Fig. 11.11. Commercial catches of harp and hooded seals in the West Ice by Norwegian vessels since the mid-1940s. (Source: From seal catch data for Canada, Norway, and Russia collated at the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Polar Environmental Center, Tromsø, Norway) In Norway, harp seals and hooded seals are commercially harvested, based on government-set quotas. The harp and hooded seal harvests are managed in agreement with the North Atlantic Fisheries Organisation. Current harvest levels are low compared to takes early in the 20th century (Fig. 11.11), and are set within sustainable limits. Ringed seals and bearded seals can be freely harvested in Svalbard outside their respective breeding seasons, but actual takes are very low. Harbour seals on Svalbard are Red Listed, and are completely protected. Coastal seals along the northern coast of Norway, which include grey and harbour seals as well as small numbers of ringed and bearded seals, are hunted through species-based quotas and licensing of individual hunters. Grey seals and harbour (common) seals are harvested in Iceland; catches of these two species have dropped gradually over recent decades and currently about 1,000 harbour seals and a few hundred grey seals are caught annually. In Greenland, about 170,000 seals are taken annually, mainly harp and ringed seals. They are an important source of traditional food, and about 100,000 skins are sold annually to the tannery in Nuuk, Greenland[40]. There are few national regulations in Greenland regarding seal hunting; there are four Executive Orders, two related to catch reporting, one banning exportation of skins from pups, and the fourth is a regulation on harbour seal hunting in spring. There is concern that harbour seals may be in threatened status in Greenland[41]. With the exception of harbour seals, Greenland’s seal stocks are plentiful.

Walruses were commercially harvested in Svalbard historically, to the brink of extirpation, but are now totally protected and are recovering[42]. The walrus population that winters off central West Greenland is harvested at a level that is thought to exceed sustainable yield[43]. Approximately 65 walruses are taken annually from this area where only about 500 animals remain. The same is true of the North Water stock that winters along the west coast of Greenland as far south as Disko Island. At this location about 375 walruses are taken annually from a group that only numbers a few thousand. In East Greenland, the small harvests focus mainly on adult males, and are thought to be within the replacement yield.

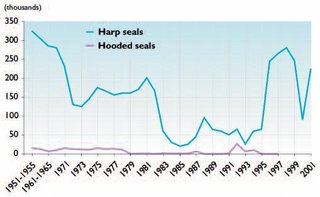

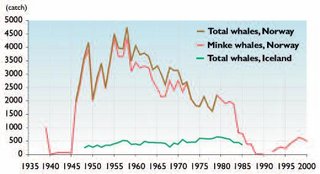

Fig. 11.12. Commercial catches of cetaceans in Norway and Iceland since 1939. (Source: Whale harvest data for Iceland from the Marine Research Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland; and for Norway from Statistisk Sentralbyrå, Oslo, Norway)

Fig. 11.12. Commercial catches of cetaceans in Norway and Iceland since 1939. (Source: Whale harvest data for Iceland from the Marine Research Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland; and for Norway from Statistisk Sentralbyrå, Oslo, Norway) Whaling has been a traditional undertaking in Norway for centuries. However, cetaceans, large and small, with the exception of minke whales, are completely protected in Norwegian waters currently. Approximately 600 minke whales have been taken annually in recent years in the commercial hunt in Norwegian waters (Fig. 11.12). Management of this harvest is the responsibility of the Ministry of Fisheries, as is the case for all commercial marine mammal hunting in Norway. The harvest quota for minke whales is set by the Norwegian Government. This harvest is considered sustainable, and was sanctioned by the Scientific Advisory Board of the International Whaling Commission, but is in violation of the International Whaling Commission’s total ban on commercial whaling. Norway, however, has entered a reservation against the moratorium, so its harvest is not strictly speaking a violation of International Whaling Commission decisions. Some poaching of harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) is thought to take place along the Finnmark coast, but the level of this harvest is unknown. Although Iceland is technically not currently whaling commercially (Fig. 11.12), it was announced in August 2003 that Iceland would begin culling minke whales for "scientific purposes"; Iceland has been importing whale meat from the Norwegian minke whale harvest. In the Faroe Islands whales are harvested for local meat consumption. The majority of the harvest is pilot whales. The hunt has ranged from a few hundred animals to a few thousand in recent years. Other species are also taken, although less frequently, including humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), harbour porpoises, and white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus). Indigenous people in Greenland continue their long tradition of subsistence whaling. The harvests currently focus mainly on white whales and narwhal coastally, but fin and minke whales are also taken, as well as pilot whales sporadically, and killer (Orcinus orca) and humpback whales have been taken on occasion. The fin and minke whale catches are sanctioned by the International Whaling Commission[44], within the agreements for indigenous subsistence whaling. West Greenland is permitted an annual catch of 19 fin whales. West Greenland has an annual quota of 175 minke whales and East Greenland can take up to 12 of this species annually (until 2006). The Institute of Natural Resources, of the Home Rule Government, has documented that beluga have declined due to overexploitation in Greenland, and suggests that this species needs increased protection along with the narwhal and harbour porpoise (Fig. 11.13). The Greenland Home Rule Government is currently revising the management plan and hunting regulations for small cetaceans[45].

The cultural traditions for seabird harvesting in the Fennoscandian North are varied. In Finland there is no tradition for hunting alcids. Species such as eiders, oldsquaw (Clangula hyemalis), common merganser (Mergus merganser), and red-breasted mergansers (M. serrator), are hunted by set seasonal open and closing dates. Egging has been forbidden since 1962, with the exception of the autonomous region of the Åland Islands in the southwest archipelago[46]. This region has its own hunting act that regulates the take of seabirds. Present harvests in Finland are thought to be sustainable; selling harvested birds is not allowed. In Iceland, there is a long tradition of harvesting seabirds, including northern fulmars, Arctic terns, black-headed gulls, great (Larus marinus) and lesser (L. fuscus) black-backed gulls, herring gulls, glaucous gulls, eiders, Atlantic puffins, common and thick-billed murres, razorbills, and black-legged kittiwakes[47]. Great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), shags (P. aristotelis), black guillemots, and northern gannets (Sula bassanus) are also harvested but to a lesser degree, and eggs of gulls, terns, and sometimes eiders are also collected, although there are no records of egg numbers[48]. Eider down is also utilized. Seabird meat is sold in Iceland, and there has been increasing market demand for this during the last 10 to 15 years as a specialty item for tourists. The Ministry of the Environment supervises the Act on Conservation, Protection, and Hunting of Wild Birds and Land Mammals in Iceland. Seasons are set for shooting individual bird species, but the periods for egg collecting and catching of young are not specified. Three gull species that are classified as pests can be killed year-round. Information on current population sizes and the effects of harvesting, as well as more information on egg collecting, is needed to improve managements of seabird harvests in Iceland[49].

The Faroe Islands have a long tradition of seabird harvesting that continues today. The two dominant target species are northern fulmars and puffins. Norway also has a long tradition of harvesting marine birds. Down collecting and harvesting eggs, adult birds, and chicks have been important subsistence and commercial activities for rural residents of coastal northern Norway[50]. Significant hunting and collecting have also taken place at Bjørnøya and Svalbard until recent decades. Currently, hunting is only permitted on a small number of marine birds (Svalbard northern fulmar, thick-billed murre, black guillemot, and glaucous gull; mainland – great cormorant and shag, greylag goose, oldsquaw and red-breasted merganser, black-headed gull, common gull, herring gull, great black-backed gull, and black-legged kittiwake) during set seasons. Egg collecting is permitted from herring gulls, great black-backed gulls, common gulls, and blacklegged kittiwakes early in the laying season. Eider eggs are collected only in areas where construction of nest shelters for eiders is traditional. Harvests within Norway are considered within sustainable limits, but there is concern that some seabird stocks shared with Russia and Greenland may currently be excessively harvested[51] (Table 11.5).

|

Table 11.5. The status of marine birds breeding in the Barents Sea region[52]. | ||||

|

National Red Lista |

Bern Conventionb |

Bonn Conventionc | ||

| Norway | Russia | |||

| Great northern diver (Gavia immer) | R | II | II | |

| Northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) | III | |||

| European storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus) | II | |||

| Leach’s storm-petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) | II | |||

| Northern gannet (Morus bassanus) | III | |||

| Great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) | III | |||

| European shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) | R | III | ||

| Greylag goose (Anser anser) | III | II | ||

| Barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis) | II | II | ||

| Brent goose (Branta bernicla) | V | R | III | II |

| Common eider (Somateria mollissima) | III | II | ||

| King eider (Somateria spectabilis) | II | II | ||

| Steller eider (Polysticta stelleri) | II | I/II | ||

| Long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis) | DM | III | II | |

| Black scoter (Melanitta nigra) | DM | III | II | |

| Velvet scoter (Melanitta fusca) | DM | III | II | |

| Red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator) | III | II | ||

| Eurasian oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) | III | |||

| Purple sandpiper (Calidris maritima) | II | II | ||

| Ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres) | R | II | II | |

| Red-necked phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus) | II | II | ||

| Grey phalarope (Phalaropus fulicarius) | V | II | II | |

| Arctic skua (Stercorarius parasiticus) | III | |||

| Great skua (Catharacta skua) | III | |||

| Sabine’s gull (Xema sabini) | R | II | ||

| Black-headed gull (Larus ridibundus) | III | |||

| Mew gull (Larus canus) | III | |||

| Lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) | Ed | |||

| Herring gull (Larus argentatus) | ||||

| Glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus) | III | |||

| Great black-backed gull (Larus marinus) | ||||

| Black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) | III | |||

| Ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea) | DM | R | II | |

| Common tern (Sterna hirundo) | II | II | ||

| Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) | III | II | ||

| Common murre (Uria aalge) | V | III | ||

| Thick billed murre (Uria lomvia) | III | |||

| Razorbill (Alca torda) | R | III | ||

| Black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) | DM | III | ||

| Little auk (Alle alle) | III | |||

| Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica) | DC | III | ||

| aCategories: E (Endangered),V (Vulnerable), R (Rare), DC (Declining, care demanding), DM (Declining, monitor species); bII should be protected against all harvesting, III should not be exploited in a way that may threaten their populations; cI includes species that are considered threatened by extinction. II are not threatened by extinction,but international co-operation is needed to ensure protection; dRed List for Svalbard only. | ||||

Fig. 11.13. Harvests of some seabird and marine mammal species for sale in country food markets (as shown here at Nuuk, Greenland in 1991) may exceed the sustainability of their populations, justifying setting of harvest quotas and establishment of protected areas. (Source: Photograph by D.R. Klein)

Fig. 11.13. Harvests of some seabird and marine mammal species for sale in country food markets (as shown here at Nuuk, Greenland in 1991) may exceed the sustainability of their populations, justifying setting of harvest quotas and establishment of protected areas. (Source: Photograph by D.R. Klein) Seabird harvesting in Greenland has a long history and continues to have a key role in Greenland’s subsistence hunting. Murres and eiders are the most heavily harvested species, but others such as dovekies and kittiwakes are also harvested frequently in some regions of the country (Fig. 11.13). There are acknowledged management problems and murres, eiders, and Arctic terns have all recently declined due to overexploitation. For example, the number of thick-billed murre breeding colonies has been reduced from 48 to 23 during the last 30 years on the west coast of Greenland[53]. This is the result of over-harvesting eggs and adult birds. The colonies closest to human settlements have been the most impacted. Prior to the 20th century, communities in Greenland were small and hunting was done from kayaks, which resulted in little impact on seabirds. However, the human population has increased substantially, motorboats and shotguns are now common hunting tools, and the resulting increased harvest has brought about a drastic decrease in the number of formerly large colonies – particularly for murres[54]. Commercial harvests of tens of thousands of birds have been conducted annually since 1990 in southern Greenland municipalities. Most of this hunting pressure takes place in autumn and winter. In northwest and East Greenland seabirds have always been exploited during the breeding period; the only time that they are available in the region. In an attempt to prevent further reductions in the murre breeding population, a closed season was introduced north from Kangatsiaq Municipality in the late 1980s. Subsequent interviews and meetings with hunters showed that illegal hunting continued to be intensive through much of the breeding period[55]. This illegal harvesting, particularly in the Upernavik District, is thought to be a serious threat to breeding colonies. In the small settlements of Avanersuaq and Ittoqqortoormiit, murre shooting is permitted throughout the year. By-catch in fishing nets and increased disturbance near colonies by boat and helicopter traffic are thought to be factors additional to hunting contributing to the reduction in seabird populations. A complete ban was put in force in 1998 on collecting murre eggs, but harvesting continued illegally in some regions[56]. More restrictive legislation on seabird harvesting was put in place on 1 January 2002, but was later retracted due to complaints from hunters. This was followed by attempts to revise existing legislation. Enforced hunting bans will be necessary in some important areas[57] to bring about population recovery.

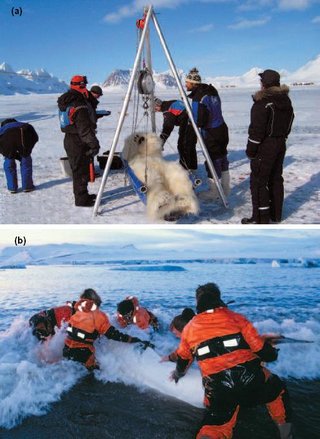

Fig. 11.14. Recent advances in electronic technology and methodology for handling arctic marine mammals allows for collection of data on movements, seasonal habitat preferences, food chain relationships, and other aspects of their social behavior and ecosystem relationships that were previously unavailable to those responsible for their management and conservation. Shown here (a) on the sea ice adjacent to Svalbard, an anesthetized polar bear is being weighed and other biological data collected prior to its release by a team of scientists from the Norwegian Polar Institute. In (b) a similar team is releasing a beluga whale in the waters adjacent to Svalbard after having glued a package to its back containing environmental sensing instrumentation, a data logger, and a radio transmitter capable of sending data to receivers in aircraft, ships, and polar-orbiting satellites. (Source: Photographs by Kit Kovacs and Christian Lydersen, Norwegian Polar Institute)

Fig. 11.14. Recent advances in electronic technology and methodology for handling arctic marine mammals allows for collection of data on movements, seasonal habitat preferences, food chain relationships, and other aspects of their social behavior and ecosystem relationships that were previously unavailable to those responsible for their management and conservation. Shown here (a) on the sea ice adjacent to Svalbard, an anesthetized polar bear is being weighed and other biological data collected prior to its release by a team of scientists from the Norwegian Polar Institute. In (b) a similar team is releasing a beluga whale in the waters adjacent to Svalbard after having glued a package to its back containing environmental sensing instrumentation, a data logger, and a radio transmitter capable of sending data to receivers in aircraft, ships, and polar-orbiting satellites. (Source: Photographs by Kit Kovacs and Christian Lydersen, Norwegian Polar Institute) A major obstacle for the management and conservation of marine mammals in the North Atlantic, as elsewhere in the Arctic, has been the limited information available on the general biology of marine mammals, their distribution and seasonal movements, use of marine habitats, food chain relationships, and general ecology. This is understandable in view of the difficulty of carrying out research in the marine environment of the Arctic and studying animals that spend most or all of their lives at sea, much of which is below the sea surface. Recently developed technology, however, enables monitoring of movements, feeding behavior, and aspects of the general ecology of marine mammals. These techniques can also provide essential information on the relationship of marine mammals to commercial fisheries, needed to base conservation efforts and to develop management plans (Fig. 11.14).

Alaskan Arctic (11.4.4)

Physical changes in the marine system have the capability to dramatically affect marine species. Marine mammals that depend upon sea ice, such as walrus, polar bears, and the several species of ice seals, use ice as a platform for resting, breeding, and rearing young. While sea ice is a dynamic environment, general seasonal patterns exist and subsistence harvest practices have developed in concert with these seasonal rhythms. Hunters have reported changes in winds, sea-ice distribution, and sea-ice formation that particularly affect hunting[58]. Winds are reported to be stronger now compared with the recent past, and there are fewer calm days. For hunters out in small boats, even a 10 to 12 mph wind creates waves of sufficient size to swamp boats (see Chapter 3 (Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic)). Winds also affect distribution of sea ice. Early season strong winds move sea ice northward and the marine mammals on the retreating ice are quickly out of range of some villages (notably those on St. Lawrence and Diomede Islands, and Shishmaref). Winds can also pack sea ice so tightly against shorelines that hunters are unable to get their boats out. These changes are not predictable, which affects both hunting opportunity and safety. For example, in spring 2001 Barrow whalers made trails at least 50 miles long through the shore ice to reach open leads for hunting. In spring 2002, hunters out on the ice edge became stranded as a large lead unexpectedly developed between their hunting camp and the shore, necessitating a major rescue effort.

Marine mammals are an integral part of the culture and economy of indigenous communities in Alaska, as they have been for centuries. Indigenous people depend on marine mammal species for food and other subsistence needs and utilize all species that are available within Alaskan waters to some degree. The United States is a participant in the 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears and the 2000 U.S./Russia Bilateral Agreement on the Conservation and Management of the Alaska–Chukotka Polar Bear Population. The Alaskan Department of Fish and Game is the state authority dealing with management issues related to polar bears. However, national responsibility for polar bears remains under legislation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. Polar bears can be harvested for subsistence purposes or for creating items of handicraft or clothing by coastal dwelling indigenous people provided that the populations are not depleted and the taking is not wasteful. There are no limits on quotas, seasons, or other aspects of the hunt. No commercial hunting or sale of polar bears or their parts are permitted[59]. Polar bear stocks in Alaska are linked to the east (Southern Beaufort Sea stock) with Canada and to the west (Chukchi/Bering Sea stock) with Russia. A joint agreement exists between the Inuvialuit Game Council, NWT and the Iñupiaq of the North Slope Borough, Alaska for the management of the Southern Beaufort Sea group and negotiations are near completion with Russia for the western areas. Polar bear catches in Alaska vary annually, depending largely on how many bears approach areas near settlements, because there is little targeted hunting effort on this species. The number of bears shot annually in the 1990s varied between approximately 60 and 300. There is no indication that the current level of hunting is not sustainable, although information is lacking for the Chukchi/Bering Sea stock[60].

In 1994, an amendment to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 included provisions for the development of cooperative management agreements between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Alaska Native organizations to conserve marine mammals and provide for the co-management of subsistence use by Alaskan indigenous people. A mandatory marking, tagging, and reporting program implemented by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1988 for some species has provided considerable data for subsistence harvests in recent years. The Indigenous People’s Council for Marine Mammals, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Biological Resources Division, and the National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service jointly administer co-management funds provided to the State of Alaska under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service works with a number of groups to manage marine mammals in Alaska such as the Alaska Sea Otter and Steller Sea Lion Commission, the Alaska Nanuuq Commission, and the Eskimo Walrus Commission. For example, the Cooperative Agreement developed in 1997 between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Eskimo Walrus Commission has served to facilitate the participation of subsistence hunters in activities related to the conservation and management of walrus stocks in Alaska. The agreement has resulted in the strengthening and expansion of harvest monitoring programs in Alaska and Chukotka, as well as efforts to develop locally based subsistence harvest regulations. The mean annual harvest of Pacific walrus over the period 1996 to 2000 was about 5,800 animals. However, the hunt has varied quite dramatically from year to year depending primarily on ice conditions and hunting effort, and has varied between 4,000 and 16,000 animals per year over the 1980s and 1990s[61]. Sustainable level of harvest cannot be prescribed because of a lack of information on population size and trend, but the population is thought to number in excess of 200,000 animals, having recovered dramatically from heavy exploitation early in the 20th century. Other seals, such as ringed seals, bearded seals, harbour seals, and spotted seals (Phoca largha) are important in the diet of indigenous people in Alaska and are harvested in significant numbers.

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) were heavily depleted by commercial harvests during the 1700s, and probably numbered only a few thousand animals in 13 remnant colonies when they became protected by the International Fur Seal Treaty in 1911[62]. Following protection and translocation of animals, they recovered and re-colonized much of their historic range in Alaska. Sea otter populations in southcentral Alaska and those reintroduced into southeast Alaska are growing and each of the two stocks is subject to a subsistence harvest of about 300 animals. The southwestern Alaskan stock in the Aleutian Islands is undergoing a population decline that is not explained by the level of human-induced mortality. Heavy predation by killer whales, previously not known to be a significant predator on sea otters, has been reported and postulated as a cause for the decline[63]. This apparent shift in trophic level relationships is also thought to be tied to other changes brought about through heavy commercial fishing pressure and warming of these marine waters through strong El Niño events and climate warming[64].

The northern fur seal historically underwent population reductions through heavy commercial harvests both at breeding colonies and at sea. It then was managed by international treaty through the North Pacific Fur Seal Commission. Commercial hunting of this species was terminated in 1985. However, like the sea otter in the west and several other marine mammal populations including Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus)[65] and harbour seals[66], the fur seal has been declining since about 1990 at a rate of 2% per year[67] despite small subsistence harvests. The current marine mammal population declines in the Bering Sea and North Pacific appear to be part of a complex regime shift that is thought to be the result of temperature shifts that caused several major fish stocks to collapse and the impacts are cascading through the system (e.g., [68]). The collapse of these fish stocks, however, may be tied to the intense commercial exploitation of the Bering and North Pacific fisheries. Management responses to the population declines have been undertaken through a host of plans and agreements, such as the Co-management Agreement between the Aleut community of St. George Island and the National Marine Fisheries Service that was signed in 2001 to address management of the northern fur seal and Steller sea lion at St. George Island[69].

Fig. 11.15. The bowhead whale harvest at Barrow, Alaska is carried out under a regional harvest quota established by the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission. (Source: Photograph by the Department of Wildlife Management, North Slope Borough)

Fig. 11.15. The bowhead whale harvest at Barrow, Alaska is carried out under a regional harvest quota established by the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission. (Source: Photograph by the Department of Wildlife Management, North Slope Borough) Subsistence hunting of bowhead, gray, beluga, and minke whales takes place in Alaska (Fig. 11.15). At the local level the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission regulates whaling activities. Eskimo whaling is conducted from nine traditional whaling communities. The current quota of 51 bowhead whales is hunted from St. Lawrence Island and Little Diomede Island in the Bering Sea and from coastal villages along the northern Alaskan coast. This hunt was not sanctioned by the International Whaling Commission in 2002[70], however, an emergency session of the commission in 2003 agreed on a new quota for the Alaskan subsistence harvest. The bowhead is classified as an endangered species. The beluga is the second most important cetacean species harvested for subsistence in Alaska and it is hunted in significant numbers. The Alaska Beluga Whale Committee oversees this hunt. The gray whale quota, which is sanctioned by the International Whaling Commission, is 140 animals per year in the eastern North Pacific (620 animals from 2003 to 2006). This species was removed from the endangered species list in 1995 following a dramatic recovery in the eastern Pacific; western Pacific stocks (off Korea) have not recovered and remain listed. Minke whales are opportunistically taken in Alaska.

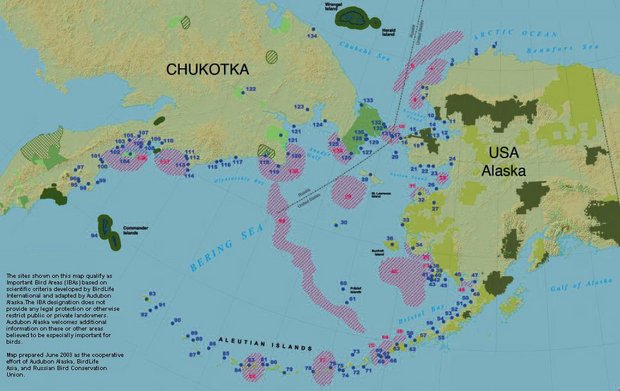

Fig. 11.16. Important Bird Areas in the Bering and Chukchi Sea regions. These have been generated through cooperative efforts of scientists in government agencies and non-governmental organizations, working with indigenous people and other coastal residents in Russia and the United States. The map is an essential step in the planning for a network of protected areas critical for the conservation of seabirds and their habitats in the Bering–Chukchi region. (Source: Map supplied by the National Audubon Society)

Fig. 11.16. Important Bird Areas in the Bering and Chukchi Sea regions. These have been generated through cooperative efforts of scientists in government agencies and non-governmental organizations, working with indigenous people and other coastal residents in Russia and the United States. The map is an essential step in the planning for a network of protected areas critical for the conservation of seabirds and their habitats in the Bering–Chukchi region. (Source: Map supplied by the National Audubon Society) Seabird harvests in Alaska are managed through a co-management council that includes indigenous, federal, and State of Alaska representatives that provide recommendations to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and North American Flyway Councils. The latter bodies are included because most harvested species fall under the North American Migratory Bird Treaty Act that prohibits hunting from 10 March until 1 September, but provisions for Alaska provide that indigenous inhabitants of the State of Alaska may harvest migratory birds and their eggs for subsistence uses at any time as long as there is no wasteful taking of birds or eggs. Seabirds and their eggs cannot be bought or sold in Alaska. Subsistence harvest information is only available for the last decade, and these statistics are thought to represent minimal harvest estimates. The two most harvested species are crested auklet (Aethia cristatella) (about 12,000) and common murre (about 10,000)[71]. Smaller numbers of other seabirds taken include: cormorants, gulls, common loons (Gavia immer), red-legged kittiwakes (Rissa brevirostris), black-legged kittiwakes, yellow-billed loons (G. adamsii), thick-billed murres, least auklets (Aethia pusilla), parakeet auklets (A. psittacula), Pacific loons (G. pacifica), Arctic loons (G. arctica), red-throated loons (G. stellata), ancient murrelets (Synthliboramphus antiquus), tufted puffins, Arctic terns, and horned puffins. Harvests from St. Lawrence Island communities dominate the overall harvest statistics. The ten-year average for eider harvests are common eider 2,000, king eider (Somateria spectabilis) 5,500, spectacled eider (S. fischeri) 200, and Steller’s eider (Polysticta stelleri) 50. Seabird egg collecting is more evenly spread geographically than the hunting of birds, with eggs of gulls, murres, and terns being the most commonly harvested[72]. More information is needed on population trends and the harvests themselves as a basis for establishing sustainable harvest levels. Harvest by humans, however, is not recognized by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a threat to seabirds in Alaska[73]. Recommendations for regulations governing harvest of game and non-game birds for each season are adopted by the Co-management Council and then forwarded to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for action. These include seasons, bag limits, restrictions on methods for taking birds, law enforcement policies, and recommendations for programs to monitor populations, provide education for the public, assist integration of traditional knowledge, and instigate habitat protection[74].

A new conservation tool for seabirds and their habitats is Important Bird Areas (IBAs). The program was started in Europe in 1989 by Birdlife International and has grown into a worldwide wildlife conservation initiative. The goal of the IBA program is to get indigenous people, landowners, scientists, government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and land trusts to work together and set priorities for bird conservation. There are criteria regarding high concentration areas and rare species that are considered for inclusion into the IBA program. In Alaska, Audubon Alaska has recently completed a draft list of IBAs for the Bering and Chukchi Seas. While IBAs are for all birds, the ones identified in Alaska were mostly set up because of high concentrations of seabirds. There are 138 sites, the majority of which are in the Bering Sea (Fig. 11.16).

Future strategies (11.4.5)

A changing environment will result in changes in subsistence hunting patterns. Harvest levels may decrease for some species as their seasonal availability decreases, while for others, harvest levels may increase. Close documentation of harvest levels and patterns will be needed to track these changes and to contribute to site-specific information on wide-ranging species. Hunter participation in collection of population and other biological information is essential for effective marine mammal management. Changes in health of walrus were reported in 2000, when hunters reported that adults appeared skinny and that few calves were present, potentially reflecting poor access to food resources. For ice-dependent species that are difficult to study directly, information from subsistence-harvested animals can be of considerable value for their management. In addition, hunters are interested in and concerned about changes they are observing. Should harvest restrictions become necessary, direct involvement of the subsistence community in developing the restrictions will facilitate such changes.

Marine mammals, throughout most of the Arctic, are the primary subsistence food base for coastal residents of the Arctic. Seabirds, including eiders and other sea ducks, alcids, and gulls, are also important to many coastal communities as a source of food. In some areas seabirds are also harvested commercially. The most productive regions for seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere are between approximately 50° and 70° N. Well over 100 million seabirds live in these arctic and subarctic regions, an order of magnitude more than seabirds living in the temperate regions[75]. The management implications of climate change are complicated and largely unknown, but increasing [[temperature]s], thawing of the sea ice with associated movement of the pack ice edge northward, and rising sea levels will certainly reduce the availability of seabirds as food to many arctic communities. This will complicate the role of management to ensure the health of seabird populations as components of ecosystems undergoing change, while providing for the sustainable use of the seabirds by the people that depend upon them. A further complication in assessing how seabirds may move northward and possibly establish new nesting colonies within the context of a warmer climate is the difficulty of predicting how the marine food species upon which seabirds are dependent may change their distribution and productivity in relation to climate change and other human impacts such as commercial fisheries.

North Pacific, Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas (11.4.5.1)

If [[temperature]s] increase for sustained periods, with associated melting of Arctic Ocean ice, and the band of high seabird productivity shifts northward, there is likely to be a dramatic overall decline in the number of seabirds living in the arctic and subarctic regions of the North Pacific and adjacent Arctic Ocean where high-latitude nesting islands are extremely limited. This is particularly apparent when contrasting the rugged island and coastal topography of the southern Bering Sea with the low-lying coastal plains that border much of the northern Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. A different situation exists in the North Atlantic and Canadian High Arctic because of more high latitude islands with rugged coastal topography that might serve as new nesting sites. In addition, if the sea level rises as projected as a consequence of climate warming, many low-elevation nesting islands used by eiders, terns, and gulls will be inundated, resulting in decreased numbers of these species.

Estimates of population trends and status, current management, and threats for arctic seabirds of the North Pacific and associated Arctic Ocean, including the Bering, Okhotsk, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas, are summarized in Table 11.6. Presently there is little or no information on population trends of many seabird species nesting in the Arctic. Better data on population trends are critical for effective management and conservation of these species, especially in areas where they are harvested for human use.

|

Table 11.6. Population trends, management, and threats to marine birds in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. | |||||||

|

Population trends: Bering Sea |

Population trends: Beaufort and Chukchi Seas |

Management regulationsa |

Harvest birds |

Harvest eggs |

Threatsb |

Statusc | |

| Common loon | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 | 3 |

| Yellow-billed loon | Unknown | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 | 2 |

| Pacific loon | Stable | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 | 3 |

| Arctic loon | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 | 3 |

| Red-throated loon | Decrease | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 | 2 |

| Short-tailed albatross | Increase | N/A | Yes | No | No | 3,5,6,7 | 1 |

| Black-footed albatross | Decrease | N/A | Yes | No | No | 3,5,6,7 | 2 |

| Laysan albatross | Decrease | N/A | Yes | No | No | 3,5,6,7 | 2 |

| Northern fulmar | Increase | N/A | Yes | No | No | 3,7 | 3 |

| Fork-tailed storm petrel | Increase | N/A | Yes | No | No | 3,7 | 3 |

| Double-crested cormorant | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,3,7 | 3 |

| Pelagic cormorant | Decrease | Unknown | Yes | Yes | No | 1,3,7 | 3 |

| Red-faced cormorant | Unknown | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,3,7 | 2 |

| Common eider | Stable | Decrease | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,3,6,7 | 3 |

| King eider | N/A | Decrease | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,3,6,7 | 2 |

| Spectacled eider | Stable | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,2,3,6,7 | 1 |

| Steller’s eider | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 | 1 |

| Herring gull | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | Probable | 7 | 3 |

| Glaucous-winged gull | Decrease | N/A | Yes | Probable | Yes | 7 | 3 |

| Glaucous gull | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Probable | Yes | 7 | 3 |

| Red-legged kittiwake | Decrease | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 | 2 |

| Black-legged kittiwake | Decrease | Increase | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 | 3 |

| Arctic tern | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4,7 | 2 |

| Aleutian tern | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | No | Yes | 4,7 | 2 |

| Common murre | Decrease | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,3,7 | 3 |

| Thick-billed murre | Stable | Stable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,3,7 | 3 |

| Black guillemot | N/A | Decrease | Yes | No | No | 1,7 | 3 |

| Pigeon guillemot | Unknown | N/A | Yes | Yes | No | 1,3,6,7 | 3 |

| Marbled murrelet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,3,4,5,7 | 2 |

| Kittlitz’s murrelet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,3,4,7 | 2 |

| Ancient murrelet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,7 | 2 |

| Cassin’s auklet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,7 | 3 |

| Parakeet auklet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,7 | 3 |

| Crested auklet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | Yes | No | 1,7 | 3 |

| Whiskered auklet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | No | No | 1,7 | 2 |

| Least auklet | Unknown | N/A | Yes | Yes | No | 1,7 | 3 |

| Horned puffin | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Probable | 1,7 | 3 |

| Tufted puffin | Increase | N/A | Yes | Yes | Probable | 1,3,7 | 3 |

| N/A not applicable; aRegulated within the 3 nautical mile territorial waters zone by the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act; b1: oil pollution, 2: over-harvest, 3: fisheries by-catch, 4: human disturbance, 5: habitat alteration, 6: contaminants, 7: climate change; c1: Threatened or Endangered (U.S.), 2: Birds of Conservation Concern (U.S.), 3: Low or moderate concern. | |||||||

Chapter 11. Management and Conservation of Wildlife in a Changing Arctic Environment

11.1 Introduction (Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic)

11.2 Management and conservation of wildlife in the Arctic

11.3 Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management

11.3.1 Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic

11.3.2 The Canadian North

11.3.3 The Fennoscandian North

11.3.4 The Alaskan Arctic

11.4 Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic

11.5 Critical elements of wildlife management in an Arctic undergoing change

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Management_and_conservation_of_marine_mammals_and_seabirds_in_the_Arctic- ↑ Donovan, G.P. (ed.), 1982. Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 4.–Kinloch, D., H. Kuhnlein and D.C.G. Muir, 1992. Inuit foods and diet: a preliminary assessment of benefits and risks. Science of the Total Environment, 122:247–278.–Pars, T., M. Osler and P. Bjerregaard, 2001. Contemporary use of traditional and imported food among Greenlandic Inuit. Arctic, 54(1):22–31.–Riewe, R.R. and L. Gamble, 1988. The Inuit and wildlife management today. In: M.M.R. Freeman and L.N. Carbyn (eds.). Traditional Knowledge and Renewable Resources Management in Northern Regions, pp. 31–37. Boreal Institute for Northern Studies.

- ↑ Newton, J., 2001. Background document to Climate Change Policy Options in Northern Canada. John Newton Associates.–Riedlinger, D., 1999. Climate change and the Inuvialuit of Banks Island, NWT: using traditional environmental knowledge to complement western science. Arctic, 52(4):430–432.–Riedlinger, D., 2002. Responding to climate change in northern communities: impacts and adaptations. Arctic, 54(1):96–98.–Weller, G., P. Anderson and B. Wang (eds.), 1999. Preparing for a Changing Climate: The Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change. A report of the Alaska Regional Assessment group prepared for the U.S. Global Change Research Program. Center for Global Change and Arctic System Research, Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Wiig, Ø, E.W. Born and G.W. Garner (eds.), 1995. Polar Bears: Proceedings of the Eleventh Working Meeting of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, January 25–29 1993. v + 192pp.

- ↑ USFWS, 1997. Final Environmental Assessment - Development of Proposed Treaty US/Russian Bilateral Agreement for the Conservation of Polar Bears in the Chukchi/Bering Seas. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.–USFWS, 2002a. Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus): Chukchi/Bering Sea Stock. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ CAFF, 1996. International Murre Conservation Strategy and Action Plan. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Reykjavik.

- ↑ CAFF, 1997. Circumpolar Eider Conservation Strategy and Action Plan. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Reykjavik.

- ↑ AMAP, 1998b. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme. Hydrometeoizdat. St. Petersburg, 188pp.–Yablokov, A.A. (ed.), 1996. Russian Arctic: On the Edge of Catastrophe. The Centre of Ecological Politics of Russia, Moscow, 207pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Dinesman, L.G., N.K. Kiseleva, A.B. Savinetsky and B.F. Khassanov, 1996. Secular Dynamics of Coastal One of Northeastern Chukotka. Argus, Moscow, 189pp.

- ↑ Bogoslovskaya, L.S., 2003. pers. obs. Center of Traditional Subsistence Studies, Russian Research Institute of Cultural and Natural Heritage, Moscow.

- ↑ Melnikov, S.A., C.V. Vlasov, O.V. Rishov, A.N. Gorshkov and A.I. Kuzin, 1994. Zones of relatively enhanced contamination levels in the Russian Arctic Seas. Arctic Research of the United States, 18:277–283.

- ↑ Yablokov, A.A. (ed.), 1996. Russian Arctic: On the Edge of Catastrophe. The Centre of Ecological Politics of Russia, Moscow, 207pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Belikov, S.E., 1993. Status of polar bear populations in the Russian Arctic 1993. In: Ø. Wiig, E.W. Born and G.W. Garner (eds.). Polar Bears: Proceedings of the Eleventh Working Meeting of the IUCN/SC Polar Bear Specialist Group, pp. 115–120. The World Conservation Union

- ↑ USFWS, 1997. Final Environmental Assessment - Development of Proposed Treaty US/Russian Bilateral Agreement for the Conservation of Polar Bears in the Chukchi/Bering Seas. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.–USFWS, 2002a. Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus): Chukchi/Bering Sea Stock. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ Government of the Russian Federation, 2001. Government of the Russian Federation Decree 20 November 2001 #1551-p. To approve enclosed Limits of Total Allowed Catches of aquatic biological resources in internal marine waters, in territorial waters, on continental shelf and in exclusive economic zone of the Russian Federation in 2002. Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, M. Kasianov.