Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic

Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic

This is part of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment Lead Author: David R. Klein; Contributing Authors: Leonid M. Baskin, Lyudmila S. Bogoslovskaya, Kjell Danell, Anne Gunn, David B. Irons, Gary P. Kofinas, Kit M. Kovacs, Margarita Magomedova, Rosa H. Meehan, Don E. Russell, Patrick Valkenburg

Hunting is an important part of the Russian economy, both through harvest of wildlife products and through pursuit of traditional sport and subsistence hunting. Fur production has been an essential part of the economy of the Russian North throughout history. Management of wildlife also has a long history in Russia, from early commercial and sport hunting to the creation of a complicated multifunctional state system under the Soviet government. Early attempts at regulation of hunting are known from the 11th century, and these attempts at wildlife management were connected with protection of species or groups of species. The first national law regarding hunting was imposed in 1892 as a reaction to widespread sport hunting, the establishment of hunter’s unions, and the efforts of naturalists and others with interests in wildlife. These early efforts toward managing wildlife were based on wildlife as a component of private property.

Under the Soviet system, wildlife management developed on the basis of state ownership of all resources of the land, including wildlife, and a state monopoly over foreign trade and fur purchasing. Commercial hunting was developed as an important branch of production within the national economy. The state-controlled wildlife management system resulted in an elaborate complex of laws as the basis for governing commercial and sport hunting, for investigation of resources and wildlife habitats, for organization of hunting farms or collectives, for establishment of special scientific institutes and laboratories, for incorporation of scientific findings in wildlife management, and for the development of a system of protected natural areas. Justification for identifying natural areas deserving protection in the Russian Arctic became apparent as major segments of the Russian economy increased their dependence on exploitation of arctic resources during the Soviet period, stimulated by the knowledge that 70 to 90% of the known mineral resources of the country were concentrated in the Russian North[1]. More than 300 protected natural areas of varying status were established for restoration and conservation of wildlife resources in the Russian Far North[2].

Wildlife management was concentrated in a special Department of Commercial Hunting and Protected Areas within the Ministry of Agriculture. Local departments were organized in all regions of the Russian Federation for organization, regulation, and control of hunting with the intent to make them appropriate for actual conditions. Hunting seasons were established for commercial and sport hunting by species, regulation of numbers harvested, and designation of types of hunting and trapping equipment to be used. The major hunting activity was concentrated in specialized hunting farms. Their organization was initially associated with designated areas. The main tasks of the state hunting farms were planning, practical organization of hunting, and management for sustained production of the wildlife resources. At the same time, the system of unions of sport hunters and fishers was organized for regulation of sport hunting and fishing under the control of the Department of Commercial Hunting and Protected Areas[3].

Commercial hunting has been primarily concentrated in the Russian Far North (tundra, forest–tundra, northern taiga), which makes up 64% of the total hunting area of the Russian Federation. During the latter decades of the Soviet system the Russian Far North produced 52% of the fur and 58% of the meat of ungulates and other wildlife harvested. The proportional economic value of the three types of resident wildlife harvested was 41% for fur (sable (Martes zibellina) – 50%, arctic fox – 9%, ermine (Mustela erminea) – 18%), 40% for ungulates (moose – 41%, wild reindeer – 58%), and 19% for small game (ptarmigan (Lagopus spp.) – 68%, hazel grouse (Tetrastes bonasia) – 15%, wood grouse (Tetrao urogallus) – 11%)[4]. Variation by region in characteristics of the harvest of wildlife in the Russian Arctic and subarctic is compared in Table 11.1. Participation in commercial hunting by the able-bodied local population was 25 to 30%. Profit from hunting constituted 52 to 58% of the income of the indigenous population. Of the meat of wild ungulates harvested, the amount obtained per hunter per year was 233 kilograms (kg) for professional hunters, 143 kg for semi-professional hunters, and 16 kg for novice hunters. The proportion of total wild meat harvested that was purchased by the state was 60%. Of that purchased by the state, 73% was for consumption by the local population. Fish has also been an important food resource for local populations, as well as for the professional hunters/ fishers. A professional hunter’s family would use about 250 kg of fish per year, and 2,000 kg of fish were required per year to feed a single dog team (eight dogs). By the end of the 1980s state purchase of wildlife and fish was 34% of potential resources, and local consumption was 27%[5].

|

Table 11.1. Regional variation in wildlife harvest in the Russian Arctic and subarctic under the Soviet system[6]. | ||||

|

European |

Western |

Eastern |

Northern Far | |

| Share of area (%) | 7 | 14 | 25 | 54 |

| Ranking of relative biological productivity | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Proportion of available resource harvested (%) | 23 | 48 | 76 | 63 |

| Expenditure (%) | 9 | 15 | 34 | 4 |

| Breakdown of value by species within region | ||||

| Fur | ||||

| Sable (%) | – | 14 | 24 | 23 |

| Polar fox (%) | 5 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Ungulate | ||||

| Moose (%) | 15 | 18 | 12 | 20 |

| Wild reindeer (%) | 4 | 8 | 42 | 15 |

| Game | ||||

| Partridge (%) | 51 | 26 | 4 | 8 |

| Distribution of the harvest | ||||

| Purchased by the state (%) | 33 | 37 | 61 | 58 |

| Local consumption (%) | 67 | 63 | 39 | 42 |

Indigenous residents of the Russian Arctic and subarctic have not had limitations on hunting for their subsistence use. However, all those engaged in professional, semi-professional, and sport hunting have been required to purchase licenses. Indigenous people involved in the state-organized hunting system were also provided with tools and consumer goods. The main problems that have confronted effective wildlife management in the Russian Arctic are widespread poaching, uneven harvest of wildlife, and loss of wildlife habitats and harvestable populations in connection with industrial development.

The wildlife management system in the Russian Arctic was not destroyed by the transformation of the political and economic systems that took place at the end of the 20th century, but it was weakened. Partly as a consequence of this weakening, but also due to expansion of industrial development in the Russian Arctic and the effects of climate change, there has been the development of several major threats to effective wildlife conservation.

- Transformation of habitats in connection with industrial development. From an ecological standpoint the consequences of industrial development affect biological diversity, productivity, and natural dynamics of ecosystems. As far as environmental conditions are concerned it is important to note that apart from air and water pollution there is a possibility of food pollution. In terms of reindeer breeding, hunting, and fishing, industrial development has resulted in loss of habitats and resources, a decrease in their quality and biodiversity, and destruction of grazing systems[7]. A considerable portion of the biological resources presently exploited is from populations outside regions under industrial development[8].

- Reduction in wildlife populations as a result of unsystematic and uncontrolled exploitation through commercial hunting.

- Curtailment of wildlife inventory and scientific research, resulting in loss of information on population dynamics, health, and harvest of wildlife.

- Changes in habitat use by wildlife, in migration routes, and in structure and composition of plant and animal communities as a consequence of climate change. Such changes include increased frequency and extent of fires in the northern taiga, displacement northward of active breeding dens of the Arctic fox on the Yamal Peninsula[9], as well as in other areas[10], and replacement of arctic species by boreal species as has occurred in the northern part of the Ob Basin[11].

Both commercial and sport hunting are permitted throughout the Russian North. Commercial hunting for wild reindeer for harvest of velvet antlers is permitted for 20 days in the latter part of June. Commercial hunting of reindeer for meat can take place from the beginning of August through February. Sport hunting is permitted from 1 September to 28 February. A license is required to hunt reindeer (cost for sportsmen about US$4, for commercial enterprise about US$3).There are no restrictions on numbers of reindeer to be hunted. Hunting is permitted everywhere, with the exception of nature reserves. Regional wildlife harvest systems are compared in Table 11.2, together with associated wildlife population trends, threats to wildlife and their habitats, and conservation efforts.

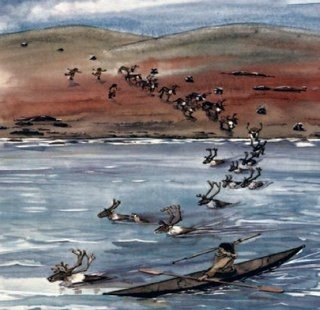

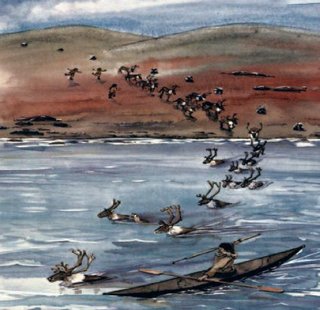

Figure 11.3. Harvesting by indigenous people of wild reindeer in the Russian North and caribou in North America was traditionally done at river crossings on migration routes. This continues to be an efficient method of hunting reindeer and caribou in some regions, a hunting system that lends itself to managed control of the harvest. (Source: ACIA)

Figure 11.3. Harvesting by indigenous people of wild reindeer in the Russian North and caribou in North America was traditionally done at river crossings on migration routes. This continues to be an efficient method of hunting reindeer and caribou in some regions, a hunting system that lends itself to managed control of the harvest. (Source: ACIA) In recent years in the Russian North, marketing of venison experienced an economic revival. In mining settlements in 2001 the cost of venison commonly approached US$2.5 per kilogram, making commercial hunting of reindeer potentially profitable. A significant demand has also existed for velvet antlers. However, under existing conditions in most of the Russian North where there are no roads and settlements are few, hunting of wild reindeer at river crossings remains the most reliable and productive method of harvest. (see the case study on river crossings as focal points for wild reindeer management in the Russian Arctic in Box 11.3) Additionally, concentration of hunting effort at specific river-crossing sites provides an opportunity to influence hunting methods and for monitoring the number of animals killed. A proposal has been made to protect the traditional rights of indigenous hunters by granting them community ownership of some of the reindeer river crossings. This would presumably allow them to limit increasing competition from urban hunters for the reindeer. At present, indigenous people hunt reindeer only for their personal or community needs, but as owners of reindeer harvest sites at river crossings they would have a basis for developing a commercial harvest. Some large industrial companies have indicated a readiness to support commercial harvest of reindeer by indigenous people by assisting in the transportation of harvested reindeer to cities and mining settlements. Already, there are plans to open some of the more accessible river crossings for hunting by people from nearby towns and this will include personal use as well as commercial sale of the harvested reindeer. However, there is a need for development of regulations to prevent excessive harvesting of the reindeer and associated alteration of their migration routes. The inability in the past to predict the availability over extended periods of time of wild reindeer for human harvest because of their natural long-term population fluctuations led many indigenous peoples in the Arctic to include more than one ecologically distinct resource (e.g., reindeer and fish) as their primary food base. Similarly, a balance between harvest of reindeer for local consumption and commercial sale in communities in the Russian North would appear to offer greater flexibility for management of the reindeer and sustainability of local economies than large-scale commercial harvesting of reindeer. Flexibility in options for management of wild reindeer will be essential in the Arctic of the future that is expected to experience unpredictable and regionally variable ecological consequences of climate change. Increased adaptability of the arctic residents to climate change will be best achieved through dependence on a diverse resource base. This applies to the monetary and subsistence economies of arctic residents, as well as to the species of wildlife targeted for management, if wildlife is to remain an essential base for community sustainability.

|

Box 11.3. River crossings as focal points for wild reindeer management in the Russian Arctic Harvesting wild reindeer at river crossing sites (see Fig. 11.3) has played a significant role in regional economies and the associated hunting cultures in the Russian North[12]. Many crossing sites were the private possession of families[13]. When reindeer changed crossing points it sometimes led to severe famine, and entire settlements vanished[14]. Such changes in use of migration routes are thought to result from fluctuations in herd size and interannual climate variability. Under the Soviet government, large-scale commercial hunting at river crossings displaced indigenous hunters. Importance of river crossings for wild reindeer harvest On the Kola Peninsula and in western Siberia there are few known locations for hunting reindeer at river crossings. In Chukotka, a well-known place for hunting reindeer was located on the Anadyr River at the confluence with Tahnarurer River. In autumn, reindeer migrated from the tundra to the mountain taiga and hunters waited for them on the southern bank of the Anadyr River. Reindeer often select different routes when migrating from the summering grounds. Indigenous communities traditionally arranged for reconnaissance to try to predict the migration routes. In Chukotka, mass killing sites at river crossings were known only in the tundra and forest–tundra, not in the taiga[15]. In Yakutia, reindeer spend summers on the Lena Delta where forage is abundant and cool winds, and the associated absence of harassment by insects, provide favorable conditions for reindeer. In August–September, as the reindeer migrate southwestward, hunters wait and watch for them on the slightly elevated western bank of the Olenekskaya Protoka channel of the Lena Delta where the reindeer traditionally swim across the channel. In the Taymir, 24 sites for hunting reindeer by indigenous people were located along the Pyasina River and its tributaries[16].The killing sites at river crossings occupy fairly long sections of the river. In more recent times when commercial slaughtering occurred, hunter teams occupied sections 10 to 20 kilometers long along the river and used observers to signal one another by radio about approaching reindeer; motor boats carrying the hunters then moved to points on the river where hunting could take place[17]. In the more distant past, hunters used canoes and needed to be more precise in determining sites and times of the reindeer crossing. Reindeer are very vulnerable in water, and although their speed in water is about 5.5 km/hr[18] humans in light boats could overtake the animals. In modern times, using motorboats and rifles, hunters were able to kill up to 70% of the animals attempting to cross the rivers at specific sites. A special effort was made to avoid killing the first reindeer entering the water among groups approaching the river crossings. Experience showed that if the leading animals were shot or disturbed those following would be deflected from the crossing. Conversely, if the leading animals were allowed to cross, following animals continued to cross despite disturbance by hunting activities[19]. Commercial harvest at river crossings During the Soviet period, large-scale commercial harvest of reindeer at river crossings displaced indigenous hunters from these traditional hunting sites[20]. In Yakutia, after commercial hunting began in the 1970s, hunting techniques included the use of electric shocks to kill reindeer as they came out of the water. In recent years these commercially harvested reindeer populations in Yakutia declined precipitously[21]. In the Taymir, indigenous people practiced subsistence hunting at river crossings until the 1960s. However, by 1970, hunting regulations had banned hunting at river crossings by indigenous people and other local residents because of concern that over-harvest of the reindeer would occur.The Taymir reindeer increased greatly in the following years. Biologists working with the reindeer proposed reinstatement of the traditional method of killing animals at river crossings in order to establish a commercial harvest from the large Taymir population and to stabilize the population in line with the carrying capacity of the available habitat. The Taymir state game husbandry system was established by 1970. Up to 500 hunters participated in the annual harvests. All appropriate river hunting locations on the Pyasina River and the Dudypta, Agapa, and Pura tributaries were taken over for the commercial harvests. Large helicopters and in some cases refrigerated river barges were used to transport reindeer carcasses to markets in communities associated with the Norilsk industrial complex. Over a period of 25 years about 1.5 million reindeer were harvested by this system[22]. After 1992, there was a decrease in the number of reindeer arriving at most of these river crossings, resulting in an abrupt decline in the harvest from about 90000 per year in peak years to about 15000 per year in subsequent years. This was associated with the disproportionate harvest of female reindeer[23]. Consequences of climate change Climate change may affect river crossings as sites for controlled harvest of reindeer in several ways. If patterns of use of summering areas change in relation to climate-induced changes in plant community structure and plant phenology then migratory routes between summer and winter ranges may also change.Thus, some traditional crossings may be abandoned and new crossings established. Changes in the timing of freeze-up of the rivers in autumn at crossing sites may interfere with successful crossings by the reindeer if the ice that is forming will not support the reindeer attempting to cross.These conditions have occurred infrequently in the past in association with aberrant weather patterns; however timing of migratory movements would also be expected to change with a consistent directional trend mirroring seasonal events. |

Changes have occurred over time in methods and patterns of harvesting wild reindeer in the Russian North and these changes provide perspective on wildlife management in a changing climate. Since prehistoric times indigenous peoples throughout Eurasia and North America have hunted wild reindeer and caribou during their autumn migration at traditional river crossings. Boats were used to intercept the swimming animals where they were killed with spears (Fig. 11.3). This method of harvesting wild reindeer may offer potential for management of wild reindeer under the recent drastic changes that have taken place in social and economic conditions among the indigenous peoples of the Russian North resulting from the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Can management of wild reindeer through harvesting primarily at river crossings ensure sustainable harvests from the large migratory herds under conditions of human social and economic change compounded by the effects of climate change on the reindeer and their habitats? Addressing this question may be possible by comparing the population dynamics of reindeer and caribou herds in regions of the Arctic with differing climate change trends[24][25].

|

Table 11.2. Comparison of wildlife harvest systems in the Russian North. | |||

|

Harvest system |

Wildlife population trends | Threats to wildlife and their habitats | Conservation efforts |

|

Kola Peninsula | |||

| Hunting for subsistence and for local market sales | Over-harvest of ungulates, drastic decline in wild reindeer |

Over-harvest of ungulates by military and for subsistence, fracturing of habitats by roads and railroads, habitat degradation from industrial pollution |

Laplandsky Reserve (1930) 2,784 km2, Pasvik Reserve (1992) 146 km2 (International, with Norway’s Oevre Pasvik Park 66.6 km2) |

|

Nenetsky Okrug,Yamal, Gydan | |||

|

Intensive reindeer husbandry, control of large predators, incidental subsistence hunting, Arctic fox trapping |

Decline in wolves, wolverines, and foxes | Over-grazing by reindeer, habitat damage by massive petroleum development with roads and pipelines, hunting by workers, control of predators | Nenetsky Reserve (1997) 3,134 km2 (near Pechora delta – waterfowl and marine mammals) |

|

Khanty-Mansiysky Okrug | |||

|

Hunting focus on wild reindeer, moose, and furbearers; indigenous hunting culture in decline |

Low hunting pressure, populations stable | Industrial development, forest and habitat destruction, fragmentation by roads and pipelines, pollution from pipeline leaks | Reserves: Malaya Sosva 2,256 km2, Gydansky 8,782 km2, Yugansky 6,487 km2, Verkhne-Tazovsky 6,133 km2 |

|

Taymir | |||

|

Hunting focus on wild reindeer and waterfowl, mostly subsistence, commercial harvest of velvet antlers at river crossings, restrictions limiting commercial antler harvest being enforced |

Decline or extirpation of wild reindeer subpopulations near Norilsk, inadequate survey methods | Wild reindeer total counts are basis for management; lack of knowledge of identity and status of discrete herds; extensive habitat loss from industrial pollution; habitat fracturing and obstructed movements by roads, railroad, pipelines, and year-round ship traffic in Yenisey River for metallurgical and diamond mining, and oil and gas production | Reserves: Putoransky 18,873 km2, Taimyrsky 17,819 km2, Bolshoy Arctichesky 41,692 km2; region-wide ecosystem/community sustainability plan being developed |

|

Evenkiya | |||

|

Hunting for subsistence and local markets, primarily moose, wild reindeer, and bear, little trapping effort |

Little information, assumed stable | Low human (Evenki) density and poor economy result in little threat at present to wildlife and habitats | Need is low due to remoteness and low population density. No nature reserves |

|

Yakutia (Sakha) | |||

|

Hunting primarily for wild reindeer, moose, snow sheep, and fur bearers, heavy commercial harvest as well as for subsistence, decline of reindeer herding increases dependency on subsistence hunting |

Heavy harvest of reindeer and snow sheep for market results in population declines, introduced muskox increasing | Diamond mining provides markets for meat leading to over-harvest and non-selective culling, decrease in sea ice restricts seasonal migrations of reindeer on Novosiberski Islands to and from mainland | Ust Lensky Reserve 14,330 km2. Muskox introduction adds new species to regional biodiversity and ecosystem level adjustments |

|

Chukotka | |||

|

Wild reindeer, snow sheep, and marine mammals hunted for subsistence by Chukchi and Yupik people |

Increases in wild reindeer, snow sheep, and large predators with decline in reindeer herding, muskoxen on Wrangel Island increasing | Major decline in reindeer herding, movement of Chukchi to the coasts, poor economy, and low extractive resource potential results in greatly reduced threats to wildlife inland from the coasts, increased pressure on marine mammals for subsistence | Reserves: Wrangel Island 22,256 km2, Magadansky 8,838 km2, Beringia International Park – proposed but little political support |

Chapter 11. Management and Conservation of Wildlife in a Changing Arctic Environment

11.1 Introduction (Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic)

11.2 Management and conservation of wildlife in the Arctic

11.3 Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management

11.3.1 Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic

11.3.2 The Canadian North

11.3.3 The Fennoscandian North

11.3.4 The Alaskan Arctic

11.4 Management and conservation of marine mammals and seabirds in the Arctic

11.5 Critical elements of wildlife management in an Arctic undergoing change

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2013). Climate change and terrestrial wildlife management in the Russian Arctic and sub-Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Russian_Arctic_and_sub-Arctic- ↑ Shapalin, B.F., 1990.The problems of economic and social development of the Soviet North. In: V.M. Kotlyakov and V.E Sokolov (eds.): Arctic Research. Advances and Prospects, pp. 415–419. Proceedings of the Conference of Arctic and Nordic Countries on Coordination of Research in the Arctic, Leningrad, December 1988. Part 2. Moscow: Nauka.

- ↑ Baskin, L.M., 1998. Hunting of game animals in the Soviet Union. In: E.J. Milner-Gulland and R. Mace (eds.). The Conservation of Biological Resources, pp. 331–345. Blackwell Science.

- ↑ Ammosov,V.A., N.N. Bakeev, A.T. Voilochnikov, M.P.Vorobjova, S.N. Grakov, V.N. Derjagin, I.P. Karpuhin, G.V. Korsakov, S.A. Korytin, S.A. Larin, S.V. Marakov, B.A. Mihailovskii, A.P. Nikulcev, M.P. Pavlov, E.V. Stahrovskii and J.P. Jazan, 1973. Commercial Hunting in USSR. Lesnaja promyshlennost, Moscow. 408pp. (In Russian)–Dezhkin, V.V. (ed.), 1978. Commercial Hunting in RSFSR. Lesnaja promyshlennost, Moscow, 256pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Zabrodin, V.A., A.M. Karelov and A.V. Dragan, 1989. Commercial Hunting in the Far North. Agropromizdat, Moscow, 204pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Zabrodin, V.A., A.M. Karelov and A.V. Dragan, 1989. Commercial Hunting in the Far North. Agropromizdat, Moscow, 204pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Zabrodin, V.A., A.M. Karelov and A.V. Dragan, 1989. Commercial Hunting in the Far North. Agropromizdat, Moscow, 204pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Dobrinsky, L.N. (ed.), 1995. Nature of Yamal. Nauka, Ekaterinburg, 435pp. (In Russian)–Dobrinsky, L.N. (ed.), 1997. Monitoring of the Biota at Yamal Peninsula in Relation to the Development of Facilities for Gas Extraction and Transportation. Ekaterinburg, 191pp. (In Russian)–Yablokov, A.A. (ed.), 1996. Russian Arctic: On the Edge of Catastrophe. The Centre of Ecological Politics of Russia, Moscow, 207pp. (In Russian)–Yurpalov, S.Y., V.G. Loginov, M.A. Magomedova and V.D. Bogdanov, 2001. Traditional economy in conditions of industrial expansion (as an example of Yamal-Nenets autonomous Okrug). UD RAN, Ekaterinburg, 36pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Yurpalov, S.Y., V.G. Loginov, M.A. Magomedova and V.D. Bogdanov, 2001. Traditional economy in conditions of industrial expansion (as an example of Yamal-Nenets autonomous Okrug). UD RAN, Ekaterinburg, 36pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Dobrinsky, L.N. (ed.), 1997. Monitoring of the Biota at Yamal Peninsula in Relation to the Development of Facilities for Gas Extraction and Transportation. Ekaterinburg, 191pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Yablokov, A.A. (ed.), 1996. Russian Arctic: On the Edge of Catastrophe. The Centre of Ecological Politics of Russia, Moscow, 207pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Yurpalov, S.Y., V.G. Loginov, M.A. Magomedova and V.D. Bogdanov, 2001. Traditional economy in conditions of industrial expansion (as an example of Yamal-Nenets autonomous Okrug). UD RAN, Ekaterinburg, 36pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Khlobystin, L., 1996. Eastern Siberia and Far East, Neolithic of Northern Eurasia. Arkheologiya, 3:270–329. (In Russian)

- ↑ Popov, A.A., 1948. Nganasany. Material culture. Akademiya Nauka Publ. 128pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Argentov, A., 1857. A description of the Nikolaevskiy Chaunskiy parish. -Zapiski Sibirskogo otdeleniya imperatorskogo Rossiskogo Geograficheskogo obshchestva, 111(1):70–101. (In Russian);-- Vdovin, I.S., 1965 Historical and ethnographic overview of Chukchi. Nauka Publ., 403pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Argentov, 1857, Op. cit.

- ↑ Popov, 1948, Op. cit

- ↑ (Sarkin, A.V., 1977. Establishing and economy of hunting and restoration of hunting resources in the state hunting husbandry ‘Taymyrskiy’. In: G.A. Sokolov (ed.). Ekologiya/ispol’zovanie okhotnich’ikh zhivotnykh Krasnoyarskogo kraya, pp. 84–88. Institut Lesa Publ. (In Russian)

- ↑ Michurin, L.N., 1965.Wild reindeer of the Taimyr Peninsula and rational utilization of its resources severnyi olen’Taymyrskogo poluostrova/ ratsional’naya utilizatsiya ego resursov.Thesis.Vsesoyuznyi sel’skokhozyaistvennyi institut zaochnogo obucheniya publ, Moscow. 24pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Savel’ev,V.D., 1977. Behavior of reindeer in river-crossings. In: G.A. Sokolov (ed.). Ekologiya/ispol’zovanie okhotnich’ikh zhivotnykh Krasnoyarskogo kraya, pp. 17–20. Institut Lesa Publ., (In Russian)

- ↑ Sarkin, 1977, Op. cit.;-- Zabrodin,V.A. and B.M. Pavlov, 1983. Status and rational use of Taimyr population of wild reindeer. In:V.E. Razmakhnin (ed.). Dikiy severnyiolen’. Ekologiya, voprosy okhrany/ratsional’nogo ispol’zovaniya, pp. 60–75.TSNIL Glavokhota Publ., Moscow. (In Russian)

- ↑ Safronov,V.M., I.S. Reshetnikov and A.K. Akhremenko, 1999. Reindeer of Yakutiya. Ecology, morphology and use. Nauka Publ., 222pp. (In Russian)

- ↑ Pavlov, B.M., L.A. Kolpashchikov and V.A. Zyryanov, 1993.Taimyr wild reindeer populations: management experiment. Rangifer, Special Issue 9:381–384.

- ↑ Klein, D.R. and L.S. Kolpashchikov, 1991. Current status of the Soviet Union’s largest caribou herd. In: C. Cutler and S.P. Mahoney (eds.). Proceedings of the 4th North American Caribou Workshop, pp. 251–255. St. John’s, Newfoundland.

- ↑ Post, E. and M.C. Forchhammer, 2002. Synchronization of animal population dynamics by large scale climate fluctuations. Nature, 420:168?171.

- ↑ Human Role in Reindeer/Caribou Systems project.