Antarctic Peninsula

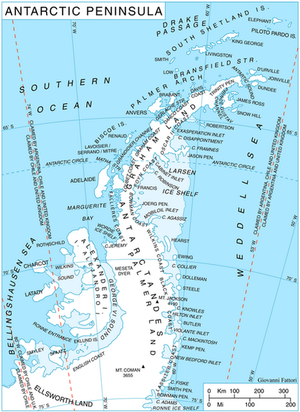

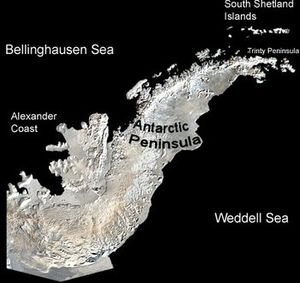

The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost element of mainland Antarctica, and the only part of the continent of Antarctica that extends outside the Antarctic Circle.

It is approximately 1200 miles (2000 km) long, stretching from 75°S (a drawn between Cape Adams (Weddell Sea) and a point on the mainland south of Eklund Islands) to 63°S (Prime Head on the Trinity Peninsula). The southern tip of South America, Cape Horn is about 610 miles (980 km) farther north, and is separated by the Drake Passage.

Other names applying to the region include: Tierra de O'Higgins (Chile), Tierra de San Martín (Argentina) and Península Antártica (other Spanish speaking countries). It has the mildest climate in Antarctica and contains the only two flowering plant species on the entire continent.

While Argentina, Chile and the United Kingdom have made territorial claims to the Antarctic Peninsula, it is governed under the Antarctic Treaty System which limits military activity and promotes scientific study (there are 28 research stations), environmental protection, and other peaceful activities.

Contents

Geography

The Antarctic Peninsula is essentially a mountain range, with peaks progressively higher as the range continues farther south. This range can be considered an extension of the Andes Mountain Range that runs virtually the length of South America.

The peninsula is heavily glaciated. The north eastern coast is dominated by Larsen Ice Shelf. Other permanent ice shelves cover much of the peninsula (George VI Ice Shelf, Wilkins Ice Shelf, Wordie Ice Shelf, Bach Ice Shelf. Rapid changes in ice cover and movement, including the breaking up of parts of the Larsen Ice Shelf have been attributed to global warming.

Volcanic activity occurs in various places including offshore in the South Shetland Islands.

Most of the landscape of the peninsula is considered Marielandia Antarctic tundra. Parts of the north western coast in particular become ice free for significant portions of the year and support vegetation (see below).

Separating the peninsula from nearby islands are numerous marine channels and straits, such as the Bransfield Strait that separates the mainland of peninsula from the South Shetland Islands.

West of the peninsula is the Bellingshausen Sea, north is the Drake Passage and Scotia Sea and east is the Weddell Sea. All of the waters surrounding the peninsula are part of the Southern Ocean.

Antarctic Treaty System

The Antarctic Treaty applies to the area south of 60° south latitude, including all islands and ice shelves. The whole area is subject to Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Flora and Fauna which are consolidated in the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. These include prohibitions on the killing, wounding, capturing or molesting of any native mammal or native bird except in accordance with a permit; and regulations on the importation of exotic species, parasites, and diseases. Permits may be issued only by persons authorized by a participating government. Additionally, numerous conservation areas are designated in several categories, and carry further regulation. For example, vehicles are prohibited to enter Specially Protected Areas.

The Antarctic Treaty has, for the time being, put a ban on any antarctic nuclear testing, radioactive waste disposal, and oil or other mineral drilling. It does not and cannot, however, prevent environmental degradation altogether. Much of the Antarctic ecosystem, particularly its flora, is extremely vulnerable to even the slightest natural or human disturbance.

Several thousand researchers and tourists visit the continent each year. The vast majority of tourism is concentrated at the more accessible and more hospitable Antarctic Peninsula, primarily being cruise ship tours. Overflight tours are also popular, and have a minimal impact on the local environment. Tourism in the Antarctic region dates back to 1891, when the first tourists were passengers on resupply ships to the sub-Antarctic islands. The first tour group visited the South Pole in 1988 by means of land-based flight operations. From 1983-93, a hotel, the Estrella Polar Guest House, operated on King George Island off of the west coast of the peninsula. Tourism is now, in fact, the primary non-governmental activity on the continent. While the majority of Antarctic tourists are highly educated and mindful of conservation issues, the continent’s fragile environment is vulnerable to very low levels of interference. Another issue is that private yachts also travel to Antarctica in increasing numbers since the 1980s. These activities were rarely recorded in the past, and are more difficult to regulate.

Climate

The west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula has a maritime Antarctic climate, similar to that of the South Sandwich, South Orkney, and South Shetland offshore islands. From the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula south to 68°S, average monthly temperatures exceed 0°C for three to four months of austral summer, and rarely fall below -10°C during austral winter. Precipitation averages 35 to 50 centimetres per annum with a considerable portion falling as rain during austral summer, occurring on two-thirds of the days of the year, with little seasonal variation in amounts. This can be compared to the higher rainfall of the sub-Antarctic islands (one to two metres per year), or the dry interior of the continent, which is virtual desert with only 10 cm precipitation per year.

Further south on the western coast of the peninsula as well as on the northeast coast to about 63°S, there is a drier maritime climate. Mean monthly temperatures exceeding 0°C for one to two months of summer, falling to -15°C in winter, and precipitation is 35 cm or less with occasional rain. Climate on the east coast of the peninsula south of 63°S is generally much colder due to the extensive pack ice of the Weddell Sea. Here, mean temperatures exceed 0°C for less than one month of summer and winter means are from –5 to –25°C. Precipitation ranges from ten to fifteen centimetrs. The peninsula is bisected by the Antarctic Circle, where approximately two hours of twilight occur during austral winter days, and there is close to 24 hours of sunlight during austral summer. [1].

Since the late 1940s, the average temperature of the Antarctic Peninsula has increased by 0.5°C per decade; a significant and rapid increase which is believed to be part of the global warming of the earth. In the past 20 years, seven ice shelves along the peninsula have retreated or disintegrated. Since 1995, three quarters of the Larsen Ice Shelf, located of the northeastern coast, has disappeared in a series of rapid calving disintegrations; most strikingly in 2002, when 1255 square miles (3260 square kilometers) of the Larsen Ice Shelf calved in a matter of weeks. In March 2008, the Wilkins Ice Sheet, located off the southwestern coast of the peninsula, lost more than 160 square miles (400 square kilometers) to a sudden massive calving event.[2]

Ecology

The Marielandia Antarctic tundra is defined as the coastal fringes of the Antarctic Peninsula, which are free of permanent ice.

The scattered ice-free areas of the Antarctic Peninsula and West Antarctica west of the Transantarctic Mountains are characterized by low temperatures, high aridity, and a short growing season. Cryptograms — mosses and lichens — dominate the vegetationof the Antarctic tundra. Vegetation of the Antarctic Peninsula’s botanic zone is similar to the field mark vegetation of the island highlands in the sub-Antarctic botanic zone. These closed cryptogamic communities occur in protected areas at lower elevations.

In all, approximately 300 species of algae, 200 lichens, 85 mosses, 25 liverworts, and only two flowering plant species are considered native to the [[Antarctic] continent].

Antarctica's two flowering plant species, the Antarctic Hair-grass (Deschampsia antarctica) and Antarctic Pearlwart (Colobanthus quitensis) are found on the northern and western elements of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Mammals and birds have a significant effect on vegetation despite the fact that none are herbivores. Elephant Seals flatten grass area and form wallow pools, and large bird rookeries are devoid of vegetation aside from algal sheets that occur on damp ground rich in bird excrement. Burrowing petrel species generally do not damage vegetation, but rather increase soil aeration and drainage.

Six seal species are native to Antarctica

- Crabeater Seal (Lobodon carcinophagus);

- Ross Seal (Omimatophoca rossii');

- Leopard Seal (Hydrurga leptonyx);

- Weddell Seal (Leptonychotes weddellii);

- Southern Elephant Seal (Mirounga leonina); and

- Antarctic Fur Seal (Arctocephalus gazella).

Elephant Seals are found in the Antarctic Peninsula area and on sub-Antarctic islands, but do not range as farther south into continental Antarctica. The elephant seal and fur seal are more often associated with the open ocean, while the others spend a significant amount of time on sea ice. Weddell Seal, Crabeater, Ross, and Leopard Seals are all ice-breeding marine mammals. Seals hauling out onto land can have a significant impact on vegetation communities. Pushed almost to extinction by intensive hunting in the 19th century, the Antarctic Fur Seal has recovered significantly starting around 1970, and now totals about one million individuals. The [[Crabeater] seal] is the most abundant seal on Earth, with a total population of over 30 million.

Thirty-seven flying seabird species are native to Antarctica. Some species characteristic of Marielandia are:

- Southern Fulmar (Fulmaras glacialoides);

- Southern Giant Fulmar (Macronectes giganteus);

- Cape Pigeon (Daption capense);

- Snow Petrel (Pagodroma nivea);

- Wilson’s Storm Petrel (Oceanites oceanicus);

- Blue-eyed Shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps);

- American Sheathbill (Chionis alba);

- South Polar Skua (Catharacta maccormicki);

- Brown Skua (Catharacta lonnbergi);

- Southern Black-backed Gull (Larus dominicanus); and,

- Antarctic Tern (Sterna vittata).

These birds must nest on ice-free areas, therefore, they are seldom found far inland over the ice cap, and breed during summer months when coastal areas are exposed. Several petrel species build burrows to nest in the ground.

Of the estimated total of 350 million birds of all species in the Antarctic, about 175 million are penguins. Six species of penguin are native to the Antarctic region:

- Adélie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae);

- Chinstrap Penguin (P. antarctica);

- Gentoo Penguin (P. papua);

- Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri);

- King Penguin (A. patagonicus);

- Rockhopper Penguin (Eudyptes crestatus); and,

- Macaroni Penguin (E. chrysolophus).

The Chinstrap and Gentoo Penguins breed primarily on the milder Antarctic Peninsula. Penguins likely could not thrive on the Antarctic Peninsula in such large populations, if carnivores such as Polar Bears, Arctic Foxes, or Arctic Wolves were present in Antarctica.

History

The first sighting of Graham Land occurred on January 30, 1820 by a British expedition headed by Edward Bransfield and piloted by William Smith sailing south from the South Shetland Islands when they observed "high mountains, covered with snow" and named the area Trinity Land. Eight months later a small boat of American seal hunters led by Nathaniel Palmer followed a similar route and sighted the same area, which was named Palmer Land.

For much of the nineteenth century a bitter debate was waged between British and American champions for each side claiming primacy in the discovery. This was reflected in competing names for the entire peninsula. Agreement on this name by the US-ACAN and UK-APC in 1964 resolved a long-standing difference over the use of the American name "Palmer Peninsula" or the British name "Graham Land" for this feature. (Graham Land is now that part of the Antarctic Peninsula northward of a line between Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz, whilst Palmer Land is the part southward of that line.

In 1952, the log of another American sealing ship, the Huron, came to light. It revealed that the ship's Master John Davis, looking for new seal sitings in the Huron's support vessel, the Ceciliam, sent a boat of men ashore on the north shore of the peninsula on February 7, 182. Finding no seals, the men returned after an hour to the Cecilia. Davis noted in the log, "I believe this Southern Land to be a Continent." Based upon his recorded position, Davis was in what is now named Hughes Bay, on the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. This appears to have been the first landing on the [[Antarctic] continent]. The next did not occur for another 74 years.

Because the Antarctic Peninsula is the most northerly part of the continent, reaching above the Antarctic Circle, it has the mildest climate and, on the north side at least, is the least icebound during the summer and therefore the most accessible. For these reasons, it received the most attention from early explorers. Among those who contributed to the revealing of the Antarctic Peninsula were:

- The Russian expedition of Thaddeus von Bellinghausen which discovered the Alexander Coast (now Alexander Island) (1820)

- British sealer/whaler John Biscoe who discovered Adelaide Island and for who the Biscoe Islands are named (1832)

- The US expedition of James Wilkes (1841)

- The Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897-1899)

- The Swedish Antarctic Expedition which over wintered on Snow Hill Island and Paulet Island (1901-4)

- The Third and Fourth French Antarctic Expeditions led by Jean-Baptiste Charcot which explored the west coast of the peninsula (1904-5 and 1908-10)

- Australian George Hubert Wilkins and Ben Eielson make first flight over the Peninsula (1928)

- The British Graham Land Expedition (1934-7)

- The U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition (1939-41)

- The British Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (1944-) established first permanent base

- The private US Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1947-8)

The International Geophysical Year (July 1957 to December 1958) dramatic expansion of exploration and scientific reasearch on the Antarctic Peninsula and the establishment of permanent research stations.

Research Stations

At least 28 nations maintain research stations in Antarctica. At least 14 have bases on the Antarctic Peninsula or near offshore islands, including:Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Ecudor, Peru, Poland, South Korea, Russia, Spain, United Kingdon, USA, Uraguay.

Research agenda vary, but that of the U.S. Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research Station on Anvers Island is indicative of the kind of scienctific activities underway in the region. Scientists at Palmer Stations study the Antarctic pelagic marine ecosystem, including sea ice habitats, regional oceanography and terrestrial nesting sites of seabird predators.

References

Further Reading

- National Science Foundation. 1991. Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) on the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP).

- EPA. 2001. Chapter 2: Affected Environment - the Physical and Biological Environment. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Rule on Environmental Impact Assessment of Nongovernmental Activities in Antarctica. Retrieved (2001) from: EPA.

- Draggan, S. 1993. Protection of Antarctic Microbial Habitats (pp. 603-614). In E. Imre Friedman (ed.). Antarctic Microbiology. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y. ISBN: 0471507768

- Fogg, G. E. 1998. The Biology of Polar Habitats. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y. ISBN: 0198549539

- Headland, R. K. 1996. Protected Areas in the Antarctic Treaty Region. Retrieved (2001) from: Scott Polar Research Institute.

- Purvis, W. 2000. Lichens. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D. C. ISBN: 1560988797

- Udvardy, M. D. F. 1975. A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world. IUCN Occasional Paper No. 18. International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Morges, Switzerland.

- Udvardy, M. D. F. 1987. The Biogeographical Realm Antarctica A Proposal. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 17:187-194.

- Watson, G. E., J. P. Angle, and P. C. Harper. 1975. Birds of the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic. American Geophysical Union, Washington, D. C. ISBN: 0875901247

- "Of Ice and Men" Account of a tourist visit to the Antarctic Peninsula by Roderick Eime

- Biodiversity at Ardley Island, South Shetland archipelago, Antarctic Peninsula

- 89 photos of the Antarctic Peninsula

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

Citation

Fund, W., & Hogan, C. (2013). Antarctic Peninsula. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Antarctic_Peninsula- ↑ Marielandia Antarctic tundra,World Wildlife Fund (Content Partner); Sidney Draggan, Topic Editor. 2007. "Marielandia Antarctic tundra." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). Published in the Encyclopedia of Earth November 10, 2006; Last revised February 4, 2007; Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ↑ European Space Agency, News release, November 28, 2008