Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study

This is Section 3.4.7 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; one of nine Arctic climate change case studies using indigenous knowledge. Case Study Authors: Sapmi:Tero Mustonen, Mika Nieminen, Hanna Eklund

This case study comes from a project carried out as part of the SnowChange program organized by the Environmental Engineering Department at Tampere Polytechnic in Finland[1]. SnowChange sponsored conferences in 2002 and 2003 at which arctic indigenous peoples, interested researchers, and other parties discussed their observations and concerns regarding their cultures and the effects of climate change and other aspects of the modern world. In addition, SnowChange researchers and students have conducted several projects around the Arctic, documenting indigenous observations and perspectives. The study took place in two locations: the small reindeer herding community of Purnumukka, in central Lapland, and the Saami communities of Nuorgam and Ochejohka (Utsjoki) in the northeast corner of Finland, the only part of the country where Saami represent the majority of the population. In Purnumukka, initial community contacts, networking, and interviews took place in September 2001. In March and April 2002, Mika Nieminen spent a month in the region, living and practicing reindeer herding with Pentti Nikodemus and Riitta Lehvonen and interviewing active herders, hunters, elders, and fishermen. SnowChange researchers have been in active communication with Purnumukka residents on a monthly basis since then. In Nuorgam and Ochejohka, SnowChange researchers spoke with elders, reindeer herders, fishermen, and cultural activists about the changes taking place in the local area and communities. The interviews were conducted in March 2002 in the Skallovaara reindeer corral area, in Ochejohka village, in Nuorgam, in the remote area of Lake Pulmanki, and in the village of Sirma, which is on the Norwegian side of the Deatnu (Teno or Tana) River.

Sapmi is the Saami homeland that extends across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Residents of the Finnish part of Sapmi have many concerns about changes that are taking place in their region. Not all changes are due to climate. The biggest environmental impacts in the region to date result from the construction for hydropower purposes of the Lokka reservoir in 1967 and the Porttipahta reservoir in 1970, and the massive clear cuts preceding the construction of the reservoirs. The best lichen areas were flooded and the herders had to move 5,000 reindeer from the grazing grounds because of the construction. These particular grazing grounds were excellent autumn grazing areas. Many people continue to refer to the creation of the reservoirs as a marker of great change, including changes in weather patterns, snowfall, and ice formation.

This case study presents comments by elders, as they carry the most extensive knowledge, with additions from the younger generation of Saami living in the region. Many more people were interviewed than are quoted here. The quotes used are considered to best illustrate the themes and ideas that typify what was learned from the Saami interviewed and provides insight into what the changes mean for people in the area. The interviews covered more material than is presented in this brief case study. Some of the additional material was reported in the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA) Report, Section 3.3 (Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study).

The following people are quoted in this case study.

- Veikko Magga – a reindeer herder for over 50 years and a member of the reindeer herders association of Lapin Paliskunta

- Niila Nikodemus – an 86-year-old elder and the oldest reindeer herder in Purnumukka

- Heikki Hirvasvuopio – 65 years old and still active in reindeer herding

- Aslak Antti Länsman – 55 years old and a local reindeer herder belonging to the Polmak Lake Siida

- Niillas Vuolab – an elder and the oldest reindeer herder in Ochejohka. Niillas Vuolab was born in the Saami Community of Angel in 1916 and came to Ochejohka in the autumn of 1916

- Ilmari Vuolab – the son of Niillas Vuolab. Ilmari Vuolab was a 51-year-old reindeer herder from the reindeer herding area of Kaldoaivi. He passed away in April 2003

- Taisto Länsman – a reindeer herder from Lake Pulmanki with extensive written records of the ice break-ups in the lake

Contents

Weather, rain, and extreme events (3.4.7.1)

Heikki Hirvasvuopio reflected on the seasonal changes and the autumn weather.

Temperatures used to be well below freezing in autumn and winter came when it was supposed to. It was not mild autumn like now. It used to be longer, snow would fall. Now sleet and rain will fall. Summers used to be to the "standard form", this means that fair weather would stay longer. We would have the reindeers in the big fell areas because especially the beginning of the summer would be very hot. Insects would be there as well with the reindeers. Now this has changed. The summers are very unstable. Reindeer are staying in the forests now; they do not go up to the fells any more.

Veikko Magga reported that the amount and consistency of snowfall has fluctuated in Purnumukka and the Vuotso region.

It is springtime nowadays when the snow actually comes. Some comes in the autumn, but there is no proper freezing, only so that the lower-most snow freezes. The lichen freezes solid into this layer and the reindeer cannot get proper food because of this. For a couple of years in a row there has been less snow in the autumn than previously but I think sometimes it falls earlier, sometimes later. It has always been this way.

Niila Nikodemus discussed snow and ice cover based on his extensive experience and a lifetime of observations.

There is normal fluctuation in the amounts of snow. However, snow falls later. In the 1950s and 1960s, there used to be a permanent snow cover always in October. Starting in the 1970s, it can be November, middle of November. Ice has thinned, especially in the small rivers and ditches here. I wonder if the reservoirs affected this? It used to be that we could just drive away on the ice. There used to be a proper ice cover on the small rivers.

Heikki Hirvasvuopio outlined the impacts of climate change on the reindeer herding.

During autumn times, the weather fluctuates so much, there is rain and mild weather. This ruins the lichen access for the reindeer. In some years this has caused massive loss of reindeers. It is very simple – when the bottom layer freezes, reindeer cannot access the lichen. This is extremely different from the previous years. This is one of the reasons why there is less lichen. The reindeer has to claw to force the lichen out and the whole plant comes complete with roots. It takes, as you know, extremely long for a lichen to regenerate when you remove the roots of the lichen. This current debate of loss of grazing grounds is not therefore connected with a larger number of reindeers, this is not the case. In previous years, the numbers of the herds were much bigger. The main reason for the loss of grazing lichen areas is the bad weather conditions that contribute to the bigger impact on the area. I do not think many people have observed this reason in their thinking.

Aslak Antti Länsman said that for the past ten years the autumns have been mild with sleet, which has frozen the surface of the ground.

This has affected the reindeer economy for sure. As the ice cover was there this had a negative impact on the reindeer herding. It is a big question mark why these changes are taking place. Is it so called greenhouse effect, or air pollution? Or is it connected with the same events that melted the last ice age? Who knows?

Ilmari Vuolab stated:

Yes, the weather conditions have changed overall so it is not possible to be certain that this amount of snow will be at this time. This is a problem.

Birds (3.4.7.2)

Heikki Hirvasvuopio talked about the disappearance of birds in Kakslauttanen.

…especially with ground birds, we could be talking about a near extermination when compared to the previous amounts. I used to hunt them quite a lot while reindeer herding, so I have a good idea of the stocks. We cannot even talk now about the same amounts during the same day. This affects especially ptarmigans, capercaillie, and ground birds. With small singing birds, the same trend is visible. Nowadays it is silent in the forest – they do not sing in the same way anymore. It used to be that your ears would get blocked as the singing was so powerful before. They have disappeared completely as well.

Taisto Länsman was concerned that there were far fewer small birds compared to his childhood. Niillas Vuolab shared the concern and stated that:

Nature has grown much poorer. For example during summers migratory birds are fewer today. We see the usual species, but the numbers are down. Especially marine birds, such as long-tailed ducks Hyemalis, white-winged scoters Fusca, black scoters Nigra; we do not see these anymore. After the war and even later great big flocks would come here. I feel ptarmigans have diminished as well.

Insects (3.4.7.3)

Heikki Hirvasvuopio said:

Both mosquitoes and gadflies have disappeared. Especially we can see gadflies disappearing. And the reason is that in the olden times reindeers had to move up to the big fells as the vermin were plentiful then.

Niila Nikodemus pointed out that:

The Of insects really depends on the particular summer. If it is a rainy springtime they will be plenty, but if it will be a dry spring, hardly any will appear.

Traditional calendar and knowledge (3.4.7.4)

Veikko Magga stated:

Traditional knowledge has changed like reindeer herding in a negative direction. We have to feed the reindeers with hay and fodder quite much now. But I would not advocate that the traditional Saami calendar is mixed up yet. But traditional weather reading skills cannot be trusted anymore. In the olden times one could see beforehand what kind of weather it will be. These signs and skills holds true no more. Old markers do not hold true, the world has changed too much now. We can say nature is mixed up now. An additional factor is that reindeer herding is being pressured from different political, social, and economic fronts at all times now. Difficulties are real. A way of living that used to support everything is now changing and people do not find employment enough.

Heikki Hirvasvuopio discussed traditional forecasts.

The periods of weather are no longer the norm. We had certain stable decisive periods of the year that formed the traditional norms. These are no longer at their places. Certain calendar days, like Kustaa Vilkuna Finnish folk historin of wether nd culture from the midtwentieth century wrote, held really true. But these are no longer so. Today we can have almost 30 degrees of variation in temperature in a very small time period. In the olden days the Saami would have considered this almost like an apocalypse if similar drastic changes had taken place so rapidly. Before I spent all of my winters in the forest and was at home for one week at the most. Nowadays the traditional weather forecasting cannot be done anymore as I could before. Too many significant and big changes have taken place. Certainly some predictions can be read from the way a reindeer behaves and this is still a way to look ahead, weather-wise. But for the markers in the sky we look now in vain. Long term predictions cannot be done anymore.

Ilmari Vuolab stated that:

The traditional markers of the nature do not hold true anymore. Ecosystem seems to have changed. It is a very good question, as what has contributed to the change. It cannot be all because of cyclic weather patterns of different years. I believe the changes we have seen are a long-term phenomenon. The wise people say that changes will be for the next 100 years even if we act now to reduce emissions. It is obvious that the reindeer herding is the basis of the Saami culture here and other subsistence activities that are related to the nature, such as picking cloudberries or ptarmigan hunting. I feel the Saami have been always quite adaptive people and we adapt to the changes as well. After all, climate changes in small steps, not in one year.

3.1. Introduction (Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study)

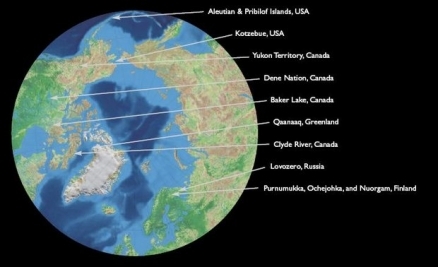

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam climate change case study. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Sapmi:_the_communities_of_Purnumukka,_Ochejohka,_and_Nuorgam_climate_change_case_study- ↑ Mustonen, T. and E. Helander (eds.), 2004. Snowscapes, Dreamscapes: SnowChange book on community voices of change. Tampere Polytechnic Institute, Finland, 562p.