Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations climate change case study

This is Section 3.4.3 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; one of nine Arctic climate change case studies using indigenous knowledge.

Case Study Author: The Yukon Territory: Cindy Dickson

The Council of Yukon First Nations held a series of workshops in February 2003 to address climate change. On February 12 and 13, twenty elders representing the Elders Council of the Council of Yukon First Nations took part in the Elders Climate Change Workshop. This workshop happened as a result of suggestions given by community elders. They said that the changing northern climate was an important issue because it had implications for human health and cultural survival. Following a round-table discussion, the elders divided themselves into three groups – representing the north, central, and south Yukon regions. Each elder shared his or her knowledge and concerns about changes in weather and how these changes have affected the way of life in their nation’s traditional territory. A second Yukon First Nations Climate Change Forum was held February 26 and 27, 2003. Elders, community representatives, scientists, and government representatives participated in the forum. Elders listened to explanations of government programs and research and provided suggestions as to how federal and territorial governments and researchers could work in partnership with Yukon First Nations communities to develop a longterm strategy for climate change.

Yukon First Nations elders share a growing concern about the changes that are taking place on their lands and in their way of life. Climate change is responsible for some but not all of these changes. Contaminants from local sources and long-range transport have been a source of worry for cultural activities such as trapping, hunting, and eating traditional foods, resulting in changes to community social life. As the environment has changed, people have had to learn to cope with the change. Understanding why things have changed and why this is happening helps people adjust. Yukon elders want to share what they know, and to learn as much as they can from others about climate change and its impacts. Only through knowledge and the ability to take action for themselves will Yukon First Nations be able to respond effectively to climate change.

At the Elders Climate Change Workshop and the Yukon First Nations Climate Change Forum, elders and community representatives described the changes that they have seen. For example, in the northern Yukon, freezing rains in November have meant that animals cannot eat. Birds that usually migrate south in August and September are now being seen in October and November. In some areas, thawing permafrost has caused the ground to drop and in some cases has made the area smell foul. In more southerly communities, rings around the moon are no longer seen, although they are still visible in the northernmost community. There are increased sightings of new types of insect and an increase in cougar (Puma concolor) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). People used to be able to predict when it would get colder by looking at tree leaves. It is difficult to do that now. Lakes and streams are drying up, or are becoming choked with weeds, making the water undrinkable. Many animals are changing their distribution and behavior. Polar bears used to go into their dens in October and November, but are now out until December. One bear was spotted in winter sleeping under a tree but above ground, rather than in a den, which was regarded as an exceptional and unprecedented sighting.

Many of these changes have been observed since the 1940s, although some began earlier. These changes have produced much concern and anxiety. People are concerned about the future. Habits have changed, so that people now depend more and more on market foods and eat fewer traditional foods. In the face of such changes, people often mobilize to take action. One result in the Yukon is that elders are willing to assist in developing a strategy and are prepared to find ways to cope with the changes, as difficult as that may be. In many statements, the elders expressed their fears about these changes. One said that he had never expected to see the day when people would worry about water, but now he hears about that all the time. Another remembered, "We were able to read the weather, what it was going to be like".

At the workshops, Yukon First Nations elders made it clear that partnerships must be developed between the federal government, the territorial government, and Yukon First Nations, as well as with scientists and non-governmental organizations. Each community must have the ability to prepare for change and to be a part of designing the strategies that are being developed in relation to climate change. At the international level, Yukon First Nations elders have shared their traditional knowledge and cultural values to help shape policies through the Arctic Athabaskan Council. The elders and community representatives concluded that their workshops were just a start. More is needed. To that end, an elders panel of five members has been created. This is to be consulted and to have a representative who will work with the Council of Yukon First Nations and the Arctic Athabaskan Council.

3.1. Introduction (Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations climate change case study)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations climate change case study)

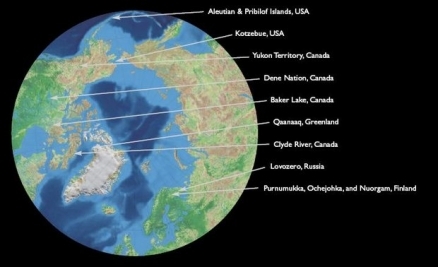

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations climate change case study)