Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic

This is Section 3.5 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Authors: Henry Huntington, Shari Fox; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Igor Krupnik; Case Study Authors are identified on specific case studies; Consulting Authors: Anne Henshaw,Terry Fenge, Scot Nickels, Simon Wilson

The Arctic is by nature highly variable. The availability of many resources is cyclical or unpredictable. For example, there are always uncertainties in caribou migrations. The lesser snow geese may arrive early or late; the nesting success varies considerably from year to year. Weather is changeable and inconsistent. There are large natural variations in the extent of sea-ice cover from year to year, and in freeze-up and break-up dates. Erosion, uplift, thermokarst, and plant succession change landscapes and coastlines. The peoples of the Arctic are familiar with these characteristics of their homeland, and recognize that surprises are inherent in their ecosystems and ways of life. That is why indigenous peoples tend to be flexible in their ways and to have cultural adaptations, such as mobile hunting groups and strong sharing ethics, that help deal with environmental variability and uncertainty[1]. Many of the points raised in this section are discussed further in Chapter 17 (Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic).

Against this backdrop, especially in a time of rapid social change, climate change may be regarded as simply another aspect of the variable and challenging Arctic (see Box 3.4). Just as easily, it can be dismissed from further thought as a vast, slow, and unstoppable force to be accommodated over time, in contrast to rapid, worrisome, and potentially tractable political, economic, and social problems. Some of these larger socio-economic changes have had significant impacts on lifestyles and culture, including the erosion of indigenous knowledge and the social standing of its holders[2]. While some observers hold that impacts of climate change will be devastating for indigenous peoples over the course of the next several decades, others argue that climate change in the shorter term will be less important than existing and ongoing economic, cultural, and social changes. It is important, however, to be cautious in making comparisons between impacts from the very different phenomena of climate change and social change.

The case studies in this chapter show that while both views have some legitimacy, by themselves they are simplistic and inaccurate portrayals of how climate change is perceived by arctic residents. The chapter title itself is plural, reflecting the diversity of ways in which climate change and the arctic environment are seen by indigenous peoples of the Arctic. Even within one group, there is a range of views, and differences in the perceived importance of various threats, of which climate change is only one[3]. A comprehensive survey of the many and varied perspectives of all arctic residents has not been possible, and it is not clear in any case how valuable such a survey would be. The case studies herein illustrate that while generalizations are possible, the particular circumstances, location, economic base, and culture of a particular group, as well as each individual’s personal history and experiences, are crucial factors in determining how and what people think about climate change, how climate change may or may not affect them, and what can or cannot be done in response.

|

Box 3.4. Political relations, self-determination, and adaptability Social pathologies resulting from social change clearly weigh more heavily on the minds of northerners now than the effects of climate change. It is important, however, to be careful when comparing social change apples with climate change oranges.The ACIA climate change scenarios point to very significant environmental changes across most of the Arctic within a couple of generations. Notwithstanding high levels of suicide and other social pathologies in many northern communities, many indigenous peoples in the Arctic are interacting with, and adapting to, changing economic and social circumstances and the adoption of new technologies, in short, to “globalization”. In the midst of globalization, arctic indigenous peoples still identify themselves as arctic indigenous peoples. But the sheer magnitude of projected impacts resulting from climate change raises questions of whether many of the links between arctic indigenous peoples and the land and all it provides will be eroded or even severed. Certainly arctic indigenous peoples are highly skilled in and accustomed to adapting, as the archaeological and historical records and current practices illustrate. Adapting to climate change in the modern age, however, may be a very different prospect than adaptations in the past. It is clear that support from regional and national governments will be important for the effectiveness of the adaptations required. Herein lies a crucial point: the policies and programs of regional and national governments can encourage, enable, and equip northerners to adapt to climate change, although it is important to note that the projected magnitude of change in the Arctic may, eventually, overwhelm adaptive capacity no matter what policies and programs are in place. On the other hand, policies and programs of national governments could, conceivably, make adaptation more strained and difficult by imposing further constraints at levels from the individual to the regional. Empowering northern residents, particularly indigenous peoples, through self-government and self-determination arrangements, including ownership and management of land and natural resources, is a key ingredient that would enable them to adapt to climate change. Indigenous peoples want to see policies that will help them protect their self-reliance, rather than become ever more dependent on the state.There are compelling reasons for the national governments of the arctic states to provide northerners, specifically indigenous peoples, with the powers, resources, information, and responsibilities that they need to adapt to climate change, and to do so on their own terms. Berkes and Jolly (2001) provide a practical and positive example of what needs to be done.The ability of Inuvialuit of the Canadian Beaufort Sea region to adapt to climate change is grounded in the Inuvialuit Final Agreement, which recognizes rights of land ownership, co-operative management, protected areas, cash, and economic development opportunities. For indigenous peoples themselves, their own institutions and representative organizations must learn quickly from the well-documented adaptive efforts of hunters as well as from positive examples such as the Inuvialuit Final Agreement. National governments, often slow moving and ill equipped to think and act in the long term, must also understand the connections between empowerment and adaptability in the north if their policies and programs are to succeed in helping people respond to the long-term challenge posed by climate change. |

The archeological record reveals that, with or without modern anthropogenic influences, the arctic climate has experienced sudden shifts that have had severe consequences for the people who live there[4]. In some cases, people have simply died as resources dwindled or became inaccessible. In other cases, communities moved location, or shifted their hunting and gathering patterns to adapt to environmental change. Indigenous peoples today have more options than in the past, but not all of these allow for the retention of all aspects of their cultures or for maintaining their ways of life. For example, many of these options have become available at the cost of dependency on the outside world. A wider range of foods is available, but communities are less self-sufficient than before. Settled village life provides educational opportunities, but indigenous knowledge is eroded because its transmission requires living on the land[5]. Considerable infrastructure has been built over the past century, bringing improvements in the material standard of living in the Arctic. At the same time, the settled way of life has reduced both the flexibility of indigenous peoples to move with the seasons to obtain their livelihoods and the extent of their day-to-day contact with their environment, and thus the depth of their knowledge of precise environmental conditions. Instead, they have become dependent on mechanized transportation and fossil fuels to carry out their seasonal rounds while based in one central location. Together, these dependencies have increased the vulnerability of arctic communities to the impacts of climate change.

Resilience is the counterpart to vulnerability. It is a systems property; in this case, a property of the linked system of humans and nature, or socio-ecological systems, in the Arctic. Resilience is related to the magnitude of shock that a system can absorb, its self-organization capability, and its capacity for learning and adaptation[6]. Resilience is especially important to assess in cases of uncertainty, such as anticipating the impacts of climate change. Managing for resilience enhances the likelihood of sustaining linked systems of humans and nature in a changing environment in which the future is unpredictable. More resilient socio-ecological systems are able to absorb larger shocks without collapse. Building resilience means nurturing options and diversity, and increasing the capability of the system to cope with uncertainty and surprise[7]. Examining climate change and indigenous peoples in this way can illuminate some of the reasons that indigenous perspectives are a critical element in responding to climate change.

Life in the Arctic requires great flexibility and resilience in this technical sense. Many of the well known cultural adaptations in the Arctic, such as small group and individual flexibility and the accumulation of specialist and generalist knowledge for hunting and fishing, may be interpreted as mechanisms providing resilience[8]. Such adaptations enhance options and were (and still are) important for survival. If the caribou or snow geese do not show up at a particular time and place, the hunter has back-up options and knows where to go for fish or ringed seals instead. However, cultural change and loss of some knowledge and sensitivity to environmental cues, and developments such as fixed village locations with elaborate infrastructure that restrict options, may reduce the adaptive capacity of indigenous peoples.

One approach to improve the situation is to develop policy measures that can help build resilience and add options. For example, Folke et al.[9] have suggested that one such policy direction may be the creation of flexible multi-level governance systems that can learn from experience and generate knowledge to cope with change. In this context, the significance of indigenous observations includes their relevance for understanding the processes by which people and communities adapt to climate change.

While the scale of the impacts of climate change over the long-term is projected to be very significant, it is not yet clear how quickly these changes will take place or their spatial variation within the circumpolar Arctic. Be that as it may, human societies will attempt to adapt, constrained by the cultural, geographic, climatic, ecological, economic, political, social, national, regional, and local circumstances that shape them. As with all adaptations, those that are developed in the Arctic in response to climate change will protect some aspects of society at the expense of others. The overall success of the adaptations, however, will be determined by arctic residents, probably based in large part on the degree to which they are conceived, designed, developed, and carried out by those who are doing the adapting.

Nevertheless, support from regional and national governments may be important for the effectiveness of the adaptations required. For example, Berkes and Jolly[10] have argued that co-management institutions in the Canadian Western Arctic under the Inuvialuit Final Agreement have been instrumental in relaying local concerns across multiple levels of political organization. They have also been important in speeding up two-way information exchange between indigenous knowledge holders and scientists, thus enhancing local adaptation capabilities by tightening the feedback loop between change and response[11].

In this regard, response by the community itself, through its own institutions, is crucial to effective adaptation. Directives from administrative centers or solutions devised by outsiders are unlikely to lead to the specific adaptations necessary for each community. Indigenous perspectives are needed to provide the details that arctic-wide models cannot provide. Indigenous knowledge perspectives can help identify local needs, concerns, and actions. This is an iterative rather than a one-step solution because there is much uncertainty about what is to come. Thus, policies and actions must be based on incomplete information, to be modified iteratively as the understanding of climate change and its impacts evolve.

Indigenous perspectives are also important in that indigenous peoples are experts in learning-by-doing. Science can learn from arctic indigenous knowledge in dealing with climate change impacts, and build on the adaptive management approach – which, after all, is a scientific version of learning-by-doing[12]. Multi-scale learning is key – learning at the level of community institutions such as hunter-trapper committees, regional organizations, national organizations, and international organizations such as the Arctic Council. The use of adaptive management is a shift from the conventional scientific approach, and the creation of multi-level governance, or co-management systems, is a shift from the usual top-down approach to management.

One significant aspect of the indigenous perspectives introduced in this chapter is that they help illustrate that the vulnerability and resilience of each group or community differ greatly from place to place and from time to time. In considering the impacts of climate change in the Arctic and the options for responding to those changes, it is essential to understand the nature of the question. It is also essential to consider what is at stake. The indigenous peoples of the Arctic are struggling to maintain their identity and distinctive cultures in the face of national assimilation and homogenization, as well as globalization[13]. The response to climate change can exacerbate or mitigate the impacts of that climate change itself. For policymakers, taking the nature and diversity of indigenous perspectives into account is essential in the effort to help those groups adapt to a changing climate.

For indigenous peoples themselves, an understanding of the ways in which they are resilient and the ways in which they are vulnerable is an essential starting point in determining how they will respond to the challenges posed by climate change. As noted, physical, ecological, and social forces interact to shape these characteristics for each group of people. In times of rapid change, the dynamics of this interplay are particularly difficult for a society to track. An assessment of individual and collective perspectives of arctic indigenous peoples on the challenges ahead can help determine strengths, weaknesses, and priorities. This chapter is a first step in the direction of such an assessment, and shows the need for further work to enable indigenous communities in the Arctic to reflect on the implications of climate change for themselves and for their future.

3.1. Introduction (Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic)

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

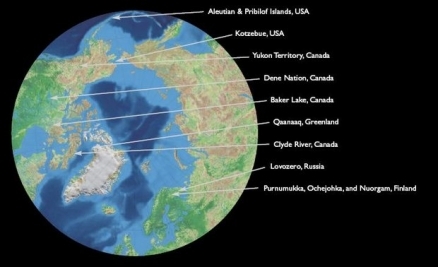

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Indigenous perspectives and resilience of the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Indigenous_perspectives_and_resilience_of_the_Arctic- ↑ Berkes, F. and D. Jolly, 2001. Adapting to climate change: socialecological resilience in a Canadian Western Arctic community. Conservation Ecology, 5(2):18 www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art18.–Krupnik, I., 1993. Arctic Adaptations: Native Whalers and Reindeer Herders of Northern Eurasia. University Press of New England, xvii + 355p.–Smith, E. A., 1991. Inujjuamiut Foraging Strategies: Evolutionary Ecology of an Arctic Hunting Economy. Aldine de Gruyter, xx + 455p.

- ↑ Dorais, L.-J., 1997. Quaqtaq: Modernity and Identity in an Inuit Community. University of Toronto Press, ix + 132p.

- ↑ Fox, S., 2002. These are things that are really happening: Inuit perspectives on the evidence and impacts of climate change in Nunavut. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 12–53. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ McGhee, R., 1996. Ancient People of the Arctic. University of British Columbia Press, xii + 244p.

- ↑ Ohmagari, K. and F. Berkes, 1997. Transmission of indigenous knowledge and bush skills among the Western James Bay Cree women of subarctic Canada. Human Ecology, 25:197–222.

- ↑ Folke, C., S. Carpenter, T. Elmqvist, L. Gunderson, C.S. Holling, B. Walker, J. Bengtsson, F. Berkes, J. Colding, K. Danell, M. Falkenmark, L. Gordon, R. Kasperson, N. Kautsky, A. Kinzig, S. Levin, K.-G. Maler, F. Moberg, L. Ohlsson, P. Olsson, E. Ostrom, W. Reid, J. Rockstrom, H. Savenije and U. Svedin, 2002. Resilience for Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. Environmental Advisory Council, Ministry of the Environment, Stockholm, 74p.–Resilience Alliance, 2003. The Resilience Alliance. www.resalliance.org

- ↑ Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke (eds.), 2003. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge University Press.–Folke, C., S. Carpenter, T. Elmqvist, L. Gunderson, C.S. Holling, B. Walker, J. Bengtsson, F. Berkes, J. Colding, K. Danell, M. Falkenmark, L. Gordon, R. Kasperson, N. Kautsky, A. Kinzig, S. Levin, K.-G. Maler, F. Moberg, L. Ohlsson, P. Olsson, E. Ostrom, W. Reid, J. Rockstrom, H. Savenije and U. Svedin, 2002. Resilience for Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. Environmental Advisory Council, Ministry of the Environment, Stockholm, 74p.

- ↑ Berkes, F. and D. Jolly, 2001. Adapting to climate change: socialecological resilience in a Canadian Western Arctic community. Conservation Ecology, 5(2):18 www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art18.–Fox, S., 2002. These are things that are really happening: Inuit perspectives on the evidence and impacts of climate change in Nunavut. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 12–53. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Folke, C., S. Carpenter, T. Elmqvist, L. Gunderson, C.S. Holling, B. Walker, J. Bengtsson, F. Berkes, J. Colding, K. Danell, M. Falkenmark, L. Gordon, R. Kasperson, N. Kautsky, A. Kinzig, S. Levin, K.-G. Maler, F. Moberg, L. Ohlsson, P. Olsson, E. Ostrom, W. Reid, J. Rockstrom, H. Savenije and U. Svedin, 2002. Resilience for Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. Environmental Advisory Council, Ministry of the Environment, Stockholm, 74p.

- ↑ Berkes, F. and D. Jolly, 2001. Adapting to climate change: socialecological resilience in a Canadian Western Arctic community. Conservation Ecology, 5(2):18 www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art18.

- ↑ Smith, D., 2001. Co-management in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. In: Arctic Flora and Fauna: Status and Trends, pp. 64–65. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Helsinki.

- ↑ Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke (eds.), 2003. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R. (ed.), 2000. Endangered Peoples of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive. The Greenwood Press, xix + 278p.–Nuttall, M., 1998. Protecting the Arctic: Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival. Harwood Academic Publishing, 204p.