Qaanaaq climate change case study

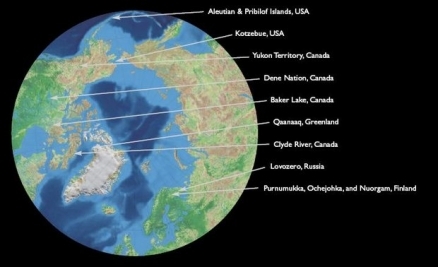

This is Section 3.4.6 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; one of nine Arctic climate change case studies using indigenous knowledge.

Case Study Authors: Qaanaaq, Greenland: Uusaqqak Qujaukitsoq, Nuka Møller

Uusaqqak Qujaukitsoq is a hunter from Qaanaaq, North Greenland. He has served in the Greenland Parliament and on the Executive Committee of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference. Uusaqqak has been involved in many natural resource use and conservation issues, including the Greenland Home Rule Government’s seal skin campaign. His comments were made in response to an invitation to describe climate changes that have occurred in his region.

Change has been so dramatic that during the coldest month of the year, the month of December 2001, torrential rains have fallen in the Thule region so much that there appeared a thick layer of solid ice on top of the sea ice and the surface of the land. The impact on the sea ice can be described in this manner: the snow that normally covers the sea ice became nilak (freshwater ice), and the lower layer became pukak (crystallized ice), which was very bad for the paws of our sled dogs.

In January 2002, our outermost hunting grounds were not covered by sea ice because of shifting wind conditions and sea currents. We used to go hunting to these areas in October only four or five years ago. It is hard to tell what impact such conditions will have to the land animals. Since I haven’t been out to see the feeding grounds of the arctic hares (Lepus arcticus), musk ox (Ovibos moschatus), and reindeer this year, I can’t tell how it is, but I can guess that it will be difficult for the animals to find anything to feed on because of the layer of ice that covers everything. It is hard to say what can be done about these conditions.

Sea-ice conditions have changed over the last five to six years. The ice is generally thinner and is slower to form off the smaller forelands. The appearance of aakkarneq (ice thinned by sea currents) happens earlier in the year than normal. Also, sea ice, which previously broke up gradually from the floe-edge towards land, now breaks off all at once. Glaciers are very notably receding and the place names are no longer consistent with the appearance of the land. For example, Sermiarsussuaq ("the smaller large glacier"), which previously stretched out to the sea, no longer exists.

3.1. Introduction (Qaanaaq climate change case study)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Qaanaaq climate change case study)

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Qaanaaq climate change case study)