One Lifeboat: Chapter 2

Contents

China's Growth and Consequences

The rapid growth of the Chinese economy since the 1970s, but particularly in the past 10 years, has caused reverberations in global markets. This tendency has been further reinforced following China’s WTO accession. The quest for resources to support China’s growth; increasing emissions; surging commodity prices; China’s overseas investments; and rapidly increasing exports of manufactured goods have become topics regularly covered by the world’s media, and tracked by many organizations. With this newfound prosperity, many more Chinese are travelling abroad, bolstering tourism and schools in many countries. Investment by China’s government and enterprises in other countries is accelerating, and is being given intense scrutiny internationally.

Comparative Situation

China’s contribution to the growth of the global GDP since 2000 has been almost double that of Brazil, India and Russia combined—the three largest emerging economies after China. Since 1990, China’s economy has grown over nine per cent on average annually and it is likely that this growth will continue to grow by eight per cent or more a year. At this rate, by 2015, China will be the third largest economy of the world with about 6.5 per cent of world GDP, using a 2000 real dollar exchange rate. By comparison, Japan during its phase of rapid growth, between 1971 and 1991, on average grew only by 3.85 per cent annually.

According to The Economist,[1] China manufactures 30 per cent of all of the world’s television sets; 50 per cent of the world’s cameras; and 70 per cent of the world’s photocopiers. It also accounts for 30 per cent of the world’s furniture trade. China also has become a major player in world markets for oil, metals and raw materials, and commodities such as grain soybeans, fruits, vegetables and seafood.[2] No doubt the sudden increase of production capacity initially came as a result of Deng Xiaoping’s call for rapid growth in 1992. What makes its current level so remarkable is its sustained nature, even as other nations in Asia faced serious downturns in the late 1990s. Various authors have been pondering over the reasons for China’s rapid and sustained growth. The reasons most often cited include: high productivity due to important structural changes; foreign, as well as domestic investment; and the opening of the Chinese economy to international trade.

China continues to be a leading exporter of manufactured goods including electronics, clothing and furniture, and the world’s largest consumer and importer of many raw materials. Its total trade in goods grew at an annual rate of 24.5 per cent during the 10th Five-Year Plan period (2000–2005), and the target set for the 11th Five- Year Plan period (2006–2010) is to increase its trade in goods from US$142.2 billion in 2005 to US$230 billion in 2010.[3]

When China was the 25th largest exporter in the world, a decade ago, this routine doubling was hardly noticeable in the world. Now that it is either number three or four, it is truly astounding. And the environmental implications will be considerable in the years ahead, for environmental effects tend to unveil themselves more gradually than the economic successes with which they are associated.

In the next 15 years, China will build its fundamental transportation, urban, water control, energy and other infrastructure that will serve the nation for decades to come. Half the concrete and steel used in the world is in China. And up to 2015, half of the world’s new buildings will be constructed in China. These demands cause Chinese suppliers to scour their own country and the world for the raw materials and manufactured products to meet these immense, very immediate needs. They also stimulate a rapid industrial development response within China that sometimes creates overbuilding and surplus, for example in the steel industry. Chinese manufacturers then become exporters. The U.S. steel industry, feeling the pressure of Chinese steel exporters, calls this “The China Syndrome.” A further consequence of this rapid development is the creation of some infrastructure that simply meets a relatively low standard of energy efficiency, and with limited potential for contributing to environmental protection. Some, but not all, Chinese building construction falls in this category, and so do many of China’s coal-fired power plants.

Information on China’s environmental performance during the past years of rapid growth, compared to selected nation groups, has been compiled in a separate report for CCICED prepared by Dr. Stephen Lonergan.[4] His report draws upon best available international sources, but these sources provide only a very approximate picture. In some instances, the results reveal that China has made dramatic progress over a 10-to-20-year time period, for example, on energy efficiency. And overall per capita production of pollutants, and use of resources are relatively low. Yet in aggregate, China has moved into the major leagues. For example, the rise in carbon dioxide emissions is dramatically increasing so that China is now behind only the U.S, and will soon become number one in the world. These dynamics have caught everyone by surprise, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) repeatedly having to update its forecasts of China’s situation.[5]

Ecological Footprint

Ecological footprint calculations allow comparing and tracking of natural resource consumption and efficiency at the per capita level. The advantage is that the actual net consumption per person of resources, taking imports and exports into account, can be compared, irrespective of the size of a country. As an example, China’s ecological footprint in 2001 amounted to 1.5 global hectares (ha)/person, considerably below the world average (2.2 global ha/person); lower than other Asian countries such as Japan (4.3 global ha/person) and Malaysia (3.0 global ha/person); and well below the U.S. (9.5 global ha/person) and Western Europe (5.1 global ha/person). But China’s ecological footprint in 2001 was higher than some other Asian countries, e.g., India (0.8 global ha/person) or Indonesia (1.2 global ha/person), and has likely been growing in the past five years.

China’s “Export of Biocapacity”

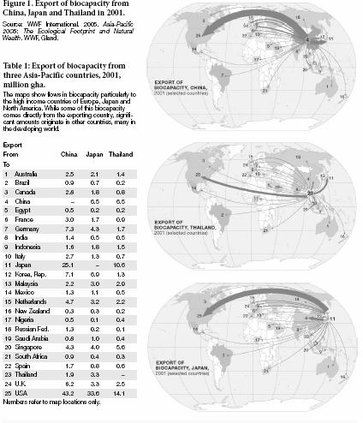

The 2005 Asia-Pacific report on ecological footprints[6] compares the export of biocapacity (biological capacity)[7] from Asian countries (see Figure 1), which provides a clear notion of the fact that, contrary to common perceptions in the West, China as yet is not a high-consuming country for natural resources per se, but an increasingly important manufacturer of goods consumed elsewhere in the world.

Import of Natural Resource Commodities

Nevertheless, China’s rapid economic growth, industrialization and urbanization face major resource constraints. Its large population will make domestic resource constraints even more significant in the future. China is now the largest consumer and producer in the world of many different commodities. It is the second largest consumer of primary energy after the U.S., and the top global producer of coal, steel, cement and 10 different kinds of non-ferrous metals. Its increasing appetite for commodities is driving global demand for everything from oil and steel to copper and aluminum. In recent years, due to its robust growth, China has replaced the United States as the dominant market and price setter for copper, iron ore, aluminum, platinum, etc.

China’s total forest imports in volume went up from 40 million cubic meters (m3) in 1997 to 134 million m3 in 2005. China’s agricultural imports also are expanding. It increased imports of cotton from the United States by 700 per cent. China’s grain production has declined in the past few years. According to World Bank’s forecasting, China’s net grain imports will rise to 19 million tonnes in 2010 and 32 million tonnes in 2020.

The growth in China’s oil consumption has been dramatic. Twenty years ago, China was East Asia’s largest oil exporter, but it became a net importer in 1994. In 2003, it became the world’s number three oil importer after the U.S. and Japan, and in 2005 it accounted for 31 per cent of global growth in oil demand.[8]

China’s quest for natural resources (including timber, oil, base metals as well as agricultural products) and overseas investment in support of meeting these needs have become frequent topics in the global media. China’s own consumption that drives the resource demand. For example, over half the value of China’s exports is derived from imported components and raw materials. A Stanford University study pointed out that the import value of Chinese exports to the U.S. is as high as 80 per cent (i.e., the products include a high level of materials imported to China, reprocessed into manufactured items).[9] This would imply that responsibility for sustainability and environmental concerns lies with consumers in the importing countries as well as with China, since the raw materials are taken from their own as well as other nations, and the final products are consumed outside of China. China has often been portrayed as responsible for negative global developments beyond its borders. However, in some cases (e.g., timber/furniture and cotton/textiles), it is not only China’s own consumption that drives the resource demand. For example, over half the value of China’s exports is derived from imported components and raw materials. A Stanford University study pointed out that the import value of Chinese exports to the U.S. is as high as 80 per cent (i.e., the products include a high level of materials imported to China, reprocessed into manufactured items).20 This would imply that responsibility for sustainability and environmental concerns lies with consumers in the importing countries as well as with China, since the raw materials are taken from their own as well as other nations, and the final products are consumed outside of China.

Trade, Investment and Expenditures Abroad

Recently, for the first time ever, China’s State Council in its Decision on Implementing the Scientific Concept of Development and Strengthening Environmental Protection,[10] called for more comprehensive attention to trade and environment issues, including Doha negotiations on trade and environment, refining environmental standards for exporting products, illegal waste imports and invasive alien species.

Expanded trade activities have contributed to China’s serious environmental problems including widespread air (Air pollution) and water (Water pollution) pollution, and serious ecological environmental damage. The level of damage is such that some international observers worry that China has become a very significant pollution haven. However, the evidence for this is mixed.[11] There are a number of specific studies covering environmental assessment (Environmental Impact Assessment) of China’s accession to the WTO.[12]

Increasingly, there is a focus on market supply chains, and the conditions under which resources are obtained by Chinese enterprises. A Global Witness report found that 90 per cent of timber crossing into China’s Yunnan from Myanmar’s Kachin State was illegal. China responded by signing an agreement with Myanmar to shut down this long-term trade.[13] Similarly, China and Indonesia signed an agreement to address problems of timber trade, but according to senior environmental officials in Indonesia, there has been limited followup. In fact, the “world’s biggest timber smuggling” was found between Indonesia and China.[14] A 2006 report by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) located in the U.K. indicated that China plays the leading role in the worldwide illegal trade in ozone destroying CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons).[15] These are only a few examples of trade and environment issues that China faces.

China worries about non-tariff trade barriers related to environment. In fact, this may be the most significant concern on the subject of trade and environment. The latest of these “green barriers” has raised concerns within China about its ability to export chemicals and products containing various chemicals. The EU has implemented a program intended to address some 30,000 chemicals which may have detrimental environmental and health affects. By June 2007, the REACH (Registration, Evaluation, and Authorization of Chemicals) Program will require registration of products with these chemicals. Apparently some five million Chinese products, including textiles, cosmetics and many other products, could be affected. At present there is no national system of chemical registration in China, and some 10 standards prevail. Billions of dollars of exports could be affected.[16] China also worries that the REACH Program will become a worldwide standard, therefore affecting its exports.

Bird flu is costing China and other countries billions of dollars. Some of the costs are directly related to movements of people and exported products. Increasingly these public health issues are linked to wildlife, and to disease epicentres in countries such as China. Invasive species (Alien species) directly affect China and other countries, causing significant economic and ecological damage. And trade involving rare or endangered species (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) is a well-established concern. There are environmental matters pertaining to novel life forms associated with biotechnology. All of these biodiversity-related aspects of trade are of growing significance globally and are of concern to China.

Beyond these specific cases, there are many huge and detailed tasks that need to be performed in order to introduce environmental considerations into trade policies and enforcement practices for China and other countries, and within the trade agreements themselves. Most importantly, there is the need to build a better understanding and approach to trade and sustainable development— focused more broadly than on trade and environment considerations.

Integrated Trade and Sustainable Development Strategy

CCICED’s influential Trade and Environment Working Group and Task Forces[17] advocated for years that an overall national strategy for sustainable foreign trade, a green trade action plan and an integrated investment policy should be developed and implemented by the Chinese government in order to better promote trade and sustainable development. Although some progress has been made in some sectors and on specific issues, there is no coherent action. The lack of such a coherent policy, higher priorities paid to GDP and trade growth, and the absence of the necessary institutional coordination are hindering the development of a sustainable trade strategy.

The State Council’s major 2005 Decision for strengthening environmental protection and follow-up, such as the “Three Transformations” described earlier, calls for the coordination of socio-economic growth with environmental protection; putting environment at a more important strategic position; and reinforcing leadership on environmental protection work. The emphasis is on accountability, with principal officials of relevant departments and local governments held responsible for environmental protection work in their jurisdictions. This represents an unprecedented opportunity for developing integrated trade and sustainable development strategies, with accountability on the part of both trade and environment departmental officials.

Investment at Home and Abroad

Investment is important for sustainable development. High-quality and well-managed foreign investment at national and international levels can help promote the move from unsustainable to sustainable practices in various sectors. During the 11th Five-Year Plan period, China’s goals are to continue to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) vigorously; to improve its investment law and policy; and to guide the FDI flow—to high-tech, to the high-end of production, to environmentally-friendly processes and production methods, and to China’s inland and western regions. As China moves to becoming one of the world’s leading investors in scientific R&D (likely second only to the U.S., or perhaps third), a significant portion of the investment will be devoted to environmental protection. This may help to overcome a significant problem in creating “Made in China” solutions well-suited to local environmental, social and economic circumstances, and also a means of overcoming the intellectual property rights (IPR) issues that make it difficult for China to engage in technology leapfrogging, and to gain access to leading-edge environmental solutions.

Recently, Chinese companies have actively engaged in overseas acquisition activities all over the world in an effort to acquire a wide range of natural resources to meet the short supply at home. In 2005, direct investment abroad by Chinese firms increased by 27 per cent to US$3.2 billion, and contracted overseas investment jumped by 78 per cent to US$3.71 billion. More than half of 2005’s overseas direct investment by China was in the mining sector.[18] While this level of Chinese international investment pales in comparison to the US$60 billion invested in China by foreign firms in 2005, it represents the beginning of a new trend where Chinese state-owned and private enterprises will be more active in establishing a global presence supported by the Chinese government. This trend will include partial or complete purchase of banks and perhaps other financial firms abroad.

In 2002, the Chinese leadership announced at the 16th National Party Congress a broad “going out” strategy for both state-owned and private companies. In 2003, the government focused on commodities and adopted a policy to promote and protect investments in mineral resources prospecting and exploitation outside China. The 11th Five-Year Plan calls for further implementations of the “going out” strategy, and will provide support to enterprises that have the ability to engage in overseas operation and overseas acquisition, particularly resource exploitation and development cooperation to meet government policy objectives of securing commodities.

It is important that Chinese companies with an interest in overseas investment are aware of private and public opposition to the so-called “race to the bottom” on environmental measures and of corporate responsibility in their overseas acquisition efforts. Recent events in North America and elsewhere suggest that Chinese businesses may well benefit from stronger and sounder investment treaties. Private and government opposition in the United States ultimately prevented the proposed acquisition of Unocal by China’s National Petroleum Corporation. China’s Minmetals’s potential interest in acquiring Noranda, a major Canadian resource company, also provoked some vocal opposition in Canada raising issues such as poor management, lower global standards of transparency, environmental standards and corporate responsibility of Chinese state-owned enterprises.

China has concluded bilateral investment treaties with some 71 countries over the past 25 years. Most of these agreements are modelled on the current international investment model developed a half century ago. Chinese interest in investments in the national resources sector outside of China may well benefit from a comprehensive and robust international investment regulatory regime that promotes sustainable development at national and international levels. However, there is no strong push in this direction from China.

International investment agreements (IIAs) have now become an important part of the legal and policy mechanisms that govern the economic processes of globalization. To put it more simply, international investment agreements are all about the governance of globalization.[19] The current international investment regime developed 50 years ago is inherently flawed and can no longer meet the needs of the [[global] economy] in the 21st century. It only focuses on the protection of foreign capital and investments; and the arbitration process developed to address disputes primarily focusing on investor-state arbitrations has major flaws. Also, international investment agreements grew on a bilateral basis between home and host states; there is no international institutional home for IIAs. This is clearly a topic that should be of interest to China and to its main trading partners. It is an example of the fundamental weaknesses of the international legal structure in matters affecting environment and other significant impacts.

International Cooperation Roles

China’s has clearly signaled its intention to take an active part in many types of international cooperation related to environment and development. The following areas represent some of the more important possibilities:

- Active participation in the negotiation, funding and action internationally of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) and environmental aspects of other international agreements for health, trade, etc.

- Building domestic implementation capacity for MEAs signed and ratified by China, including new or revised laws and regulations, strengthened policies and enforcement.

- Increasing the level of Chinese participation concerning environment and development in international organizations.

- Ensuring effective implementation of bilateral and multilateral agreements for managing shared resources (e.g., “Top of the world” mountain regions in western China; water resources in border regions such as Mekong and Songhua Rivers; and the South China and Bohai Seas).Promoting a good level of corporate governance capacity, and corporate social responsibility of Chinese businesses operating in China and/or internationally.

- Creating transparent processes for information sharing on resource and environmental problems, infectious diseases, etc., with consumers, organizations and governments internationally and within China. An example is China’s willingness to undergo examination of its environmental protection mechanisms and organization by the [[for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)|OECD)).[20]]</sup></span>

- Sharing of Chinese experience in environmental technology and protection with other nations, including via Chinese development assistance.

- Expansion of joint efforts with foreign governments, universities and research organizations to address issues of mutual concern within China and internationally.

This list undoubtedly will be expanded in the future, as new problems emerge globally and as Chinese presence becomes greater in international environmental initiatives. China has ratified dozens of international environmental agreements, amendments and protocols. The national environmental protection law has taken the position that when domestic law is not in accordance with an international environmental accord ratified or acceded to by China, then the provisions of the international convention should be implemented, except in those cases where China had specified its reservations.[21] One persistent concern internationally is how China can contribute to a strengthening of global environmental governance, and why it might be in China’s best interest to do so.

What might China do to ensure that its interests are better served through a strengthened global environmental governance system? First, actions speak louder than words. China can meet its own rigorous domestic targets for energy efficiency and pollution control; restrict activities such as the import of illegally-cut timber; and ensure that its companies investing or operating abroad also observe good environmental standards. In these ways, China will contribute to improved global environmental quality, and build a reputation for itself as a respected and responsible world citizen in regard to environment and development. China can implement internationally recognized best practices, including investment in newer technologies domestically, and seek cooperation with others to ensure these practices operate smoothly. This is particularly needed in coal technology, where China’s practices significantly affect global environmental quality.

China cannot delay taking a larger role in world environmental affairs. It is now a major economic power, a key player in energy, greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. And it is reshaping the world’s market supply chains. Thus China should have a strong vested interest in creating predictable international environmental rules under which its businesses operate, and under which its own goods and services are traded. At the moment these are only weakly developed. There are many ways to enhance its role, ranging from pressing for enhanced action on existing agreements where these are compatible with Chinese needs, to scientific and other cooperation to produce better monitoring and environmental knowledge, and through expanding Chinese participation within international bodies, including financial support.

China also might build on the success it has had in domestic implementation of some global voluntary efforts for environment such as the widespread adoption of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 management standards. Fully embracing other approaches such as the Responsible Care Programs used in chemical and other sectors internationally would help to meet China’s own “circular economy” objectives.[22] Over the longer term, China and other fast-growing major nations such as India and Brazil may have considerable influence in shaping the organization and effectiveness of the still relatively young global environmental governance structure into a more functional system. Certainly other nations already recognize the major influence these and other large countries are having on the world's environment and development. Needed are very clear signals of innovation and success in addressing the problems. This will create a level of credibility with both richer and poorer nations that such problems can be tackled while continuing ambitious economic and social development efforts.

Environment and Security Matters

The notion of considering environment and development as a security concern is relatively new but of growing interest internationally and nationally.[23] It is derived from an expanded definition of security that focuses attention on both human development and ecological conditions, and on security of resource supply and ecological services. Thus factors such as climate change, environmental incidents, such as large oil spills or prolonged periods of drought, floods and other natural disasters, can be considered as threats to human security, and to both natural and highly managed ecosystems. A general matter of concern for many countries, including China, is security of food, energy and raw materials for manufacturing. These might be considered as factors of economic security. Poverty, environment and security is another approach of considerable concern, especially in regions of scarce land and water resources, where roots of conflict arise from access to resources and from environmental degradation. And, of course, there are those who would place environment and resource considerations into the framework of traditional military security, for example, refugees from civil strife over matters such as water and land use conflicts, and, internationally, military interventions to safeguard market supply chains for oil or other natural resources.

Another way of thinking about environment and security is that it brings out the potential of examining problems from an adaptive, sustainable development approach rather than from an ordered response approach. The latter employs solutions based on either use of military power or blunt instruments such as economic structural adjustment to address serious problems. Environment and security are only beginning to be linked in the case of China’s environment and development.[24]

In China’s global relationships, as analyzed by some Western academics and those interested in new aspects of foreign affairs, the following topics are examples concerning environment and security. It should be noted that while some of these topics can be related directly to matters beyond China’s borders, in other cases, there is concern for insecurity within China including political, economic and social implications.

- Domestic destabilizing influences of conflict over [[pollution] incidents and improper land appropriation. Impacts on China’s ecosystems, water and food production arising from climate change.

- Impacts on fisheries and ecosystems arising from uncontrolled/unregulated exploitation in disputed areas of the South China Sea.

- Impacts of air (Air pollution) pollutants from Asia (including China) such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals on food chains for people and wildlife in Arctic areas.

- Purchase of natural resources such as oil or timber from countries with governments considered likely to be repressive or with a poor record of environmental sustainability.

- Purchase of natural resources such as agricultural commodities, timber, oil or minerals where the result may be incursion into globally significant ecosystems, or onto lands from where indigenous people may be displaced (e.g., the Amazon, parts of Africa).

- Human, plant and animal diseases and invasive species (Alien species) that are transformative in their economic, social or environmental impact. Trade, travel of people and other mixing factors constitute threats to environmental security, although providing essential benefits.

The subject of environment and security related to China will grow in significance over coming years, although these relationships require more analysis and statements need to be carefully considered, not blindly accepted.

Notes

This is a chapter from One Lifeboat: China and the World's Environment and Development (e-book). Previous: Chapter 1: Rising Interdependency (One Lifeboat: Chapter 2) (One Lifeboat: Chapter 2) |Table of Contents|Next: Chapter 3: Case Studies (One Lifeboat: Chapter 2)