Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment

This is Section 3.2 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Authors: Henry Huntington, Shari Fox; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Igor Krupnik; Consulting Authors: Anne Henshaw,Terry Fenge, Scot Nickels, Simon Wilson

Indigenous peoples have long depended on their knowledge and skills for survival, including their ability to function in small, independent groups by dividing labor and maintaining strong social support and mutual ties both within and between their immediate communities[1]. Knowledge about the environment is equally important. Understanding the patterns of animal behavior and aggregation is necessary for acquiring food. Successful traveling and living in a cold-dominated landscape requires the ability to read subtle signs in the ice, snow (Snow cover in the Arctic), and weather. Gradual shifts in social patterns and environmental conditions make this a continuous process of learning and adapting. In the past, sudden shifts in physical conditions, such as abrupt warming or cooling, led to radical changes including the abandonment of large areas for extended periods that is apparent from the archeological record[2]. Knowing one’s surroundings was an often-tested requirement, one that remains true today for those who travel on and live off the land and sea[3].

Contents

Academic engagement with indigenous knowledge (3.2.1)

Those outside indigenous communities have not always recognized or respected the value of this knowledge. Occasionally used and less frequently credited prior to and during most of the twentieth century, indigenous knowledge from the Arctic has received increasing attention over the past couple of decades[4]. This interest, arising from research in the ethnosciences, has taken the form of studies to document indigenous knowledge about various aspects of the environment[5], the increasing use of cooperative approaches to wildlife and environmental management[6], and a greater emphasis on collaborative research between scientists and indigenous people[7]. This section describes some of the characteristics of indigenous knowledge and its relevance for studies of climate change and its implications.

The topic of indigenous knowledge is not without disputes and controversy. In fact, agreement has not even been found on the appropriate term – "traditional knowledge", "traditional ecological knowledge", "traditional knowledge and wisdom", "local and traditional knowledge", "indigenous knowledge", and various combinations of these words and their acronyms are among those that have been used[8]. Terms specific to particular peoples are also common, such as "Saami knowledge" or "Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit". Although their definitions largely overlap, each raises difficulties. The term "indigenous" in this context excludes long-term arctic residents not of indigenous descent, implies that all indigenous persons hold this knowledge, and emphasizes ancestry over experience. "Traditional" has a connotation of being static and from past times, whereas this knowledge is current and dynamic. "Local" fails to capture the sense of continuity and the practice of building on what was learned by previous generations. "Knowledge" by itself omits the insights learned from experience and application, which are better captured by "wisdom". All of these terms neglect the spiritual dimensions of knowledge and connection with the environment that are often of greatest importance to those who hold this knowledge. Some groups, such as the World Intellectual Property Organization, identify "indigenous knowledge" as a subset of "traditional knowledge", with the latter incorporating folklore[9]. The issue of terminology will not be resolved here, but the term "indigenous knowledge" is used in a broad sense, encompassing the various systems of knowledge, practice, and belief gained through experience and culturally transmitted among members and generations of a community[10].

By any term, indigenous knowledge plays a vital role in arctic communities, and its perpetuation is important to the future of such communities. It has also become a popular research topic. Scholars within and outside the indigenous community discuss its nature, the appropriate ways in which it should be studied and used, how it can be understood, and how it relates to other ways of knowing such as the scientific. Many agree that indigenous knowledge offers great insight from people who live close to and depend greatly on the local environment and its ecology[11]. Most of these scholars also recognize, however, that gaining access to and using this knowledge must be done with respect for community rights and interests, and with awareness of the cultural contexts within which the knowledge is gathered, held, and communicated[12]. Successful efforts are typically built on trust and mutual understanding. It takes time for knowledge holders to feel comfortable sharing what they know, for researchers to be able to understand and interpret what they see and hear, and for both groups to understand how indigenous knowledge is represented and for what purpose.

The legal and political contexts of indigenous knowledge (Incorporating traditional knowledge in the Arctic) must also be taken into account. The intellectual property aspects of indigenous knowledge are being explored[13]. Some jurisdictions in the Arctic require that it be considered in processes such as resource management and environmental impact assessment[14]. Throughout the Arctic, there is increasing political pressure to use indigenous knowledge, but often without clear guidance on exactly how this should be achieved. Most existing ethical guidelines or checklists for community involvement in research identify the areas to be addressed in research agreements, but do not resolve how the controversial questions are best answered[15]. Such uncertainty may lead to reluctance on the part of some researchers to engage in studies of indigenous knowledge, but at present there are many good examples of collaborative projects that have benefited both the communities involved and those conducting the research[16].

The development and nature of indigenous knowledge (3.2.2)

Careful observation of the world combined with interpretation in various forms is the foundation for indigenous knowledge[17]. The ability to thrive in the Arctic depends in large part on the ability to anticipate and respond to dangers, risks, opportunities, and change. Knowing where caribou are likely to be is as important as knowing how to stalk them. Sensing when sea ice (Sea ice in the Arctic) is safe enough for travel is an essential part of bringing home a seal. The accuracy and reliability of this knowledge has been repeatedly subjected to the harshest test as people’s lives have depended on decisions made on the basis of their understanding of the environment. Mistakes can lead to death, even for those with great experience. Thus, information of particular relevance to survival has been valued and refined through countless generations, as individuals combine the lessons of their elders with personal experience[18].

Indigenous knowledge is far more than a collection of facts. It is an understanding of the world and of the human place in the world[19]. From observations, people everywhere find patterns and similarities and associations, from which they develop a view of how the world works, a view that explains the mysteries surrounding them, that gives them a sense of place[20]. In the Arctic, parallels may be drawn, for example, in the migrations of caribou, cranes, and whales[21]. Systems of resource use are developed to make efficient use of available resources[22]. Hunters develop rituals and practices that reflect their view of the world[23]. Stories, dances, songs, and artwork express this worldview[24]. In turn, culture shapes perception, and the world is interpreted according to the way it is understood. When personal memories and stories are retold to family members, relatives, neighbors, and others, as is common practice across the Arctic, an extensive local record is built. Non-verbal transmission of knowledge and skills, for example through observation and imitation, is also common. It often extends over several generations and represents the accumulated knowledge of many highly experienced and respected persons. Learning the knowledge of one’s people involves absorbing the stories and lessons, then watching closely to figure out exactly what is meant and how to use it, and adapting it to one’s own needs and experiences. In these ways, indigenous knowledge is continually evolving[25].

The use and application of indigenous knowledge (3.2.3)

Studies of indigenous knowledge often make comparisons with scientific knowledge in an effort to determine the "accuracy" of indigenous knowledge as measured on a scale that is intended to be objective. Other studies use indigenous knowledge in the generation of new hypotheses or for the identification of geographic locations for research[26]. While this can be worthwhile, the value of indigenous knowledge lies primarily within the group and culture in which it developed. Holders of this knowledge use it when making decisions or in setting priorities, and an understanding of the nature of this knowledge can help explain the rationale behind these processes[27]. "Accuracy" in this context depends on the uses to which the knowledge is put, not on an external evaluation.

The emphasis on the cultural aspects of indigenous knowledge (Incorporating traditional knowledge in the Arctic) in this assessment is not intended to detract from the great utility it has in ecological and environmental research and management[28]. In this setting, accuracy as evaluated externally may be a key concern because the information is being applied for a purpose that may be very different from that for which it was originally generated. There are many instances where indigenous knowledge of the habits of an animal such as the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) [29] or the interactions within an ecosystem such as sea-ice (Sea ice effect on marine systems in the Arctic) phenomena[30] were – and are – far in advance of scientific understanding, and in fact were used by scientists to make significant progress in ecology and biology[31]. This is especially true in the Arctic, where scientific inquiry is a relatively recent phenomenon, and where researchers often depend on the knowledge and skills of their indigenous guides.

To apply indigenous knowledge to environmental research and management, consideration must be given to the ways in which it is acquired, held, and communicated. Indigenous knowledge is the synthesis of innumerable observations made over time[32]. Added weight is often given to anomalous occurrences, in order to be better prepared for surprises and extremes. It is typically qualitative; when quantities are noted, they are more often relative than absolute. Indigenous knowledge evolves with changing social, technological, and environmental conditions[33], and thus observations of change over time can be influenced by these as well as by the vagaries of memory. Indeed, one of the main challenges in evaluating observations of environmental change is that of addressing the many factors that influence the ways in which people remember and describe events. In addition, some communities today are experiencing erosion of indigenous knowledge and the esteem in which it is held, which has emotional and practical impacts on individuals and communities[34].

Indigenous knowledge has been documented on various topics in various places in the Arctic, largely in North America. These efforts have rarely focused on climate change or even included climate change as an explicit topic of discussion. Nonetheless, substantial information is available, including evidence from place names (see Box 3.2 below) and the archaeological record (See Box 3.3 below). Further documentation is highly desirable, both for increasing the understanding of climate dynamics and as a means of engaging arctic residents in the search for appropriate responses to the impacts of climate change.

|

Box 3.2. Place names as indicators of environmental change Indigenous peoples use a variety of cultural mechanisms to pass on climatic and environmental knowledge and its “attendant adaptive behavior” from one generation to the next (Gunn, 1994; Henshaw, 2003).These mechanisms include place names, which reflect perceptions of the environment and can serve as a repository for accumulated knowledge. When conditions change, place names can serve as indicators of environmental change. Place names show how perceptions of physical geography, ecology, and climate transform observations and experiences to memory shared among members of a particular group[35]. As environmental conditions change, place names (or toponyms) may change or persist, providing insight into the nature of those changes and the adaptations that accompany them. For example, near Iqaluit, Nunavut, there is a site called Pissiulaaqsit, which translates as “a place where there is an absence of guillemots” [36]. Local residents explain that the name is significant because guillemots nested there in the past. In the Sikusilarmiut land-use area, covering most of the Foxe Peninsula in Nunavut, Henshaw[37] has documented more than 300 toponyms around the community of Kinngait (Cape Dorset).The extensive naming of places, often using descriptive terms, creates an important frame of reference for navigation, with crucial implications for safety, travel, and hunting. Many of the place names refer to features or phenomena that may be highly sensitive to environmental change. For example, Ullivinirkallak is a place that used to be used for storing walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) meat.That it is no longer used for that purpose may indicate change to permafrost. Qimirjuaq is a large plateau with ice and snow even in summer.The area watered by melting snow produces abundant berries, and so the size and condition of the snowfield is monitored closely.The berry pickers quickly note changes in the persistence and characteristics of the snowfield. Seasonal features such as polynyas or migratory routes are also named, as are patterns of currents and sea-ice movements. Documenting these names and the conditions that occur at these locations can provide a means of monitoring and identifying future environmental change. |

|

Box 3.3.Archaeology and past changes in the arctic climate The documentation of indigenous observations of climate change has focused primarily on recent decades. But the arctic environment has long been recognized for its extreme variability and rapid fluctuations. Several past examples of both extreme warming and cooling events are documented in Chapter 2 (Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment). In addition to the work by climatologists and physical scientists, social scientists, archaeologists, and ethnohistorians have accumulated a large body of evidence concerning past changes in the environment.They often use proxy data, such as rapid shifts in human subsistence practice, change in settlement areas, substantial population moves, or certain migration patterns, as indicators of rapid transitions in arctic ecosystems. Since the 1970s, archaeologists have developed detailed scenarios of how past climate changes have affected human life, local economies, and population distribution within the Arctic. One of the clearest examples of such links was the expansion of indigenous bowhead whaling and the rapid spread of the whaling-based coastal Eskimo cultures from northern Alaska across the central Canadian Arctic to Labrador, Baffin Island, and eventually to Greenland around 1000 years ago. Based upon recent radiocarbon dating and paleoenvironmental data, this enormous shift in population and economy took place within less than 200 years, caused at least in part by the rapidly changing sea-ice and weather conditions in the western and central Arctic[38].When around 300 to 400 years later the arctic climate shifted to the next cooling phase, Inuit were forced to abandon whaling over most of the central Canadian Arctic.This extreme cooling trend around 400 to 500 years ago left many Inuit communities isolated and under heavy environmental stresses that triggered population declines and loss of certain subsistence skills and related knowledge. One well-known example of these impacts illustrates that not all responses are effective, and that people may not be able to adapt to all types of change.The Polar Eskimo (Inughuit) of northwest Greenland lost the use of their skin hunting boats (kayaks), bows and arrows, and fish spears when they became isolated from other communities by expanded glaciers and heavier sea ice during the Little Ice Age. In consequence, open water hunting for seals and walruses declined, and hunting for caribou and ptarmigan (Lagopus spp.) was completely abandoned, to the extent that their meat was considered unfit for human consumption[39]. As game animals were labeled “unclean” or “unreachable”, the whole body of related expertise about animal habits, observation practices, the pursuit and capture of animals, and the butchering and storing of meat was reduced dramatically or completely lost. Some shifts of this kind, as well as stories about hardship caused by environmental change, have been preserved in indigenous oral traditions, folklore, and myths[40]. However, few systematic attempts have been made so far to use indigenous knowledge to track historical or pre-historical cases of arctic climate change. |

3.1. Introduction (Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment)

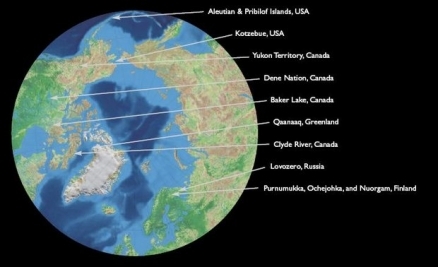

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Indigenous knowledge of the Arctic environment. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Indigenous_knowledge_of_the_Arctic_environment- ↑ Burch, E.S. Jr., 1998. The Inupiaq Eskimo nations of northwest Alaska. University of Alaska, xviii + 473p.–Krupnik, I., 1993. Arctic Adaptations: Native Whalers and Reindeer Herders of Northern Eurasia. University Press of New England, xvii + 355p.–Freeman, M.M.R. (ed.), 2000. Endangered Peoples of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive. The Greenwood Press, xix + 278p.–Usher, P.J., G. Duhaime and E. Searles, 2003. The household as an economic unit in Arctic aboriginal communities, and its measurement by means of a comprehensive survey. Social Indicators Research, 61(2):175–202.

- ↑ Fitzhugh, W. W., 1984. Paleo-Eskimo cultures of Greenland. In: D. Damas (ed.). Arctic. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 5, pp.528–539. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.–McGhee, R., 1996. Ancient People of the Arctic. University of British Columbia Press, xii + 244p.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke, 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1251–1262.–Fox, S., 1998. Inuit Knowledge of Climate and Climate Change. M. A. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Canada.–Huntington, H.P., J.H. Mosli and V.B. Shustov, 1998. Peoples of the Arctic: characteristics of human populations relevant to pollution issues. In: AMAP Assessment Report: Arctic Pollution Issues, pp. 141–182. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo.–Inglis, J. T. (ed.), 1993. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases. International Program on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, 142p.–Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.

- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R., (ed.), 1976. Report of the Inuit land use and occupancy project. 3 vols. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.–Inglis, J. T. (ed.), 1993. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases. International Program on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, 142p.–Nadasdy, P., 1999. The politics of TEK: power and the "integration" of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 36(1):1–18.–Stevenson, M.G., 1996. Indigenous knowledge and environmental assessment. Arctic, 49(3):278–291.

- ↑ Ferguson, M. A.D. and F. Messier, 1997. Collection and analysis of traditional ecological knowledge about a population of arctic tundra caribou. Arctic, 50(1):17–28.–Fox, S., 2002. These are things that are really happening: Inuit perspectives on the evidence and impacts of climate change in Nunavut. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 12–53. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.–Huntington, H.P. and the communities of Buckland, Elim, Koyuk, Point Lay and Shaktoolik, 1999. Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the eastern Chukchi and northern Bering seas, Alaska. Arctic, 52(1):49–61.–Kilabuck, P., 1998. A Study of Inuit Knowledge of Southeast Baffin Beluga. Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, Iqaluit, Northwest Territories, iv + 74p.–McDonald, M., L. Arragutainaq and Z. Novalinga, 1997. Voices from the Bay: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the James Bay Bioregion. Canadian Arctic Resources Committee and Environmental Committee of the Municipality of Sanikiluaq, Ottawa, 90p.–Mymrin, N.I., the communities of Novoe Chaplino, Sireniki, Uelen, and Yanrakinnot and H.P. Huntington, 1999. Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the northern Bering Sea, Chukotka, Russia. Arctic, 52(1):62–70.–Riedlinger, D. and F. Berkes, 2001. Contributions of traditional knowledge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Record, 37(203):315–328.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1998. Indigenous knowledge and resource management systems in the Canadian subarctic. In: F. Berkes and C. Folke (eds.). Linking Social and Ecological Systems, pp. 98–128. Cambridge University Press.–Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Freeman, M.M.R. and L.N. Carbyn (eds.), 1988. Traditional Knowledge and Renewable Resource Management in Northern Regions. Boreal Institute for Northern Studies, Alberta, 124p.–Huntington, H.P., 1992a. The Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and other cooperative marine mammal management organizations in Alaska. Polar Record, 28(165):119–126.–Huntington, H.P., 1992b. Wildlife management and subsistence hunting in Alaska. Belhaven Press, xvii + 177p.–Pinkerton, E. (ed.), 1989. Cooperative Management of Local Fisheries. University of British Columbia Press, xiii + 299p.–Usher, P.J., 2000. Traditional ecological knowledge in environmental assessment and management. Arctic, 53(2):183–193.

- ↑ Huntington, H.P., 2000a. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1270–1274.–Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.

- ↑ Huntington, H.P., 1998. Observations on the utility of the semi-directive interview for documenting traditional ecological knowledge. Arctic, 51(3):237–242.–Kawagley, A.O., 1995. A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit. Waveland Press, 166p.–Turner, N.J., M. Boelscher Ignace and R. Ignace, 2000. Traditional ecological knowledge and wisdom of aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1275–1287.

- ↑ WIPO, 2001. Intellectual property needs and expectations of traditional knowledge holders. World Intellectual Property Organization, Geneva.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Huntington, H.P., 1998. Observations on the utility of the semi-directive interview for documenting traditional ecological knowledge. Arctic, 51(3):237–242.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1998. Indigenous knowledge and resource management systems in the Canadian subarctic. In: F. Berkes and C. Folke (eds.). Linking Social and Ecological Systems, pp. 98–128. Cambridge University Press.–Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Freeman, M.M.R. and L.N. Carbyn (eds.), 1988. Traditional Knowledge and Renewable Resource Management in Northern Regions. Boreal Institute for Northern Studies, Alberta, 124p.–Huntington, H.P., 2000a. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1270–1274.–Inglis, J. T. (ed.), 1993. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases. International Program on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, 142p.–Mailhot, J., 1993. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: The Diversity of Knowledge Systems and Their Study. Great Whale Public Review Support Office, Montreal, 48p.

- ↑ Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.–Wenzel, G., 1999. Traditional ecological knowledge and Inuit: reflections on TEK research and ethics. Arctic, 52(2):113–124.

- ↑ WIPO, 2001. Intellectual property needs and expectations of traditional knowledge holders. World Intellectual Property Organization, Geneva.

- ↑ Smith, D., 2001. Co-management in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. In: Arctic Flora and Fauna: Status and Trends, pp. 64–65. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Helsinki.

- ↑ Grenier, L., 1998. Working with indigenous knowledge: a guide for researchers. International Development Research Center, Ottawa, 115p.–IARPC, 1992. Principles for the conduct of research in the Arctic. Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee, Arctic Research of the United States, 6:78–79.

- ↑ Huntington, H.P. and the communities of Buckland, Elim, Koyuk, Point Lay and Shaktoolik, 1999. Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the eastern Chukchi and northern Bering seas, Alaska. Arctic, 52(1):49–61.–Huntington, H.P., P.K. Brown-Schwalenberg, M.E. Fernandez-Gimenez, K.J. Frost, D. W. Norton and D.H. Rosenberg, 2002. Observations on the workshop as a means of improving communication between holders of traditional and scientific knowledge. Environmental Management, 30(6):778–792.–Kilabuck, P., 1998. A Study of Inuit Knowledge of Southeast Baffin Beluga. Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, Iqaluit, Northwest Territories, iv + 74p.–McDonald, M., L. Arragutainaq and Z. Novalinga, 1997. Voices from the Bay: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the James Bay Bioregion. Canadian Arctic Resources Committee and Environmental Committee of the Municipality of Sanikiluaq, Ottawa, 90p.

- ↑ Cruikshank, J., 2001. Glaciers and climate change: perspectives from oral tradition. Arctic, 54(4):377–393.–Huntington, H.P., 2000a. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1270–1274.–Johnson, M. (ed.), 1992. Lore: capturing traditional environmental knowledge. Dene Cultural Institute and International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, 190p.–Kilabuck, P., 1998. A Study of Inuit Knowledge of Southeast Baffin Beluga. Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, Iqaluit, Northwest Territories, iv + 74p.–Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.

- ↑ Ingold, T. and T. Kurtilla, 2000. Perceiving the environment in Finnish Lapland. Body and Society, 6(3?4):183–196.

- ↑ Agrawal, A., 1995. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Development and Change, 26(3):413–439.–Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke, 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1251–1262.–Fehr, A. and W. Hurst (eds.), 1996. A seminar on two ways of knowing: indigenous and scientific knowledge. Aurora Research Institute, Inuvik, Northwest Territories, 93p.–Kawagley, A.O., 1995. A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit. Waveland Press, 166p.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Brody, H., 2000. The other side of Eden: hunters, farmers and the shaping of the world. Douglas & McIntyre, 368p.–Nelson, R.K., 1983. Make prayers to the raven. University of Chicago Press, xvi + 292p.

- ↑ Huntington, H.P. and the communities of Buckland, Elim, Koyuk, Point Lay and Shaktoolik, 1999. Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the eastern Chukchi and northern Bering seas, Alaska. Arctic, 52(1):49–61.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1998. Indigenous knowledge and resource management systems in the Canadian subarctic. In: F. Berkes and C. Folke (eds.). Linking Social and Ecological Systems, pp. 98–128. Cambridge University Press.–Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke, 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1251–1262.

- ↑ Cruikshank, J., 1998. The social life of stories: narrative and knowledge in the Yukon Territory. University of Nebraska Press, xvii + 211p.–Fienup-Riordan, A., 1994. Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. University of Oklahoma Press, xxiv + 389p.

- ↑ Cruikshank, J., 1998. The social life of stories: narrative and knowledge in the Yukon Territory. University of Nebraska Press, xvii + 211p.

- ↑ Ingold, T. and T. Kurtilla, 2000. Perceiving the environment in Finnish Lapland. Body and Society, 6(3?4):183–196.

- ↑ Albert, T.F., 1988. The role of the North Slope Borough in Arctic environmental research. Arctic Research of the United States, 2:17–23.–Huntington, H.P., 2000a. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1270–1274.–Johannes, R.E., 1993. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge and management with environmental impact assessment. In: J. T. Inglis (ed.). Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases, pp. 33–39. International Program on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and International Development Research Centre, Ottawa.–Nadasdy, P., 1999. The politics of TEK: power and the "integration" of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 36(1):1–18.–Riedlinger, D. and F. Berkes, 2001. Contributions of traditional knowledge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Record, 37(203):315–328.

- ↑ Cruikshank, J., 1981. Legend and landscape: convergence of oral and scientific traditions in the Yukon Territory. Arctic Anthropology, 18(2):67–94.–Cruikshank, J., 1998. The social life of stories: narrative and knowledge in the Yukon Territory. University of Nebraska Press, xvii + 211p.–Feldman, K.D. and E. Norton, 1995. Niqsaq and napaaqtuq: issues in Inupiaq Eskimo life-form classification and ethnoscience. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 19(2):77–100.–Kublu, A., F. Laugrand and J. Oosten, 1999. Introduction. In: J. Oosten and F. Laugrand (eds.), pp. 1–12. Interviewing Inuit elders. Vol. 1. Iqaluit: Nunavut Arctic College.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1998. Indigenous knowledge and resource management systems in the Canadian subarctic. In: F. Berkes and C. Folke (eds.). Linking Social and Ecological Systems, pp. 98–128. Cambridge University Press.–Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor & Francis, xvi + 209p.–Fox, S., 2004. When the Weather is Uggianaqtuq: Linking Inuit and Scientific Observations of Recent Environmental Change in Nunavut, Canada. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Colorado.–Freeman, M.M.R. and L.N. Carbyn (eds.), 1988. Traditional Knowledge and Renewable Resource Management in Northern Regions. Boreal Institute for Northern Studies, Alberta, 124p.–Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.–Riedlinger, D. and F. Berkes, 2001. Contributions of traditional knowledge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Record, 37(203):315–328.

- ↑ Albert, T.F., 1988. The role of the North Slope Borough in Arctic environmental research. Arctic Research of the United States, 2:17–23.

- ↑ Norton, D. W., 2002. Coastal sea ice watch: private confessions of a convert to indigenous knowledge. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 126–155. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R., 1992. The nature and utility of traditional ecological knowledge. Northern Perspectives, 20(1):9–12.–Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.

- ↑ Agrawal, A., 1995. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Development and Change, 26(3):413–439.– Huntington, H.P., 1998. Observations on the utility of the semi-directive interview for documenting traditional ecological knowledge. Arctic, 51(3):237–242.

- ↑ Krupnik, I. and N. Vakhtin, 1997. Indigenous knowledge in modern culture: Siberian Yupik ecological legacy in transition. Arctic Anthropology, 34(1):236–252.

- ↑ Fox, S., 2002. These are things that are really happening: Inuit perspectives on the evidence and impacts of climate change in Nunavut. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 12–53. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Cruikshank, J., 1990. Getting the words right: perspectives on naming and places in Athapascan oral history. Arctic Anthropology, 27(1):52–65.Müller-Wille, L., 1983. Inuit toponymy and cultural sovereignty. In: L. Müller-Wille (ed.). Conflict in the Development in Nouveau-Quebec, pp. 131–150. Centre of Northern Studies and Research at McGill University, Montreal;Müller-Wille, L., 1985. Une methodologie pour les enuêtes toponymiques autochtones: le répertoire Inuit de la region de Kativik et de sa zone côtière. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 9(1):51–66;Peplinski, L., 2000. Public resource management and Inuit toponymy: implementing policies to maintain human-environmental knowledge in Nunavut. M.A.Thesis, Royal Roads University, British Columbia;Rankama,T., 1993. Managing the landscape: a study of Sami place names in Utsjoki, Finnish Lapland. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 17(1):47–67.

- ↑ Peplinski, 2000, Op. cit.

- ↑ Henshaw, A., 2003. Climate and culture in the North: The interface of archaeology, paleoenvironmental science and oral history. In: S. Strauss and B. Orlove (eds.).Weather, Climate, Culture. Berg Press.

- ↑ Bockstoce, J.R., 1976. On the development of whaling in the Western Thule Culture. Folk, 18:41–46;-Maxwell, M.S., 1985. Prehistory of the Eastern Arctic. Academic Press;-McCartney, A.P. and J.M. Savelle, 1985.Thule Eskimo whaling in the central Canadian Arctic. Arctic Anthropology, 22(2):37–58.;-McGhee, R., 1969/70. Speculations on climatic change and Thule Culture development. Folk, 11–12:173–184;-McGhee, R., 1984.Thule prehistory of Canada. In: D. Damas (ed.). Arctic. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 5, pp. 369–376, Smithsonian Institution,Washington, D.C.-Stoker, S. and I.I. Krupnik, 1993. Subsistence whaling. In: J.J. Burns, J.J. Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.).The Bowhead Whale, pp. 579–629.The Society for Marine Mammalogy, Kansas.;-Whitbridge, P., 1999.The prehistory of Inuit and Yupik whale use. Revista de Arqueologia Americana, 16:99–154.

- ↑ Gilberg, R., 1974–75. Changes in the life of the polar Eskimos resulting from a Canadian immigration into the Thule District, North Greenland in the 1860s. Folk, 16–17:159–170;-Gilberg, R., 1984. Polar Eskimo. In: D. Damas (ed.). Arctic. Handbook of North American Indians vol. 5, pp. 577–594. Smithsonian Institution,Washington D.C.;-Mary-Rousselière, G., 1991. Qitdlarssuaq:The Story of a Polar Migration.Wuerz Publishing.

- ↑ Cruikshank, 2001, Op. cit.-Gubser, N.J., 1965.The Nunamiut Eskimo: Hunters of Caribou.Yale University Press;-Krupnik, I., 1993. Arctic Adaptations: Native Whalers and Reindeer Herders of Northern Eurasia. University Press of New England, xvii + 355p.;-Minc, L.D., 1986. Scarcity and survival: the role of oral tradition in mediating subsistence crises. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 5:39–113.