Incorporating traditional knowledge in the Arctic

This is Section 10.2.7 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Author: Michael B. Usher; Contributing Authors:Terry V. Callaghan, Grant Gilchrist, Bill Heal, Glenn P. Juday, Harald Loeng, Magdalena A. K. Muir, Pål Prestrud

Other chapters within this assessment address the impacts of climate change on indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as on their traditional lifestyles, cultures, and economies. Other chapters also report on the value of traditional knowledge, and the observations of indigenous peoples and local communities in understanding past and future impacts of climate change. This section focuses on the relationship between biodiversity and climate change, impacts on indigenous peoples, and the incorporation of traditional knowledge.

There has been increasing interest in recent years in understanding traditional knowledge. Analyses often link traditional knowledge with what is held sacred by local peoples. Ramakrishnan et al.[1] explored these links with a large number of case studies, largely drawn from areas of India, but also including studies based in other parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and southern Europe. A focus on northern America, again with a number of case studies, was reported by Maynard[2]. The many case studies demonstrate that traditional knowledge is held by peoples worldwide, except perhaps in the most developed societies where the link between people and nature has largely been broken. A recognition of this breakdown is the first step toward restoring biodiversity and its conservation in a changing world using knowledge that has been built up over centuries or millennia. As Ramakrishnan et al.[3] reported "although the links between traditional ecological knowledge on the one hand, and biodiversity conservation and sustainable development on the other, are globally recognized, there is a paucity of models which demonstrate the specificity of such links within a given ecological, economic, socio-cultural and institutional context". They state that "we need to understand how traditional societies. . . have been able to cope up with uncertainties in the environment and the relevance of this about their future responses to global change". These concepts point the way to a greater integration of the knowledge of indigenous peoples into the present and future management of the Arctic’s biodiversity.

A recent report by the Secretariat for the Convention on Biodiversity on inter-linkages between biological diversity and climate change[4] specifically addresses projected impacts on indigenous and traditional peoples. The term "traditional peoples" is used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its report on climate change and biodiversity[5] to refer to local populations who practice traditional lifestyles that are often rural, and which may, or may not, be indigenous to the location. This definition thus includes indigenous peoples, as used in the present assessment. The SCBD[6] report began by noting that indigenous and traditional peoples depend directly on diverse resources from ecosystems for many goods and services. These ecosystems are already stressed by current human activities and are projected to be adversely affected by climate change[7]. In addition to incorporating the main findings of the IPCC report[8], the SCBD report concluded as follows:

- The effects of climate change on indigenous and local peoples are likely to be felt earlier than the general impacts. The livelihood of indigenous peoples will be adversely affected if climate and land use change lead to losses in biodiversity, especially mammals, birds, medicinal plants, and plants or animals with restricted distribution (but have importance in terms of food, fiber, or other uses for these peoples) and losses of terrestrial, coastal, and marine ecosystems that these peoples depend on.

- Climate change will affect traditional practices of indigenous peoples in the Arctic, particularly fisheries, hunting, and reindeer husbandry. The ongoing interest among indigenous groups relating to the collection of traditional knowledge and their observations of climate change and its impact on their communities could provide future adaptation options.

- Cultural and spiritual sites and practices could be affected by sea-level rise and climate change. Shifts in the timing and range of wildlife species due to climate change could impact the cultural and religious lives of some indigenous peoples. Sea-level rise and climate change, coupled with other environmental changes, will affect some, but not all, unique cultural and spiritual sites in coastal areas and thus the people that reside there.

- The projected climate change impacts on biodiversity, including disease vectors, at the ecosystem and species level could impact human health. Many indigenous and local peoples live in isolated rural living conditions and are more likely to be exposed to vector and water-borne diseases and climatic extremes and would therefore be adversely affected by climate change. The loss of staple food and medicinal species could have an indirect impact and can also mean potential loss of future discoveries of pharmaceutical products and sources of food, fiber, and medicinal plants for these peoples.

The SCBD report commented directly on the incorporation of traditional knowledge and biodiversity by noting that the collection of traditional knowledge, and the peoples’ observations of climate change and its impact on their communities, could provide future adaptation options. Traditional knowledge can thus be of help in understanding the effects of climate change on biodiversity and in managing biodiversity conservation in a changing environment, including (but not limited to) genetic diversity, migratory species, and protected areas. The report also noted the links between biodiversity conservation, climate change, and cultural and spiritual sites and practices of indigenous people, emphasizing that shifts in the timing and range of wildlife species could impact on the cultural and religious lives of some indigenous peoples. A detailed consideration of the links between cultural and spiritual sites and practices on the one hand and indigenous peoples on the other has been published recently[9]. Although this report focused on sacred sites of indigenous peoples in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the Koryak Autonomous Okrug in northern Russia, it also examined wider arctic and international aspects with some consideration given to the conservation value of sacred sites for indigenous peoples in Alaska and northern Canada.

Local people have knowledge about biodiversity, although it might neither be recognized as such nor formulated using the terminology of scientific biodiversity, that can be of great assistance in the management of arctic biodiversity. Muir[10] discussed the models and decision frameworks for indigenous participation in coastal zone management using Canadian experience, and pointed out that commercial harvesting of fish and marine mammals, as well as the effects of tourism, can conflict with local peoples’ subsistence harvesting rights for fish and marine mammals. Traditional knowledge is multi-faceted[11] and very often traditional methods of harvesting and managing wildlife have been sustainable[12]. It is these models of sustainability that need to be explored more fully as the biodiversity resource changes, and the potential for its sustainable harvesting changes with a changing climate.

Chapter 10: Principles of Conserving the Arctic’s Biodiversity

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Conservation of arctic ecosystems and species

10.2.1 Marine environments

10.2.2 Freshwater environments

10.2.3 Environments north of the treeline

10.2.4 Arctic boreal forest environments

10.2.5 Human-modified habitats

10.2.6 Conservation of arctic species

10.2.7 Incorporating traditional knowledge

10.2.8 Implications for biodiversity conservation

10.3 Human impacts on the biodiversity of the Arctic

10.4 Effects of climate change on the biodiversity of the Arctic

10.5 Managing biodiversity conservation in a changing environment

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Incorporating traditional knowledge in the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Incorporating_traditional_knowledge_in_the_Arctic- ↑ Ramakrishnan, P.S., K.G. Saxena and U.M. Chandrashekara (eds.), 1998. Conserving the Sacred for Biodiversity Management. Oxford and IBH Publishing.

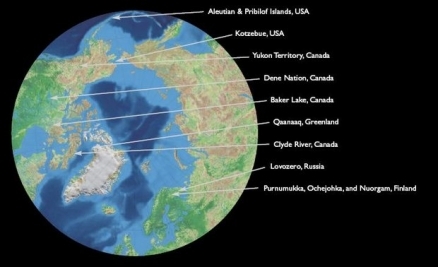

- ↑ Maynard, N.G. (ed.), 2002. Native Peoples – Native Homelands: Climate Change Workshop. Final Report: Circles of Wisdom. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Albuquerque.

- ↑ Ramakrishnan, P.S., U.M. Chandrashekara, C. Elouard, C.Z. Guilmoto, R.K. Maikhuri, K.S. Rao, S. Sankar and K.G. Saxena (eds.), 2000. Mountain Biodiversity, Land Use Dynamics, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Oxford and IBH Publishing.

- ↑ SCBD, 2003. Interlinkages between biological diversity and climate change. Advice on the integration of biodiversity considerations into the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity,Technical Series, 10.

- ↑ IPCC, 2002. Climate Change and Biodiversity. Gitay, H., A. Suarez, R.T. Watson and D.J. Dokken (eds.).World Meteorological Organization and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ↑ SCBD, 2003. Interlinkages between biological diversity and climate change. Advice on the integration of biodiversity considerations into the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity,Technical Series, 10.

- ↑ SCBD, 2003. Interlinkages between biological diversity and climate change. Advice on the integration of biodiversity considerations into the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity,Technical Series, 10.

- ↑ IPCC, 2002. Climate Change and Biodiversity. Gitay, H., A. Suarez, R.T. Watson and D.J. Dokken (eds.).World Meteorological Organization and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ↑ CAFF, 2002b.The conservation value of sacred sites of indigenous peoples of the Arctic: a case study in northern Russia – report on the state of sacred sites and sanctuaries. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna,Technical Report, 10.

- ↑ Muir, M.A.K., 2002b. Models and decision frameworks for indigenous participation in coastal zone management in Queensland, based on Canadian experience. Coat to Coast 2002, Australia's National Coastal Conference, pp.303–306.

- ↑ Burgess, P., 1999.Traditional Knowledge. Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat, Copenhagen.

- ↑ Jonsson, B., R. Andersen, L.P. Hansen, I.A. Fleming and A. Bjørge, 1993. Sustainable Use of Biodiversity. Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning,Trondheimones.