Climate change impacts on Indigenous caribou systems of North America

This is Section 12.3.5 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment Lead Author: Mark Nuttall; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Bruce Forbes, Gary Kofinas,Tatiana Vlassova, George Wenzel

Subsistence caribou hunting in North America is practiced by Dogrib, Koyukon, Gwich’in, Dene, Cree, Chipewyan, Innu, Naskapi, Yupiit, Iñupiat, Inuvialuit, Inuit, and other indigenous peoples from the Ungava Peninsula of Labrador (Canada) to the western Arctic of Alaska (Fig. 12.2). While the cultural role of caribou differs among these groups, caribou is arguably the most important terrestrial subsistence resource for indigenous hunters in arctic North America[1]. The total annual harvest by North American hunters is estimated to be more than 160,000 animals, with its replacement value as store-bought meat roughly equivalent to US$30,000,000.

Fig. 12.2. North American distribution of Rangifer subspecies and selected indigenous peoples of North America[2].

Fig. 12.2. North American distribution of Rangifer subspecies and selected indigenous peoples of North America[2]. While this monetary value illustrates the enormous contribution caribou make to the northern economy, it does not capture the social, psychological, and spiritual value of caribou to its users. For many indigenous culture groups who identify themselves as "caribou people", like the Gwich’in, Naskapi, and Nunamiut, caribou–human relations represent a bond that blurs the distinction between people, land, and resources, and links First Peoples of the North with their history. This intimate relationship between people and caribou suggests that negative impacts from climate change on caribou and caribou hunting would have significant implications for the well-being of many indigenous communities, their sense of security and tradition, and their ability to meet their basic nutritional needs.

The caribou production system of the Vuntut Gwitchin, people whose traditional territories and settlement are centered on Old Crow, Yukon, may be used to illustrate variables that must be considered in climate change assessments of northern caribou user communities.

Contents

- 1 The enduring relationship of people and caribou (12.3.5.1)

- 2 Modern-day subsistence systems (12.3.5.2)

- 3 Conditions affecting caribou availability (12.3.5.3)

- 4 Keeping climate assessment models in perspective (12.3.5.4)

- 5 Conclusions (12.3.5.5) Local community hunters of Old Crow and many others across North America have noted an overall increase in the variability of weather conditionsendnote_29. These observations are coupled with an awareness of social and cultural changes in communities. While it will be difficult to make predictions about the trajectories of future climate conditions and their anticipated impacts on caribou and caribou subsistence systems, it is clear that the associated variability and overall uncertainty pose special problems for caribou people like the Vuntut Gwitchin of Old Crow. Indeed, local observations of later autumn freeze-up of rivers (Climate change impacts on Indigenous caribou systems of North America) , drying of lakes and lowering of water levels in rivers, an increase in willow and birch in some areas, shifts in migrations and distribution patterns, and restrictions on access suggest that the problems of climate change are already being experienced. While the challenges of climate change and climate change assessments for local hunters and researchers are considerable, there are clear opportunities for collaboration between groups to ensure the sustainability of the subsistence way of life.

- 6 References

- 7 Citation

The enduring relationship of people and caribou (12.3.5.1)

Caribou have been of critical importance to northern peoples of North America for millennia[3]. Archaeological evidence suggests that during the Wisconsin Glaciation, the distribution of Rangifer extended across much of the western hemisphere[4], from as far south as New Jersey to New Mexico and Nevada[5]. Caribou were available to paleo-indigenous hunters seasonally, with variation in availability related to a herd’s ecological rhythms, human territoriality and mobility, and access to other living resources. Shifts in climate regimes that precipitated glacial epochs had dramatic consequences for caribou and the peoples that depended upon them. Recent evidence from the southern Yukon shows how shifts in climate have resulted in dramatic changes in the distribution of caribou, while remaining a part of the oral traditions and identity of indigenous peoples well after the disappearance of large herds[6].

The traditional caribou hunting grounds of the Vuntut Gwitchin are located within the caribou range of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, a region referred to as the Yukon–Alaska Refugium (see Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA), Chapter 11), and considered to have been unglaciated throughout the four glacial epochs. Paleontological evidence suggests that caribou have continually inhabited the Alaska–Yukon Refugium for over 400,000 years, through the Wisconsin Glaciation. Archaeological evidence of human habitation in this region is among the oldest excavated in North America. While questionable artifacts have been used to suggest the presence of humans in the area 25,000 to 29,000 years ago, confirmed findings at the Bluefish Caves, located on the Bluefish River southeast of Old Crow, Yukon have been dated 17,000 to 12,000 years old, including the bones of caribou.

Archaeological research linking proto Gwich’in to the present-day hunters identifies a complex of sites on the Porcupine and Crow Rivers, and indicates continual human inhabitation of the region and use of Porcupine Caribou for around 2,000 years. Many of the sites are situated at present-day caribou river crossings, with material culture and subsistence patterns closely related to the caribou resource. Other noteworthy sites include more than 40 caribou fences, strategically located across the southern range of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, and used by the Gwich’in families until the beginning of the 19th century[7].

Social organization of caribou production traditionally reflects the seasonal cycle of caribou movements, overall changes in herd population, and access to other important subsistence resources. In winter, when caribou herds are mostly sedentary, traditional hunting involved small-group hunts and stalking; autumn migration brought large numbers of caribou and was undertaken by larger parties and family groups, intercepting caribou at traditional river crossings and/or directing movements of wild caribou into corrals. High demand for caribou meat in preparation for winter required large-scale harvests involving considerable effort by family groups. Limited summer hunts of young caribou provided lighter hides that were important for clothing. While traditional caribou hunting is often described as cooperative in behavior and egalitarian in social structure, recognition of exceptional hunting abilities was critical to survival. Caribou fences of the Vuntut Gwitchin are reported to have been "owned" by skilled hunting leaders, with a fence complex capable of harvesting as many as 150 animals in a single round-up, and managed by as many as 12 families. Cooperation among groups situated at different fences was necessary for managing the annual variability in migration patterns and uneven hunting success of family groups.

Ethnological studies of Porcupine Caribou users document the central role of caribou in community life[8]. Oral histories are replete with accounts of human migration, exceptional hardship, and starvation, due to the unavailability of caribou. While some have argued that over-hunting has been a key factor driving the declines observed in many northern wildlife populations[9], there is little evidence that over-hunting of caribou by indigenous peoples was the sole cause of population decline in large herds. Given the population estimates of indigenous hunters in the pre-contact period, it is more likely that changes in caribou populations of large herds and shifts in their distributions were driven primarily by climate[10], with hunting contributing to these changes at low population levels.

Modern-day subsistence systems (12.3.5.2)

Caribou is still a vibrant component of many caribou user communities’ dual cash–subsistence economies. For example, harvest data for the community of Old Crow (population ~275) show that the annual per capita caribou harvest has been as high as five animals[11]. Modern-day harvesting in the community of Old Crow generally occurs during autumn, winter, and spring, with the autumn harvest the most important. In autumn, bull caribou are in prime condition (i.e., fat) and the cooler temperatures allow open-air production of drying meat, with use of boats to hunt at crossings. Winter harvesting does occur, but is generally limited because the herd’s winter distribution is too far from the community to allow affordable access. The spring hunt by the Vuntut Gwitchin provides a supply of fresh meat after the long winter, but is limited by the warmer temperatures which constrain caribou production and storage of meat in caches. Governing the activities of harvesters is a strong local ethic against waste.

The location of modern-day settlements has consequences for the success of community caribou hunting. Communities, like Old Crow, sited at the center of the range of large migratory herds are able to intercept caribou during autumn and spring migrations, whereas communities sited on the margin of a herd’s range may have access to animals only during winter or briefly during the summer calving and post-calving periods. History shows that the range of a large herd can contract at low population levels and expand at high levels. The consequence for local communities situated away from the heart of a herd’s range can be a decline in hunting success and in some cases abandonment of caribou hunting for several decades until the herd returns to a higher population level.

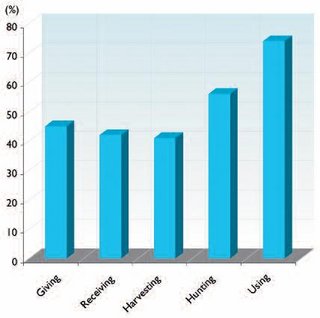

An important mechanism for adaptation and survival of traditional indigenous subsistence economies is a system of reciprocity through the sharing of harvested animals. Data from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game show the extent to which household sharing occurs in fifteen Western Arctic Herd user communities (Fig. 12.3). Networks of exchange are internal to communities and usually kinship-based. These networks also extend to residents of neighboring communities and regional centers[12]. Central to this exchange process and in hunting success for many traditional hunters is the concept of luck. Like many hunting peoples, luck in hunting is regarded by many Vuntut Gwitchin not just as a matter of hit-or-miss probability, but also as the consequence of human deference and respect for animals, and generosity in sharing harvests with fellow community members[13].

Caribou subsistence hunting in indigenous communities of the north is today practiced as part of a dual cash–subsistence economy[14]. Cash inputs (e.g., jobs, transfer payments, investments by Native Corporations) supply essential resources for the acquisition of modern-day hunting tools. The transition to improved hunting technologies (e.g., bigger and faster snowmobiles and boats, outboard motors with greater horsepower, high-powered rifles, and access to caribou radio-collar distribution and movement data via the internet), allows greater access to caribou than in previous years, and a more consistent availability of fresh meat, which thus changes the level and type of uncertainty that has traditionally been associated with indigenous caribou hunting.

Government policies and agreements dictate if and how caribou harvesting enters into the realm of monetary exchange. For example, the State of Alaska and the U.S.-Canada International Agreement for the Conservation of the Porcupine Caribou Herd (1987) prohibits the commercial harvest and sale of caribou, whereas commercial tags for caribou of other herds are permitted for herds of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Quebec, where several for-profit native and non-native corporations participate. Outfitter caribou hunting is also practiced as a component of local mixed economies in some regions. In some indigenous communities, there is a resistance to engage in guided caribou hunting, a policy that is defended as a need to retain traditional values and avoid commercialization of a sacred resource.

Many have speculated that engagement of subsistence hunters with the cash economy and the effects of modernization would ultimately lead to a decrease in participation in the subsistence way of life[15]. Yet, evidence demonstrates that under some conditions subsistence hunting can thrive in a modern context[16]. The changes have, however, affected the allocation of time resources, including the time community members spend on the land pursuing a subsistence way of life[17]. Whereas before 1960 there was great flexibility in the allocation of time for subsistence harvesting and trapping, today’s pursuit of employment and educational opportunities and its attendant shift to "clock time" is noted by many people at the local level as constraining opportunities for harvesting and affecting the transmission of cultural hunting traditions to younger generations. Relevant in the discussion about climate change and subsistence caribou hunting is the process by which financial resources compensate for the more constrained schedules of today’s hunters, by improving technologies for time-efficient travel to hunting grounds[18]. The shift to improved harvesting technologies also suggests that climate change impacts on community caribou hunting be considered within the context of a cultural system that is highly dynamic and with some (but not infinite) capacity for adaptation.

Critically relevant to a community’s adaptive capacity is its collective knowledge of caribou and caribou hunting[19], which includes an understanding of the distribution and movement of animals in response to different weather conditions[20]. Community ecological knowledge of caribou is local in scale, and provides an important basis for hunters’ decisions about the allocation of hunting resources (time, gas, and wear and tear on snow machines and boats) and the quantity of caribou to be harvested. This knowledge is sustained through the practice of caribou hunting traditions (i.e., time spent hunting and being on the land), and the transmission of knowledge and its cultural traditions to younger generations.

Conditions affecting caribou availability (12.3.5.3)

Maintaining conditions for successful caribou hunting is not just a question of sustaining caribou herds at healthy population levels, but includes consideration of a complex and interacting set of social, cultural, political, and ecological factors. While environmental conditions (e.g., autumn storms, snow depth, rate of spring snow melt) may affect the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s seasonal and annual distribution and movements[21], associated factors (e.g., timing of freeze-up and break-up, shallow snow cover, and the presence of "candle ice" on lakes) may affect hunters’ access to hunting grounds. Individual and community economic conditions affecting hunters’ access to equipment and free time for hunting are also key elements. Consequently, assessing caribou availability in conditions of climate change requires an approach that is more multifaceted than standard subsistence use documentation or "traditional ecological knowledge" documentation. Table 1 lists some of the key variables important in climate change assessments for caribou subsistence systems.

|

Table 1. Key variables and their implications for assessments of climate change effects on caribou availability[22]. | |

|

Caribou population level |

A decrease in total stock of animals has implications for the total range occupied by the herd; the likelihood hunters will see caribou while hunting, and management policy affecting the allocation and possible restrictions of harvests. |

|

Distribution and movement of herd |

Climate conditions are critical in the caribous’ selection of autumn and spring migratory patterns and winter grounds. Calving locations affect community hunters’ proximity to caribou. |

|

Time for hunting; time on the land |

Time for hunting emerges as an important variable as more community members engage in full-time participation in the wage economy. It is also important functionally in the maintenance and transmission of knowledge of caribou hunting. |

|

Community demographics |

Community demographics determine present and future demand for caribou. Out migration of people to distant cities may also affect the knowledge base if residence outside the community is for an extended period. |

|

Household structure |

Household structure affects resources (people and gear) that can be pooled for hunting. For example, households comprising adult bachelors often serve as important providers for households with non-hunters (e.g., elders, women, full-time working members who have limited time or no skill). |

|

Cash income |

Cash income provides for acquisition of gear needed in harvesting and compensation when time restrictions limit hunting opportunities. Where barter and trade allow for monetary exchange, it permits direct acquisition of meat. |

|

Technology for harvesting caribou |

Faster boats and snow machines, improved GPS systems, and lighter outdoor gear can bring hunting areas previously inaccessible due to high travel costs, within reach. Increased use of high technology gear can increase the demand for cash to support subsistence harvesting. |

|

Cultural value |

Cultural value affects interest in caribou hunting rates of consumption, and ethics of hunting practice. |

|

Sharing |

Inter- and intra-community sharing buffers against household caribou shortfall. Some indigenous peoples believe that sharing also ensures future hunting success. |

|

Social organization of the hunt |

Hunting as individuals or in "community hunts" are both successful strategies. |

|

Formal state institutions for management of caribou |

Formally recognized institutions, such as a rural or native hunting priority, may prove critical when a herd is determined by management boards to be at low levels (see ACIA, Chapter 11 for more details). |

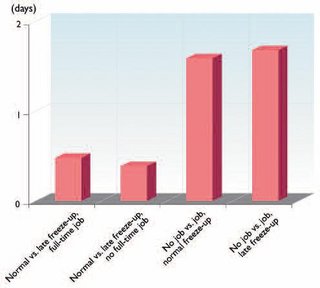

Fig. 12.4. Change in compensating variation from caribou hunting[23].

Fig. 12.4. Change in compensating variation from caribou hunting[23]. A simulation model based on Old Crow caribou hunting and the cash economy was constructed based on local knowledge and quantitative socio-economic data[24]. The model drew on local knowledge and science-based research to assess the implications of a climate change scenario that assumed later break-up of ice on the Porcupine River, an important water-course for intercepting caribou during the autumn migration. The model results revealed variation in compensatory levels for households with different types of employment. Figure 12.4 shows the estimated compensating variation for the possible changes in work and climate patterns based on 1993 hunting conditions for a household with three adults, two children, and no autumn harvest. The model suggests that late freeze-up costs the example household the equivalent of about half a day in lost leisure or family time. The loss for this scenario is modest because caribou were present near the community during early winter in 1993, which meant that the access restriction still left hunters with some harvest opportunities even though these were not plentiful for the season for which data were available, and relatively few households would have hunted even under normal climate conditions. The loss in leisure or family time is slightly less if no-one in the household has full-time work. The compensating variation for having a job is negative, and about three times as large as the cost of the late freeze-up. This suggests that having a full-time job under these conditions reduces the household’s welfare because it leaves insufficient time to hunt. If the data were for a year with more plentiful caribou, the cost would have been greater. The model does not include the increased risk of exposure for hunters attempting to intercept caribou during late freeze-up conditions, which typically include traveling up river by boat through moving ice[25].

Fig. 12.5. Projected number of years in each decade that households (HH) have caribou harvest shortfalls[26].

Fig. 12.5. Projected number of years in each decade that households (HH) have caribou harvest shortfalls[26]. The Sustainability of Arctic Communities Synthesis Model[27], based on the integrated assessment of 22 scientists and four indigenous Porcupine Caribou user communities, projected the effects of a 40-year climate change scenario. Scenario assumptions included warmer and longer summers and greater variability in snow conditions, including deeper snow in winter, shallower snow in winter, and fewer "average" snow years. The results show that the combined effects of these conditions result in a significant decrease in the herd’s population (see ACIA, Chapter 11 for details of the impacts on caribou populations). The model assumes that no harvest restriction is implemented, and that intra-community sharing of caribou and community hunts are organized in years when most of the community households do not meet their target needs. In this climate change scenario, the model projects that within seven years of the final decade, less than half the households will meet half their caribou needs (Fig. 12.5).

Keeping climate assessment models in perspective (12.3.5.4)

Community involvement in the Sustainability of Arctic Communities Synthesis Model project and documentation of local knowledge on climate change through the Arctic Borderlands Ecological Knowledge Cooperative[28] provide insights into the challenges associated with trying to assess the impacts of climate change on subsistence caribou hunting. Despite the effort of researchers to capture the key drivers and stochastic characteristics of the systems, a local review of the model pointed to problems because of the complexity of the system. For example, the Sustainability of Arctic Communities Synthesis Model assumes that warmer summer temperatures under climate change will result in an increase in insect harassment for caribou and an associated cost to the caribou energy budget. Caribou hunters of Aklavik, Northwest Territories, who have observed a recent increase in summer temperature, have also observed an increase in summer winds, and thus an overall decrease in insect harassment to caribou. Community members from Old Crow questioned the use of a climate change scenario that assumes a regional increase in snow depth, since the model does not include the mosaic of landscape variation in their region. While these interactions illustrate some of the limitations of models in the assessment of climate change effects on local community use of subsistence resources, they do highlight that the involvement of communities as full partners in an integrated assessment can be of value in identifying data gaps, directing the work of future research, and portraying assessment results in ways that reflect the uncertainty and complexity of changes in the relationships between people and their environment.

Conclusions (12.3.5.5) Local community hunters of Old Crow and many others across North America have noted an overall increase in the variability of weather conditionsendnote_29. These observations are coupled with an awareness of social and cultural changes in communities. While it will be difficult to make predictions about the trajectories of future climate conditions and their anticipated impacts on caribou and caribou subsistence systems, it is clear that the associated variability and overall uncertainty pose special problems for caribou people like the Vuntut Gwitchin of Old Crow. Indeed, local observations of later autumn freeze-up of rivers (Climate change impacts on Indigenous caribou systems of North America) , drying of lakes and lowering of water levels in rivers, an increase in willow and birch in some areas, shifts in migrations and distribution patterns, and restrictions on access suggest that the problems of climate change are already being experienced. While the challenges of climate change and climate change assessments for local hunters and researchers are considerable, there are clear opportunities for collaboration between groups to ensure the sustainability of the subsistence way of life.

Chapter 12. Hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering: indigenous peoples and renewable resource use in the Arctic

12.1 Introduction (Climate change impacts on Indigenous caribou systems of North America)

12.2 Present uses of living marine and terrestrial resources

12.2.1 Indigenous peoples, animals, and climate in the Arctic

12.2.2 Mixed economies

12.2.3 Renewable resource use, resource development, and global processes

12.2.4 Renewable resource use and climate change

12.2.5 Responding to climate change

12.3 Understanding climate change impacts through case studies

12.3.1 Canadian Western Arctic: the Inuvialuit of Sachs Harbour

12.3.2 Canadian Inuit in Nunavut

12.3.3 The Yamal Nenets of northwest Siberia

12.3.4 Indigenous peoples of the Russian North

12.3.5 Indigenous caribou systems of North America

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Climate change impacts on Indigenous caribou systems of North America. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Climate_change_impacts_on_Indigenous_caribou_systems_of_North_America- ↑ Hudson, R.J., K.R. Drew and L.M. Baskin (eds.), 1989. Subsistence Hunting. Wildlife Production Systems: Economic Utilisation of Wild Ungulates. Cambridge University Press.–Klein, D., 1989. Subsistence hunting. In: R.J. Hudson, K.R. Drew and L.M. Baskin (eds.). Wildlife Production Systems: Economic Utilisation of Wild Ungulates, pp. 96–111. Cambridge University Press.–Kofinas, G., G. Osherenko, D. Klein and B. Forbes, 2000. Research planning in the face of change: the human role in reindeer/caribou systems. Polar Research, 19(1):3–22.

- ↑ Kofinas, G. and D. Russell, 2004. North America. In: family-based Reindeer Herding and Hunting Economies and the Status and Management of Wild Reindeer/Caribou Populations. Centre for Saami Studies, University of Tromsø.

- ↑ Burch, E.S. Jr., 1972. The caribou/wild reindeer as a human resource. American Antiquity, 37(3):337–368.–Lynch, T.F., 1997. Introduction. In: L.J. Jackson and P. T. Thacker (eds.). Caribou and Reindeer Hunters of the Northern Hemisphere. Ashgate Publishing.–Hall, E., (ed.), 1989. People and Caribou in the Northwestern Territories. Department of Renewable Resources, Government of Northwest Territories, Yellowknife.

- ↑ Banfield,A. W.F., 1961. Revision of the Reindeer and Caribou, genus Rangifer. National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 177, vi+137pp. Banfield,A. W.F., 1974. The Mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press. xxv + 438pp.–Kelsall, J.P., 1968. The Migratory Barren-Ground Caribou of Canada. Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa.–Spiess, A.E., 1979. The Reindeer and Caribou Hunters: An Archeological Study. Academic Press, 312pp.

- ↑ Jackson, L.J. and P. T. Thacker (eds.), 1997. Caribou and Reindeer Hunters of the Northern Hemisphere. Ashgate Publishing, 272pp.–Lynch, T.F., 1997. Introduction. In: L.J. Jackson and P. T. Thacker (eds.). Caribou and Reindeer Hunters of the Northern Hemisphere. Ashgate Publishing.

- ↑ Farnell, R., P.G. Hare, E. Blake,V. Bowyer, C. Schweger, S. Greer and R. Gotthardt, 2004. Multidisciplinary investigations of alpine ice patches in southwest Yukon, Canada: paleoenvironmental and paleobiological investigations. Arctic, 57(3):247–259.–Hare et al., in press. Multidisciplinary investigations of Alpine ice patches in southwest Yukon, Canada: ethnographic and archaeological Investigations. Arctic Ms#03–151.

- ↑ Greer, S.C. and R.J. Le Blanc, 1992. Background Heritage Studies – Proposed Vuntut National Park. Northern Parks Establishment Office, Canadian Parks Service, 116pp.–McFee, R.D. (no date). Caribou fence facilities of the historic Yukon Kutchin. In: Megaliths to Medicine Wheels: Boulder Structures in Archaeology, pp. 159–170. Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Chacmool Conference, University of Toronto.–Warbelow, C., D. Roseneau and P. Stern, 1975. The Kutchin Caribou Fences of Northeastern Alaska and the Northern Yukon. Studies of Large Mammals along the Proposed Mackenzie Valley Gas Pipeline Route from Alaska to British Columbia. Biological Report Series. Volume 32. J.R.D., Renewable Resources Consulting Services Ltd, 129pp.

- ↑ Balikci, A., 1963. Family organization of the Vunta Kutchin. Arctic Anthropology, 1(2):62–69.–Slobodin, R., 1962. Band Organization of the Peel River Kutchin. National Museum of Canada.–Slobodin, R., 1981. Kutchin. In: J. Helm (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 6: Subarctic, pp. 514–532. Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

- ↑ Martin, C., 1978. Keepers of the Game. University of California Press.

- ↑ Peterson, D.L. and D.R. Johnson (eds.), 1995. Human Ecology and Climate Change: People and Resources in the Far North. Taylor and Francis.

- ↑ Kofinas, G.P., 1998. The Cost of Power Sharing: Community Involvement in Canadian Porcupine Caribou Co-management. Ph.D. Thesis. University of British Columbia, 471pp.

- ↑ Magdanz, J.S., C.J. Utermohle and R.J. Wolfe, 2002. The production and distribution of wild food in Wales and Deering, Alaska. Division of Subsistence, Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Technical Paper 259.

- ↑ Feit, H., 1986. Hunting and the quest for power:The James Bay Cree and white men in the twentieth century. In: R.B. Morrison and C.R. Wilson (eds.). Native Peoples:The Canadian Experience, pp. 171–207. McClelland and Stewart.

- ↑ Langdon, S.J., 1986. Contradictions in Alaskan Native economy and society. In: S. Langdon (ed.). Contemporary Alaskan Native Economics, pp. 29–46. University Press of America.

- ↑ Murphy, S.C., 1986. Valuing Traditional Activities in the Northern Native Economy: the Case of Old Crow, Yukon Territory. M. A. Thesis, University of British Columbia, 189pp.

- ↑ Kruse, J. A., 1992. Alaska North Slope Inupiat Eskimo and resource development: why the apparent success? Prepared for presentation to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Annual Meeting, January 1992, Chicago.–Langdon, S.J., 1986. Contradictions in Alaskan Native economy and society. In: S. Langdon (ed.). Contemporary Alaskan Native Economics, pp. 29–46. University Press of America.–Langdon, S.J., 1991. The integration of cash and subsistence in Southwest Alaskan Yup'ik Eskimo communities. In:T. Matsuyama and N. Peterson (eds.). Cash, Commoditisation and Changing Foragers, pp. 269–291. Senri Publication No. 30. Osaka, Japan, National Museum of Ethnology.

- ↑ Kruse, J., 1991. Alaska Inupiat subsistence and wage employment patterns: understanding individual choice. Human Organization, 50(4):317–326.

- ↑ Berman, M. and G. Kofinas, 2004. Hunting for models: rational choice and grounded approaches to analyzing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecological Economics, 49(1):31–46.

- ↑ Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred Ecology:Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor and Francis, 209pp.

- ↑ Kofinas, G., Aklavik, Arctic Village, Old Crow and Fort McPherson, 2002. Community contributions to ecological monitoring: knowledge co-production in the U.S.-Canada Arctic borderlands. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 54–91. Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Eastland, W.G., 1991. Influence of Weather on Movements and Migration of Caribou. M.S. Thesis. University of Alaska Fairbanks, 111pp.–Fancy, S.G., L.F. Pank, K.R. Whitten and L. W. Regelin, 1986. Seasonal movement of caribou in Arctic Alaska as determined by satellite. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 67:644–650.–Russell, D.E., K.R. Whitten, R. Farnell and D. van de Wetering, 1992. Movements and Distribution of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, 1970–1990. Tech. Rep. 139. Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region.–Russell, D.E.,A.M. Martell and W. A.C. Nixon, 1993. The range ecology of the Porcupine Caribou Herd in Canada. Rangifer Special Issue, 8: 168. Sabo III G., 1991. Long Term Adaptations among Arctic Hunter Gatherers. Garland Publishing.

- ↑ Berman, M. and G. Kofinas, 2004. Hunting for models: rational choice and grounded approaches to analyzing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecological Economics, 49(1):31–46.–Kruse, J. A., R.G. White, H.E. Epstein, B. Archie, M.D. Berman, S.R. Braund, F.S. Chapin III, J. Charlie Sr., C.J. Daniel, J. Eamer, N. Flanders, B. Griffith, S. Haley, L. Huskey, B. Joseph, D.R. Klein, G.P. Kofinas, S.M. Martin, S.M. Murphy, W. Nebesky, C. Nicolson, K. Peter, D.E. Russell, J. Tetlichi, A. Tussing, M.D. Walker and O.R. Young, 2004. Sustainability of Arctic communities: an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers and local knowledge holders. Ecosystems, 7:1–14.

- ↑ Berman, M. and G. Kofinas, 2004. Hunting for models: rational choice and grounded approaches to analyzing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecological Economics, 49(1):31–46.

- ↑ Berman, M. and G. Kofinas, 2004. Hunting for models: rational choice and grounded approaches to analyzing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecological Economics, 49(1):31–46.

- ↑ Berman, M. and G. Kofinas, 2004. Hunting for models: rational choice and grounded approaches to analyzing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecological Economics, 49(1):31–46.

- ↑ Kruse, J. A., R.G. White, H.E. Epstein, B. Archie, M.D. Berman, S.R. Braund, F.S. Chapin III, J. Charlie Sr., C.J. Daniel, J. Eamer, N. Flanders, B. Griffith, S. Haley, L. Huskey, B. Joseph, D.R. Klein, G.P. Kofinas, S.M. Martin, S.M. Murphy, W. Nebesky, C. Nicolson, K. Peter, D.E. Russell, J. Tetlichi, A. Tussing, M.D. Walker and O.R. Young, 2004. Sustainability of Arctic communities: an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers and local knowledge holders. Ecosystems, 7:1–14.

- ↑ Kruse, J. A., R.G. White, H.E. Epstein, B. Archie, M.D. Berman, S.R. Braund, F.S. Chapin III, J. Charlie Sr., C.J. Daniel, J. Eamer, N. Flanders, B. Griffith, S. Haley, L. Huskey, B. Joseph, D.R. Klein, G.P. Kofinas, S.M. Martin, S.M. Murphy, W. Nebesky, C. Nicolson, K. Peter, D.E. Russell, J. Tetlichi, A. Tussing, M.D. Walker and O.R. Young, 2004. Sustainability of Arctic communities: an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers and local knowledge holders. Ecosystems, 7:1–14.

- ↑ Kofinas, G., 2002. Community contributions to ecological monitoring: knowledge co-production in the US-Canada Arctic borderlands. In: I. Krupnik, D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 54–91. Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, Fairbanks, Alaska.