Ilulissat Icefjord, Denmark-Greenland

Contents

- 1 Geographical Location

- 2 Dates and History of Establishment

- 3 Area

- 4 Land Tenure

- 5 Altitude

- 6 Physical Features

- 7 Climate

- 8 Vegetation

- 9 Fauna

- 10 Cultural Heritage

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 IUCN Management Category

- 17 Further Reading

Geographical Location

Ilulissat Icefjord (68°48'N to 69°31'N and 48°28' 51°16'W.) is located within the Arctic Circle on the west coast of Greenland in the bay of Disko Bugt approximately 1,000 kilometers (km) up the west coast of Greenland.

Dates and History of Establishment

The area is protected and conserved by an established framework of government legislation and protective designations and by local planning policies.

- 1980: The Nature Conservation Act for Greenland enacted. This act is the foundation framework for the protection of species, ecosystems and protected areas; a new act is being prepared;

- 2002: Management Plan for the site adopted by the Ilulissat Municipal Council;

- 2003: The Greenland Home Rule Executive Order No.5 passed for the Protection of Archaeological Sites and Buildings within the area; this order prohibits mining within the Protected Area.

Area

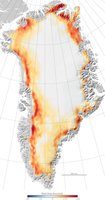

Image showing the melting of the Greenland ice cap. (Source: Earth Observatory NASA)

Image showing the melting of the Greenland ice cap. (Source: Earth Observatory NASA) Approximately 4,024 square kilometers (km2)., comprising 3,199 km2 of glacier ice, 397 km2 land, 386 km2 fjord and 42 km2 of lakes.

Land Tenure

Public. Administered by the Municipality of Ilulissat, Greenland.

Altitude

Sea level to the 1,200 meters (m) contour of the ice sheet.

Physical Features

The Ilulissat Icefjord is a tidewater ice-stream located 1,000 km up the west coast of Greenland. It drains into the bay of Disko Bugt (bight) which is partially blocked by the large island of Disko. The Icefjord (locally called Kangia) is the sea mouth of Sermeq Kujalleq, one of the few [[glacier]s] through which the ice of the Greenland ice cap reaches the sea. It is the second fastest and most prolific ice-calving tidewater glacier in Greenland producing a constant procession of icebergs and still actively eroding the fjord bed. The surroundings are low heavily glaciated PreCambrian gneiss and amphibolite rocks extending some 50 km inland to the ice cap with flanking lateral moraines and ice-dammed lakes; also lakelets, glacial striations, roches moutonées, and perched erratics typical of glaciated landscapes.

The Greenland ice cap, 1.7 million km2 in area, is the only remnant in the Northern Hemisphere of the continental ice sheets of the last Quaternary Ice Age. The icecap formed during the Middle and Late Pleistocene over a once temperate landscape, the south central part of which drained through large rivers to Disko Bugt, still marked as channels under the ice and submarine troughs. The ice cap's oldest ice is estimated to be 250,000 years old, maintained by the annual accumulation of snow matched by loss through calving and melting at the margins. The icecap holds a detailed record of past climatic change and atmospheric conditions (in trapped air bubbles) for this entire length of time, and shows that during the last ice age the climate fluctuated between extreme cold and warmer periods. This ended around 11,550 years ago, since when the climate has been more stable. Around Ilulissat Icefjord, the evidence of glaciation is mainly of the last 100,000 years. This culminated in the 'Little Ice Age' 500-100 years ago when the ice expanded in pulses to a maximum during the 19th century. A glacial recession has occurred during the 20th century. In 1851 the ice front across the fjord was 25 km east of the sea. By 1950 it had retreated some 26 km further east.

Sermeq Kujalleq is a river of crevassed ice with a catchment area of about 6.5% of the Greenland ice cap (~110,000 km). The ice stream is a narrow well-defined channel approximately 3-6 km wide. It stretches from the nose of the glacier to the 1,200 m contour (about 80-85 km inland) which is just below the point where ice accumulation is balanced by ablation. Near the ice sheet, it has a hummocky smooth surface with relatively few crevasses. The extensive summer melt is drained by large meltwater rivers often running in deep canyons and disappearing through moulins (glacial holes) into a sub-glacial drainage system sometimes termed ice karst. 50 km from the glacier front the ice becomes increasingly rugged; lakes and water-filled crevasses disappear. Marginal crevasses extend 5 km or more to each side of the ice stream. About 45 km inland from the front, the surface funnels towards the main outlet. About 10 km behind the front, a tributary ice stream joins. At the junction that is created at this point an ice rumple above the center of a sub-glacial sill restricts the main stream to a width of only 4 km. At the grounding line the glacier is consistently moving at the unusually fast rate of 19 m a day or about 7 km per year.

In ice sheets, movement can locally increase to several kilometers a year due to factors such as the subsurface topography, the nature of the outlet, the ice margin in deep trenches, diminished basal friction or increased basal sliding. Movement may be some hundreds of meters per year if there is little bottom stress. Sermeq Kujalleq flows in a deep trough of eroded rock that varies from about 1.9 km deep near the glacier grounding zone, with an ice surface of some 400 m above sea level (a.s.l.) to over 2.5 km deep 40 km behind the grounding zone where the ice surface is about 1,000 m a.s.l. The height above sea level of the 7.5 km-long calving front is 40-90 m along the north-south flank and 20 m along the east-west flank. The average height of the calving front is 80 m and the ice is estimated to be approximately 700 m thick. The outermost 10 km of the glacier is mostly a floating mass of ice except at an ice rumple on the southern edge over a sub-glacial sill. The floating part of the glacier moves up and down with the tide, with a maximum range of 3m, decreasing towards the grounding zone. This tidal variation results in a diurnal fluctuation of the grounding line, and ice-quake activity, varying in intensity with the tidal cycle, can be felt up-glacier about 8 km from the grounding zone. The fjord is frozen solid in winter and covered with floating brash and massive ice in summer.

Large-scale calving of the Greenland ice-cap occurs at only a few points along the circa 6,000 km-long [[coast]line], mainly on the west coast. The annual calving through Ilulissat Icefjord of over 40 cubic kilometers (km3) of ice is 10% of the production of the Greenland ice cap and more than any other glacier outside Antarctica.

It is caused by the expansion of bottom crevasses and tidal flexure along grounding lines, supported by water pressure in the crevasses. In summer, a thin surface layer is formed in Disko Bugt by melting glacier ice. Due to the vertical stratification of salinity the sun's heat is stored in this layer, resulting in high summer surface temperatures. The tides also cause de-coupling of the glacier from the cliffs on the fjord sides. Stresses in the ice plate set up by the bending of floating ice on its way out cause parts of the front to detach. In major events large tabular icebergs of up to 0.4 km3 break off. Calving is continuous and one estimate of the calving rate is around 35 km3 a year. In July 1985 during a pulse of tabular iceberg detachment, the calving front retreated almost 2 km in only 45 minutes but such a high rate of glacier movement occurs rarely, and it is only in summer that such large ice discharges occur. Generally bergs take 12 to 15 months to push through the ice-brash cover of the fjord and if sufficiently deep, accumulate over a sill in the bedrock at the fjord mouth until pushed or floated off. They are extremely variable in size and shape from small pieces to mountains of ice more than 100 m above sea level, often with pointed peaks. The whitish ice is often cut by bands of transparent bluish ice formed by the freezing of melt water in the marginal crevasses. Once at sea, the icebergs travel both south and north of Disko Island before entering Davis Strait between Greenland and Canada where they are first carried north by the West Greenland Current, then towards Canada, and then southwards with the Baffin and Labrador Currents, many not melting before they reach latitude 40°N.

In Sermeq Kujalleq (previously named Jakobshavn Isbræ) the relatively high speed of the ice flow results from the funnelling of ice from a large drainage basin into a narrow stream. The large calf production and high velocities imply a relatively fast response to climatic change, but the causes are still debated. The 'Jakobshavn effect' has been suggested to explain the high discharge rates and the stability of the ice sheet next to the glacier. It is primarily a relationship between crevasse creation due to increased melting and high exterior stress in a heavily fissured ice stream. Surface melting is greatly enhanced by surface crevassing, increasing the surface area many-fold. When surface meltwater refreezes internally, it releases huge amounts of latent heat thus softening the ice column. Meltwater, which reaches the bottom, increases the basal sliding rate by lubricating the ice-rock interface. This and other processes in the glacier increase the flow. The increased movement of Sermeq Kujalleq started around 1850 when higher temperatures after the end of the Little Ice Age increased surface melting on the lowermost parts of the ice sheet. The meltwater drained into cracks and moulins, warmed the ice internally and lubricated the bed, which started the surge-like movements that continue today, transforming the ice surface into the jumble of crevasses and seracs which characterize surging glaciers. There are other explanations, but it is assumed that the Jakobshavn effect could explain the present relatively high speed of the disintegration of the surviving ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica.

Climate

Ilulissat Icefjord is located above the Arctic Circle, and has sunless winters and nightless summers only two to three months long. The July mean temperature is 7.5°C, and maximum 10.3°C; the March mean is -19.9°C. Rainfall averages only 266 millimeters (mm), mostly in August and September. A persistent high pressure (Atmospheric pressure) system exists over the ]]Greenland ice cap\; conditions are often calm though there are occasional fierce storms and short-lived dry fohn winds off the ice cap which can raise temperatures by 10°C in a few hours.

Vegetation

Lapland Rose, endangered perennial shrub. (Source: UW Madison Department of Botany)

Lapland Rose, endangered perennial shrub. (Source: UW Madison Department of Botany) The flora of the area is a low-arctic type, typical of the nutrient-poor silicaceous soil which, where humid, shows solifluction effects such as frost boils. Colonization of the margins of retreating ice also provides examples of plant succession. The main plant communities of the area are heath, fell-field, snow-patch, herb-slope, willow-scrub, fen, river-bank, seashore and aquatic.

Heath dominated by dwarf-shrubs is the most widespread plant community. Typical species are dwarf birch Betula nana, Arctic crowberry Empetrum nigrum ssp.hermaphroditum and Arctic blueberry Vaccinium uliginosum ssp.microphyllum. Conspicuous are the aromatic narrow-leaved white-flowered Labrador-tea Ledum palustre ssp.decumbens and, on richer drier soils, the purple-flowered Lapland rose-bay Rhododendron lapponicum.

Fell-fields are found on dry wind-swept areas with open soil between tussocks. Several colorful species thrive here owing to low competition: white-flowered snow whitlowgrass Draba nivalis, diapensia Diapensia lapponica, yellow-flowered Arctic poppy Papaver radicatum, snow cinquefoil Potentilla nivea and the grass-like northern wood-rush Luzula confusa. In snow-patches the growing season is only four to six weeks long but matted cassiope Harrimanella hypnoides and dwarf willow Salix herbacea thrive. Late snow-patches with only some four weeks growing period have pigmy buttercup Ranunculus pygmaeus, dandelion Taraxacum sp.,mountain sorrel Oxyria digyna and island purslane Koenigia islandica.

The herb-slope is the lushest plant community, with species-rich vegetation. The slopes are usually south to southwest-facing under steep mountains where they receive meltwater all summer when the microclimate is mild. In winter, snow protects the slope. As many as 30 different species grow, among them Alpine bartsia Bartsia alpina, Alpine bistort Polygonum viviparum, Unalaska fleabane Erigeron humilis and thick-leaved whitlow grass Draba crassifolia.

Willow scrub can reach 1.5 m, though 1 m is more frequent. It shelters species such as interrupted clubmoss Lycopodium annotinum ssp. alpestre, common horsetail Equisetum arvense and in the drier parts round-leaved wintergreen Pyrola grandiflora. The more fertile [[fen]s] have a thick vegetation of grass-like plants, often dominated by Arctic water sedge Carex stans and mountain bog-sedge Carex rariflora. Arctic marsh willow Salix arctophila and flame-tipped lousewort Pedicularis flammea are frequent, Lapland buttercup Ranunculus lapponicus less frequent. Stony river shores are widespread, clothed only by pioneer species like willowherb Chamaenerion latifolium.

Characteristic sandy seashore plants are sea sandwort Honckenya peploides and lyme-grass Elymus mollis. On rocky and gravelly beaches there are gravel sedge Carex glareosa, sea plantain Plantago maritima, Greenland scurvygrass Cochlearia groenlandica and low stitchwort Stellaria humifusa. Salt marshes occur here and there in protected inlets, their lower parts dominated by creeping saltmarsh grass Puccinellia phryganodes, the upper parts by Pacific silverweed Potentilla egedii. Among aquatic plants, mare's-tail Hippuris vulgaris is frequent along the shores of many ponds, smaller lakes and slow flowing [[stream]s]. Quite common are northern bur-reed Sparganium hyperboreum, small pondweed Potamogeton pusillus ssp. groenlandicus, dwarf water-crowfoot Ranunculus confervoides and occasionally awlwort Subularia aquatica, which only blooms if the pond is totally desiccated (where the mudworm Limosella aquatica also thrives). Found here is the quite rare autumnal water starwort Callitriche hermaphroditica.

Approximately 160 species of phanerogams, three club-mosses Lycopodium annotinum, Diphasiastrum alpinum and Huperzia selago, two horsetails Equisetum arvense and E. variegatum, and four ferns Cystopteris fragilis, Dryopteris fragrans, Woodsia ilvensis and Woodsia glabella occur in the nominated area. Among the rarest species are Porsild's catspaw Antennaria porsildii, Greenland woodrush Luzula groenlandica and whitish bladderwort Utricularia ochroleuca.

Fauna

Reindeer typical of the Illulissat Icefjord. (Source: Marietta College)

Reindeer typical of the Illulissat Icefjord. (Source: Marietta College) The upwelling caused by calving icebergs brings up nutrient-rich water which supports prolific invertebrate life and attracts great numbers of fish, seals and whales that feed on the generated nutrients. Twenty species of fish have been recorded in the area, the dominant species is the flatfish Greenland halibut Reinhardtius hippoglossoides which feeds mainly on northern shrimp Pandalus borealis and euphausid crustaceans, also on capelin Mallotus villosus, polar cod Boreogadus saida and eelpouts Lycodes spp. The halibut migrates seasonally in and out of the fjord, living both on the benthos and in the open sea. Warmer waters bring the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua.and Ringed seal Phoca hispida and Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus to the area. The former two species live in the icefjord all year. All three species are hunted by man and feed on the halibut. Harp seals Phoca groenlandica, fin and minke whales Balaena physalis (VU) and B. acutorostrata occur in summer at the fjord mouth with very occasional blue and Greenland whales B. musculus (EN) and B. mysticetus. Beluga Delphinapterus leucas (VU) and narwal Monodon monoceros visit Disko Bugt in autumn and winter.

The sea birds are typical for the area, with numerous breeding colonies attracted by the high primary productivity of the glacier front, and by fish discarded by the local fishery. Large flocks of northern fulmar Fulmarus glacialis and gulls feed among the grounded icebergs. These are mainly Iceland gulls Larus glaucoides, glaucous gulls L. hyperboreus with lesser numbers of great black-backed gulls L. marinus, kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla and guillemots Cepphus grille with great cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo. Birds visiting the area include Brent goose Branta bernicla, common eider Somateria mollissima, red-breasted merganser Mergus serrator, pomarine skua Stercorarius pomarinus, Arctic skua Stercorarius parasiticus, Arctic tern Sterna paradisaea and Brünnich's guillemot Uria lomvia.

Land birds are fewer and also typical for the area, they include: Canada goose Branta Canadensis, wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe, snow bunting Plectrophenax nivalis, Lapland bunting, Calcarius lapponicus, redpoll Carduelis rostrata, and raven Corvus corax. The Greenland white-fronted goose Anser albifrons flavirostris summers only in west Greenland. Peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus, gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus, and rock ptarmigan Lagopus mutus are believed to occasionally breed in the area, while Arctic redpoll Carduelis hornemanni is a winter visitor. The red-throated diver Gavia stellata, great northern diver Gavia immer, mallard Anas platyrhynchos, long-tailed duck Clangula hyemalis, rednecked phalarope Phalaropus lobatus and the purple sandpiper Calidris maritima are believed to nest in the area, but at present no information is available to confirm this.

There are few mammals within the locality. Arctic fox Alopex lagopus is believed to be common, while Arctic hare Lepus arcticus occur mainly in the higher land near the inland ice. Reindeer Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus live only to the south of the icefjord, and polar bears Ursus maritimus are very rare visitors.

Cultural Heritage

Greenland has been inhabited for 4,500 years, settlers migrating from Asia via the Bering Straits and northwest Greenland in three main waves, known as the Saqqaq, Dorset and from 1000 BP, the Thule peoples. Their middens are shown in clear section at the Thule settlement of Sermermuit near Ilulissat. Norsemen inhabited southwest Greenland between 985-1450 AD. During the 16th-18th centuries explorers followed by whalers inhabited the area. The nominated area includes the archaeologically valuable sites of Sermermuit, abandoned in 1850, and Qajaa on the south side of the fjord, abandoned earlier. The early settlers summered in tents but used stone and turf hovels in winter. The first local Danish settlement was in 1742 at Jakobshavn, now Ilulissat.

Local Human Population

There are no inhabitants living within the boundaries of the nominated area. The local population of the Municipality is estimated at 4,800. Approximately 4,200 people inhabit Ilusissat (the third largest town in Greenland) the remaining population inhabits four villages: Ilimanaq, Oqaatsut, Qeqertaq and Saqqaq. Apart from the Danes, the local people are Inuit and their economy is almost entirely dependent on fishing and hunting. Their main prey are reindeer, seal, ptarmigan, hare, fox, geese, ducks, seabirds and birds eggs. Nowadays the local population are more sedentary but still move out to hunting grounds in summer to fish or hunt, especially for reindeer. There is a population of 4,000 sledge dogs. Winter hunting for ringed seal is undertaken at holes in the ice and by stalking. Since 1900 professional long-line fishing has centred on the Greenland halibut which flourishes in the turbulence around the calving bergs, the highly productive source of invertebrate prey for seals and fish. The halibut is fished in great concentrations round the fjord mouth. Some income is also beginning to accrue from tourism partly as an insurance against lean years in the fishing industry.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The scenery, Inuit culture and history attract a third of all Greenland's visitors to the Ilulissat and Disko areas. However it is the icefjord that is the main attraction. The government discouraged tourism until mid-century. It has only been actively promoted since 1992. In 1998 Ilulissat was designated by the Greenlandic Board of Tourism as the center for development in Greenland. Visitor facilities are improving, although they remain somewhat limited. In 2000 an estimated 10,660 tourists visited Iluissat (34% of all visitors to Greenland) and by 2005 an estimated 20,000 are expected to visit the area. Access to Ilulissat is by air, ferry and cruise ship (20-500 passengers and 18 ships in 2001). Local expeditions are made in to the surrounding environment, including the Icefjiord, by boat, helicopter, dog-sledge and by foot. Cross-country skiing and sailing are offered but snow scooters can only be used outside the nominated area. There are four hotels, a hostel and cabins, a museum of local history and guided tours. A visitor center is being planned in the town.

Scientific Research and Facilities

Scientific researches over 250 years have made Ilulissat Icefjord and surroundings one of the best observed ice streams in the world. A significant and unique set of glaciological records and many scientific publications have been written about the site which displays most of the surface characteristics of the Greenland ice margin clearly, compactly and accessibly. From the relatively ice-free mid 18th century onwards, the Icefjord interested many scholars, including Rink, Nordenskjiold, Hammer, Peary and Wegener, who noted its fluctuations over the years. Study, especially over the last 10-20 years using aerial photography, core drilling, deep radar sounding and satellite monitoring, has been intensive. Such research has enlarged understanding of ice-stream dynamics, glacial erosion and deposition, Quaternary geology and prehistoric climates through the examination of ice cores. Research into the local fauna has in contrast been far less. With concern over monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment) global climate change, Ilulissat will have much to offer in future. Moreover, understanding the area's 4500 years of human history, evident in the archaeological sites, illustrates the interplay between glacial movements and human migration.

Conservation Value

The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of an actively calving ice sheet which illustrates glacial conditions characteristic of the last Ice Age of the Quaternary. The ice stream is the fastest and most productive in the northern hemisphere, annually calving at the high velocity of 7 km per year over 40 km3 of ice, 10% of the calf ice of the Greenland ice cap and more than any other glacier outside Antarctica, Its other distinctive characteristic is the intensive erosion by the ice stream which is the world's outstanding example of a large-scale fjord-forming process. The wild and dramatic combination of rock, ice and sea in the ice-choked fjord, with the sounds of moving ice, are a memorable spectacle. The glacier is also unusually well studied and, being relatively accessible, has added much to the understanding of ice cap glaciology.

Conservation Management

The overall management and responsibility for the protection of nature in Greenland rests with the Greenland Parliament. The Ministry of Environment and Nature has overall responsibility for managing rules and regulations in nationally protected areas, including the supervision of local management in the municipalities.

If the protected area becomes a World Heritage Site, a board consisting of representatives from The Ministry of Environment and Nature, and from Ilulissat Municipality will be set up to have the overall responsibility in regard to the site's status. Ministry of Culture (UNESCO-authority) and the Danish UNESCO authorities will be connected on an advisory basis and take part in a yearly board meeting.

At site level, management of Ilulissat Icefjord will be under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environment and Nature and the Municipality of Ilulissat (The Department of Technics). Management in regard to the management plan will be carried out by the Municipality of Ilulissat The World Heritage board will ensure that the area and the management continuously live up to the standards that are necessary regarding its status as a World Heritage site. The board will appoint a site manager, who will have daily management responsibility and will be the contact person in regards to all matters concerning the site. The site manager position will be located in Ilulissat Municipality, but will be in close contact with the national authorities.

Staff

Game wardens responsible for the control of fishing and hunting along the coast are employed by the Greenland government and additional staff from the Municipality work on a part-time basis. Other staff trained in conservation and natural resource management are present in Greenland. They include those at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.

Budget

Financial information about the nominated area is not available. At present funds to support the daily management of the area by the Municipality of Ilulissat, come from the state via the Ministry of the Environment and Greenland Home Rule.

IUCN Management Category

- Natural World Heritage Site Natural criteria i, iii

Further Reading

- AMAP (1997). Arctic Pollution Issues. Oslo.

- Born, E.& Bocher, J. (2001). The Ecology of Greenland.. Ministry of Environment. Nuuk. 429pp.

- CAFF. (2002). Protected Areas of the Arctic-Conserving a Full Range of Values. Ottawa;

- CAFF. (1994). Protected Areas in the Circumpolar Arctic. Directorate for Nature Management, Norway;

- Greenland Tourism Website

- Hansen, K.(2002). A Farewell to Greenland's Wildlife. Copenhagen. 154pp.

- IUCN (2003). Global Strategy for Geological World Heritage sites. Draft.

- Nikkelsen, N.(ed.) (2003). Nomination of the Ilulissat Icefjord for Inclusion in the World Heritage List.

- Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Ministry of the Environment, Copenhagen.(This contains a bibliography of 267 references.)

- Nowlan, L. (2001).Arctic Legal Regime for Environmental Protection. IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper 44.

- Nordic Council of Ministers (1996). The Nordic Arctic Environment-Unspoilt, Exploited, Polluted? ISBN: 9291209023

- Nordic Council of Ministers (1999). Nordic Action Plan to Protect the Natural Environment and Cultural Heritage of the Arctic. Oslo. 95pp.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |