Early Exploration of Antarctica

| Topics: |

Exploration of the Antarctic - Part 3

See also Chronology of Antarctic Exploration.

Following the discovery of the South Shetland Islands in February 1819, seal hunters rushed to the islands and began arriving a few days ahead of the first charting expedition conducted by Edward Bransfield and William Smith in January 1820. The sealers were busy killing seals for their fur skins and oil while Bransfield and Smith went about the business of charting. The cartographers moved south to sight the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula three days after the expedition of Thaddeus von Bellinghausen had sighted the Antarctic coast for the first time, about 1,400 miles to the east. There is no clear evidence that the handful of sealers added anything to the exploration of the Antarctic during that first season.

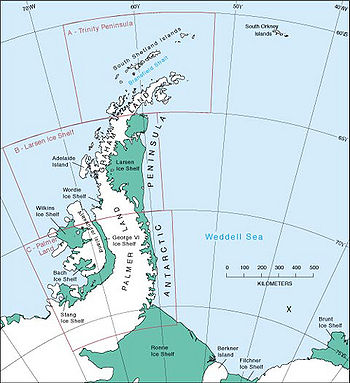

The rich rewards reaped by the first sealers during the 1819/20 summer season became widely known as soon as they returned to port and caused the equivalent of a "gold rush" late in 1820. Over fifty American and British sealing boats descended on the islands and set about claiming beaches with prime rookeries and slaughtering every seal. A twenty-one year-old Nathaniel Palmer, who had participated in the first season, returned as part of a small American fleet. Placed in command of a small (47 feet long) sloop Hero, and sent to find for a safe harbor, he sailed south from the South Shetlands along a similar path as Smith and Bransfield. On November 16-17, 1820, Palmer and his crew became the third to sight the coast of Antarctic Peninsula.

In an interesting twist of fate, Palmer and Bellinghausen actually met on February 6, 1821, near Deception Island in the South Shetlands. Palmer went aboard the Russian's ship and talked with Bellingshausen before returning to his sloop. It was later claimed that the Russian acknowledged the American as the discoverer of Antarctica, something accepted only by a small number of Palmer advocates.

As they decimated the seal populations on their breeding grounds, sealers explored nearby islands and further south. However, these discoveries were often shrouded in secrecy to maintain an advantage over competitors about where the best hunting grounds were. Perhaps the most notable example of this is the case of American sealer John Davis.

Arriving at the South Shetlands in late 1820, Davis found most of the best beaches occupied and being agressively defended other hunters. After several weeks, supplies of seals were rapidly dwindling, so Davis began exploring fornew sites. This included an excursion south in the Huron's support vessel, the Cecilia (support vessels were typically carried from port in pieces on the main vessel and assembled at the Falklands or somewhere else near the hunting grounds). On February 7, 1821, Davis sent a boat of men ashore on a region of land looking for seals. Finding none, the men returned after an hour to the Cecilia. Davis noted in the log, "I believe this Southern Land to be a Continent." Based upon his recorded position, Davis was in what is now named Hughes Bay, on the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. Davis did not publicize the landing.

In 1895, a group of Norwegian whalerslanded at Cape Adare,Antarctica and were acknowledged the first to put foot on the continent's mainland until historians discoveredDavis' log of the Huron in 1952.

The British captain, James Weddell, participated successfully in the seal hunts of 1820–1821 and 1821–1822. In the third summer season, finding the seal populations on the South Shetland Islands devastated, Weddell led two ships in a search of new grounds into the area east of the Antarctic Peninsula (now known as the Weddell Sea) and, in an unusually mild summer, was able to proceed as far south as 74°15’S before turning north. Weddell formed a different opinion from Cook and argued that the Southern Ocean probably contained islands and shallows filled with ice, with enough open sea to possibly sail to the South Pole.

In 1830, Nathaniel Palmer returned to the Antarctic as commander of the South Sea Fur Company and Exploring Expedition, a private venture motivated partly by commercial interests (the seal population of the South Shetlands had been decimated in a just few season's hunting) and partly by an odd theory that "holes" existed near the poles leading to other worlds inside the earth which could be settled and traded with. The expedition was, for the most part, a failure, but one member of the expedition, James Eights collected fossils on the South Shetland Islands, a first and significant find.

The British whaling company Enderby Brothers was particularly supportive of its captains' engaging in explorations (to such a degree that it contributed to their ultimate financial failure). In December 1824, an Enderby ship, the Sprightly charted parts of the Trinity Peninsula. In 1830-2, one Enderby captain, John Biscoe, completed the third circumnavigation at high southern latitudes, after Cook and Bellingshausen. In a journey with two small ships and a combined crew of just twenty-nine, Biscoe was able to chart a region of coast south of the Indian Ocean which he named Enderby Land in February 1831. A year later, he also charted various islands off the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula (Adelaide Island, Biscoe Islands, and Pitt Islands) and claimed the territory for Britain (Graham Land).

In late 1833, a non-Enderby British sealer Peter Kemp sighted land further east of Biscoe's in Enderby Land, now known as the Kemp Coast.

Also, it was an Enderby captain John Balleny that, in early 1839, discovered the Balleny Islands and sailed steadily west through the ice achieving a single sighting of the Sabrina Coast. One of Balleny's two ships was lost with all hands in a storm.

Charles Enderby gathered together the various sightings of land between 66°S and 68°S by sealers Biscoe (47°E to 51°E), Kemp (58°E), Balleny (121°E), with the belief that icebergs observed with rocks indicated land farther south. Enderby put forth the case that a continental coast existed between those latitudes extending around much of the globe, though farther south in the regions probed by Cook and Weddell, and farther north in the region of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Nonetheless, all that was really known were a few short dashes of land separated by a lot of ice. Whether a single, vast continental land massor an archipelago of frozen islands existed, truly could not be said.

Further Reading

- Below the Convergence: Voyages Towards Antarctica, 1699-1839, Alan Gurney, W.W. Norton and Company, 1997 ISBN: 0393039498.

- The Race to the White Continent, Alan Gurney, W.W. Norton and Company, 2002 ISBN: 0393323218.

- The Voyage of the Huron and the Huntress; The American Sealers and the Discovery of the Continent of Antarctica, Edouard A. Stackpole, Marine Historical Association, 1955

- South Pole: A Narrative History of the Exploration of Antarctica by Anthony Brandt, NG Adventure Classics, 2004ISBN: 0792267974.

- Exploring Polar Frontiers: An Historical Encyclopedia, William James Mills, ABC-CLIO, 2003 ISBN: 1576074226.

- Index to Antarctic Expeditions, Scott Polar Research Institute, retrieved November 1, 2008

- Antarctic History, Polar Conservation Organization, retrievedFebruary 16, 2009

- A Voyage Towards the South Pole, Performed in the Years 1822-24; Containing an Examination of the Antarctic Sea (1827), James Weddell, David & Charles, 1970

- The first landing on the mainland of Antarctica, Australian Antarctic Data Center, retrieved November 1, 2008

- Antarctic History, Antarctica Online, retrieved February 16, 2009

- The Antarctic Circle,retrieved February 16, 2009