William Smith

Smith, William

| Topics: |

William Smith (1790 - after 1847) was a British merchant sea captain who contributed to the exploration of the Antarctic by discovering the South Shetland Islands. He was one the of first people to sight the Antarctic continent.

Little is known about Smith's early life. He most likely served a seven year apprenticeship between the ages of 14 and 21, perhaps on ships moving coal. He may have also served on a whaling ship working off Greenland. In 1811, Smith gained command of his first ship, transporting coal. A year later, he took command of the Williams, which he commanded for nine years and during his discoveries in the Southern Ocean. By 1815, the Williams was crossing the Atlantic to various ports in South America.

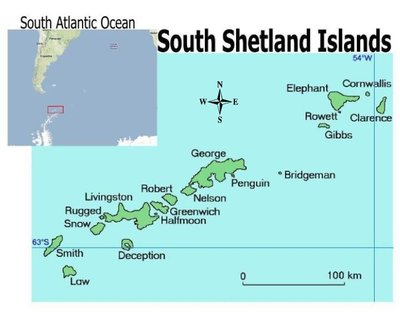

In January, 1819, the Williams, began a trip from Buenos Aires to Valparaiso. Facing adverse winds, Smith took the Williams, well south into the Drake Strait. On February 19, five hundred miles south of of Cape Horn, Smith reported "land or Ice was discovered" during a storm. On the following day, Smith, observed several islands with rough shorelines and peaks, as well as whales and seals in large numbers. In port, Smith reported his discovery to a British naval captain, William Henry Sheriff and to likely to others in port. The news of a possible new source of prized seal pelts began to spread.

On his return journey to Montevideo in June, Smith attempted to return to the islands when ice formed in the waters around his ship (it was winter in these waters) he turned north before getting close enough to see the islands. In Montevideo, people were already talking about the islands that Smith had observed and tried to get a detailed location from him. He appears to have refused to give details.

In late September, 1819, Smith again headed for Valpariaso and returned to the islands. This time he took soundings of the sea bottom to provide additional evidence that what he was seeing was indeed actual land rather than icebergs (a common mistake). From October 16 until October 18, Smith named and roughly charted several islands over about 160 miles before resuming his journey to Valparaiso. On arrival, Smith reported his discoveries to Captain Thomas Searle of the British navy who prevented contact with the shore until Sherff's return. Sheriff immediately commissioned the Williams to conduct a voyage of exploration to the islands and added several naval officers to the ship under the command of Edward Bransfield. Sheriff also reported up the chain of command to the British Government news of Smith's discovery of the South Shetland Islands.

In January, 1820, the Williams arrived back at the South Shetlands and began to chart them from the north side and then from the south side before reaching Deception Island. There were several landings and claiming of the islands for the British crown.

The Williams was not alone in the South Shetlands. News of Smith's discovery had already reached sealers and boats, British and American, began to arrive to hunt at the same time Bransfield was charting the islands. With a few important exceptions, little is know about what seal hunting ships discovered, because they were very competitive and therefore secretive about were they found seals.

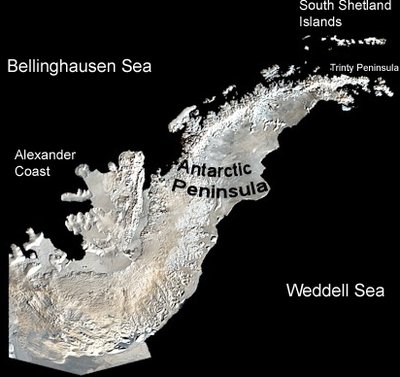

From Deception Island, the Williams sailed south across a stretch of water now known as the Bransfield Strait and on January 30, 1820, Smith and Bransfield again sighted land. Ahead lay an island (Tower Island) and beyond it more land with high peaks, which they named Trinity Land (now know as Trinity Peninsula , which is the northern most part of the Antarctic Peninsula and the Antarctic continent. Unknown to them, a Russian explorer, Thaddeus von Bellinghausen had probably sighted the Antarctic continent for the first time just three days earlier about 1,400 miles east of the Antarctic Peninsula.

For the next few days, the Williams sailed north and east paralleling the coast of the Trinity Peninsula without seeing much through the ice and fog before discovering Elephant Island and Clarence Island. After sailing further east and discovering nothing, the Williams returned to Valparaiso.

Bransfield's log and chart were forwarded to the Admiralty (though the log was subsequently lost) and reports began to appear in the British press. The first hand account of the journey, in the was produced by Charles Poynter one of the Midshipmen serving under Bransfield, entitled The Discovery of the South Shetland Islands, 1819-1820.

In December, 1820, Smith returned to the South Shetland Islands one more time to hunt seals and found "from 15 to 20 British ships, together with about 30 sail of the Americans". Hunters would decimate the seals of the South Shetlands in a few years. The Williams returned to London in September, 1821 with 30,000 seal skins. Unfortunately for Smith, his business partners were already in financial difficulty and his profitable journey could not save them or him. In June, 1822, the Williams was sold.

Smith became a pilot on the Thames River and elsewhere before gaining command of a whaling ship. Smith, like many sealers, did well for a few years, before again losing his ship.

In 1840, Smith petitioned the British Admiralty for a fund in compensation for his discoveries, but received nothing. In 1847, he wrote a will. The date of his death is unknown.

Further Reading

- Antarctica Observed, A.G.E. Jones, Caedmon of Whitby, 1982 ISBN: 0905355253.

- The Discovery of the South Shetland Islands, 1819-1820: The Journal of Midshipman C. W. Poynter, R. J. Campbell (editor), Hakluyt Society, 2001

- Below the Convergence: Voyages Towards Antarctica, 1699-1839, Alan Gurney, W.W. Norton and Company, 1997 ISBN: 0393039498.

- Exploring Polar Frontiers: An Historical Encyclopedia, William James Mills, ABC-CLIO, 2003 ISBN: 1576074226.

- Antarctica: Exploring the Extreme: 400 Years of Adventureby Marilyn J. Landis, Chicago Review Press, 2001 ISBN: 1556524285.