South Sea Fur Company and Exploring Expedition

| Topics: |

The South Sea Fur Company and Exploring Expedition of 1829-31 had two official purposes: it was a commercial enterprise launched in hopes of locating and exploiting new seal rookeries in and around the Antarctic; and its secondary goal was to introduce 19th-century scientific analysis to that recently discovered, cold, and forbidding continent. Neither ambition was fully realized; the rugged terrain did not produce significant sources of new wealth or knowledge, a consequence of the difficult conditions in which the sealers and scientists operated and the tension that existed in the expedition’s paired but hardly convergent goals.

Notwithstanding its formal name and ambitious aims, the expedition was an odd enterprise. Originally it was proposed to be a U.S. government-funded voyage, which would have made it the first federally sponsored scientific expedition in the new republic’s brief history. Its initial goal was even more unusual—to test whether the hollow-earth theories of John Cleves Symmes, later promoted with great energy by Jeremiah N. Reynolds, were accurate. In 1818, Symmes had declared that the interior of the earth was habitable, “containing a number of solid and concentrick spheres, one within the other.” He was convinced that the unexplored poles would provide literal openings to an inner terra icognita: “I pledge my life in support of this truth,” he announced “TO ALL THE WORLD” in his Circular Number 1, “and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.”

It almost complied: Reynolds, a journalist and late convert to Symmes’ theory, proved a deft advocate, and although the two men ultimately fell out, by 1827 Reynolds had succeeded in generating a popular groundswell for a publicly funded exploratory mission that would combine commercial, naval, and scientific ends. In May 1828, a galvanized House of Representatives resolved that the Navy should send a single vessel to explore the region, but significantly offered no dedicated funding for the exercise. Then, in the aftermath of Andrew Jackson’s election to the presidency in November 1828, South Carolina Senator Robert Y. Haynes blew the proposed voyage out of the water. He cast doubt on its constitutionality and denounced it as a waste of public funds.

Lacking federal dollars, the expedition’s scale and focus shrank: Stonington, Connecticut commercial agents, including wealthy merchant Edmund Fanning, whose vessels already had been committed to the journey, now provided the requisite financial backing. That being so, the underwriters expected a return on their investment, selecting experienced sealing captains and ships that would set sail in October 1829, a departure timed so as to arrive in the southern seas during the summer. Nathaniel Palmer, who had completed three profitable voyages to the southern seas, and captained the Annawan, had overall command; his brother Alexander captained the schooner Penquin; and one of Fanning’s business partners, Benjamin Pendleton, commanded the brig Seraph. The pursuit of seal hides and oil—not ideas, whatever their merit—now defined the project’s aspirations.

Still, the new sponsors did not neglect the expedition’s science-based origins. As Captain Palmer’s biographer put it: “Granting that the sealers and the whalers had a financial interest in a naval exploring expedition it is yet certain that they were also animated by a feeling of patriotic indignation over the supine attitude of Congress in the matter.” Moreover, among those sailing on the three-ship expedition was James Reynolds, who advised the New York Enquirer just before departing that once “the commercial objects of the expedition shall have been accomplished” he intended “to sail round the icy circle, and push through the first openings that he finds.” His enthusiasm and daring, the newspaper speculated, would advance human knowledge: the “stores of science will be increased by the products of far-distant islands, as yet unknown to civilized man, and curiosity may, perchance, be gratified by something new.” That “something new” would not be holes penetrating the earth’s mantle, but geological data and fossils unearthed by the only trained naturalist aboard, Dr. James Eights, whom the New York Enquirer described as a “gentleman of talents and scientific accomplishments.”

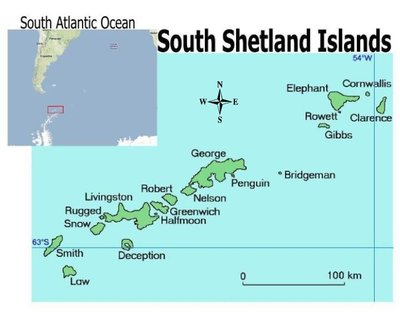

The voyage south went smoothly, and by January 1830 the Annawan, Penquin, and Seraph began to cruise in waters known and unknown. As they sailed in and around the South Shetland Islands, and to their west and south sought rumored, and uncharted, islands, they discovered few untapped rookeries. That should have come as no surprise: Stonington sailors for the past decade had been at the forefront of the wholesale slaughter of seals throughout the region, decimating their populations to such an extent that it would take decades for them to recover. This disappointment carried with it a pecuniary loss; because the crews operated on the “lay system,” their pay depended on the amount of hides and oil secured.

Mother Nature did not cooperate either. By late February, the weather had deteriorated, endangering the Americans’ survival:

“as the days passed Snow storm followed snow storm. The ice formed on deck and on the rigging so swiftly that the crews were obliged to cut it away to prevent foundering. It was with extreme difficulty that they could handle the ropes and sails. They were continuously wet with the freezing spray and there was no fire in either the cabin or the forecastle by which they could warm their stiffened limbs. But they persevered until the two brigs Annawan and Penguin had covered the region lying between the parallels of 52º and 62º 33’ south latitude and the meridians of 61º and 103º 03’ west longitude wherein the islands for which they were searching were supposed to lie.”

This disappointment was mirrored in the sailors’ declining health: “Many of the crew were disabled,” Captain Alexander Palmer wrote in his journal. “This cruise furnished an example that no sealer ever wished to imitate, namely to search for land southwest of Cape Horn.”

So battered were the crew and ships, so continually rough and icy were the waters and weather, that the three captains decided to head north to Chile to regroup, a decision made all the more compelling by the “alarming symptoms of that dread disease the scurvy making its appearance.” In protected Chilean ports, Benjamin Pendleton observed, it would be possible to “to refresh and recruit our men and to replenish our wood and water.”

Yet the sailors, once their health was restored, rebelled against launching off on the voyage’s proposed second stage, a cruise into the far northern reaches of the Pacific. Some deserted; others more mutinous, Palmer turned over the U. S. Consul in Valparaiso. Without enough hands to sail north, the diminished expedition headed south around the cape, arriving in Stonington by August 1831.

Among those who had remained behind in Chile was Jeremiah Reynolds; his investigations in the Antarctic had proved fruitless. Not so those of James Eights, the Albany-trained physician and geologist. His pioneering observations of the Antarctic’s geology, paleontology, and biology included descriptions of three new invertebrate species of crustacea and the description of the first plant fossils; trilobite specialist Riccardo Levi-Setti has praised Eights “meticulously described” and “detailed ink drawings” of the fossils he collected; and Levi-Setti is among a number of scholars who have applauded Eights precise recreations of the “vivid color the misty, frigid yet sublime atmosphere and scenery of these Antarctic shores being seen for the first time.” Although Eights discoveries were little known in his time, in part because they were published in hometown newspapers, local journals, and regional scientific proceedings, his studies, historian Stephen Pyne has confirmed, “inaugurate the scientific assimilation of the Antarctic.”

The expedition’s commercial exploits were less substantial. On August 29, 1831, the Seraph’s cargo was auctioned off: “She had brought home 2,024 skins of the fur seal and 13,000 of the hair seal,” but what this cargo fetched at market is unknown; and there is no accounting of the haul of either the Annawan or Penguin. Palmer’s biographer, however, reasons that because these latter two ships “were at the Shetlands in advance of the Seraph and also arrived on the coast of Chile in advance of it is reasonable to suppose they did at least as well as Captain Pendleton The Seraph,” he concludes that it “is likely that a small profit was realized out of expedition."

Without gainsaying such material returns—however slight—the shrewd Captain Pendleton knew that profit should not have been the driving force behind the South Sea Fur Company and Exploring Expedition of 1829-31: “an exploring expedition, under private means, never can produce any great or important national benefits, the same must be under the authority from the government, and the officers and men under regular pay and discipline, as in the navy.”

This ambition was finally realized in August 1838, when under the command of Lt. Charles Wilkes, the United States Exploring Expedition, and its small complement of scientists, set sail on a four-year-long voyage in the southern seas and the Pacific Ocean.

See also Exploration of the Antarctic.

References:

- The Race to the White Continent, Alan Gurney, W.W. Norton and Company, 2002 ISBN: 0393323218.

- Captain Nathaniel Brown Palmer an old-time sailor of the sea, John Randolph Spears, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922

- James Eights

- Research in the Antarctic, Louis O. Quam, Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1971

- Trilobites, Riccardo Levi-Setti, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 68-9; 71;

- The Ice: A Journey to the Antarctic, Stephen J. Pyne, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1986, p. 17-18; 76; 151.