Sonoran Desert

The Sonoran Desert covers approximately 200,000 square miles (520,000 square kilometers), including about 100,000 square miles of land, and often defined to also cover around 100,000 square miles of sea; moreover, the Sonoran comprises much of the state of Sonora, Mexico, most of the southern half of the USA states of Arizona, southeastern California, most of the Baja California peninsula, and the numerous islands of the Gulf of California. Its southern third straddles 30° north latitude and is a horse latitude desert; the rest is rainshadow desert. It is lush in comparison to most other deserts. There is a moderate diversity of faunal organisms present, with 550 distinct vertebrate species having been recorded here.

Subdivisions

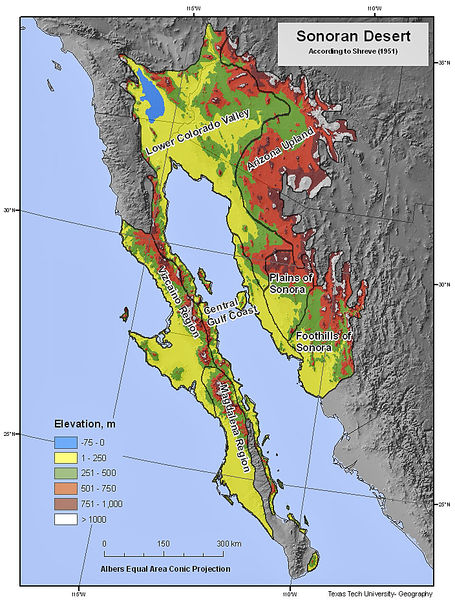

The Sonoran Desert can be divided into Seven subdivisions based on vegetation, according to a classification first advanced by Shreve (1951) and shown in the associated map. These ecoregions have sharp definition of vegetation type as well as geology and climate. The designations of these subdivisions are:

- Lower Colorado River Valley

- Arizona Upland

- Plains of Sonora

- Central Gulf Coast

- Vizcaino

- Magdalena

- Foothills of Sonora

Note that the Baja California elements, including the Vizcaino and Magdalena units, are sometimes treated as a separate ecoregion termed by the World Wildlife Fund as the Baja California Desert.

Landscape characteristics

Subdivisions of the Sonoran Desert, redrawn from Shreve (1951).

Subdivisions of the Sonoran Desert, redrawn from Shreve (1951).

The visually dominant elements of the landscape are two lifeforms that distinguish the Sonoran Desert from the other North American deserts: legume trees and large columnar cacti. This desertalso supports many other organisms, encompassing a rich spectrum of some 2000 species of plants, 550 species of vertebrates, and untolled thousands of invertebrate species. Much of the northern portion of the Sonoran Desert is drained by the Gila River.

The highest elevation in the western part of the ecoregion, which reaches 1206 meters in elevation, was created when intense volcanic activity adjacent to a portion of the Gulf of California produced a lava flow and numerous cinder cones surrounding the Pinacate area. The rest of the western section is composed of plateaus and sand dunes reaching no more than 200 meters (m) above sea level. The south-central part of the Mexican state of Sonora is dominated by the foothills of the western Sierra Madre Occidental. These mountains reach elevations between 1000 and 2000 m, resulting from a system of faults and generalized volcanic activity during the Cenozoic era. Soils are sandy and alkaline in the dunes, but toward the Pinacate and mountainous regions; moreover, they consist of either igneous or metamorphic material.

Climate

Vizcaino region by San Ignacio Lagoon. @ C.Michael Hogan The amount and seasonality of rainfall are defining meteorlogical characteristics of the Sonoran Desert. Much of the area has a bi-seasonal rainfall pattern, though even during the rainy seasons most days exhibit partialsunshine (Sunlight). From December to March frontal storms originating in the North Pacific occasionally bring widespread, gentle rain to the northwestern two-thirds. From July to mid-September, the summer monsoon brings surges of wet tropical air and localized deluges in the form of violent thunderstorms to the southeastern two-thirds. So distinct are the characters of the two types of rainfall that Sonoran residents have different Spanish terms for them. The winter rains are termed equipatas (derived from the Yaqui-Mayo word for rain, quepa), the summer rains are las aguas ("the waters" in Spanish).

Vizcaino region by San Ignacio Lagoon. @ C.Michael Hogan The amount and seasonality of rainfall are defining meteorlogical characteristics of the Sonoran Desert. Much of the area has a bi-seasonal rainfall pattern, though even during the rainy seasons most days exhibit partialsunshine (Sunlight). From December to March frontal storms originating in the North Pacific occasionally bring widespread, gentle rain to the northwestern two-thirds. From July to mid-September, the summer monsoon brings surges of wet tropical air and localized deluges in the form of violent thunderstorms to the southeastern two-thirds. So distinct are the characters of the two types of rainfall that Sonoran residents have different Spanish terms for them. The winter rains are termed equipatas (derived from the Yaqui-Mayo word for rain, quepa), the summer rains are las aguas ("the waters" in Spanish).

The climate of the Sonoran Desert ecoregion varies slightly due to its large areal extent. In the Arizona upland section, conditions are more mesic, with bi-seasonal precipitation between 100 to 300 millimeters annually. Climate is subtropical dry near the Gulf of California. Near the Colorado River Valley and all remaining parts of the ecoregion temperatures are high year round with infrequent, irregular rainfall creating an arid dry climate. The Desierto de Altar, in the western Sonoran ecoregion, is one of the most arid areas of North America, with periods of drought enduring up to 30 months. In general, the ecoregion is quite desiccated, often receiving less than 90 mm of annual rainfall.

Distinguishing characteristics

Saguaro Cacti. Carnegiea gigantea. Source: Mark A. Dimmitt. © 2002 The Sonoran Desert prominently differs from the other three deserts of North America in having mild winters. Most of the area rarely experiences frost, and the biota are partly tropical in origin. Many of the perennial plants and animals are derived from ancestors in the tropical thorn-scrub to the south, their life cycles attuned to the brief summer rainy season. The winter rains, when ample, support great populations of annuals (which make up nearly half of the plant species). Some of the plants and animals are opportunistic, growing or reproducing after significant rainfall in any season.

Saguaro Cacti. Carnegiea gigantea. Source: Mark A. Dimmitt. © 2002 The Sonoran Desert prominently differs from the other three deserts of North America in having mild winters. Most of the area rarely experiences frost, and the biota are partly tropical in origin. Many of the perennial plants and animals are derived from ancestors in the tropical thorn-scrub to the south, their life cycles attuned to the brief summer rainy season. The winter rains, when ample, support great populations of annuals (which make up nearly half of the plant species). Some of the plants and animals are opportunistic, growing or reproducing after significant rainfall in any season.Biodiversity

The Sonoran Desert has the greatest diversity of vegetative growth of any desert on Earth. At least 560 native plant species thrive in the extremely harsh conditions of drought and heat, and interact in a gamut of ecological relationships that add to the complexity of the community. There are a number of special status organisms that are found in the Sonoran Desert, variously denoted as Near Threatened (NT), Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), or Critically Endangered (CR). More than 160 plant species, including six threatened succulents, depend upon legumes such as ironwood and mesquite for their regeneration in the Sonoran Desert.

Flora

Creosote Bush (Larrea divaricata) and White Bursage (Ambrosia dumosa) vegetation characterize the lower Colorado River Valley section. The Arizona upland section to the north and east is more mesic, resulting in greater species diversity and richness. Lower elevation areas are dominated by dense communities of Creosote Bush and White Bursage, but on slopes and higher portions of bajadas, subtrees such as palo verde (Cercidium floridum, C. microphyllum) and Ironwood (Olneya tesota), saguaros (Carnegiea gigantia), and other tall cacti are abundant. Cresosote Bush (Larrea tridentata) and White Bursage (Ambrosia dumosa) form the scrub that dominates the northwest part of the Sonoran Desert. This association thrives on deep, sandy soils in the flatlands. Where the dunes allow for slight inclination of the slope, species of Mesquite (Prosopis), Cercidium, Ironwood (Olneya tesota), Candalia, Lycium, Prickly-pear (Opuntia), Fouquieria, Burrobush (Hymenoclea) and Acacia are favored. The coastal plains of Sonora are composed of an almost pure Larrea scrub. Away from the Gulf influence in the area surrounding the Pinacate, Encelia farinosa, Larrea tridentata,Olneya, Cercidium, Prosopis, Fouquieria and various cacti species dominate the desert. Epiphytes, mosses and lichens are scarce but not absent.

The Saguaro (Cereus giganteus) is clearly the most recognizable Sonoran Desert plant species, and the largest of all cacti. Other ot the many cacti species here are Cholla Cactus (Opuntia fulgida), Organ Pipe (Lemaireocereus thurderi), Silver Dollar Cactus (Opuntis chlorotica). The Gray Box Bush (Simmondsia chinensis) is another iconic plant of the Sonoran. The coastal plain area houses the Ironwood (Olneya tesota) which is the oldest desert tree in North America. It has also been demonstrated thatO. tesota and C. floridum provide nursing relationships that promote diversification and increase richness of other plants in this aridecosystem. Another remarkable plant found in the Sonora desert is the Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens), which may remain leafless during the coldest months of winter, but experiences five or six leafy periods throughout the year. The brilliant red conical flowers are triggered by the first cool-season rain in the spring, flowering within as few as 48 hours and attracting a myrian of hummingbirds and other nectar feeders.

Mammals

Many wildlife species, such as Sonoran Pronghorn Antelope (Antilocapra sonoriensis EN), Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) and the endemic Bailey's Pocket Mouse (Chaetodipus baileyi) use ironwood, cacti species and other vegetation as both shelter from the harsh climate as well as a water supply. Other mammals include predators such as Puma (Felis concolor), Coyote (Canis latrans) and prey such as Black-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus californicus), and the Round-tailed Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus tereticaudus). Other mammals able to withstand the extreme desert climate of this ecoregion include California Leaf-nosed Bat (Macrotus californicus) and Ring-tailed Cat (Bassariscus astutus).

Reptiles

Three endemic lizards to the Sonoran Desert are: the Coachella Fringe-toed Lizard (Uma inornata EN); the Flat-tail Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma mcallii NT); and the Colorado Desert Fringe-toed Lizard (Uma notata NT); an endemic whiptail is theSan Esteban Island Whiptail (Cnemidophorus estebanensis). Non-endemic special status reptiles in the ecoregion include the Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii VU) and the Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum NT).

Amphibians

The Desert Slender Salamander (Batrachoseps major aridus) is endemic to the Sonoran Desert. Other salamanders occurring in the Sonoran Desert are the Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) and the Tarahumara Salamander (Ambystoma rosaceum).

Great Plains Toad. Source: John H. Tashjian/ CalPhotos/EoL There are twenty-four anuran species occurring in the Sonoran Desert, one of which is endemic, the Sonoran Green Toad (Anaxyrus retiformis). Other anurans in the ecoregion are: California Treefrog (Pseudacris cadaverina); Canyon Treefrog (Hyla arenicolor); Lowland Burrowing Frog (Smilisca fodiens); Mexican Treefrog (Smilisca baudinii); Madrean Treefrog (Hyla eximia); Sabinal Frog (Leptodactylus melanonotus); Northwest Mexico Leopard Frog (Lithobates magnaocularis); Brown's Leopard Frog (Lithobates brownorum); Yavapai Leopard Frog (Lithobates yavapaiensis); Mexican Cascade Frog (Lithobates pustulosus); Mexican Leaf Frog (Pachymedusa dacnicolor); Red Spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus); Sinaloa Toad (Incilius mazatlanensis); Sonoran Desert Toad (Incilius alvarius); Eastern Green Toad (Anaxyrus debilis); New Mexico Spadefoot (Spea multiplicata); Great Plains Toad (Anaxyrus cognatus); Couch's Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchii); Cane Toad (Rhinella marina); Elegant Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne elegans); Little Mexican Toad (Anaxyrus kelloggi); Great Plains Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne olivacea); and Woodhouse's Toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii).

Great Plains Toad. Source: John H. Tashjian/ CalPhotos/EoL There are twenty-four anuran species occurring in the Sonoran Desert, one of which is endemic, the Sonoran Green Toad (Anaxyrus retiformis). Other anurans in the ecoregion are: California Treefrog (Pseudacris cadaverina); Canyon Treefrog (Hyla arenicolor); Lowland Burrowing Frog (Smilisca fodiens); Mexican Treefrog (Smilisca baudinii); Madrean Treefrog (Hyla eximia); Sabinal Frog (Leptodactylus melanonotus); Northwest Mexico Leopard Frog (Lithobates magnaocularis); Brown's Leopard Frog (Lithobates brownorum); Yavapai Leopard Frog (Lithobates yavapaiensis); Mexican Cascade Frog (Lithobates pustulosus); Mexican Leaf Frog (Pachymedusa dacnicolor); Red Spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus); Sinaloa Toad (Incilius mazatlanensis); Sonoran Desert Toad (Incilius alvarius); Eastern Green Toad (Anaxyrus debilis); New Mexico Spadefoot (Spea multiplicata); Great Plains Toad (Anaxyrus cognatus); Couch's Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchii); Cane Toad (Rhinella marina); Elegant Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne elegans); Little Mexican Toad (Anaxyrus kelloggi); Great Plains Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne olivacea); and Woodhouse's Toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii).

Avian species

The Sonoran Desert is recognized as an exceptional birding area within the USA. Forty-one percent (261 of 622) of all terrestrial bird species found in the USA can be seen here during some season of the year. The Sonoran Desert, together with its eastern neighbor the Chihuahuan Desert, is the richest area in in the USA for birds, particularly hummingbirds. Among the bird species found in the Sonoran Desert are the saguaro-inhabiting Costa's Hummingbird (Calypte costae), Black-tailed Gnatcatcher (Polioptila melanura), Phainopepla (Phainopepla nitens) and Gila Woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygualis). Perhaps the most well-known Sonoran bird is the Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), distinguished by its preference for running rather than flying, as it hunts scorpions, tarantulas, rattlesnakes, lizards, and other prey. The Sonoran Desert exhibits two endemic bird species, the highest level of bird endemism in the USA. The Rufous-winged Sparrow (Aimophila carpalis) is rather common in most parts of the Sonoran, but only along the central portion of the Arizona-Mexico border, seen in desert grasses admixed with brush. Rare in extreme southern Arizona along the Mexican border, the endemic Five-striped Sparrow (Aimophila quinquestriata) is predominantly found in canyons on hillsides and slopes among tall, dense scrub.

Ecological boundaries

The Sonoran Desert is bounded on the west by the Peninsular Ranges, which divide it from the California chaparral and woodlands ecoregion to the northwest, and Baja California desert - Vizcaino subregion, central and southeast ecoregions of the Pacific versant. To the north in California and northwest Arizona, the Sonoran Desert transitions to the colder-winter, slightly higher elevation Mojave Desert, Great Basin, and Colorado Plateau deserts. To the east and southeast, the desert transitions to the temperate coniferous forests of the Arizona Mountains and Sierra Madre Occidental pine-oak forests at higher elevations. Finally, to the south the Sonoran-Sinaloan transition subtropical dry forest is the ecotone from the Sonoran Desert to the Sinaloan dry forests of Sinaloa.

Ecological status

Ajo, Arizona, USA. (Photograph by The GLOBE Program)

Ajo, Arizona, USA. (Photograph by The GLOBE Program) Around sixty percent of habitat in the USA alone has been altered by agriculture, overgrazing by commercial livestock, groundwater overdrafting, trampling and rubbish accumulation from illegal human immigration, and urbanization. Riparian desert woodland [[habitat]s] have suffered the worst and are now one of the rarest habitats in North America. Residential development on bajadas is eliminating the habitat of bajada-dependent species such as Prickly-pear Cacti (Opuntia) and columnar cacti such as Saguaro. Rocky habitat areas preferred by Gila Monsters and Bighorn Sheep are also vulnerable. The last population of Sonoran Pronghorn is confined to the Cabeza area in southern Arizona, isolated by lack of connectivity with other habitat areas.

The dry, inhospitable nature of the Sonoran Desert has favored the preservation of large areas with original vegetation. Four protected areas have been established in the Mexican Sonoran Desert in the last two decades, but they occupy less than five percent (9540 square kilometers) of the original desert area. In the USA approximately seventeen percent of the Sonoran Desert is protected; however, near the Mexican border ranger patrols are lax, due to the dangers posed by intensive illegal narcotics trafficking and human immigration in remote desert areas.

The Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and Organ Pipe National Monument Biosphere Reserve, both in Arizona, and the four protected areas in the Mexican part of the Sonoran Desert ecoregion form the second largest protected area of xeric scrub in North America. Lack of connectivity between all protected areas within and across borders also remains a serious problem. Other areas that include wildlife refuges, national monuments and/or military installations are located in the Kofa Mountains, Lower Colorado River, Arrastra Mountains, Chuchwilla Mountains, Eagletail Mountains, and Turtle Mountain. In addition, there are large areas of intact habitat within the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation.

Ecological threats

Threats to the ecoregion include cattle overgrazing, trampling and disturbance from illegal narcotics trafficking and illegal immigration, groundwater overdrafting and urbanization. The urban and suburban areas of Phoenix and Tucson in the USA continue to expand rapidly. This in turn is pushing agriculture operations further into the desert and along riparian areas such as the Gila River, with considerable impacts on wildlife habitat. Riparian habitats are threatened by trampling, overgrazing and fouling by domestic livestock; water diversion and dam building; trampling and disturbance by large numbers of Mexican and Central American nationals moving clandestinely into the USA; and introduction of alien species such as the Tamarisk Tree (Tamarix chinensis). Overgrazing is exacerbated by USA federal policies, which often induce ranchers to bring in additional livestock to areas only marginally suited for grazing, by offering below market leases, subsidized by U.S. taxpayers. Furthermore, the introduction of invasive animal and plant species will displace native fauna and flora through direct competition.

The introduction of Buffel-grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), further stimulating cattle overgrazing, has been particularly destructive to desert grassland and cryptic crust soils; Buffel-grass residues accumulate, forming combustible litter that causes the complete burning of ironwood and other plants. As a result, arid grasslands replace the xeric scrub, thereby impeding the recruitment of perennials. If this practice remains uncontrolled, the landscape of the Sonoran Desert will change and biodiversity reduced. Another significant threat to the region is the widespread, illegal collection of plant and animal species of high biological value, and the uncontrolled hunting of endangered species such as mule deer, pronghorn antelope, and mountain sheep. Tourism activities in the region have become extensive, bringing increased danger of water pollution and disturbance of flora.

See also

Further reading

- A. Búrquez and M. A. Quintana. 1994. Islands of diversity: Ironwood ecology and the richness of perennials in a Sonoran Desert biological reserve.

- A. Challenger. 1998. Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México. Pasado, presente y futuro. ISBN: 9709000020

- CONABIO Workshop, 17-16 September, 1996. Informe de Resultados del Taller de Ecoregionalización para la Conservación de México.

- Mark A.Dimmitt. Biomes & Communities of the Sonoran Desert, Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum.

- A. Küchler. 1975. Vegetation maps of North America. Lawrence: University of Kansas Libraries.

- J.A. MacMahon. 1988. Warm deserts. North American terrestrial vegetation. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England.

- Forrest Shreve. 1951. Vegetation of the Sonoran Desert, Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 591

- Forrest Shreve and Ira L Wiggins. 1964. Vegetation and Flora of the Sonoran Desert. Stanford University Press

- Stanley D. Smith, Russell K. Monson, Jay Ennis Anderson. 1997. Physiological ecology of north american desert plants. Springer Publishing. 286 pages

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum and some information previously published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited that content and added substantial new information. The use of information from the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum and World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by those organizations for new information added by EoE personnel, or for editing of the earlier content. |