Arizona Mountains forests

ContentsWWF Terrestrial Ecoregions Collection |

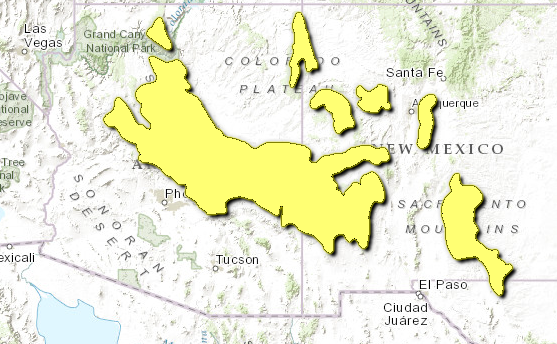

The Arizona Mountain Forests extend from the Kaibab Plateau in northern Arizona to south of the Mogollon Plateau into portions of southwestern Mexico and eastern Arizona. This ecoregion is an element of the Temperate Coniferous Forests biome. The species richness in this ecoregion is moderate, with vertebrate taxa numbering 375 species. The topography consists chiefly of steep foothills and mountains, but includes some deeply dissected high plateaus. Elevations range from 1370 to 3000 meters (m) with some peaks as high as 3840 m. Soil types have not been well defined; however, most soils are entisols, with alfisols and inceptisols in upland areas. Stony terrain and rock outcrops occupy large areas on the mountains and foothills.

Vegetation zones in this ecoregion resemble the Rocky Mountain Life Zones but at higher elevations. Although forests in this ecoregion are too far south to support distinct alpine communities, they exhibit a well-defined Transition Zone at 1980 to 2440 m in elevation, where a cool, moist climate supports pine forests above the drier pinyon-juniper-oak woodlands of lower elevations. These forests are both wet and cold, averaging 635 millimeters (mm) to 1000 mm with annual precipitation increasing in the upper elevation Canadian Zone. The growing season is typically less than 75 days with occasional nighttime frosts.

The Transition Zone in this region comprises a strong Mexican fasciation, including Chihuahua Pine (Pinus leiophylla) and Apache Pine (P. engelmannii) and unique varieties of Ponderosa Pine (P. ponderosa var. arizonica). Such forests are open and park-like and contain many bird species from Mexico seldom seen in the U.S.. The Canadian Zone (above 2000 m) includes mostly Rocky Mountain species of mixed-conifer communities such as Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmanni), Subalpine Fir (Abies lasiocarpa), and Corkbark Fir (A. lasiocarpa var. arizonica). Dwarf Juniper (Juniperus communis) is an understory shrubby closely associated with spruce/fir forests. Exposed sites include Chihuahua White Pine (Pinus strobiformis), while disturbed north-facing sites consists primarily of Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta) or Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides).

Virgin forests in this region often exceed 25 m in height and are commonly layered in two or more age classes. Below 2900 m elevation, one or more of the age classes may be composed solely of Quaking Aspen, an important wildlife habitat component and pioneer species following fire. Wetter sites contain Rocky Mountain Maple (Acer glabrum), Bebb Willow (Salix bebbiana), Scouler Willow (S. scouleriana), Blueberry Elder (Sambucus glauca), thin-leafed alder (Alnus tenuifolis), or bitter cherry (Prunus emarginata). Dry windy sites may be occupied by Limber Pine (P. flexis) and Bristelcone pine (P. aristata). At lower elevations (less than 2600 m) Douglas-fir intermingles with Ponderosa Pine and White Fir (Abies concolor).

Biological distinctiveness

Coyote. Source: Lloyd Glenn Ingles, California Academy of Sciences and CalPhotos

Coyote. Source: Lloyd Glenn Ingles, California Academy of Sciences and CalPhotos In general, this ecoregion was considered regionally outstanding because of its relatively high level of species richness (2817 taxa) and endemism (132 taxa). Plants were the richest (78% of the total species) taxa, followed by birds (7%) and butterflies (7%), snails (3%) and mammals (3%). Most (26%) endemic taxa of the ecoregion are plant species.

This ecoregion was also the southern extent of spruce/fir forests and northern extent of many Mexican wildlife species, including tropical birds and reptiles. The Gila Wilderness in southwestern New Mexico contains perhaps the largest and healthiest ponderosa pine forest in the world. The region exhibits outstanding subterranean biodiversity, with an extensive cave fauna in Guadalupe. Of local conservation importance is the status of riparian areas. Riparian areas, in general, represent less than one percent of southwestern landscapes yet are critically important to wildlife, water quality, and fish habitat.

Mammals

Arizona Gray Squirrel. Source: B.J. Stacey/ iNaturalist/ EoL There are a variety of mammalian species found in this ecoregion, including the endemic Arizona Gray Squirrel (Sciurus arizonensis), an herbivore (Herbivore) who feeds on a wide spectrum of berries, bark and other vegetable material. Non-endemic mammals occurring in the ecoregion include: the Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys spectabilis NT);Desert Pocket Gopher (Geomys arenarius NT). In addition, there is great potential for restoring Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus) and Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) populations in the area because of its remoteness and juxtaposition to other ecoregions where these species were formerly prevalent.

Arizona Gray Squirrel. Source: B.J. Stacey/ iNaturalist/ EoL There are a variety of mammalian species found in this ecoregion, including the endemic Arizona Gray Squirrel (Sciurus arizonensis), an herbivore (Herbivore) who feeds on a wide spectrum of berries, bark and other vegetable material. Non-endemic mammals occurring in the ecoregion include: the Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys spectabilis NT);Desert Pocket Gopher (Geomys arenarius NT). In addition, there is great potential for restoring Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus) and Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) populations in the area because of its remoteness and juxtaposition to other ecoregions where these species were formerly prevalent.

Reptiles

A number of reptilian taxa occur in the Arizona mountains forests, including: Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum NT), often associated with cacti or desert scrub type vegetation; Narrow-headed Garter Snake (Thamnophis rufipunctatus), a near-endemic found chiefly in the Mogollon Rim area; Sonoran Mud Turtle (Kinosternon sonoriense NT).

Jemez Mountains Salamander. Source: Todd Pierson /EoL Amphibians

Jemez Mountains Salamander. Source: Todd Pierson /EoL Amphibians

There are few amphibians found in the Arizona mountain forests. Anuran species occurring here are: Red-spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus); Southwestern Toad (Anaxyrus microscaphus); New Mexico Spadefoot Toad (Spea multiplicata); Woodhouse's Toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii); Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens); Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis VU); Madrean Treefrog (Hyla eximia), a montane anuran found at the northern limit of its range in this ecoregion; Boreal Chorus Frog (Anaxyrus woodhousii); Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata); and Canyon Treefrog (Hyla arenicolor). The Jemez Mountains Salamander (Plethodon neomexicanus NT) is an ecoregion endemic, found only in the Jemez Mountains of Los Alamos and Sandoval counties, New Mexico. Another salamander occurring in the ecoregion is the Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum).

Conservation status

Habitat loss and degradation

In general, the ecoregion was considered relatively stable with approximately 25 percent of it still intact. However, several threats to the ecoregion were identified by workshop participants and the published literature, including:

- Deforestation and related fragmentation of old growth and roadless areas

- Severe overgrazing in wilderness areas

- Heavily degraded stream channels and loss of habitat for the endangered Gila Trout (Oncorhynchus gilae EN) and Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus).

- Global endangerment of Fremont Cottonwood (P. fremontii) and Goodding Willow (S. gooddingii). These trees grow chiefly in wet soils in riparian zones.

- Timber harvest in mature and old growth forests preferred by the Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidentalis lucida and northern goshawk (Accipiter gentalis) (particularly on the Kaibab Plateau).

Remaining blocks of intact habitat

Several sizable blocks of intact habitat remain in this ecoregion including the following areas:

- Aldo Leopold-Gila Wilderness - southwestern New Mexico

- Blue Range Primitive Area - eastern Arizona

- Guadalupe-Carlsbad area - southeastern New Mexico and western Texas

- Kaibab Plateau and national forest - north-central Arizona

- Grand Canyon National Park - northwestern Arizona

- Chuska Mountains on Navajo lands - northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico

- Mazatzal Complex - central Arizona

- Superstition Mountains - central Arizona

- El Malpais National Monument and Conservation Area - western New Mexico

In addition, Foreman and Wolke identified several large (40,000 hectares or more) roadless areas, including:

- Sycamore Canyon-Secret Mountains: North-central Arizona

- Hellsgate: Central Arizona

- Four Peaks: Central Arizona

- Salt River: Baldy Bill - central Arizona

- Eagle Creek: Gila Mountains - eastern Arizona

- Galiuro Mountains: Eastern Arizona

Degree of fragmentation

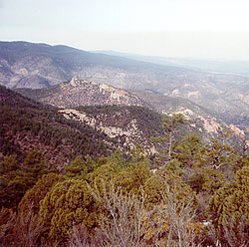

Near Gila Wilderness, Sierra Madre, New Mexico. (Photograph by John Morrison) Habitat fragmentation in this region has been primarily related to timber harvest in roadless areas and old age forest classes. Several areas were recommended by workshop participants as potential corridors for minimizing fragmentation and insularization effects, including connecting the Gila complex with the Sky Islands to the south for future wolf movements; connecting the Gila complex with the Mataxal complexes at Showlow, New Mexico, and also connecting riverine habitat through stream buffers designed to restore degraded fish populations.

Near Gila Wilderness, Sierra Madre, New Mexico. (Photograph by John Morrison) Habitat fragmentation in this region has been primarily related to timber harvest in roadless areas and old age forest classes. Several areas were recommended by workshop participants as potential corridors for minimizing fragmentation and insularization effects, including connecting the Gila complex with the Sky Islands to the south for future wolf movements; connecting the Gila complex with the Mataxal complexes at Showlow, New Mexico, and also connecting riverine habitat through stream buffers designed to restore degraded fish populations.

Degree of protection

The large wilderness areas identified above are largely protected from logging; however, grazing continues to be a concern in some wilderness areas. One of the chief drivers of overgrazing is an ongoing practice of the USA federal government of letting grazing rights at below market rates; this practice not only encourages overgrazing of lands of marginal value, but also causes the U.S. taxpayer to subsidize this environmental destruction (Habitat destruction). In general, about nine percent of the ecoregion is in areas permanently protected from industrial logging and mining.

Ecological threat profile

There are several threats to the ecoregion, including land conversion (road building,timber harvesting); degradation (fire suppression, mining, ORV use, logging, fuel gathering); and potential wildlife losses (high threat to future Mexican wolf reintroduction from poaching). Additional threats to riparian areas, and old growth forests and roadless areas were identified in the literature.

Suite of priority activities to enhance ecological conservation

Within this ecoregion the best opportunities for conservation include the following:

- Control overgrazing on the Diamond Bar allotment in the Gila Wilderness

- Eliminate governmental grazing leases at below market rates

- Protect and restore degraded native fish populations, particularly endemic trout through habitat restoration in degraded riparian areas

- Protect remaining old growth and roadless areas

- Promote reintroduction of the Mexican Wolf and maintain habitat connections across ecoregions of suitable occupation

- Designate the Blue Range Wilderness area as protected

- Restore periodic wildfire to fire-suppressed forest types

Conservation partners

- Sky Island Alliance

- Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project

- Southwest Center for Biological Diversity

Relationship to other classification schemes

This ecoregion corresponds to Omernik's ecoregion #23 (Arizona/New Mexico Mountains) and there is a considerable degree of overlap with Bailey's M313; Arizona-New Mexico Mountains Semi-Desert-Open Woodland-Coniferous Forest-Alpine Meadow Province.

See also

References

- B.D. Brand, A.B. Clarke and S. Semken. 2008. Eruptive conditions and depositional processes of Narbona Pass Maar volcano, Navajo volcanic field, Navajo Nation, New Mexico (USA).

- J.M. Hoekstra.; Molnar, J. L.; Jennings, M.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M. D.; Boucher, T. M.; Robertson, J. C.; Heibel, T. J. et al. 2010. Molnar, J. L., ed. The Atlas of Global Conservation: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities to Make a Difference. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26256-0.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Douglas-fir: Pseudotsuga menziesii, iGoTerra.com, ed. Nicklas Strõmberg

- John A. Murray. 1988. The Gila Wilderness. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

- Henry Smith Turner. 1966. Ed. Dwight L.Clarke. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma. The original journals of Henry Smith Turner with Stephen Watts Kearny to New Mexico and California, 1846-1847

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by, the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |