Tamaulipan mezquital

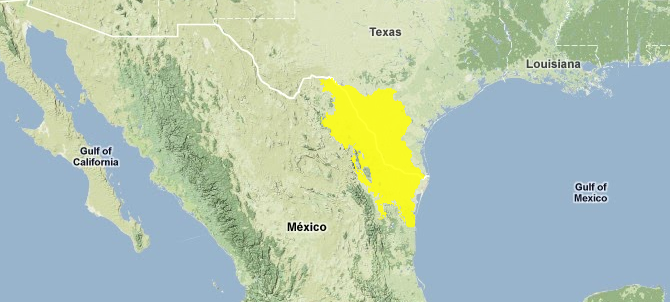

The Tamaulipan mezquital ecoregion, spanning southern Texas in the USA and northeastern Mexico, has unique plant and animal communities containing tree and brush covered dunes, windblown tidal flats, and dense native brushland.

Amistad Resevoir along Rio Grande, Texas, USA. Source: Laura Pierce Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Basin Coalition

Amistad Resevoir along Rio Grande, Texas, USA. Source: Laura Pierce Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Basin Coalition These communities contain such species as Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), Jaguarondi (Puma yagouaroundi), Reddish Egret (Egretta rufescens), the Texas Indigo Snake (Drymarchon corais erebennus), and over 400 disparate species of birds.

Location and General Description

The ecoregion is located on the physiographical province known as the Coastal Gulf Plain. It begins in the eastern part of the Coahuila State, in Mexico at the base of the Sierra Madre Oriental, and then proceeds eastward to encompass the northern half of the state of Tamaulipas, and into the United States through the south western side of Texas. Elevation increases northwesterly from sea level near the Gulf Coast to a base of about 300 meters (m) near the northern boundary of the ecoregion, from which a few hills or mountains protrude. The Anacacho Mountains and Turkey Mountain (550 m) in Kinney County, Texas, as well as Blue Mountain (389 m) in Uvalde Country, occur within this ecoregion.

The Rio Grande River flows through this Tamaulipan/Mezquital ecoregion and once formed a broad and meandering waterway that produced numerous resacas or oxbows within its floodplain, and an extensive marshy environment at its mouth. Some of the earliest Spanish explorers called the river Rio de las Palmas, because of the abundant palm trees that grew along its banks. These Texas palms once extended upriver as much as 80 miles, into this ecoregion. Today, the valley’s only remaining native palm grove is the 74 hectare (172 acres) Sabal Palm Grove Sanctuary.

The native vegetation type covering much of northeastern Mexico and parts of southern Texas is mesquite-grassland, an important element of the ecoregion that plant ecologists classify as characteristic of the Tamaulipan biotic province. The Tamaulipan province extends south of the border for almost 200 miles between the coast and the deciduous woodlands on the slopes of the Sierra Madre Oriental. The Tamaulipan thornscrub, a subtropical, semi-arid vegetation type, occurs on either side of the Rio Grande. Spiny shrubs and trees dominate this thornscrub, but grasses, forbs, and succulents are also prominent. The slightly higher, drier, and rockier sites originally had vegetation of chaparral and cacti, whereas the flat, deep soils supported mesquite as well as taller brush and a few drought-resistant trees, often rather openly spaced and savanna-like in a grassland matrix. This region also includes elements of pastizal, a combination of grassland, savanna, and páramo-like communities. Leguminous shrubs and trees constitute one-third of the diverse woody flora, which the rural population uses for extensive grazing of livestock, fuelwood, and timber for fencing and construction.

The two species that characterized the Mezquital communities before alteration were mesquite itself, Honey Mesquite (Prosopsis glandulosa), and the Curly Mesquite Grass (Hilaria belangeri) which was a common lower story associate. The most common shrubs were likely Lotebush (Zizyphus obtusifolia), which is often associated with limestone soils, and Whitebrush (Aloysia gratissima). Portions of this region consisted of open woods of mesquite, with a pronounced understory of grasses which often contained a layer of taller species such as Hooded Windmill Grass (Chloris cucullata), and a layer of shorter grasses such as Grama (Bouteloua spp). In some locales dense stands of Texas Prickly-pear (Opuntia engelmannii var. lindheimeri) would supplant many of the shrubs and grasses.

Montezuma Bald Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) was once common along the Rio Grande for 160 kilometers from the Gulf of Mexico. The tree is now rare along the Rio Grande, though it is still the dominant tree along the Rio Corona to the south. Perhaps the most striking endemic along the lower Rio Grande is the Texas Palmetto (Sabal mexicana), which was once common along resacas in the floodplain and held a dominant position over mesquite under certain conditions.

A few species of [[plant]s] account for the bulk of the brush vegetation of the Tamaulipan Mezquital and give it a characteristic appearance. The most significant of these taxa include: mesquite, various species of acacia including the Prickly Acacia (Acacia smallii) and Twisted Acacia (A. tortuosa), Spiny Hackberry (Celtis tala), Javelina Bush (Candalia ericoides), Texas Barometer Bush (Leucophyllum frutescens), Common Bee-brush or Whitebrush (Aloysia wrightii), Texas Prickly Pear, and Tasajillo or Desert Christmas Cactus (Opuntia leptocaulis). The only exceptions to the rather arid shrub-covered landscapes are the lines of riparian vegetation within the few river valleys.

Portions of this region support grasslands not unlike those of the Great Plains, though the grasslands here are not as uniform due to the highly variable soil and moisture conditions. The flora of the Tamaulipan Mezquital differs dramatically from the nearest desert, the Chihuahua desert, largely because of the Chihuahua’s higher elevations and generally colder winters. The number of species in the Tamaulipan Mezquital that are patently desert plants is notable, many taxa evincing affinities with the Sonoran Desert.

Biodiversity Features

The Tamaulipan Mezquital constitutes a unique assemblage of mesquite grassland in northeastern Mexico and the southern United States. The Sierra de San Carlos, at 1700 m above sea level, houses over 700 species of plants, eleven of which are endemic. The ecoregion contains at least two endemic genera of woody plants including the monotypic genus Clapdaisy (Clappia); and the genus Blackroot (Pterocaulon). It is also a rich zone in terms of endemic cacti, as well as the occurrence of endangered species. This ecoregion is also considered among the priority sites for conservation of succulents.

The southern part of the ecoregion is considered an Endemic Bird Area (EBA). Restricted-range species include the Red-crowned Amazon (Amazona viridigenalis), Crimson-collared Grosbeak (Rhodothraupis celaeno), Yellow-crowned Yellowthroat (Geothlypis flavovelata) and Tamaulipas Crow (Corvus imparatus). The southern nesting limits of two rare birds with very limited nesting ranges, the Black-capped Vireo (Vireo atricapillus) and Golden-cheeked Warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia) are restricted to northern Tamaulipan Mezquital, within Texas.

Some mammals of importance to this ecoregion are those that have been persecuted by humans for fear of their damage to livestock including the Mexican Prairie Dog (Cynomys mexicanus) one of the most endangered species of mammals in México. Also the larger cats including the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), which reaches its northern most limit in this ecoregion. Characteristic small mammals include Southern Plains Woodrat (Neotoma micropus), and Mexican Spiny Pocket Mouse (Liomys irroratus).

Anuran species found in this ecoregion are in part: the Red-spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus), who is found in rocky soils and open grasslands; the American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus), who favors warm shallow waters and is tolerant of certain water pollution; the Mexican Treefrog (Smilisca baudinii); the Mexican White-lipped Frog (Leptodactylus labialis); the Vulnerable Longfoot Chirping Frog (Eleutherodactylus longipes), who resides in forested areas or caves; the Spotted Chorus Frog (Pseudacris clarkii ), found typically near pond margins; the Rio Grande Chirping Frog (Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides), who is a sometimes fossorial anuran of lowland thickets; the Great Plains Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne olivacea), who inhabits arid mesquite lowlands; the Eastern Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus holbrookii), generally found east of the Edwards Plateau; Couch's Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchii), found in mesquite savanna and arid shrublands; the Mexican Burrowing Toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis), who is found in seasonally flooded savanna and thorn scrub. Salamanders in the ecoregion consist of two species: the Near Threatened Chunky False brook Salamander (Pseudoeurycea cephalica), a creature usually found under rocks, logs and other terrestrial debris; and the Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum), who prefers habitat with sandy or friable soil.

Current Status

Clearing and conversion of shrubland for agriculture has had the greatest impact on altering the patterns and processes of the landscape of south Texas and northeastern Mexico. Both banks of the Rio Grande are now crowded with homes, businesses, and farms. The only remaining natural areas south of the river are the salt marshes and mud flats east of the city of Matamoros. The Rio Corona floodplain was relatively intact until recently, but since the clearing of some lands for agriculture there has been increased erosion, pollution (Air pollution) from agrochemicals, invasion of exotic species (Alien species), and general loss of native wildlife. Only about two percent of this ecoregion remains as intact habitat, and most of the remaining area has been heavily altered by human activity. This ecoregion contains no habitat blocks larger than 250 [[kilometers] squared] (km2), and no protected areas. Only small patches of the original landscape remain. These remnants are largely isolated and provide little opportunity for species dispersal. The surrounding matrix, however, is composed of elements of the original landscape and some movement is possible.

Types and Severity of Threats

Conversion to agriculture poses the greatest threat to this ecoregion. Agricultural expansion and clearing for development may significantly alter more than a quarter of the remaining habitat over the next two decades. Degradation of habitat due to pollution (Air pollution) and exploitation of wildlife are significant but less pressing threats. In the valley of Jaumave, the land is commonly converted to cultivable fields by burning native vegetation. Cacti and other succulents are badly damaged or die during these processes. Most of the fires burn out of control, which adds a major threat to the plant communities of the ecoregion. Construction of dams, road building, mining and expansion of urban areas also cause habitat destruction. In addition, illegal extraction and trade of exotic plant species have endangered many species of cactus.

Further Reading

- Bailey, R.G. 1994. Ecological classification for the United States.

- Bibby, C.J., N.J. Collar, M.J. Crosby, M.F. Heath, Ch. Imboden, T.H. Johnson, A.J. Long, A.J. Stattersfield, and S.J. Thirgood. 1992. Putting Biodiversity on the Map: Priority Areas for Global Conservation. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge, U.K.

- Campbell, L. 1995. Endangered and threatened animals of Texas: Their life history and management. TPWD, Austin. ISBN: 9781885696045

- CONABIO Workshop, 17-16 September, 1996. Informe de Resultados del Taller de Ecoregionalización para la Conservación de México.

- CONABIO Workshop, Mexico, D.F., November 1997. Ecological and Biogeographical Regionalization of Mexico.

- Crosswhite, F. S. 1980. Dry country plants of the south Texas plains. Desert Plants 2(3):141-179.

- Howell, S.N.G. and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford Univ. Press, England. ISBN: 0198540124

- Jiménez-Guzmán, A., M. A. Zúñiga-Ramos, J.A. Niño-Ramírez. 1999. Mamíferos de Nuevo León, México. UANM, México.

- Martínez-Díaz, M. L. Hernández-Sandoval, and J. Martínez-Urbina. 1995. Inventario florístico de Sierra de San Carlos, Tamaulipas. XIII Congreso Mexicano de Botánica, Cuernavaca-Morelos del 5 al 11 de noviembre 1995. Libro de Resúmenes.

- Miller, B., G. Ceballos, and R. Reading. 1994. The prairie dog and biotic diversity. Conservation Biology 3: 677-681.

- Oldfield, S. (Comp). 1997. Cactus and Succulent Plants. Status survey and Conservation Action Plan.

- Omerinick, J.M. 1995. Ecoregions: A framework for managing ecosystems. George Wright Forum 12(1):35-51.

- Reid, N., J. Marroquín, and P. Beyer-Münzel. 1990. Utilization of shrubs and trees for browae, fuelwood, and timber in the Tamaulipan thornscrub, northeastern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 36: 61-79.

- Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de México. México: Editorial Limusa.

- Stattersfield, A.J., M.J. Crosby, A.J. Long and D.C. Wege. 1998. Endemic Bird Areas of the World: Priorities for Biodiversity Conservation. Birdlife Conservation Series No. 7, Cambridge, UK.

- Suzan, H. and G. Malda. 1990. Monitoreo demográfico en 5 cactáceas en peligro de extinción en Tamaulipas. Sociedad Botánica de México.

- U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge: Final environmental assessment.

| Disclaimer: This article contains certain information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |