Snake-Columbia shrub steppe

ContentsWWF Terrestrial Ecoregions Collection |

The Snake-Columbia shrub steppe is a vast, mostly arid ecoregion. Its easternmost limit is the Continental Divide in eastern Idaho. From there, the ecoregion follows the arc of the Snake River Plain as far as Hell's Canyon. The ecoregion thence extends throughout southeastern Oregon, spreading along the Deschutes River catchment to the Columbia River. It also includes, following hydrographic lines, parts of northern Nevada and the extreme northeast of California. To the north, the ecoregion dominates the western portion of the Columbia Basin in Washington. The Snake-Columbia shrub steppe is within the Nearctic Realm.

The ecoregion is largely in the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains and thus receives little precipitation. Latitude and physiography are influential factors in distinguishing this ecoregion from other similar ecoregions, such as the Wyoming Basin shrub steppe and Great Basin shrub steppe. The Snake-Columbia shrub steppe is lower in elevation than the Wyoming Basin, and the two catchments are separated by mountainous areas.

Biological distinctiveness

The Great Basin is hotter and drier than the Snake-Columbia, and lacks distinct major watersheds, exhibiting vegetation associations indicative of its proximity to true desert [[ecoregion]s] like the Mojave Desert. The ecoregion lacks the floristic diversity found in the Great Basin ecoregion. Situated as it is in a distinct major river system with consistent climatic and physiographic features, the Snake-Columbia ecoregion forms a logical unit, albeit disjunctive.

Fire, grazing, and variations in precipitation and temperature are the major disturbances in the ecoregion. Burning may encourage grass growth and impede sagebrush. Sagebrush, on the other hand, adapts to drought conditions that are unfavorable to grasses.

The Owyhee drainage (southwestern Idaho and southeastern Oregon) once supported salmon runs, making it one of the few high desert anadromous spawning areas.

Vegetation

The dominant vegetation in the ecoregion is sagebrush (Artemisia spp.), typically associated with various wheatgrasses (Agropyron spp.), Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) or other perennial bunchgrasses. The ecoregion contains a number of isolated mountain ranges in the southern parts of Idaho and Oregon, and here the sagebrush shrublands grade into bunchgrasses and juniper woodlands. Some parts of these ranges contain areas dominated by Douglas-fir (Psuedotsuga menziesii), Subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), and Aspen (Populus tremuloides). Riparian zones in the ecoregion typically contain cottonwoods (Populus spp.) and willows (Salix spp.). The ecoregion exhibits more desert-like vegetation in it southeastern Oregon reaches, where elevation is notably higher and precipitation at diminished levels. The same area, however, contains extensive wetlands, which provide vital waterfowl habitat in the Pacific Flyway.

Mammals

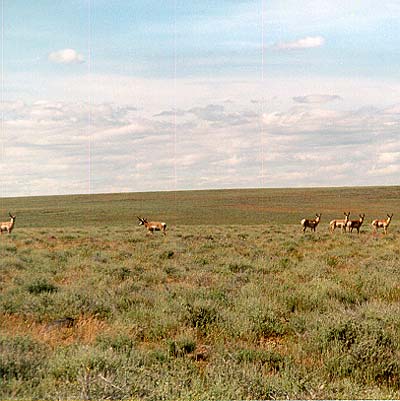

The ecoregion endemic Idaho ground squirrel. Source: Soheil Zendeh Example large mammals found in the Snake-Columbia ecoregion include Mountain lion (Puma concolor), Elk (Cervus elephus), Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) and Moose (Alces alces). Smaller mammals occurring in the ecoregion include the endemic and Endangered Idaho ground squirrel (Spermophilus brunneus); the Vulnerable endemic Townsend's ground squirrel (Spermophilus townsendii); the Near Threatened Washington ground squirrel (Spermophilus washingtoni); the Yellow bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris); and the Dark kangaroo mouse (Microdipodops megacephalus).

The ecoregion endemic Idaho ground squirrel. Source: Soheil Zendeh Example large mammals found in the Snake-Columbia ecoregion include Mountain lion (Puma concolor), Elk (Cervus elephus), Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) and Moose (Alces alces). Smaller mammals occurring in the ecoregion include the endemic and Endangered Idaho ground squirrel (Spermophilus brunneus); the Vulnerable endemic Townsend's ground squirrel (Spermophilus townsendii); the Near Threatened Washington ground squirrel (Spermophilus washingtoni); the Yellow bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris); and the Dark kangaroo mouse (Microdipodops megacephalus).

Birdlife

Numerous avifauna species are found in the ecoregion, including the Near Threatened Greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus); the Sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) and the Flammulated owl (Psiloscops flammeolus),

Reptiles

There are a number of reptilian species that are found in the ecoregion: the Rubber boa (Charina bottae); the Night snake (Hypsiglena torquata); the Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis); Western terrestrial garter snake (Thamnophis elegans); Longnose snake (Rhinocheilus lecontei); Yellow bellied racer (Coluber constrictor); Western rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis); Striped whipsnake (Masticophis taeniatus); Western gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer); Ringneck snake (Diadophis punctatus); Black-collared lizard (Crotaphytus insularis); Desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos); Pygmy short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglasii); the Endangered leopard lizard (Gambelia sila); Longnose leopard lizard (Gambelia wislizenii); Side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana); Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis); Sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus); Western whiptail (Cnemidophorus tigris); and Western pond turtle (Emys marmorata).

Amphibians

There are only a few amphibian taxa found in the ecoregion, namely: the Great Basin spadefoot (Spea intermontana); Woodhouse's toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii); the Boreal chorus frog (Pseudacris maculata); the Northern chorus frog (Pseudacris regila); the Northern leopard frog (Lithobates pipiens); the Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris); the Long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) and the Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum).

Conservation status

The Snake-Columbia shrub steppe ecoregion is given the ecocode NA1309 by the World Wildlife Fund. This ecoregion is classified within the Deserts and Xeric Shrublands biome.

Habitat loss and degradation

Greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Source: Lloyd Glenn Ingles, California Academy of Sciences & CalPhotos

Greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Source: Lloyd Glenn Ingles, California Academy of Sciences & CalPhotos Overgrazing by domestic livestock, overly aggressive fire suppression and resultant high-intensity blazes, and spread of exotic grasses are the major anthropogenic changes to the ecoregion. over the last 150 years. Diminution of native perennial grasses is a major problem in this ecoregion. Irrigation in the Washington and Idaho portions of the ecoregion have also incuced significant changes and have encouraged the spread of alien species. The loss of bluebunch wheatgrass (Agropyron spicatum) communities in the Owyhee Uplands portion of the ecoregion due to overgrazing in arid conditions.

Remaining intact habitat

Large intact areas, though degraded by overgrazing and exotic grass invasion, remain in southwestern Idaho, southeastern Oregon, and northwestern Nevada. Defense installations, such as the Yakima Firing Range and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, also protect extensive habitat areas in Washington.

Degree of fragmentation

Conversion of native habitat to agriculture, particularly in eastern Idaho and in Washington, are major sources of fragmentation. Exotic grass and noxious weed invasions (Alien species) are likewise becoming substantial enough to cause fragmentation.

Degree of protection

Federal defense installations, National Wildlife Refuges, National Monuments, and Wilderness Study Areas provide a fair degree of protection. However, without control of exotic grass and noxious weed invasions, protected areas may have a limited benefit in the longer term. Important protected areas include:

- Yakima Firing Range - southern central Washington

- Hanford Reservation - southern central Washington

- Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge - southern Oregon

- Malheur National Wildlife Refuge - southeastern central Oregon

- Craters of the Moon National Monument - southern Idaho

- Birch Creek Fen Preserve (TNC)

- Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge - northwestern Nevada

Ecological threats

Livestock grazing, invasion of alien plant taxa, irrigated agriculture, and recreation, especially through use of offroad vehicles, are the major threats to the ecological integrity of this ecoregion. Since there are no highly reliable methods for checking or reversing the tide of alien and noxious plant invasions, the spread of these species and consequent elimination of native plant communities is a significant threat. Combined with overgrazing and continued conversion to row crops, the ecoregion may be substantially altered and degraded in the near future.

Neighboring ecoregions

The following ecoregions have a common border with the Snake-Columbia shrub steppe:

- Great Basin shrub steppe, to the south

- Eastern Cascades forests, to the southwest

- Cascades Mountains leeward forests, to the northwest

- Okanagan dry forests, at the extreme north

- Palouse grasslands, at the northeast

- Blue Mountains forests, to the east and betwixt the two disjunctive units

- South Central Rockies forests, to the north and west of the southern disjunctive unit

Suite of priority activities to enhance biodiversity conservation

- Timely designation of wilderness study areas as actual wilderness areas is a high priority.

- If national defense installations continue to be phased out, it will be important to maintain these sites as protected areas, since a degree of ecological protection has been afforded by their use as military defense sites.

- Targeting specific sites and vegetation communities for protection from severe overgrazing will also be vital.

- Developing effective techniques for combating invasive species is a high priority as well.

- Restoration of salmon fisheries is an important ecological prospect that could have major implications for certain systems within the ecoregion.

- Substantial reductions in livestock grazing on public lands are urgently needed in order to combat threats of overgrazing.

Conservation partners

- Idaho Conservation League

- Oregon Wildlife Federation

- Oregon Natural Desert Association

- Oregon Natural Resources Council

References

- D.W.Meinig. 1968. The Great Columbia Plains: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910. University of Seattle Press, Seattle (Revised 1995). ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

- P.Morgan, S.C. Bunting, A.E. Black, T. Merrill, and S. Barrett. 1996. Fire regimes in the Interior Columbia River Basin: past and present. Final Report, RJVA-INT-94913. Intermountain Fire Sciences Laboratory, USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Missoula, Mont.

- R.F.Noss, E.T. LaRoe III, and J.M. Scott. 1995. Endangered ecosystems of the United States: a preliminary assessment of loss and degradation. U.S. National Biological Service. Biological Report 28.

Additional information on this ecoregion

- For a shorter summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

| Disclaimer: This article contains certain information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |