Shark Bay, Australia

| Topics: |

Geology (main)

|

Shark Bay (24°44'S-27°16'S, 112°49'E-114°17'E) is a World Heritage Site situated over 800 kilometers (km) north of Perth, on the westernmost point of the coast of Australia, Shark Bay is bounded by the town of Carnarvon to the north, and extends westwards to include the outer chain of Bernier, Dorre and Dirk Hartog islands, then over 200 km southwards joining up with Edel Land and extending southwards to Zuytdorp Nature Reserve. The western boundary is three nautical miles off the coast. The eastern boundary is adjacent to the coast south from Carnarvon to Hamelin Pool, then continuing southwards substantially inland from the west coast. The township of Denham and the areas around Useless Loop and Useless Inlet, although within the main boundary are specifically excluded from the World Heritage property.

Although chiefly known for its marine resources, the terrestrial elements of Shark Bay are also noted for their biodiversity, and the land area lies within the Carnarvon xeric shrublands ecoregion.

Contents

- 1 Date and History of Establishment

- 2 Area

- 3 Land Tenure

- 4 Altitude

- 5 Physical Features

- 6 Climate

- 7 Vegetation

- 8 Fauna

- 9 Cultural Heritage

- 10 Local Human Population

- 11 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 12 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 13 Conservation Value

- 14 Conservation Management

- 15 IUCN Management Category

- 16 Further Reading

Date and History of Establishment

The Shark Bay site was inscribed on the World Heritage List in the year 1991.

Area

Shark Bay, Australia. (Source: USC Sequence Stratigraphy Web)

Shark Bay, Australia. (Source: USC Sequence Stratigraphy Web) The extent of the Shark Bay area is 2,197,300 hectares (ha).Of this whole, protected areas, such as marine parks, marine nature reserves, terrestrial nature reserves and national parks, cover 1,004,000 ha. In addition, land in public ownership is divided into: pastoral land 450,000 ha; marine environment 687,750 ha; land in private ownership 750 ha; other reserves 2,500 ha; and vacant Crown Land 55,000 ha.

Existing conservation reserves include Friday Island (0.8 ha), Bernier and Dorre Islands (9,720 ha), Charlie Island (0.8 ha), Small Islands (205.58ha), Koks Island (2.6 ha), Zuytdorp Nature Reserve (58,850 ha), Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve (132,000 ha), Shark Bay Marine Park (748,725 ha), Francois Perou National Park (52,529 ha), Shell Beach Conservation Park (518 ha), and Monkey Mia Reserve (477 ha) in addition to Hamelin Pool/East Faure Island High-Low Water Mark (area undetermined).

Land Tenure

The state of Western Australia, the Government of Australia and private ownership.

Altitude

Sea level to 20 meters (m).

Physical Features

Shark Bay comprises a series of north-south facing peninsulas and islands which separate inlets and bays from each other and the Indian Ocean. The coastline is 1,500 km long and includes the 200 m high Zuytdorp cliffs, which are amongst the highest of the Australian coastline. There are three distinct landscape types: Gascoyne-Wooramel province which comprises the coastal strip along the eastern coast of the bay and consists of a low-lying plain backed by a limestone escarpment; Peron province which comprises the Nanga/Peron peninsulas; Faure Island/sill comprising undulating sandy plains with gypsum pans or birridas, and ancient interdune depressions filled with gypsum. The seaward margin of this province terminates in a scarp 3-30 m high and narrow sand beaches; Edel province which comprises Edel Land peninsula and Dirk Hartog, Bernier and Dorre Islands, is a landscape of elongated north-trending dunes cemented to loose limestone. The province terminates to the west as a series of spectacular cliffs.

The basement rock in the area is Late Cretaceous Toolonga limestone and chalk. The most extensive younger rocks are Peron sandstones and Tamala limestones (the offshore islands are composed of the latter). These rocks are often overlaid by a series of longitudinal fossil dunes accumulated during the Middle to Late Pleistocene. The extensive supratidal flats of Gladstone Embayment, Hutchison Embayment and Nilemah Embayment are comparable to the coastal 'Sabkhas' of the coast of the Arabian Gulf. Gypsum has been formed as a result of evaporation of saline groundwaters within the sediments of broad tidal flats adjacent to areas such as Hamelin Pool. Shell beaches occur at the southern end of Lharidon. The inland terrestrial landscape of Shark Bay is predominantly one of low rolling hills interspersed with birridas (inland saltpans that are at sea level). Shark Bay itself is a large shallow embayment, approximately 13,000 square kilometers (km2) in area, with an average depth of 9 m (maximum of 29 m). The bay is enclosed by a series of islands. Influx of oceanic water is through the wide northern channel, the Naturaliste channel, between Dorre and Dirk Hartog islands and South Passage between Dirk Hartog Island and Steep Point.

The outstanding feature of the bay is the steep gradient in salinities. The salinity gradient ranges from oceanic (salinity 35-40 parts per thousand (ppt)) in the northern and western parts of the bay through [[metahaline[[ (salinity 40-56 ppt) to hypersaline in Hamelin pool and Lharidon bight (salinity 456-470 ppt). The salinity gradient has created three biotic zones that have a marked influence on the distribution of marine organisms within the Bay. Tides vary with a spring range of 1.7m and a neap range of 0.6m. The Leeuwin current sweeps past Shark Bay, an intrusion of warm low-salinity tropical water of great zoological significance. The interaction of wind drift with tidal currents leads to a Bay circulation in which overall movement is anticlockwise from west to south-east, then east and finally north-west.

Two rivers drain into Shark Bay, including the intermittent flows of the Gascoyne and Wooramel River into the eastern part of the Bay. There is very little surface run-off because of the low rainfall, high evaporation and permeable soils. There is active regional saline groundwater flow, however, and some freshwater springs, such as in the intertidal zone north of Monkey Mia. There is a large quantity of artesian water approximately 300 m below the ground surface.

Climate

Shark Bay has a semi-arid to arid climate characterized by hot dry summers and mild winters. Summer temperatures average between 20 degrees Celsius (°C) and 35°C and winter temperatures between 10°C and 20°C. Average annual precipitation is low, ranging from 200 millimeters (mm) in the east to 400 mm in the far southwest. Annual high evaporation ranges from 2,000 mm in the west to 3,000 mm in the east.

Sea surface temperature outside the Bay varies from 20.9°C in August to 26°C in February. Within the Bay water temperatures vary; in the inner bay temperatures drop to 17°C in August. In February a maximum of 27°C has been recorded in Hamelin Pool, 26°C in Freycinet Reach and 24°C in the oceanic salinity zone. The Leeuwin Current flows along the West Australian [[coast]line] and greatly influences the temperature of seawater in the bay.

Vegetation

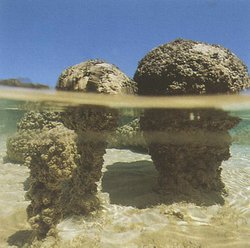

One of the most notable forms of vegetation in Shark Bay is the 'living fossil,' such as those shown here, in Hamelin Pool. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay)

One of the most notable forms of vegetation in Shark Bay is the 'living fossil,' such as those shown here, in Hamelin Pool. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay) The flora consists of a transition of the South-west Botanical Province to the Eremaean Botanical Province and more than 620 species have been recorded for the entire Shark Bay region, 145 at the northern limit of their range, 39 at their southern limit and 25 considered rare or threatened at the national level.

The South-west Botanical Province consists of vegetation that is rich in Eucalyptus species, forming woodland with diverse, shrubby understories and heathlands poor in grasses. The Eremaean province is correspondingly rich in Acacia species but has large areas dominated by grasses, especially prickly hummock grasses of the genera Triodia and Plectrachne. The Province includes shrublands of Acacia ligulata, Pimelea microcephala and Stylobasium spathulatum. Vegetation on the older dunes includes Melaleuca cardiophylla, Thryptomene baeckeacea and Plectrachne bromoides.

Mangroves occur in small, relatively isolated areas in southern and western Bay, only becoming abundant towards Carnarvon. The southernmost extensive stand of white mangrove Avicennia marina occurs on the Peron Peninsula. The marine flora is dominated by seagrass beds covering 4,000 km2. Twelve species of seagrass occur in the Bay: the most abundant species is Amphibolis antarctica, covering 90% of the seagrass bed area, providing a substratum for 66 species of algal epiphyte. Halodule seagrass beds occupy an area of approximately 500 km2.

Shark Bay is notable for benthic 'living fossil' microbial communities, forming an expansive and wide variety of microbial mats, which are best developed in Hamelin Pool, giving the area the most significant assembly of phototropic microbial ecosystems in the world. These photosynthetic prokaryotes and analogous eukaryotic microalgae, which commenced growing in the Pool when it first formed about 4000 years BP, trap and bind detrital sediment and thereby create organo-sedimentary microbialites or microbial mats, which have mineralized to form stromatolites in Hamelin Pool.

Fauna

The Shark Bay region is an area of major zoological importance, primarily due to the isolation of the marine and terrestrial ecosystems over significant periods of time. The Bay is located near the northern limit of a transition between temperate and tropical. For example, of the marine fish species 83% are tropical, 11% warm temperate and 6% cool temperate.

Of the 26 species of threatened Australian mammals, 5 are found on Bernier and Dorre islands; burrowing bettong Bettongia lesueur, rufous hare-wallaby Lagorchestes hirsutus, banded hare-wallaby L. fasciatus, Shark Bay mouse Pseudomys praeconis and western barred bandicoot Perameles bougainville. Greater stick-nest rat Leporilus conditor has recently been introduced on Salutation Island. In 1992, burrowing bettong was introduced on Heirisson Prong, and was followed with the release of Shark Bay mice in June 1994. Shark bay is renowned for its marine fauna, with 10,150 dugong Dugong dugon (V). Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae (V) and southern right whales use the bay as a migratory staging post. Bottle-nosed dolphin Tursiops truncatus can be seen at Monkey Mia. A minke whale was stranded on shore in 1981 and killer whales Orchinus orca were sighted attacking dugongs at Sandy Point in May 1983.

The rich avifauna includes over 230 species, with 11 breeding marine birds including osprey Pandion haliaetus and Caspian tern Sterna caspia, for which Failure Island is a key breeding area. Over 35 Asian migratory species occur in the region and four of these breed in Shark Bay. A number of birds reach their northern limit in the Bay including regent parrot Polytelis anthropeplus westralis and western yellow robin Eopsaltria australis griseogularis.

Shark Bay is noted for the diversity (Species diversity) of its herpetofauna, and supports nearly 100 species. It is rich in 'old Australian elements' with 12 species of diplodactyline geckos and 12 species of pygopodid lizards. Several characteristic species include leptodactylid Neobatrachus wilsmorei, hylid Cyclorani maini, gecko Diplodactylus squarrosus, skinks Egernia depressa, Lerista muelleri and Morethia butleri, and the monitors Varanus brevicauda, V. caudolineatus, V. eremius and V. giganteus. Green turtle Chelonia mydas (E) and loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (V) occur in the bay, nesting on the beaches at Dirk Hartog Island and Peron peninsula. The islands, peninsulas and gulfs provide a refuge for nine relict or endemic species: pygopodids Aclys concinna major, Aprasia haroldi and Pletholax gracilis edelensis, skinks Ctenotus youngsoni, C. zastictus, Egernia stokessi aethiops, Lerista maculosa and Menetia amaura. Shark Bay supports populations of at least six sea snake species including the endemic Aipysurus pooleorum.

Shark Bay is also an important nursery ground for crustaceans, fishes and coelenterates. The marine flora is dominated by seagrass beds providing a substratum for 100 species of zoophytes, juvenile fish and sea snakes. There are 323 fish species. Large numbers of sharks including bay whalers, tiger shark and hammerheads are readily observed in Shark Bay. There is also an abundant population of rays, including manta ray.

Because of the high organic productivity and development of seagrass beds and carbonate sand flats, the shallows of Shark Bay support a benthic invertebrate fauna of exceptional abundance, diversity and zoological significance. The invertebrate communities of Shark Bay remain essentially unstudied.

Coral reefs are present, although they are not abundant, with over 80 coral species. Hermatypic or reef building corals are found in South Passage and there are large patches along the east coast of Dirk Hartog, Bernier and Dorre Islands. The initiation of the Leeuwin current coincides with the mass spawning of hermatypic corals and is believed to be a major factor in the distribution and maintenance of coral communities in the region. In addition, of the 218 species of bivalve in the region, 75% have a tropical range, 10% a southern Australian range and 15% are west coast endemics.

Cultural Heritage

The record of aboriginal occupation of Shark Bay extends to 22,000 years BP. At that time most of the area was dry land, rising sea levels flooding Shark Bay between 8,000-6,000 years BP. A considerable number of aboriginal midden sites have been found, especially on Peron Peninsula and Dirk Hartog Island which provide evidence of some of the foods gathered from the waters and nearby land areas. The mild climate favored permanent residence.

Shark Bay was named by the English buccaneer William Dampier in the late 17th century. It is the site of the first recorded European landing in Western Australia, with the visit of Dirk Hartog in 1616, followed by William Dampier in 1699. The landing of Dirk Hartog on 25 October 1616 was commemorated by a pewter plate nailed to a post on the northern tip of Dirk Hartog Island, Cape Inscription. By virtue of its position, the area was a key navigation aid for navigators and explorers at this time. In 1712 the ship Zuytdorp of the Dutch East India Company was wrecked offshore and the French ships Uranie and Physicienne, commanded by Captain Freycinet, visited and studied Shark Bay in 1818. After 1850, the Shark Bay region was variously occupied by guano miners, pearlers, fishermen and pastoralists. Pearling was the biggest industry from 1850 until its decline in the 1940s to be replaced by fishing. The fishing industry peaked in the 1960s and has declined over the last two decades with the introduction of regulations introduced to prevent over-exploitation of fish stocks.

In 1904, until abandoned in 1911, quarantine hospitals were set up for aborigines with leprosy and venereal disease on Bernier and Dorre islands. After World War II, a whaling station was located at Carnarvon, and between 1950 and 1962 up to 7,852 humpback whales were killed. The station collapsed in 1963 due to a lack of whales.

Since the 1960s interaction of man and wild dolphin groups have occurred regularly in Monkey Mia on Shark Bay's Peron peninsula, the only known interaction on a regular basis in the world, a cultural heritage which parallels similar accounts from North Africa as described by Pliny the Younger in about 109 AD.

Local Human Population

Shark Bay has a population of approximately 750, principally located at Denham (population of 450) and Useless Loop. Some of the local residents are of aboriginal descent.

The economy of the region now includes tourism, fishing, and pastoralism. The residents of Carnarvon (located just outside of the bay area) are partially reliant on the fishing industry established in Shark Bay. The area is fished by 27 boats of the prawn fleet with a harvest reported to have stabilized at 2,000 tonnes over the last 20 years. Scallop fishery catches average at 3,500 tonnes per year from the 14 boats based at Carnarvon. The Shark Bay fisheries have a capital investment of approximately Australian $80 million, employing 500 people in the region. The fisheries harvest approximately Australian $35 million per year. In the 1960s salt evaporation works were established at Useless Loop, and a gypsum mine (now defunct) on Edel Land.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

Many visitor facilities have been installed in Shark Bay, such as this jetty and boat ramp in Monkey Mia. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay)

Many visitor facilities have been installed in Shark Bay, such as this jetty and boat ramp in Monkey Mia. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay) Tourism is important and more than 160,000 visitors per year are estimated to visit Shark Bay. The figure is increasing as a consequence of easier access with the construction of new roads, motels and hotels. One of the greatest tourist attractions of the region is sport fishing for which a number of fishing tours and charter vessels exist. Nearly all visitors (100,000 per year) come to see a group of wild bottle-nose dolphins which has been coming regularly to feed and interact with people at Monkey Mia beach for more than 30 years. In 1986 an information center was constructed at Monkey Mia in conjunction with the Shire of Shark Bay. The Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) has developed visitor facilities at Hamelin Pool, Shell Beach and Francois Peron National Park and provides a wide range of interpretive literature about the World Heritage Area.

Scientific Research and Facilities

Scientific specimens were first collected in 1699 by William Dampier on Dirk Hartog Island. In 1801, the naturalist Francois Peron, during the Baudin Expedition, made important observations on the marine fauna and made plant collections. Subsequently, the naturalists Quoy and Gaimard collected zoological specimens in Captain Freycinet's voyage to Shark Bay. Between 1818 and 1822 Phillip Parker King made the first comprehensive charts of the region for the Royal Navy. A summary of recent research in the Shark Bay area was produced in 1990 by the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee.

Conservation Value

The plaques on these rocks honor William Dampier, who first collected scientific specimens in Shark Bay in 1699. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay)

The plaques on these rocks honor William Dampier, who first collected scientific specimens in Shark Bay in 1699. (Source: Shire of Shark Bay) Shark Bay is a complete marine ecosystem containing many important features, including the Wooramel seagrass bank, the Faure sill and ecosystems dominated by benthic microbial communities which flourish in the hypersaline embayments, and living fossil stromatolites. Other features include a diversity of endemic and threatened plant and animal species and areas of great natural beauty.

Shark Bay contains the most diverse and abundant examples of prokaryotic stromolitic microbialites in the world, the world's best example of three-dimensional grazing stomatolites. The Hamelin pool occurrence of these microbial ecosystems offers the only extensive living analogue for comparable studies with Proterozoic stromatolites which yielded information of the nature, palaeoenvironment and evolution of the Earth's biosphere until the early Cambrian period. Modern examples including coccoid cyanobacterium which are thought to be descendants of a 1,900 million year old form, thus representing one of the longest continuing biological lineages known. The only other major microbialite occurrences in the world are in Lake Clifton in Western Australia and Lee Stocking Island in the Exuma cays of the Bahamas.

The hydrological structure of Shark Bay, altered by the Faure Sill, and a high evaporation rate has produced a basin which is one of the few areas in the world where marine waters are hypersaline, with salinities almost twice that of normal seawater. Shark Bay is one in the few marine areas of the world dominated by carbonates. The outstanding feature of the bay is the steep gradient in salinities which have created three biotic zones that have a marked effect on the distribution and abundance of marine organisms. With significant ongoing geological and biological processes in the marine environment, the steep saline gradients have produced genetic divergence within local populations, and so is an important area for genetic biodiversity such as the hypersaline conditions in Hamelin Pool leading to the development of unique microbialites and microbial mats.

Shark Bay contains the largest reported seagrass meadows in the world (4,000 km2) as well as some of the most species-rich seagrass]assemblages in the world. As such, these meadows are of international importance for their rich biodiversity and high organic productivity, supporting a benthic fauna of exceptional abundance. The Wooramel seagrass bank is the largest reported structure of its kind in the World, covering some 1,030 km2. The bank is one of the largest bodies of carbonate sediment formed by an organic baffle (stabilized carbonate sediment bound by seagrass beds) yet recorded from a modern environment. The only deposits of comparable origin and size are the seagrass beds on the Mediterranean coast of France.

Shark bay is of great botanical and zoological importance as the habitat of many species at the limit of their geographical range. It is the habitat for many species of plants and animals that are recorded as nationally and globally rare, vulnerable or threatened. Fifteen species of plant are considered to be rare or threatened at the national level. There are 26 globally threatened mammal species in Australia, Shark Bay has the only or major populations of five of these. Shark Bay contains approximately 12.5% of the world population of dugong, is a significant staging post for humpback whales and provides notable nesting sites for two species of endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) marine turtle. The only known 'lek' mating system in any marine mammal in the world is observable amongst South Cove dugong. The phenomenon of wild dolphins voluntary approaching humans is extremely uncommon worldwide; the only other similar long term interactions of wild dolphin and man are at Banc d'Arguin in Mauritania and another more recently established site in Brazil.

Conservation Management

The responsible administrative body is the Department of the Arts, Sports, the Environment, Tourism and Territories (DASETT), with its headquarters in Canberra. An agreement exists between the Government of Australia and the State of Western Australia on legislative and administrative arrangements for the management of Shark Bay. Collaborative bodies include the Department of Conservation and Land Management of the state of Western Australia. Day to day administration is undertaken by Western Australia primarily by the Department of Conservation and Land Management. It is in accordance with existing Western Australian legislation, including the Fisheries Act, Local Government Act, Land Act, Conservation and Land Management Act and the Environmental Protection Act.

In 1986 the Government of Western Australia resolved to prepare a planning strategy for Shark Bay, the Shark Bay Region Plan which is reported to simply favor the maintenance of the economic status quo. It was released for public comment in 1987 and finally adopted by the Western Australian government in June 1988. The Shark Bay Region Plan is currently being reviewed by the Western Australian Government. More detailed management plans are currently being prepared for all conservation reserves in the area. Draft management plans for the Shark Bay Marine Reserves, and the Monkey Mia Reserve were released in 1994 and 1993 respectively. A draft plan for the management of fish resources in the World Heritage Area was released in 1995. A strategic plan for the Shark Bay World Heritage Property is also in preparation. Any future, major changes to land-use would require further public consultation and Western Australian parliamentary approval. The region plan listed a total of 200,000 ha in existing protected areas in 1988. It identified further a proposed protected areas extension to 755,000 ha or 35% of Shark Bay. There are no aboriginal reserves in the Shark Bay area.

The Sustainable Future of Shark Bay report shows that environmental protection and appropriate local economic development (Patterns of economic growth and development) can be integrated into the area's management. It contains a broad management plan which if adopted, will enable conservation values to co-exist with fishing, tourism and the existing salt works. The disruption to the region's pastoral industry, it is reported, would be minimal. Offshore islands, including Bernier and Dorre islands are also nature reserves managed for conservation. The island reserves are recognized by restrictions on public access. The management of the trawl fishery includes restricting the number of boats, minimum mesh sizes, specifications and size of the fishing gear, setting up closed seasons and protection of the Shark Bay nursery areas. Damaging use of gill nets, which became serious in 1980-81, was effectively curbed by regulations introduced in 1981-82. The Western Australian Department of Fisheries has assessed commercial fishing pressure and undertaken extensive aerial survey programs and identified that commercial fishing in and around Shark Bay is relatively light. Insufficient information is available as to whether World Heritage nomination will lead to further restrictions of the local fishery as has been claimed by some sources.

In June 1990, the 105,352 ha Peron pastoral lease was purchased by the Government of Western Australia primarily for the purposes of conservation as outlined in the region plan. The northern part of the lease was gazetted as the Francois Peron National Park in 1993.

A feral animal control program is ongoing, and consideration is being given to extend control measures to prevent increases in populations. Successful control programs have been undertaken already, such as the eradication of goats from Bernier island.

In 1986 five full-time rangers were appointed to Monkey Mia dolphin area to prevent interference with dolphins and to undertake public awareness programs as a consequence of increased human pressure.

Management Constraints

The whole terrestrial section of the Shark Bay area has been partially modified due to the impact of pastoralism and other human activities. The pastoral leases exhibit localized areas of high disturbance around homesteads and stock watering points. A number of areas show evidence of past overgrazing by stock leading to soil erosion. The most disturbed areas were in the Tamala and Peron stations, where grazing and feral animals, particularly introduced rabbits and goats as well as predators such as fox and domestic cat, adversely affected the abundance of native animals, fire regimes have changed and grazing pressure is severe. Peron station has since been purchased by the Government, grazing terminated, major feral animal control program implemented, and the northern part of the station has been gazetted as a National Park.

The marine environment has undergone some modification as a result of the pearl shell industry, whaling and heavy fishing, the latter of which continues using bottom trawling, nets, lines and cray pots. In May 1990, a Greenpeace spokesman called for a ban on Shark Bay trawling and in July 1990 the executive director of the Australian Conservation Foundation is reported to have written to the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment stating that he had significant reservations about techniques used by the fishery; as a consequence fishermen are opposed to World Heritage listing. The fishing industry in the area totally refutes these allegations and states that fishermen harvest these resources at a sustainable level.

The township of Denham and the areas around Useless Loop and Useless Inlet are excluded from the nominated area although situated in the center of the zone. They could cause adverse impacts on the environment of the nominated area in the future. In particular, the Useless Loop evaporation salt works and the gypsum mine on Edel Land have been listed as potential threats. Tourism, such as boat activity along the inner coast of Dirk Hartog Island, may also pose a threat. There are risks of dugong, dolphin and marine turtle casualties from recreational boating. This is a much greater threat than the less than a dozen presumed dugong killed annually by local inhabitants of the region, for food. Insufficient staff has long been regarded as a hindrance. For long only one fisheries officer was available to patrol the entire region and proved entirely inadequate to prevent poaching.

Insufficient management controls have led to tourist pressure on the habituated population of wild dolphins at Monkey Mia. Tourism is still on the increase, resulting in the appointment of full-time rangers. In 1989 a dead calf and a further six dolphins were presumed to have been killed by pollution from a septic tank which has since been removed. The construction of a new road to Denham/Monkey Mia and the building of motels, hotels and caravan parks is dramatically increasing visitor numbers and seriously affecting the area. A draft management plan for Monkey Mia was released in 1993.

Staff

12.8 full time equivalents in the Department of Conservation and Land Management and 5.5 full time equivalents in the Department of Fisheries (1996).

Budget

Western Australian Department of Conservation and Land Management: approx. $800,000 (1995/96); Fisheries Department approx. $900,000 (1995/96).

IUCN Management Category

- Ia (Strict Nature Reserve)

- II (National Park)

- IV (Habitat/Species Management Area)

- Natural World Heritage Site - Criteria i, ii, iii, iv

Further Reading

- Anderson, P.K. (n.d.). Shark Bay: comments relevant to possible reserve status. Unpublished. 21 pp.

- Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds.). Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum, 312 pp. ISBN: 0730939197

- DASETT (1990). Nomination of Shark Bay, Western Australia by the Government of Australia for inclusion in the World Heritage List. Prepared by the Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories. Includes unseen film material.

- Davis, S.D., Droop, S.J.M., Gregerson, P., Henson, L., Leon, C.J., Lamlein Villa-Lobos, J., Synge, H., and Zantovska, J. (1986). Plants in danger, what do we know? IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 461 pp. ISBN: 2880327075

- Doak, W. (1989). The Monkey Mia Dolphins: a family affair. Encounters with Whales and Dolphins. Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney. Pp. 137-158.

- Edwards, H. (1988). The Monkey Mia Dolphins. In: Harrison, R. (Ed.) Whales, dolphins and porpoises. Merehurst Press, London. Pp. 208-213.

- Fox, R. (1991). The sea beyond the outback. National Geographic 179(1): 42-73.

- Humphries, R. (1991). Shark Bay. In: Habitat Australia. February 1990. Pp. 6-7.

- Hutchins, J.B. (1990). Fish Survey of South Passage Shark Bay, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 263-278.

- Jones, D.S. (1990). Annotated checklist of marine decapod Crustacea from Shark Bay, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 169-208.

- Keighery, G.J. (1990). Vegetation and flora of Shark Bay, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 61-88.

- Pryer, W. (1990). Green's Shark Bay stance draws fire. The West Australian. 7 December 1990. P. 28.

- Shark Bay Protection Group (1991). Why World Heritage listing for Shark Bay is opposed by local people and productive industry. Pamphlet.

- Slack-Smith, R.J. (1990). The bivalves of Shark Bay, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 129-158.

- Storr, G.M. (1990). Birds of the Shark Bay area, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 229-312.

- Storr, G.M. and Harold, G. (1990). Amphibians sand reptiles of the Shark Bay area, Western Australia. In: Berry, P.F., Bradshaw, S.D. and Wilson, B.R. (Eds), Research in Shark Bay. Report of the France-Australe Bicentenary Expedition Committee. Western Australia Museum. Pp. 279-286.

- WAFIC (1991). We share the sea, Shark Bay is fishing. Brochure by the Western Australian Fishing Industry Council, Western Australia.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |