Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal

| Topics: |

Contents

- 1 Geographical Location

- 2 Date and History of Establishment

- 3 Area

- 4 Land Tenure

- 5 Altittude

- 6 Physical Features

- 7 Climate

- 8 Vegetation

- 9 Fauna

- 10 Cultural Heritage

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 IUCN Management Category

- 17 Further Reading

Geographical Location

Sagarmatha National Park (27°45'-28°07'N, 86°28'-87°07'E) is a World Heritage Site which lies in the Solu-Khumbu District of the north-eastern region of Nepal. The park encompasses the upper catchment of the Dudh Kosi River system, which is fan-shaped and forms a distinct geographical unit enclosed on all sides by high mountain ranges. The northern boundary is defined by the main divide of the Great Himalayan Range, which follows the international border with the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China. In the south, the boundary extends almost as far as Monjo on the Dudh Kosi. The 63 settlements within the park are technically excluded as enclaves.

Date and History of Establishment

Created a national park on 19 July 1976 and inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1979.

Area

114,800 hectares (ha). The park lies adjacent to the proposed Makalu-Barun National Park and Conservation Area (233,000 ha).

Land Tenure

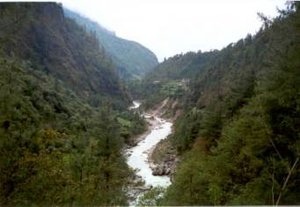

Khumbu Valley, Nepal. (Source: The University of Montana)

Khumbu Valley, Nepal. (Source: The University of Montana) State. Many of the resident Sherpas have legal title to houses, agricultural land and summer grazing lands.

Altittude

Ranges in altitude from 2,845 meters (m) at Jorsalle to 8,848 m, at the top of Mount Everest (Sagarmatha), the world's highest mountain.

Physical Features

This is a dramatic area of high, geologically young [[mountain]s] and glaciers. The deeply-incised valleys cut through sedimentary rocks and underlying granites to drain southwards into the Dudh Kosi and its tributaries, which form part of the Ganges River system. The upper catchments of these rivers are fed by glaciers at the head of four main valleys, Chhukhung, Khumbu, Gokyo and Nangpa La. Lakes occur in the upper reaches, notably in the Gokyo Valley, where a number are impounded by the lateral moraine of the Ngozumpa Glacier (at 20 kilometers (km) the longest glacier in the park). There are seven peaks over 7,000 m. The mountains have a granite core flanked by metamorphosed sediments and owe their dominating height to two consecutive phases of upthrust. The main uplift occurred during human history, some 500,000-800,000 years ago. Evidence indicates that the upliftis still continuing at a slower rate, but natural erosion processes counteract this to an unknown degree.

Climate

On average, 80% of the annual precipitation occurs in the monsoon season from June to September and the remainder of the year is fairly dry. Precipitation is low as the park is in the rain shadow of the Karyalung-Kangtega range to the south. Annual precipitation is 984 millimeters (mm) in Namche Bazar, 733 mm in Khumjung and 1043mm in Tengboche. The climate of Namche Bazar can be classified as humid and tropical, based on the seasonal occurrence of rains, range in annual precipitation, number of rainy days per year and the length of the dry season. The mean temperature of the coldest month, January, is -0.4°C. Some 56% of years experience a tropical regime (summer rain), 35% are bixeric (two dry periods) and 1% are trixeric (three dry periods) or irregular.

Vegetation

Most of the park (69%) comprises barren land above 5,000 m, 28% is grazing land and nearly 3% is forested. Six of the 11 vegetation zones described by Dobremez for the Nepal Himalaya are represented in the park: lower subalpine, above 3,000 m, with forests of blue pine Pinus wallichiana, fir Abies spectabilis and fir-juniper Juniperus recurva; upper subalpine, above 3,600 m, with birch-rhododendron forest (Betula utilis, Rhododendron campanulatum and R. campylocarpum); lower alpine, above the timber-line at 3,800-4,000 m, with scrub (Juniperus spp., Rhododendron anthopogon and R. lepidotum); upper alpine, above 4,500 m, with grassland and dwarf shrubs; and sub-nival zone with cushion plants from 5,500 m to 6,000 m. Oak Quercus semecarpifolia used to be the dominant species in the upper montane zone but former stands of this species and Abies spectabilis have been colonised by Pinus sp. Rhododendron arboreum, R. triflorum, and yew Taxus baccata wallichiana are associated with pine at lower altitudes and shrubs include Pieris formosa, Cotoneaster microphyllus and R. lepidotum. Vine Parthenocissus himalayana and clematis Clematis montana are also common and other low altitude trees include maple Acer campbellii and whitebeam Sorbus cuspidata. Abies spectabilis occupies medium to good sites above 3,000 m and forms stands with Rhododendron campanulatum or Betula utilis. Towards the tree line, R. campanulatum is generally dominant. Juniperus indica occurs above 4,000 m, where conditions are drier, along with dwarf rhododendrons and cotoneasters, shrubby cinquefoil Potentilla fruticosa var. rigida, willow Salix sikkimensis and Cassiope fastigiata. In association with the shrub complex are a variety of herbs such as Gentiana prolata, G. stellata, edelweiss Leontopodium stracheyi, Codonopsis thalictrifolia, Thalictrum chelidonii, lilies Lilium nepalense and Notholirion macrophyllum, Fritillaria cirrhosa and primroses, Primula denticulata, P. atrodentata, P. wollastonii and P. sikkimensis. The shrub layer diminishes as conditions become cooler and above 5,000 m Rhododendron nivale is the sole representative of its genus. Other dwarf shrubs in the dry valley uplands include buckthorn Hippophae tibetana, horsetail Ephedra gerardiana, juniper J. indica and cinquefoil Potentilla fruticosa. Associated herbs are gentians, Gentiana ornata and G. algida var. przewalskii, edelweiss Leontopodium jacotianum and Himalayan blue poppy Meconopsis horridula. Above this and up to the permanent snow line at about 5,750 m, plant life is restricted to lichens, mosses, dwarf grasses and sedges and alpines, such as Arenaria polytrichoides and Tanacetum gossypinum.

Fauna

Himalayan tahr Hemitragus jemlahicus. (Source: Stephen Sumithran)

Himalayan tahr Hemitragus jemlahicus. (Source: Stephen Sumithran) In common with the rest of the Nepal Himalaya, the park has a comparatively low number (28) of mammalian species, apparently due to the geologically recent origin of the Himalaya and other evolutionary factors. The low density of mammal populations is almost certainly the result of human activities. Larger mammals include common langur Presbytis entellus, jackal Canis aureus, a small number of grey wolf Canis lupus (V), Himalayan black bear Selenarctos thibetanus (V), lesser panda Ailurus fulgens (V), yellow-throated marten Martes flavigula, Himalayan weasel Mustela sibirica, masked palm civet Paguma larvata, snow leopard Panthera uncia (E), Himalayan musk deer Moschus chrysogaster, Indian muntjac Muntiacus muntjak, mainland serow Capricornis sumatraensis (I), Himalayan tahr Hemitragus jemlahicus (K) and goral Nemorhaedus goral. Sambar Cervus unicolor has also been recorded. The tahr population is estimated to total at least 300 individuals. Both goral and serow appear to be uncommon. Results from recent surveys suggest that populations of both tahr and musk deer have increased substantially since the park was gazetted and could lead to a recovery in the snow leopard population, probable signs of which were seen in the Gokyo Valley. Smaller mammals include short-tailed mole Talpa micrura, Tibetan water shrew Nectogale elegans, Himalayan water shrew Chimarrogale himalayica, bobak marmot Marmota bobak, Royle's pika Ochotona roylei, woolly hare Lepus oiostolus, rat Rattus sp. and house mouse Mus musculus.

Additionally, there are 152 species of birds, 36 of which are breeding species for which Nepal may hold internationally significant populations. The park is important for a number of species breeding at high altitudes, such as blood pheasant Ithaginis cruentus, robin accentor Prunella rubeculoides, white-throated redstart Phoenicurus schisticeps, grandala Grandala coelicolor and several rosefinches. The park's small lakes, especially those at Gokyo, are used as staging points for migrants and at least 19 water bird species have been recorded.

A total of six amphibians and seven reptiles occur or probably occur in the park. Documentation of the invertebrate fauna is limited to common species of butterfly. Of the 30 species recorded, orange and silver mountain hopper Carterocephalus avanti has not been recorded elsewhere in Nepal, and the common red apollo Parnassius epaphus is rare.

Cultural Heritage

The Sherpas are of great cultural interest, having originated from Salmo Gang in the eastern Tibetan province of Kham, some 2,000 km from their present homeland. They probably left their original home in the late 1400s or early 1500s, to escape political and military pressures, and later crossed the Nangpa La into Nepal in the early 1530s. They separated into two groups, some settling in Khumbu and others proceeding to Solu. The two clans (Minyagpa and Thimmi) remaining in Khumbu are divided into 12 subclans. The introduction of the potato to Khumbu in about 1850 revolutionized the economic life of the Sherpas. Until then, the high-altitude Sherpas had lived mainly on barley. Both the population and the growth of the monasteries took a dramatic upturn soon after that time. Another significant influence on Sherpa life has been mountaineering expeditions, which have been a feature of life in the Khumbu since the area was first opened to westerners in 1950. The Sherpas belong to the Nyingmapa sect of Tibetan Buddhism, which was founded by the revered Guru Rimpoche who was legendarily born of a lotus in the middle of a lake. It is to him that the ever-present prayers and mani wall inscriptions are addressed: "Om mani padme hum" - "hail to the jewel of the lotus." There are several monasteries in the park, the most important being Tengpoche. However, on 19 January 1989 the main building and courtyard of Tengpoche was burned to the ground. A Reconstruction Committee has been formed and it is planned to commence reconstruction work in 1990.

Local Human Population

There were an estimated 3,500 Sherpas residing in the park in 1997, mainly in the south and distributed among 63 settlements. However, there has not been an accurate census since the park was established. The traditional economy is subsistence agro-pastoralism, supplemented by barter trading with Tibet and the middle hills of Nepal. The main activities include potato and buckwheat cultivation, and raising yaks for wool, meat, manure and transport. Cattle and yaks are also hybridized locally for trading purposes. Cattle numbers remained constant at about 2,900 between 1957 and 1978 but the numbers of sheep and goats increased from very few to 641. Goats have since been removed from the park. There are also reports which indicate that the local economy has more recently become dependent upon tourism, with activities such as provision of guides, porters, lodges and trekking services providing employment.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

Mt Everest, the world's highest mountain. (Source: DePaul University)

Mt Everest, the world's highest mountain. (Source: DePaul University) The number of visitors has increased from about 1,400 in 1972/1973 to 7,492 in 1989. There is an airstrip at Lukla, south of the park boundary, which has a regular air service from Kathmandu, and is the most popular means of access to the park. Everest View Hotel and associated Shyangboche airstrip above Namche Bazar are the most sophisticated tourist facilities developed in the park but they do not account for a high proportion of visitor use. A national park lodge has been built at Tengpoche providing sleeping accommodation, with detached cooking and toilet facilities, as well as basic food and drinks. Other accommodation is available in 'Sherpa hotels' and some villagers take in guests. An imposing visitor center, providing information and interpretative services, has been constructed on the hill adjoining Namche Bazar. Further facilities, by way of park accommodation and campsites, are planned. A handbook has been produced for the park.

Scientific Research and Facilities

Considerable research in various fields has been undertaken over many years. The Sherpa culture and changes that have taken place over the last decade or more have been extensively documented. Under the HMG/Government of New Zealand Cooperation Project, the impact of pastoralism and tourism on the natural resource base has been assessed. Research into alternative sources of energy has focused on hydropower, solar heating and developing more efficient methods of cooking. A World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-funded study of the ecology of Himalayan musk deer has been carried out in the park. A proposal has been made for forest research and management, focused primarily on protection of representative samples of ecosystems, reforestation and introduction of alternative energy sources to minimize human impact (Land-use and land-cover change) on natural forests.

Conservation Value

Sagarmatha ('Mother of the Universe'), as the highest point of the Earth's surface, and its surroundings are of international importance, representing a major stage of the Earth's evolutionary history and one of the most geologically interesting [[region]s] in the world. Its scenic and wilderness values are outstanding. As an ecological unit, the Dudh Kosi catchment is of biological and socio-economic importance, as well as being of major cultural and religious significance.

Conservation Management

Creation of a national park in the Sagarmatha area was proposed by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) Wildlife Management Adviser in March 1971 and approved in principle by His Majesty's Government in January 1972. Funds for its development were made available by the Government of New Zealand over a five year period, commencing in May 1975. Normally accepted criteria for management of national parks have been substantially modified in the case of Sagarmatha in order to reconcile the requirements of the resident Sherpa population with those of conservation objectives and to accommodate special demands made on the area by tourism and mountaineering. Objectives outlined in the management plan seek to ensure the protection of wildlife, water (Water resources) and soil resources, not only because of the park's national and international significance but also to safeguard the interests of the resident Sherpa population, as well as the many other people in Nepal and India whose welfare is affected by the condition of the Dudh Kosi catchment. At the same time, every effort is required to enable the Sherpas to determine their own lifestyle and progress, while insulating their cultural and religious heritage from the adverse impacts of tourism and mountaineering. Park regulations do not apply to the 63 settlements within the park.

Two strict nature protection areas have been identified in the south of the park, to be managed as undisturbed areas free from human interference. Laws are enforced with military assistance. An integrated strategy for achieving self-sufficiency in resources and nature conservation has been developed. Various recommendations are being implemented. A Park Advisory Committee, consisting of local leaders, village elders, head lamas and park authority representatives, was re-established in 1987 and has been instrumental in achieving more cooperation and support for the park. The importance of tourism in the local economy has also encouraged Sherpas to assist in protecting the area. The Shinga nawa - a system of forest guardians traditionally responsible for controlling use of forest resources - has been reinstated. Duties of the nawas include prevention of greenwood cutting, protection of plantations and reporting of wildlife poaching. Nawas are authorised to prosecute and collect limited penalties from violators of the forest protection rules, and to use the fines for community purposes. Indigenous plant nurseries have been established at Namche Bazar and Trashinga: seedlings are used to re-establish forest on hill slopes near Namche Bazar, Phortse and Khumjung.

The Himalayan Trust, established by Sir Edmund Hillary, has sponsored several school, hospital and bridge construction projects. In 1982 the Trust purchased and removed the 400 goats in the park in an effort to protect the mountain vegetation. Goats were banned from the park the following year. Several steps have been taken to help meet the energy needs of increasing numbers of tourists, including regulations regarding firewood collection, reforestation and increased use of kerosene. The Namche Hydroelectric scheme provides 27 kilowatts (kW) of electricity to local houses and lodges, and has proven to be cost effective and useful in reducing firewood scarcity.

Management Constraints

The loss of forest cover in the region began some 500 years ago, with the arrival of the first settlers. Destruction rapidly accelerated following the influx of Tibetan refugees during 1959-1961 and the large-scale growth of trekking and mountaineering from 1963 onwards. Increased affluence from tourism has also resulted in greater ecological degradation. In line with the custom of many ethnic Nepalese groups, acquired wealth in a Sherpa family is generally invested in additional livestock which consequently leads to overgrazing of high mountain pastures around villages. Heavy pressure from tourism and mountaineering expeditions has placed large demands on natural resources and introduced problems with waste disposal. Demand for construction timber and firewood, another result of visitor pressure, has impoverished the forests to an alarming degree; consequent soil erosion has made reforestation difficult, pastures at lower altitudes are being overgrazed and water is becoming unfit for drinking. An assessment (Environmental Impact Assessment) of landscape change (Land-use and land-cover change) using repeat photography, however, indicates that most forests in the Namche-Kunde-Khumjung region appear to be relatively unchanged, although juniper woodlands have been thinned in the period 1962-1984. Attempts are being made to encourage Sherpas and military personnel to use paraffin (kerosene) for fuel rather than wood, but lack of funds for purchasing the paraffin has so far prevented this. Diminishing habitat is adversely affecting some species of wildlife. The traditional culture of the Sherpas is being changed due to foreign influences, but perhaps with better social integrity than nearly any other tribal group known to the modern world. Limited poaching of musk deer persists.

Staff

One chief warden, two assistant wardens, one veterinary surgeon, seven rangers, seven senior game scouts, 25 game scouts and 14 office staff (1989). One company of the Royal Nepal Army is deployed for protection purposes.

Budget

In 1989/1990 expenditure was NRs 2,003,800 (US$ 66,793) and income NRs 2,262,050 (US$ 75,402). The budget for 1990/1991 is NRs 1,982,000 (US$ 66,067).

IUCN Management Category

- II (National Park)

- Natural World Heritage Site - Criterion iii

Further Reading

The World Heritage nomination includes an extensive bibliography.

- Bishop, B.C. (1988). A fragile heritage: the mighty Himalaya. National Geographic 174: 624-631.

- Blower, J.H. (1972). Establishment of Khumbu National Park: outline project proposal. HMG/UNDP/FAO Project NEP/72/002, Kathmandu. Unpublished report.

- Bjonness, I.M. (1979). Impacts on a high mountain ecosystem: recommendations for action in Sagarmatha (Mount Everest) National Park. Unpublished Report. 38 pp.

- Bjonness, I.M. (1980a). Animal husbandry and grazing, a conservation and management problem in Sagarmatha National Park. Norsk Geogr. Tidskr. 33: 59-76.

- Bjonness, I.M. (1980b). Ecological conflicts and economic dependency on tourist trekking in Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal. An alternative approach to park planning. Norsk Geogr. Tidskr. 34: 119-138.

- Bjonness, I.M. (1983). External economic dependency and changing human adjustment to marginal environment in the high Himalaya, Nepal. Mountain Research and Development 3: 263-272.

- Brook, E. (1988). Through Sherpa eyes. Geographical Magazine 60(8): 28-34.

- Byers, A. (1987). An assessment of landscape change in the Khumbu region of Nepal using repeat photography. Mountain Research and Development 7: 77-81.

- Coburn, B. (1982). Alternate energy sources for Sagarmatha National Park. Park techniques. Parks 7(1): 16-18.

- Coburn, B.A. (1983). Managing a Himalayan world heritage site. Nature and Resources 19(3): 20-25.

- Coburn, B.A. (1985). Energy alternatives for Sagarmatha National Park. In: People and protected areas in the Hindu Kush-Himalaya. King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation/International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu. Pp. 71-72.

- Dobremez, J.F. (1975). Le Nepal, écologique et phytogéomorphique. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris.

- Dobremez, J.F. and Jest, C. (1972). Carte écologique du Nepal. Région Kathmandu-Everest 1/250,000. Documents de Cartographie Ecologique, Grenoble.

- FAO (1980). National parks and wildlife conservation, Nepal: project findings and recommendations. UNDP/FAO Terminal Report, Rome. 63 pp.

- Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von (1964). The Sherpas of Nepal. John Murray, London. 298 pp.

- Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von (1975). Himalayan traders. John Murray, London. 316 pp. ISBN: 0719531799.

- Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von (1985). The Sherpas transformed. Sterling, New Delhi. 197 pp. (Unseen)

- Garratt, K.J. (1981). Sagarmatha National Park management plan. HMG/New Zealand Co-operation Project. Department of Lands and Survey, New Zealand.

- Hinrichsen, D., Lucas, P.H.C., Coburn, B. and Upreti, B.N. (1983). Saving Sagarmatha. Ambio 12: 203-205.

- Inskipp, C. (1989). Nepal's forest birds: their status and conservation. International Council for Bird Preservation Monograph No. 4. 160 pp.

- Jackson, R. and Ahlborn, G. (1987). Snow Leopard surveys in Nepal. Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park. Cat News 7: 24-25.

- Jefferies, B.E. (1982). Sagarmatha National Park: the impact of tourism in the Himalayas. Ambio 11: 274-281.

- Jefferies, B.E. (1984). The Sherpas of Sagarmatha. In: McNeely, J.A. and Miller, K., National Parks, conservation and development. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC. Pp. 473-478. ISBN: 0874746639.

- Jeffries, M. and Clarbrough, M. (1986). Sagarmatha: mother of the universe. The story of Mount Everest National Park. Cobb/Horward Publications, Auckland, New Zealand. 192 pp.

- Joshi, D.P. (1982). The climate of Namche Bazar: a bioclimatic analysis. Mountain Research and Development 2: 399-403.

- Kattel, B. (1987). Himalayan musk deer ecology project, Nepal. Annual Report. King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation/WWF-US Project No. 6076. 10 pp.

- Kohl, L. (1988). Heavy hands on the land. National Geographic 174: 633-651.

- Lovari, S. (1990). Some notes on the wild ungulates of the Sagarmatha National Park, Khumbu Himal (Nepal). Caprinae News 5(1): 2-4.

- Lucas, P.H.C. (1977). Nepal's park for the highest mountain. Parks 2(3): 1-4.

- Luhan, M. (1989). Following the toilet paper trail. Himal 2(2): 18-19.

- Milne, R.C. (1997) Mission Report: South Asia meeting to review status conservation of world natural heritage and design and cooperative plan of action. 16-19 January 1997, New Delhi, India. Prepared for the World Heritage Centre, UNESCO. Unpublished Report, 7pp.

- Sassoon, D. (1989). The Tengboche fire: what went up in flames. Himalayan Research Bulletin 8(3): 8-14.

- Sherpa, M.N. (1985). Conservation for survival: a conservation strategy for resource self-sufficiency in the Khumbu region of Nepal. M.Sc. dissertation, Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba, Canada. 175 pp.

- Sherpa, L.N. (1987). A proposal for forest research and management in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Nepal. Working Paper No. 8. East-West Center, Hawaii. 47 pp.

- Smith, C. (in press). Commoner butterflies of Sagarmatha National Park. In: National Park Handbook.

MAPS

- 1:100,000 Mount Everest Region. Royal Geographical Society, London, 1975.

- 1:50,000 Mount Everest. National Geographic Society, Washington DC, 1988.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |