Molybdenum

Molybdenum is a metallic, silvery-white element, with an atomic number of 42. Its chemical symbol is Mo. Chemically, it is very stable, but it will react with acids. The physical characteristic that makes molybdenum unique is that it has a very high melting point at 4,730 degrees Fahrenheit. This is 2000 degrees higher than the melting point of steel. It is 1,000 degrees higher than the melting temperature of most rocks. It has the fifth highest melting point of all of the elements.

Molybdenite (MoS2, molybdenum sulfide) is the major ore mineral for molybdenum (sometimes called moly for short). It is rarely found as crystals, but is commonly found as what mineralogists describe as foliated masses. This means the mineral forms folia or layers, like the mineral mica. It is metallic gray, has a greasy feel, and is very soft at only 1 on Mohs' hardness scale. Its softness, metallic luster and gray color led scientists to mistakenly believe it was a lead mineral. Geologically, molybdenite forms in high-temperature environments such as in igneous rocks. Some molybdenite forms when igneous bodies contact rock and metamorphose, or change, the rock. This is called contact metamorphism.

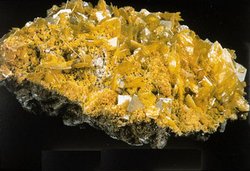

Molybdenum is also found in the mineral wulfenite (Pb(MoO4), lead molybdate). Wulfenite forms colorful, bright orange, red, and yellow crystals. They can be blocky or so thin that they are transparent.

Molybdenum is a needed element in plants and animals. In plants, for example, the presence of molybdenum in certain enzymes allows the plant to absorb nitrogen. Soil that has no molybdenum at all cannot support plant life.

Molybdenum was discovered by the Swedish scientist, Peter Hjelm in 1781, three years after Carl Scheele proposed that a previously unknown element could be found in the mineral molybdenite.

Contents

Name

| Previous Element: Niobium Next Element: Technetium |

| |

| Physical Properties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Color | silvery-white | |

| Phase at Room Temp. | solid | |

| Density (g/cm3) | 10.28 | |

| Hardness (Mohs) | --- | |

|

Melting Point (K) |

2890.2 | |

|

Boiling Point (K) |

4923 | |

| Heat of Fusion (kJ/mol) | 27.6 | |

| Heat of Vaporization (kJ/mol) | 590 | |

| Heat of Atomization (kJ/mol) | 658 | |

| Thermal Conductivity (J/m sec K) | 138 | |

| Electrical Conductivity (1/mohm cm) | 192.308 | |

| Source | Molybdenite (sulfide) | |

| Atomic Properties | ||

| Electron Configuration | [Kr]5s14d5 | |

|

Number of Isotopes |

36 (7 natural) | |

| Electron Affinity (kJ/mol) | 72 | |

| First Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) | 684.9 | |

| Second Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) | 1588.2 | |

| Third Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) | 2620.5 | |

| Electronegativity | 2.24 | |

| Polarizability (Å3) | 12.8 | |

| Atomic Weight | 95.94 | |

| Atomic Volume (cm3/mol) | 9.3 | |

| Ionic Radius2- (pm) | --- | |

| Ionic Radius1- (pm) | --- | |

| Atomic Radius (pm) | 139 | |

| Ionic Radius1+ (pm) | --- | |

| Ionic Radius2+ (pm) | --- | |

| Ionic Radius3+ (pm) | 83 | |

| Common Oxidation Numbers | +4, +6 | |

| Other Oxid. Numbers | -2, -1, +1, +2, +3, +5 | |

| Abundance | ||

| In Earth's Crust (mg/kg) | 1.2x100 | |

| In Earth's Ocean (mg/L) | 1.0x10-2 | |

| In Human Body (%) | 0.000007% | |

| Regulatory / Health | ||

| CAS Number | 7439-98-7 | |

| OSHA Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) | TWA: 15 mg/m3 | |

| OSHA PEL Vacated 1989 | TWA: 10 mg/m3 | |

|

NIOSH Recommended Exposure Limit (REL) |

IDLH: 5000 mg/m3 | |

|

Sources: |

||

In 1778, Swedish chemist Carl William Scheele was studying, what he thought was lead, in the mineral molybdenite. Molybdenite was named after the Greek word molybdos, which means lead. Sheele's studies led him to the conclusion that this mineral did not contain lead, but some other element. He named this new element molybdenum after the mineral molybdenite. (As an aside, the mineral scheelite (Ca(WO4,MoO4), calcium tungstate-molybdate) was named after Scheele in honor of his discovery of molybdenum.)

In biology

The majority of molybdenum molecules or salts have low aqueous solubility, but the molybdate ion MoO42− is somewhat soluble and will form if molybdenum-containing minerals are in contact with oxygen and water. Recent theories suggest that oxygen respiration (release) by early lifeforms was important in removing molybdenum from minerals into a soluble form in the early oceans, where it was used as a catalyst by single-celled organisms. This chain of events may have been key in the history of life, because molybdenum-containing enzymes then became significant cellular catalysts employed by certain bacteria to break molecular nitrogen, permitting biological nitrogen fixation. This, in turn allowed biologically driven nitrogen-fertilization of the oceans, and thus the development of more complex organisms.

More than fifty molybdenum-containing enzymes have been identified in bacteria and animals, even though only the bacterial and cyanobacterial enzymes are involved in nitrogen fixation. Due to the diverse functions of some of the molybdenum enzymes, molybdenum is an essential trace nutrient for life in higher organisms, but not in all bacteria.

Sources

The most important ore source of molybdenum is the mineral molybdenite. A minor amount is recovered from the mineral wulfenite. Some molybdenum is also recovered as a by-product or co-product from copper mining.

The United States produces significant quantities of molybdenite from mines in Colorado, New Mexico, and Idaho. Other mines in Arizona, New Mexico, Montana, and Utah produce molybdenum as a by-product. The largest molybdenum resource in the U.S. is in Climax, Colorado. It is estimated that there are 5.5 million metric tons of molybdenum in the United States. It is probable there are more molybdenum resources in the U.S. yet to be discovered.

There are significant molybdenum resources around the world. The leading producers are Canada, China, Chile, Mexico, Peru, Russia and Mongolia. It is estimated that there are 12 million metric tons of molybdenum in the world. Other ore deposits may be discovered in the future.

Uses

Molybdenum is alloyed with steel making it stronger and more highly resistant to heat because molybdenum has such a high melting temperature. The alloys are used to make such things as rifle barrels and filaments for light bulbs. The iron and steel industries account for more than 75% of molybdenum consumption.

The two largest uses of molybdenum are as an alloy in stainless steels and in alloy steels-these two uses consume about 60% of the molybdenum needs in the United States. Stainless steels have the strength and corrosion-resistant requirements for water distribution systems, food handling equipment, chemical processing equipment, home, hospital, and laboratory requirements. Alloy steels include the stronger and tougher steels needed to make automotive parts, construction equipment, and gas transmission pipes.

Other major uses as an alloy include: Tool steels, for things like bearings, dies, and machining components; cast irons, for steel mill rolls, auto parts, and crusher parts; super alloys for use in furnace parts, gas turbine parts, and chemical processing equipment.

Molybdenum also is an important material for the chemicals and lubricant industries. Molybdenum has uses as catalysts, paint pigments, corrosion inhibitors, smoke and flame retardants, dry lubricant (molybdenum disulfide) on space vehicles and resistant to high loads and [[temperature]s]. As a pure metal, molybdenum is used because of its high melting temperatures (4,730 degrees F.) as filament supports in light bulbs, metal-working dies and furnace parts. Molybdenum cathodes are used in special electrical applications. It can also be used as a catalyst in some chemical applications.

General uses for molybdenum are in machinery (35%), for electrical applications (15%), in transportation (15%), in chemicals (10%), in the oil and gas industry (10%), and assorted others (15%).

Substitutes and Alternative Sources

Possible substitutes for molybdenum as a strengthening alloy in steel include vanadium, chromium, columbium, and boron. However, such substitution is not presently practiced since molybdenum is plentiful, affordable, and effective.

Further Reading

- Common Minerals and Their Uses, Mineral Information Institute.

- More than 170 Mineral Photographs, Mineral Information Institute.

| Disclaimer: This article contains certain information that was originally published by the Mineral Information Institute. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the Mineral Information Institute should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |