Gulf of California harbor porpoise

Vaquita photo taken under permit (Oficio No. DR/488/08) from the Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT), within a natural protected area subject to special management and decreed as such by the Mexican Government. Credit: Paula Olson (NOAA Contractor) (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/)

The Gulf of California harbor porpoise (scientific name: Phocoena sinus and commonly known as the vaquita) is one of six species of marine mammal in the family Phocoenidae. The other five are the Finless porpoise, the Spectacled porpoise, the Harbour porpoise, Burmeister's porpoise, and Dall's porpoise. This cetacean is found only in the Gulf of California.

Since the Baiji (Lipotes vexillifer) was believed to have become extinct in 2006, the Vaquita has taken on the unfortunate title as the most endangered cetacean in the world. It also has the distinction of being the smallest porpoise species, a group of marine mammals that differ from dolphins in their stockier, robust body, lack of an elongated beak, and their distinctively shaped teeth. The Vaquita has a dark grey back and pale grey sides, blending into white on the underside, and there are highly conspicuous large black rings around its eyes and mouth. The fin on the back of its body, the dorsal fin, is proportionally taller than that of other porpoises and is roughly triangular, but curves slightly backwards.

Vaquita in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Source: Thomas Jefferson Vaquita in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Source: Thomas Jefferson

|

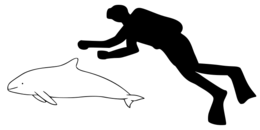

Size comparison of an average human against the Gulf of California harbor porpoise. Source: Chris Huh Size comparison of an average human against the Gulf of California harbor porpoise. Source: Chris Huh

|

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

The Vaquita is an elusive marine mammal, which surfaces slowly, barely disturbing the water's surface when it breathes and then quickly disappearing for long periods. It cryptic behaviour and rarity may be the reasons why little is known about the biology of the vaquita, except that most species births occur around March, gestation is believed to last around 10 to 11 months and one individual was estimated to have lived for 21 years.

Little is also known about the social organisation of this enigmatic species. While the Vaquita is most often seen in schools of one to three individuals, groups as large as eight or ten have been seen, and these small schools may form large, loose aggregations for short periods.

The Vaquita has a varied diet, comprising fish that live on or near the ocean bottom, squid and crustaceans. Like other cetaceans, the Vaquita produces high-frequency clicks which are used in echolocation. This may be used to locate their prey, but several of the fish species it feeds on are known to produce sound and so it is possible that the Vaquita locates them by following their sound, rather than by echolocating. In the murky waters of its habitat, echolocation may also be used to communicate with other vaquitas.

Contents

Physical Description

Adult Vaquitas are typically 1.2 to 1.5 meters in length with females being slightly larger than males. At birth their average length is 0.6 to 0.7m. Juveniles also have white spots on their dorsal fins. Phocoena sinus has between 34 to 40 teeth which are unicuspid, or "acorn like" (Silber, 1990) and a blunted rostral profile.

Phocoena sinus are physically similar to the Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) in many ways with an exception being that the vaquita is more slender. This has been explained in terms of their warmer habitat--the slender body increases surface area/volume ratio thus increasing heat dissipation in a warm environment. This explanation has also been used to argue the occurrence of larger appendages within this species (Hohn et al., 1996).

Other Physical Features: Endothermic; Homoiothermic; Bilateral symmetry

Behavior

Key species behaviors are: natatorial; motile; and solitary. Vaquitas have been observed singly or in small groups, indicating that they are primarily solitary individuals. Like many other phocoenids, Phocoena sinus uses sonar as a means of communicating and navigating through its habitat.

Reproduction

Key Reproductive Features: Polygynous mating system; Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual; Viviparous. Vaquitas are usually solitary. This would indicate a social system in which sperm competition is extremely important (Hohn et al., 1996). Within such systems, males attempt to maximize their fitness not by monopolizing access to females, but rather by mating with as many females as possible. As would be expected in multi-male breeding systems, male vaquitas have relatively large testes size in comparison to their body size.

Sexual maturity is believed to be reached between the ages of three and six years. Body mass may help to distinguish mature from immature specimens for both males and females (Hohn et al., 1996).

Vaquitas have highly seasonal reproduction. During the spring there is a complete lack of larger calves. The mating period is from mid-April to May, with a gestation period of roughly 10.6 months. Births occur at the beginning of the following March. Phocoena sinus have non-annual ovulation, thus they do not produce calves each year (Hohn et al., 1996). Females have one calf per pregnancy and lactate for less than one year.

Distribution and Movements

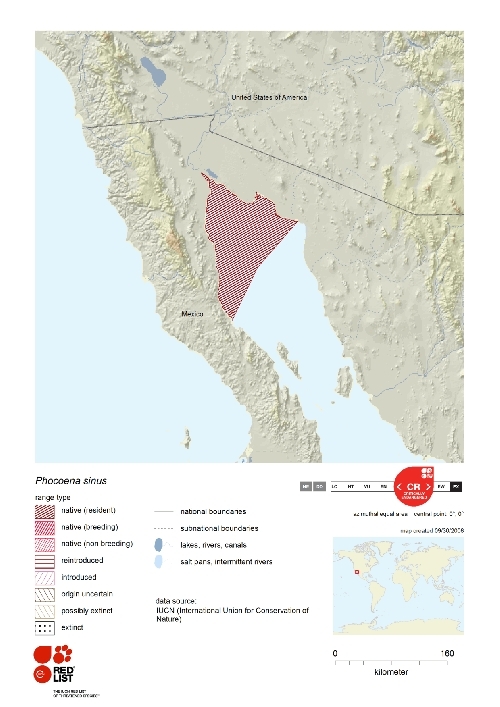

The range of Phocoena sinus is extremely restricted. This species of porpoise is found only in the northern end of the Gulf of California. Vaquita are found only in shallow water, close to shore.

The IUCN Red List notes that the "so-called 'core area' consists of about 2500 km² centred at Rocas Consag, some 40 km northeast of the town of San Felipe, Baja California. This core area straddles the southern boundary of the Upper Gulf of California and California River Delta Biosphere Reserve. There is no evidence to indicate that the vaquita's overall range has changed in historic times."

Habitat

This porpoise is found only in the coastal waters in the northern end of the Gulf of California. The Vaquita is that it is the only species of porpoise that is found in waters as warm as the Gulf of California. Most phocoenids are restricted to water cooler than 20 degrees Celsius, Vaquitas are unique in their ability to tolerate large annual fluctuations in temperature (Hohn, et al, 1996). The Gulf of California may experience temperature ranges from 14 degrees C in January to 36 degrees C in August. This may have an effect on the reproductive seasonality of this species.

The Vaquita is most often sighted in water 11 to 50 metrers deep, 11 to 25 kilometers from the coast, over silt and clay bottoms. Its habitat is characterised by turbid water with a high nutrient content.

Feeding Habits

Vaquitas feed on teleost fishes, mollusks and squid, which are found near the surface of the water. In several individuals the remains of Guld croakers were found.

Economic Importance for Humans

Phocoena sinus may interfere with human activity is in that it may inadvertantly become entangled in fishing nets set for shrimp, sharks, and totoabo causing a nuisance and possibly reducing catch during one net hauling.

This species is not used directly by humans. It is interesting in the sense that it is a unique phocoenid morphologically and behaviorally. The fact that it is limited in its range and is extremely endangered should encourage study of the vaquita.

Threats and Conservation Status

The IUCN Red List notes that "although imprecise because of variable sighting rates and other factors, the estimate of 567 (95% CI 177 to 1,073) was a great improvement on previous estimates and stands as the best currently available."

Further:

Mortality in gillnets of various mesh size has long been recognized as the most serious and immediate threat to the vaquita's survival (Vidal 1993, 1995; Reeves and Leatherwood 1994; IWC 1995:87, 167; Rojas-Bracho and Taylor 1999; Rojas-Bracho et al. 2006). The only available estimates of the vaquita bycatch rate are 39 (using one method) and 84 (using a different method) animals killed per year by boats from a single port (D'Agrosa et al. 2000). This alone would represent 7 or 15%, respectively, of the estimated total population size (Rojas-Bracho and Jaramillo-Legorreta 2002). Other potential threats that have been suggested but that appear not to be significant risk factors at present include inbreeding depression, pesticide exposure and ecological changes as a result of reduced flow from the Colorado River (Taylor and Rojas-Bracho 1999). The last of these may be important in the long term and deserves investigation.

The IUCN Red List adds:

Only approximately half of the "core area" of vaquita distribution falls within the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Delta Biosphere Reserve, which was created in 1993. Moreover, the nuclear zone of the Reserve, which is the only area where all fishing is prohibited, appears to be grossly mismatched with vaquita distribution as no sightings of vaquitas were made inside this zone during the two large-scale systematic surveys in the 1990s (Gerrodette et al. 1995, Jaramillo-Legorreta 1999).

An International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) was established in 1997 and has developed recommendations including: immediate prohibition of large-mesh gillnets throughout the species' known range, followed in sequence by bans on medium- and small-mesh gillnets; exclusion of gillnets and trawls within an enlarged biosphere reserve; and improved enforcement of fishing regulations in the northern Gulf generally. Considerable attention has also been given to development of less harmful fishing methods, alternative income-generating activities for fishing communities, and community-based education and awareness (Rojas-Bracho et al. 2006).

On 29 December 2005 the Mexican Ministry of Environment declared a Vaquita Refuge that contains within its borders approximately 80% of all verified vaquita sighting positions. In the same decree, the State Governments of Sonora and Baja California were offered $(US)1 million to compensate affected fishermen. The results of this action cannot yet be evaluated.

Time is quickly running out for the Vaquita, with a group of scientists in 2007 stating that they believed there were only two years remaining in which to find a solution to saving this species. Some measures have already been implemented; the Mexican government created the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Delta Biosphere Reserve in 1993 to protect the Vaquita and other endangered species. In 2005, the Government also created a Vaquita reserve, the area of which partially overlaps with the Biosphere Reserve. A ban on gill-net fishing is currently being enforced within the Vaquita reserve, but gill-netting and shrimp trawling continues in the Biosphere Reserve and elsewhere within the range of vaquita. Whilst these are incredibly important steps in the battle to save the Vaquita, if conservation efforts are not increased substantially the vaquita will become extinct. The Mexican government created the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA): a group of scientists from the UK, Canada, US and Mexico.

http://naturescrusaders.wordpress.com/ CIRVA recommends that the most critical measure for the conservation of the vaquita is to reduce bycatch to zero as soon as possible. This will need to be achieved by banning the use of all entangling fishing nets within the vaquitas range. Unfortunately, this is not an easy law to implement, as this will have a serious impact on the people whose livelihoods depend on fishing in the Gulf of California. Funds are urgently needed to buy out these net fisheries and to develop economic alternatives for those people affected. One can only hope that lessons are learnt from the tragic tale of the baiji and that necessary measures are implemented before the vaquita too is driven to extinction.

http://naturescrusaders.wordpress.com/ CIRVA recommends that the most critical measure for the conservation of the vaquita is to reduce bycatch to zero as soon as possible. This will need to be achieved by banning the use of all entangling fishing nets within the vaquitas range. Unfortunately, this is not an easy law to implement, as this will have a serious impact on the people whose livelihoods depend on fishing in the Gulf of California. Funds are urgently needed to buy out these net fisheries and to develop economic alternatives for those people affected. One can only hope that lessons are learnt from the tragic tale of the baiji and that necessary measures are implemented before the vaquita too is driven to extinction.

Vaquita are listed as critically endangered. They are perhaps the most endangered of the cetaceans with only a few hundred remaining. Phocoena sinus are often caught in fishing nets which are set to catch other marine animals, most often shrimp. This species becomes entangled either in the shrimp nets or within gillnet fisheries for sharks. It is estimated that 25-30 individuals drown each year as a result. To further complicate the situation, relatively few individuals reach maturity because of the high mortality of young individuals (they are highly susceptible to being netted), and the remaining older individuals are approaching the upper limit of their lifespan so as to be contributing little to future reproduction (Hohn et al, 1996).

IUCN Red List: Critically Endangered

US Federal List: Endangered

CITES: Appendix I

References

- Rojas-Bracho, L., Reeves, R.R., Jaramillo-Legorreta, A. & Taylor, B.L. 2008. Phocoena sinus. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. Downloaded on 28 April 2011.

- "Phocoena sinus Norris and McFarland, 1958". Encyclopedia of Life, available from "http://www.eol.org/pages/328537". Accessed 01 May 2011.

- Landes, D. 2000. Phocoena sinus (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 01, 2011

- Vaquita (Phocoena sinus) , Arkive.Downloaded on 28 April 2011.

- Barlow, J. (2008) Pers. Comm.

- Barlow, J., Gerrodette, T. and Silber, G. 1997. First estimates of Vaquita abundance.

- Brownell Jr., R.L., Findley, L.T., Vidal, O., Robles, A. and Manzanilla, S.N. (1987) External morphology and pigmentation of the vaquita Phocoena sinus (Cetacea: Mammalia). Marine Mammal Science, 3 : 22 - 30.

- Brownell, Robert L. Jr. 1983. Phocoena sinus. Mammalian Species, no. 198. 1-3

- Culik, B.M. (2004) Review of Small Cetaceans. Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats. UNEP / CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany.Hershkovitz, Philip. 1966. Catalog of Living Whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246. viii + 259

- D'Agrosa, C., Lennert-Cody, C. E. and Vidal, O. 2000. Vaquita bycatch in Mexico's artisanal gillnet fisheries: driving a small population to extinction. Conservation Biology 14: 1110?1119.

- D'Agrosa, C., Vidal, O. and Graham, W. C. 1995. Mortality of the Vaquita (Phocoena sinus) in gillnet fisheries during 1993-94. Report of the International Whaling Commission 16: 283?291.

- Groombridge, B. (ed.). 1994. 1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Hohn, A., A. Read, S. Fernandez, O. Vidal, L. Findley. 1996. Life History of the Vaquita, Phocoena sinus. Journal of Zoology, 239: 235-251.

- IUCN. 1990. 1990 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- IUCN. 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (Accessed: 5 October 2008).

- IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre. 1986. 1986 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre. 1988. 1988 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Jaramillo-Legorreta, A. M., Rojas-Bracho, L. and Gerrodette, T. 1999. A new abundance estimate for Vaquitas: first step for recovery. Marine Mammal Science 15: 957-973.

- Jaramillo-Legorreta, A., Rojas-Bracho, L., Brownell Jr, R.L., Read, A.J., Reeves, R.R., Ralls, K. and Taylor, B.L. (2007) Saving the vaquita: immediate action, not more data. Conservation Biology, 21 : 1653 - 1655.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Perrin, W. (2010). Phocoena sinus Norris & McFarland, 1958. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database, Downloaded on 28 April 2011.

- Read, A.J. (2002) Porpoises, Overview. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Reeves, R.R., Smith, B.D., Crespo, E.A. and Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. (2003) Dolphins, Whales and Porpoises: 2002–2010 Conservation Action Plan for the World's Cetaceans. IUCN/SSC Cetacean Specialist Group, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Rojas-Bracho, L. and Taylor, B.L. (1999) Risk factors affecting the vaquita. Marine Mammal Science, 15 : 974 - 989.

- Rojas-Bracho, L., Reeves, R.R. and Jaramillo-Legorreta, A. (2006) Conservation of the vaquita Phocoena sinus. Mammal Review, 36 : 179 - 216.

- Rojas-Bracho, L. and Jaramillo-Legorreta, A. (2002) Vaquita. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Silber, G. 1990. Occurrence and Distribution of the Vaquita Phocoena sinus in the Northern Gulf of California. Fishery Bulletin, 88, no #2: 339-346.

- Turvey, S.T., Pitman, R.L., Taylor, B.L., Barlow, J., Akamatsu, T., Barrett, L.A., Zhao, X., Reeves, R.R., Stewart, B.S., Wang, K., Wei, Z., Zhang, X., Pusser, L.T., Richlen, M., Brandon, J.R. and Wang, D. (2007) First human-caused extinction of a cetacean species?. Biology Letters, 3: 537 - 540.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Vidal, O. 1995. Population biology and incidental mortality of the Vaquita, Phocoena sinus. Report of the International Whaling Commission 16: 247?272.

- Vidal, O., Brownell Jr., R. L. and Findley, L. T. 1999. Vaquita Phocoena sinus Norris and McFarland, 1958. In: S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds), Handbook of Marine Mammals. Volume 6: The Second Book of Dolphins and the Porpoises, pp. 357?378. Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA.

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv