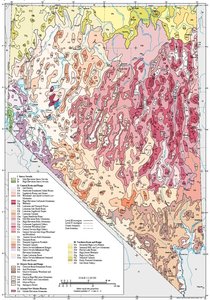

Ecoregions of Nevada

Ecoregions of Nevada. (Source: USEPA)

Ecoregions of Nevada. (Source: USEPA) The Ecoregions of Nevada consist of a large number of disparate ecosystem types. Despite the general aridity, there are a number of locations that feature prominent forests and even wetlands. There are also extremely diverse characteristics of climate, topography and soils among the ecoregions of Nevada.

Contents

Taxonomy of the Ecoregions

Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment) of ecosystems and ecosystem components. By recognizing the spatial differences in the capacities and potentials of ecosystems, ecoregions stratify the environment by its probable response to disturbance.[1] Ecoregions are general purpose regions that are critical for structuring and implementing ecosystem management strategies across federal agencies, state agencies, and nongovernmental organizations that are responsible for different types of resources in the same geographical areas.[2]

The approach used to compile this map is based on the premise that ecological regions can be identified through the analysis of the spatial patterns and the composition of biotic and abiotic phenomena that affect or reflect differences in ecosystem quality and integrity.[3,4,5] These phenomena include geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, and hydrology. The relative importance of each phenomenon varies from one ecological region to another regardless of ecoregion hierarchical level. A Roman numeral hierarchical scheme has been adopted for different levels of ecological regions. Level I (Ecoregions of Nevada) is the coarsest level, dividing North America into 15 ecological regions. Level II (Ecoregions of Nevada) divides the continent into 52 regions. [6]At Level III (Ecoregions of Nevada), the continental United States contains 104 ecoregions and the conterminous United States has 84 ecoregions.[7] Level IV (Ecoregions of Nevada) is a further subdivision of level III ecoregions. Explanations of the methods used to define the USEPA’s ecoregions are given in Omernik (1995), Omernik and others (2000), Griffith and others (1994), and Gallant and others (1989).

Nevada’s physiography is composed of a repeating pattern of fault block mountains and intervening valleys. Valleys are shrub-covered or shrub- and grass-covered. Mountains may be brush-, woodland-, or forest-covered. Land use is primarily rangeland but many mines and large military reservations occur. Some valleys are irrigated and farmed, and rapid urban and suburban growth is occurring in the Las Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. There are 5 level III ecoregions and 43 level IV ecoregions in Nevada and many continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states.[8,9]

The level III and IV ecoregion map on this poster was compiled at a scale of 1:250,000 and depicts revisions and subdivisions of earlier level III ecoregions that were originally compiled at a smaller scale.[7,4] This poster is part of a collaborative project primarily between USEPA Region 9, USEPA National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (Corvallis, Oregon), Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources–Division of Environmental Protection, Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources–Nevada Natural Heritage Program, United States Department of Agriculture–Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), United States Department of the Interior–Bureau of Land Management (BLM), United States Department of the Interior–Fish and Wildlife Service, and United States Department of the Interior–Geological Survey (USGS)–Earth Resources Observation Systems (EROS) Data Center.

The Nevada ecoregion project is associated with an interagency effort to develop a common framework of ecological regions. Reaching that objective requires recognition of the differences in the conceptual approaches and mapping methodologies applied to develop the most common ecoregion-type frameworks, including those developed by the USFS,[10] the USEPA, [4,5] and the NRCS.[11] As each of these frameworks is further refined, their differences are becoming less discernible. Regional collaborative projects, such as this one in Nevada, where agreement has been reached among multiple resource management agencies, are a step toward attaining consensus and consistency in ecoregion frameworks for the entire nation.

Abstracts of the EPA Ecoregions of Nevada

The following summaries set forth the entirety of Nevada's ecoregions as delineated by the U.S. EPA after consultation with other relevant federal and state of Nevada agencies:

|

5. Sierra Nevada | |

|

5a. Within Nevada, the Mid-Elevation Sierra Nevada ecoregion begins abruptly in the foothills of the Carson Range at the western edge of the state. Physiographically, the Carson Range is a Great Basin fault block mountain range, but its geology and forest type are more typical of the Sierra Nevada. The mid-elevation dry forest of Ecoregion 5a contains a diverse mix of conifers, including Jeffrey pine, sugar pine, incense cedar, and California white fir. The understory includes sagebrush, antelope bitterbrush, and a fire-maintained chaparral component of snowbrush and manzanita. The amount of pinyon–juniper woodland in Ecoregion 5a is insignificant in contrast to other Nevada ecoregions in this elevation range. |

|

|

13. Central Basin and Range | |

|

13a. The Salt Deserts ecoregion is composed of nearly level playas, salt flats, mud flats, and saline lakes. These features are characteristic of those in the Bonneville Basin; they have a higher salt content than the Lahontan and Tonopah Playas (13h). Water levels and salinity fluctuate from year to year; during dry periods salt encrustation and wind erosion occur. Vegetation (Land-cover) is mostly absent although scattered salt-tolerant plants, such as pickleweed, iodinebush, black greasewood, and inland saltgrass, occur. Soils are not arable, and there is very limited grazing potential. The salt deserts provide wildlife habitat, and serve some recreational, military, and industrial uses. |

Wild horses are protected in Nevada and their populations are monitored and managed. Though wild horses compete with livestock and wildlife for limited forage, their presence is tolerated because many consider them part of our national heritage. (Photo: State of Nevada, Commission for the Preservation of Wild Horses) Wild horses are protected in Nevada and their populations are monitored and managed. Though wild horses compete with livestock and wildlife for limited forage, their presence is tolerated because many consider them part of our national heritage. (Photo: State of Nevada, Commission for the Preservation of Wild Horses)  Mountain ranges above 8,000 feet have varying degrees of forest cover depending upon precipitation, substrate, soil type, aspect, and slope. The High Elevation Carbonate Mountains (13e) are pictured here. Ecoregion 13e receives some summer precipitation, and is characteristically underlain by limestone and dolomite. Mountain ranges above 8,000 feet have varying degrees of forest cover depending upon precipitation, substrate, soil type, aspect, and slope. The High Elevation Carbonate Mountains (13e) are pictured here. Ecoregion 13e receives some summer precipitation, and is characteristically underlain by limestone and dolomite.  Bristlecone pines are endemic to the Great Basin and northern Mojave Desert. They occur in scattered groves near timberline, where individuals have been found to exceed 4,000 years of age. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Bristlecone pines are endemic to the Great Basin and northern Mojave Desert. They occur in scattered groves near timberline, where individuals have been found to exceed 4,000 years of age. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  Subsurface water that percolated through the porous limestone and dolomite of the RubyMountains (in Ecoregions 13n and 13o) resurfaces to the east as seeps and springs. The Ruby Marshes in Ecoregion 13g provide crucial nesting and feeding grounds for wildlife. (Photo: State of Nevada, Division of Environmental Protection) Subsurface water that percolated through the porous limestone and dolomite of the RubyMountains (in Ecoregions 13n and 13o) resurfaces to the east as seeps and springs. The Ruby Marshes in Ecoregion 13g provide crucial nesting and feeding grounds for wildlife. (Photo: State of Nevada, Division of Environmental Protection)  The scarcity of water in the Central Basin and Range (13) creates conflicts among competing users. Lake Winnemucca (in Ecoregions 13h and 13j) disappeared during the last century when it no longer received water from Pyramid Lake due to increased withdrawals for irrigation and urbanization. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) The scarcity of water in the Central Basin and Range (13) creates conflicts among competing users. Lake Winnemucca (in Ecoregions 13h and 13j) disappeared during the last century when it no longer received water from Pyramid Lake due to increased withdrawals for irrigation and urbanization. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  The Lahontan cutthroat trout occurs in the Truckee River-Pyramid Lake system of Ecoregion 13j and in perennial streams draining the Sierra Nevada in Ecoregions 13x and 13aa. Their numbers are declining due to loss of habitat, diversion of perennial streams, and competition with introduced game fish. (Photo: Gary Vinyard, University of Nevada-Reno, Biological Resources Research Center) The Lahontan cutthroat trout occurs in the Truckee River-Pyramid Lake system of Ecoregion 13j and in perennial streams draining the Sierra Nevada in Ecoregions 13x and 13aa. Their numbers are declining due to loss of habitat, diversion of perennial streams, and competition with introduced game fish. (Photo: Gary Vinyard, University of Nevada-Reno, Biological Resources Research Center)  Lack of precipitation and shallow, gravelly soil complicates grazing management in the CentralBasin and Range (13). The sparse vegetative cover is easily over-grazed as shown here in the Carbonate Sagebrush Valleys (13p). (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Lack of precipitation and shallow, gravelly soil complicates grazing management in the CentralBasin and Range (13). The sparse vegetative cover is easily over-grazed as shown here in the Carbonate Sagebrush Valleys (13p). (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  The alpine zone of the Central Nevada Bald Mountains (13t) is characterized by a bare, windblown, gravelly substrate and scattered alpine forbs. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) The alpine zone of the Central Nevada Bald Mountains (13t) is characterized by a bare, windblown, gravelly substrate and scattered alpine forbs. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  The White Mountains, and other parts of the Sierra Nevada-Influenced Ranges (13x), receive enough rainfall to support various Sierra Nevada plant and animal species. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) The White Mountains, and other parts of the Sierra Nevada-Influenced Ranges (13x), receive enough rainfall to support various Sierra Nevada plant and animal species. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  Desert peach has somewhat higher moisture requirements than other plants in the semiarid shrub community. It grows in western Nevada in the Sierra Nevada- Influenced Semiarid Hills and Basins (13aa) (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Desert peach has somewhat higher moisture requirements than other plants in the semiarid shrub community. It grows in western Nevada in the Sierra Nevada- Influenced Semiarid Hills and Basins (13aa) (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) |

|

14. Mojave Basin and Range | |

|

14a. The Creosote Bush-Dominated Basins ecoregion includes the valleys lying between the scattered [[mountain] ranges] of the Mojave Desert at elevations ranging from 1,800 to 4,500 feet. Elevations are lower, soils are warmer, and evapotranspiration is higher than in the Central Basin and Range (13) to the north. Limestone- and gypsum-influenced soils occur, but overall, precipitation amount has a greater ecological significance than geology. Toward the south and east, as summer rainfall increases, the Sonoran influence grows, and woody leguminous species, such as mesquite and acacia, become more common. Creosote bush, white bursage, and galleta grass characterize the plant community of Ecoregion 14a. Pocket mice, kangaroo rats, and desert tortoise are faunal indicators of the desert environment. Desert willow, coyote willow, and mesquite grow in riparian areas, although the alien invasive tamarisk is rapidly replacing native desert riparian vegetation. |

The numbers of desert bighorn sheep have declined due to loss of habitat, past overhunting, and disease carried by domestic livestock. There has been some success in maintaining their numbers in protected wilderness areas through reintroductions and the exclusion of livestock. (Photo: Glenn Vargas, California Academy of Sciences) The numbers of desert bighorn sheep have declined due to loss of habitat, past overhunting, and disease carried by domestic livestock. There has been some success in maintaining their numbers in protected wilderness areas through reintroductions and the exclusion of livestock. (Photo: Glenn Vargas, California Academy of Sciences)  Desert tortoise numbers have declined precipitously in the last 20 years. The desert tortoise is easy prey to hunters, off-road vehicles, and urban development. (Photo: Glenn Clemmer, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Desert tortoise numbers have declined precipitously in the last 20 years. The desert tortoise is easy prey to hunters, off-road vehicles, and urban development. (Photo: Glenn Clemmer, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  Ash Meadows is a system of springs, seeps, and ponds in the Amargosa Desert (14g). (Photo: State of Nevada, Division of Environmental Protection) Ash Meadows is a system of springs, seeps, and ponds in the Amargosa Desert (14g). (Photo: State of Nevada, Division of Environmental Protection) |

|

22. Arizona/New Mexico Plateau | |

|

22d. The Middle Elevation Mountains ecoregion, represented in southeastern Nevada by the Virgin Mountains, is a small portion of the Arizona/New Mexico Plateau (22). Its woodland zone differs from the woodlands of other mountainous areas in the Great Basin in the prevalence of interior chaparral species, such as Gambel oak, desert scrub oak, and canyon maple, interspersed with the pinyon and juniper. On the lower slopes, juniper mixes with Joshua tree and Mojave yucca; here, woodland starts at a lower elevation (about 4,000 feet) than in the Mojave Desert or Great Basin. Broad areas of mountain brush grow on upland slopes above the woodland. Isolated pockets of Rocky Mountain white fir and Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir also occur. They are outliers of a higher montane zone that is not extensive enough to map in Nevada. |

The mountains, buttes, and canyons of the Arizona/New Mexico Plateau (22). (Photo: NRCS) The mountains, buttes, and canyons of the Arizona/New Mexico Plateau (22). (Photo: NRCS) |

|

80. Northern Basin and Range | |

|

80a. The Dissected High Lava Plateau ecoregion is a broad to gently rolling basalt plateau cut by deep, sheer-walled canyons and covered with vast expanses of sagebrush. Ecoregion 80a differs from other sagebrush-dominated ecoregions in Nevada, such as Ecoregions 13c, 13p, 13k, and 13v, in having higher precipitation and colder winters. Cool season grasses, such as bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue, are associated with the sagebrush. Understory species are denser and biological soil crusts tend to be more extensive and in better condition than in other ecoregions at similar elevations farther south in Nevada. Ecoregion 80a drains externally to the Snake River, unlike the similar High Lava Plains (80g) that are internally drained. |

Fewer mountain ranges occur in the Northern Basin and Range (80) than in the Central Basin and Range (13). Broad plains covered in sagebrush steppe, rimrock, and rocky uplands are typical of Ecoregion 80. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Fewer mountain ranges occur in the Northern Basin and Range (80) than in the Central Basin and Range (13). Broad plains covered in sagebrush steppe, rimrock, and rocky uplands are typical of Ecoregion 80. (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  Biological soil crusts are composed of cyanobacteria, mosses, and lichens. They cover the dry desert floor and protect it from erosion. (Photo: Eric Peterson, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Biological soil crusts are composed of cyanobacteria, mosses, and lichens. They cover the dry desert floor and protect it from erosion. (Photo: Eric Peterson, Nevada Natural Heritage Program)  Open pit gold mines are common in the Independence Range (80j). (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) Open pit gold mines are common in the Independence Range (80j). (Photo: Jim Morefield, Nevada Natural Heritage Program) |

Bibliography

- The full version of this entry is located at: http://www.epa.gov/wed/pages/ecoregions/nv_eco.htm. That description contains additional maps, as well as information on the physiography, geology, soil, potential natural vegetation, and the land use and land cover of the ecoregion.

- PRINCIPAL AUTHORS: Sandra A. Bryce (Dynamac Corporation), Alan J. Woods (Dynamac Corporation), James D. More&Mac222;eld (Nevada Natural Heritage Program), James M. Omernik (USEPA), Thomas R. McKay (NRCS), Gary K. Brackley (NRCS), Robert K. Hall (USEPA), Damian K. Higgins (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), David C. McMorran (USFS), Karen E. Vargas (Nevada Division of Environmental Protection), Eric B. Petersen (Nevada Natural Heritage Program), Desiderio C. Zamudio (USFS), and Jeffrey A. Comstock (Indus Corporation).

- COLLABORATORS AND CONTRIBUTORS: Bill Brooks (BLM), Robin Tausch (USFS–Rocky Mountain Research Station), and Bill W. Daily (NRCS).

- REVIEWERS: Edgar F. Kleiner (Emeritus Professor, University of Nevada-Reno), Frederick F. Peterson (Emeritus Professor, University of Nevada-Reno), Harold Klieforth (Emeritus, Associate Research Meteorologist, Desert Research Institute), David Charlet (Professor, Community College of Southern Nevada), David A. Mouat (Associate Research Professor, Earth and Ecosystems Sciences, Desert Research Institute), Glenn Gentry (Supervisor, Water Quality Monitoring, Nevada Division of Environmental Protection), and Mark Warren (Staff Biologist, Nevada Division of Wildlife).

- CITING THIS POSTER: Bryce, S.A., Woods, A.J., Morefield, J.D., Omernik, J.M., McKay, T.R., Brackley, G.K., Hall, R.K., Higgins, D.K., McMorran, D.C., Vargas, K.E., Petersen, E.B., Zamudio, D.C., and Comstock, J.A., 2003, Ecoregions of Nevada (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,350,000).

- This project was partially supported by funds from the USEPA– Office of Research and Development’s Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program through contract 68-C6-005 to Dynamac Corporation.

Works cited

- Bryce, S.A., Omernik, J.M., and Larsen, D.P., 1999, Ecoregions—a geographic framework to guide risk characterization and ecosystem management: Environmental Practice, v. 1, no. 3, p. 141-155.

- Omernik, J.M., Chapman, S.S., Lillie, R.A., and Dumke, R.T., 2000, Ecoregions of Wisconsin: Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, v. 88, p. 77-103.

- Wiken, E., 1986, Terrestrial ecozones of Canada: Ottawa, Environment Canada, Ecological Land Classification Series no. 19, 26 p. ISBN: 0662147618.

- Omernik, J.M., 1987, Ecoregions of the conterminous United States (map supplement): Annals of the Association of American Geographers, v. 77, p. 118-125, scale 1:7,500,000.

- Omernik, J.M., 1995, Ecoregions—a framework for environmental management in Davis, W.S. and Simon, T.P., editors, Biological assessment and criteria-tools for water resource planning and decision making: Boca Raton, Florida, Lewis Publishers, p. 49-62. ISBN: 0873718941.

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America—toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2002, Level III ecoregions of the continental United States (revision of Omernik, 1987): Corvallis, Oregon, USEPA–National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Map M-1, various scales.

- (McGrath and others, 2002; no reference for this one?

- Woods, A.J., Lammers, D.A., Bryce, S.A., Omernik, J.M., Denton, R.L., Domeier, M., and Comstock, J.A., 2001, Ecoregions of Utah: Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,175,000).

- Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture–Soil Conservation Service, 1981, Land resource regions and major land resource areas of the United States: Agriculture Handbook 296, 156 p.

Further Reading

- Gallant, A.L., Whittier, T.R., Larsen, D.P., Omernik, J.M., and Hughes, R.M., 1989, Regionalization as a tool for managing environmental resources: Corvallis, Oregon, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA/600/3-89/060, 152 p.

- Griffith, G.E., Omernik, J.M., Wilton, T.F., and Pierson, S.M., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of Iowa – a framework for water quality assessment and management: Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science, v. 101, no. 1, p. 5-13.

- J.A., Shelden, J., Crawford, R.C., Comstock, J.A., and Plocher, M.D., 2002, Ecoregions of Idaho: Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,350,000).

- McMahon, G., Gregonis, S.M., Waltman, S.W., Omernik, J.M., Thorson, T.D., Freeouf, J.A., Rorick, A.H., and Keys, J.E., 2001, Developing a spatial framework of common ecological regions for the conterminous United States: Environmental Management, v. 28, no. 3, p. 293-316.

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the Environmental Protection Agency. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the Environmental Protection Agency) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |