Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study

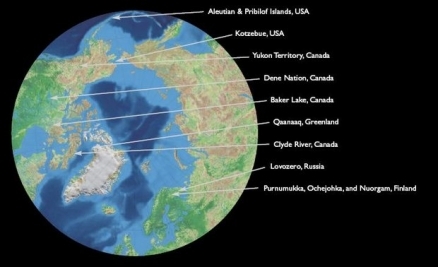

This is Section 3.4.4 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; one of nine Arctic climate change case studies using indigenous knowledge.

Case Study Authors: Denendeh: Chris Paci, Shirley Tsetta, Chief Sam Gargan, Chief Roy Fabian, Chief Jerry Paulette,Vice-Chief Michael Cazon, Sub-Chief Diane Giroux, Pete King, Maurice Boucher, Louie Able, Jean Norin, Agatha Laboucan, Philip Cheezie, Joseph Poitras, Flora Abraham, Bella T'selie, Jim Pierrot, Paul Cotchilly, George Lafferty, James Rabesca, Eddie Camille, John Edwards, John Carmichael,Woody Elias, Alison de Palham, Laura Pitkanen, Leo Norwegian

This case study is the first official publication of Dene observations and knowledge on climate change. There have been documents by newcomers, missionaries, fur traders, and others, in which it was observed and noted that the Dene knew much about their relationship with the land. There have been articles and books written on the problems of relying on these observations[1]. The Dene are continuing to write their histories and curriculum for their schools, teaching us about their world, but these are beyond this discussion[2].

Raven is known as a trickster. He said let’s see who can kill a moose. So everyone ran into the bush. The Raven said he killed a moose. The people asked what are we going to do with the intestines? They said to string it along the creek. They were melting the grease into the intestine. (This was the first pipeline). They were wondering why this grease was never filling up. So a couple of kids followed him. They found the Raven at the end drinking the grease. So they threw a bone in the grease. The Raven swallowed the bone. That’s why the Raven today says, KAA! —Bella T’selie, Liidlii Kue, Denendeh, March 12, 2003

My mother used to get the best water and spruce bough for the floor. It was natural. Even if we spilt something it would seep through the spruce bough. So when we lived in a house we didn’t know how to make the transition. People got sick. There’s not many people who can live in both worlds. We have sacred lands that we don’t go into. We knew of this one area to be a bad place (Deline). After development, we found out how bad it really was. Scientists like to talk about things apart. We think in holistic terms and cannot think about things separately. Dene spirituality is in traditional knowledge. Dene ways are very formal. We cannot separate spirituality in Dene, but scientists think this is ridiculous. —Bella T’selie, Liidlii Kue, Denendeh, March 12, 2003

We survive by caribou. When you hunt caribou it can take up to three weeks for the trip. That’s why we need to protect our caribou. That’s why I brought some caribou for you to taste. —Eddie Camille, Liidlii Kue, Denendeh, March 11, 2003

Like all environmental issues, climate change is understood and talked about by the Dene (Chief Roy Fabian in Dene Nation, 2002, Chief Sam Gargan in Dene Nation, 2003) as it relates to the people and the land[3]. Denendeh will face significant change based on current climate change scenarios and models. The issues of changing climate are different for Dene than they are for other indigenous peoples and each has much to contribute to this discussion. Dene knowledge speaks to the past, and explains the now, as well as what may occur in the future. This knowledge is different from what scientists know about climate change (see for example the discussion on climate and the high Arctic[4]). Each form of knowledge can be gathered together, not necessarily to create a single synthesis, but to allow each to appreciate and increase what is known about climate change from both perspectives. The Denendeh Environmental Working Group workshops are a first step in a larger effort to bring Dene views and voices into climate change discussions in the north, in Canada, and into international discussions such as the SnowChange Conference (see Section 3.4.7 (Denendeh: the Dene Nations Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study)) and this assessment.

Contents

Dene Nation (3.4.4.1)

Dene Nation is a non-profit Aboriginal governmental organization mandated to retain sovereignty by strengthening Dene spiritual beliefs and cultural values in Denendeh, which encompasses five culturally and geographically distinct areas, six language groups, and is home to over 25,000 Dene in twenty-nine communities. The settlement of communities has varied as has the population and composition of each community. As indigenous peoples their cultures, languages, and title come from time immemorial. In the international arena the Dene use the Arctic Athabaskan Council, a Permanent Participant to the Arctic Council, and the Assembly of First Nations. These links enable the Dene to tackle difficult science and policy issues of climate change by maintaining activities at the local to international level.

Climate change policies and programs in Denendeh (3.4.4.2)

The Dene have always observed the climate and have stories that speak about the way things were before time and as they are meant to be in the future. Climate change, as discussed here, is concerned with the phenomenon that has been speeding up following industrialization. Since the 1970s, a great deal of what has entered into Dene thinking has come from international discussions of greenhouse gas emissions and global warming[5]. Changing climate is indeed being experienced as local changes on the land; however, policies and programs dealing with these changes often have little to do with the needs of the people on the land.

In order to discuss Dene knowledge, impacts, and adaptations of changes in climate, it is first important to place into context the reason why Dene observations and knowledge are being documented. The development of national government policy and programs has had a significant influence on Dene understanding of climate change and a brief summary of government policy and programs provides the context from which to understand the development of the Denendeh Environmental Working Group.

The Canadian government’s initiatives fund a variety of activities. The general direction for the bulk of these programs, toward national objectives, means that there is a limited engagement for Dene in these activities. Work at the local level must serve some national priority or it is not funded. For example, taken to its full extent the development of the Hub Pilot Advisory Team and the Public Education Outreach gives the appearance of democratic and public institutions responding to national information needs surrounding climate change. Likewise, the Canadian Climate Impacts and Adaptation Research Network facilitates a transparent network of researchers and government scientists working collectively on climate change. These and other activities appear to be developing a critical mass of information, but are not focused on the specific or local realities of climate change in any single location; how it is being experienced. The Joint Ministers of Energy and Environment are not concerned specifically with the fact that indigenous peoples across the north are experiencing climate change differently. In order to counter the homogenizing influence of federal programs, limited attempts, in particular the Northern Ecosystem Initiative under Environment Canada, have evolved, responding to particular realities of northern Canada and the indigenous peoples living there.

Northern indigenous peoples’ organizations in Canada have approached climate change independently and the result has been a piece-meal approach to bringing forward indigenous views and knowledge. Hearing from the people themselves is important[6]. Equally important is finding ways to interpret what is being said by these people to those who lack the historical and anthropological knowledge necessary to understand fully what is being said[7]. This is particularly pronounced in climate change research because of its heavy reliance on physical scientists who may wrongly conclude that indigenous knowledge is anecdotal and therefore without scientific value[8]. Dene Nation decided that the most efficient way of contributing to discussions on climate change was by sharing some of what was gathered during workshops where Dene knowledge could be shared and documented.

Denendeh Environmental Working Group (3.4.4.3)

The Denendeh Environmental Working Group (DEWG) developed out of two complementary forces. First, a number of climate change issues were of interest to the Dene and had broad policy/program implications for Denendeh. Second, the Environment and Lands division of Dene Nation had previous experience with a Denendeh environment committee. Dene Nation’s objective in forming the DEWG was to work on specific areas of collective interest, to educate about the issues and best apply the policies and programs that exist, and to lobby in all arenas regarding Dene sovereignty, spiritual beliefs, and cultural values.

The DEWG is a non-political forum where Dene and invited guests from government, academia, and non-governmental organizations can gather to share climate change knowledge and observations. The first workshop on climate change was held in Thebachaghe (Fort Smith) in 2002. The second, held in Liidlii Kue (Fort Simpson) in 2003, examined climate change and forests. Themes of future workshops include water and fish.

The DEWG membership changes with each meeting, but includes one technical staff member working on environment and lands issues from each region and a regional elder. There are a number of concerns about changes in climate that are specific and unique, as well as others that are common to each Dene community and region. These differences and commonalities are recognized and the issues and knowledge brought forward during each meeting are documented. The mixture of tradition and modernity find common hearing and attempts are made to improve what is known from both traditional knowledge and practices and science and government policy and programs. In the future, transcripts and tapes could serve a number of educational and other research purposes. The work of documenting Dene concerns and responses to climate change is still in its infancy. Conclusions should not be drawn on impacts and adaptations until a critical mass of information is gathered, the definition of which was an important consideration during the DEWG meetings during 2003 and 2004.

The DEWG facilitates more than the documentation of Dene views and knowledge on climate change issues. A significant goal is to facilitate the sharing among regions of climate change knowledge in a systematic way. The workshops are proving to be an opportunity for people from each region to hear from one another about changes they have observed.

The broad nature of climate change research and programs is being complemented and improved by focusing at the regional and local levels. The DEWG is important for education and outreach. In particular, each meeting challenges the participants to find ways to communicate the sometimes-complex science of climate change in a way that is accessible and free from technical jargon. It challenges elders and technical staff to speak with scientists and build, when necessary, research alliances and networks of researchers.

The DEWG has been shaped by four basic discussion questions:

- Is there a difference today in Denendeh and is climate change having a role in these changes, what else may be causing it?

- What climate change programs are there and how can our communities be more involved in research and communication about these changes?

- If it is important to document Dene climate change views/knowledge, how should we communicate this knowledge with each other and to policymakers, governments, and others outside the north?

- Is the DEWG a good mechanism to discuss climate change, what should we be talking about, and what else do we need to do?

Answers to these questions continue to evolve. Elders, in particular, find that there is a difference in how the climate is changing in Denendeh, and that many changes on the land are attributed to climate change, or that climate change is at least having a role in the land and animals being different. The behavior of Dene themselves, including increased use of transportation like vehicles and skidoos, is blamed in part for increased changes in the climate and overall health of Denendeh.

Change is manifest in how animals behave, such as wolves acting unpredictably. Invasive species, such as moose moving further north and buffalo (Bison bison) moving into Monfwi region, are being observed. Birds never before seen and increasing variations in insects are also being noted. A problem identified for trees was increased pine and spruce parasites and diseases.

The overall health of trees and their ability to fight disease and withstand the increased frequency of insect infestations is of concern for forests in Denendeh. For the past five to six years, trees have been dying in greater numbers. Elders noted that trees were soggy and not frozen through so that in cases of emergency one could not easily save oneself by making a fire. This was serious as ice was unpredictable in places and there were increased instances of people falling through.

In the Mackenzie Delta, many channels had changed with some widening, making winter land travel impossible. Groundwater is down in some areas because of increased levels of vegetation, especially willows. Changes in vegetation were not the cause but rather the effect of climate change. Changes in water also lead to increased disease in wildlife. Elders are observing how many freshwater fish populations and runs are less healthy, there is increased occurrence of "unhealthy fish".

Interconnectedness among all parts of the environment is a feature repeated by elders during the workshops. The links between activities on the land, development impacts, lack of capacity to deal with change, and the overall adaptive ability of Dene cultures are important considerations. For the Dene, it is wrong to separate climate change from human and governance issues. Dene talk about climate change in part as "how things grow"[9].

Climate change is affecting how traditions are maintained. It is difficult to demonstrate to non-Dene the impacts of climate change on traditions and to identify those impacts that have other sources, for example television. The changes and associated impacts are known by elders and others who continue Dene traditions, and stem from the overall unpredictability of climate and increased warming which alters the availability of species and so on. An indication of the erosion of traditions is that, "in the old days, everything was dried; meat and fish". Less food is dried now. For example, the organizers of the DEWG workshops could not secure an adequate supply of dry fish and dry meat for participants, even though these foods were once abundant in Dene communities. There are very good lunches but typically few traditional foods are served. In the future the supply of food and food preparation methods will be questioned in more detail. In this point lies the strength of having a series of workshops by and for the Dene on climate change and associated issues; to continue to learn and to share/protect Dene observations and knowledge.

Traditional knowledge teaches Dene about relationships, to know how things are related to each other. So for example, when asking how trees are affected by changes in climate, it may be appropriate to consider what is happening with drinking water. The relationship may be that there are different trees now, the willows having replaced spruce and other trees dying off, while the water tastes bad because of warming. Seen in this way, the entire world relates to all other parts, including the Dene.

Dene explain both the causes of climate change and the future in terms of their daily lives and cultural understandings. The physical connections Dene have with the land have been much discussed; always with an underlying concern about more than just the physical and immediate concerns of everyday life. What a person does affects everyone else, whether it is throwing garbage into the river and affecting those downstream, or the way that cities create huge ecological footprints from car exhaust, factories, and industries. Also, what was done in the past affects now and into the future.

The integrity of culture and land is essential to Dene. They have made many observations and see climate change as more than the weather becoming warmer. Some discussion was placed on the weather and how it was becoming unpredictable. In the past, Dene elders could predict the weather, but this is no longer the case. Warmer temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, although seasonal and spatially variable, cause concern for animal migrations, in particular the lack of snow causing caribou to wander all over the place whereas in the past they would break trail for each other and stay together. There is a Dene legend about people in the past who were able to control the weather. These people would predict the weather. They could tell what was going to come before it happened by watching the color of the sky and connecting this to cloud patterns. Not many people can predict weather anymore.

Holism of ecosystems means all Dene, elders and youth, working together equally. When Dene talk about trees, they talk as well about porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) and fish. It is important to understand Dene concern for the overall health and faith all Dene have for the land. They are not as confident today with the natural environment. It is being changed by anthropogenic development far removed from Denendeh. Adapting to these impacts will depend, in part, on strengthening Dene teachings and traditional knowledge in order to provide a solid cultural foundation for actions that are taken. In this way, adaptations and other responses can be developed that are consistent with Dene cultural values but that may draw upon other resources such as outside technology.

Proceedings of the workshops have been produced which summarize the discussions and outcomes of the meetings. To protect the interests of the Dene, the detailed content of these reports is protected and cannot be reviewed or used without the full, involved, and meaningful consent of the Dene. In addition, Dene Nation has developed a web page summarizing the key findings of the DEWG. Digital photos and audio recordings, in each of the languages spoken during the meeting, were also collected and are housed in the resource center/archives of Dene Nation. The Dene want both to share and protect their knowledge. At the first workshop the working group asked that a book be written. Each region and each person is writing a chapter in this book on Dene observations and knowledge of climate change. Each meeting brings out something different from what is going on and what collectively is the traditional knowledge and practical projects the Dene are engaged in. Much is being learned from Dene elders, but it is often not written, as this is not how it has traditionally been conveyed, learned, and taught. An important issue raised was how intellectual property rights work and that knowledge holders had rights that had to be respected. Guests and observers to the workshops were asked not to present information verbatim, as expert testimony, and for profit. The ownership of traditional knowledge and stories, the benefits accrued by appropriating the voices or representations made without permission is a serious consideration. Once written, the form of knowledge that is conveyed is the lowest (crudest) level of understanding. Dene oral tradition and practice is the authority and so even what is written here is only one telling of the climate change story.

Regional technical staff spoke about changes in climate, and causes and responses to these changes, including traditional knowledge and stories passed down from their relatives. Dene have always been able to adapt to change. For example, Gwich’in learned to cope with and understand change. In the Sahtú, the people lived off the land for generations, and many recalled parents and grandparents teaching how the climate was changing and that the sun had changed the most. The strength of the moon was observed to be "not as bright" as it was in the past.

Dene demonstrate extensive knowledge about climate change in their daily lives and during the workshop a small amount was documented. This was done to share Dene views and observations among regions and at the international level. Dene knowledge is shared to educate non-Dene. There is significant concern that traditional knowledge, observations, and activities on the land be made apparent to Canadians and to the international community so that what is known can be improved, so that better decisions can be made.

All the problems are man-made. We have to make a lot of noise to be heard. There’s some places down south you can’t even go fishing but we can still go fishing up here. All the stuff going into the water from down south is coming up here. We need to put the fire out at the source. We can’t forget our traditional knowledge and to use our Elders. I want our children a hundred years from now to say "My god, they did a good job!" —Leo Norwegian, Liidlii Kue, Denendeh, March 13, 2003

3.1. Introduction (Denendeh: the Dene Nations Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Denendeh: the Dene Nations Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study)

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Denendeh: the Dene Nations Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group climate change case study. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Denendeh:_the_Dene_Nation’s_Denendeh_Environmental_Working_Group_climate_change_case_study- ↑ Brown, J. and E.Vibert (eds.), 1996. Reading beyond Words: Contexts for Native History. Broadview Press, xxvii + 519p.– Krech, S. III, 1999.The Ecological Indian: Myth and History.W.W. Norton, 318p.

- ↑ Erasmus, B., C.J. Paci and S. Irlbacher Fox, 2003. History and Development of the Dene Nation. Indigenous Nations Studies Journal, 4(2).–Watkins, M. (ed.), 1977. Dene Nation:The Colony Within. University of Toronto Press, xii + 189p.

- ↑ Dene Nation, 1984. Denendeh: a Dene celebration. Dene National Office, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, 144p.

- ↑ Dick, L., 2001. Muskox Land: Ellesmere Island in the Age of Contact. University of Calgary Press, xxv + 615p.

- ↑ Brown, L.R., C. Flavin, H. French, J. Abramovitz, S. Dunn, G. Gardner, A. Mattoon, A. Platt McGinn, M. O’Meara, M. Renner, C. Bright, S. Postel, B. Halweil and L. Starke (eds.), 2000. State of the World 2000: A Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society. W.W. Norton, ix + 276p.

- ↑ Dene Nation, 2002. The Denendeh Environmental Working Group: Climate Change Workshop.–Dene Nation, 2003. <a href="http://www.denenation.com" rel="nofollow" title="http://www.denenation.com">Report of the Second Denendeh Environmental Working Group: Climate Change and Forests Workshop</a>.–Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., Association, Kitikmeot Inuit, and Canada, Indian and Northern Affairs, 2001. Elders’ Conference on Climate Change, Cambridge Bay 2001, March 29–31.Workshop report, 92p.

- ↑ Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.

- ↑ Dene Nation, 1999. TK for Dummies: The Dene Nation Guide to Traditional Knowledge. Dene National Office, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, 13p.

- ↑ Dene Nation, 2003. Report of the Second Denendeh Environmental Working Group: Climate Change and Forests Workshop.