One Lifeboat: Chapter 3

Case Studies

Contents

- 1 Case Study 1 – International Market Supply Chains

- 2 Case Study 2 – Trade in Illegally Produced, Harvested or Transported Materials

- 2.1 China as a Consumer of Illegally Caught Wildlife and Products

- 2.2 Ozone-depleting Substances (ODS)

- 2.3 Conclusions on Eliminating Illegal Activities Even where mature international agreements, such as CITES (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) , are in place, it has proved to be very difficult to eliminate all the important abuses. On some problems, such as the import of elephant ivory, there has been great progress. But many of the world’s wildlife species and plants remain at high risk and with the expanding wealth in China and some other countries, the situation could get worse. Clearly there needs to be even more international cooperation, including stepped-up surveillance and enforcement for this form of trade to be stopped. But it is also a matter of public education and behavioural change that is needed within China. As long as there is a high level of demand, smuggling and other illegal acts will take place.

- 3 Case Study 3 – Biosecurity and Biodiversity Protection

- 3.1 Animal to Human Disease Transmission and Epidemics

- 3.2 Safety, Quality and Competitiveness of Food Supply Chains

- 3.3 Existence Value of Protected Areas and Species in China

- 3.4 Climate Change, Human Activity and Biodiversity

- 3.5 Conclusions about Biosecurity and Biodiversity Conservation Although China is investing considerable effort in dealing with these topics, it is difficult to be highly optimistic about outcomes over the short run. China’s situation is of interest to the world for reasons of both public health and conservation. The two interests are intersecting to a greater extent than ever before, but they are also coming up against entrenched economic interests as well as the problems of dealing with rural poverty. While it is possible to take steps such as setting areas off limit, carrying out culls and prohibiting the sale of wildlife for food or for other uses, it is quite another matter to create an effective enforcement approach. A large part of China’s problems with biodiversity (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) protection can be linked to trade. It has been difficult to make CITES work well, and the rapid rise in imports and exports has created problems of invasive species (Alien species). In the future, domestic and international tourism to China may create additional problems (although also certain opportunities) for biodiversity protection.

- 4 Case Study 4 – Regional Environmental Impacts – River and Marine Water Issues

- 4.1 Land-based Sources of Marine Pollution

- 4.2 River Outflow

- 4.3 Coastal Inputs

- 4.4 Marine Impacts of River and Coastal Inputs of Pollutants

- 4.5 Shared River Basins

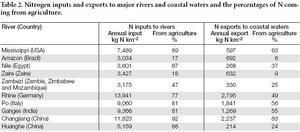

- 4.6 Conclusions about China’s Regional Transboundary Water Issues The future of China’s relations with its bordering neighbours will certainly be more focused on environmental matters than in the past. There are various mechanisms by which this may happen, but the institutional framework for regional environmental protection is still very weak—lagging behind both the need, and also the level of sophistication that might be expected of such relationships today. The mix of pollutants and the varied sources also present a major problem. Cleaning up industrial and urban sewage will help, but the prime problems are related to agriculture (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) and, to some extent, aquaculture. In addition, the pollution-loading of [[river]s] and coastal waters will be affected by airborne sources, including cars and trucks. Given the continued rapid economic development within China, downstream and coastal impacts seem likely to worsen over the short term. Specifically, most of the environmental actions taken under the 11th Five-Year Plan will not have a great deal of impact on the main cause of TBP, which is agriculture. Without additional actions to control water (Water pollution) pollution from the overuse of chemical [[fertilizer]s] for crop production and poor livestock management, the discharges of N and P into coastal waters will rise.

- 5 Case Study 5 – Learning From and Sharing Environmental Experience

- 5.1 Advice and Assistance to China

- 5.2 CCICED – A Unique Policy Advisory Body

- 5.3 Improving China’s Capacity for Environment and Development

- 5.4 China’s Development Cooperation with Africa

- 5.5 Conclusions about China’s International Learning and Sharing China has a 35-year record of exchange of views on environment and development with the international community. It has demonstrated an ability to take on board radical new ideas as part of its overall opening up to the world. The characteristics of this learning include the following features:a clear idea of what is wanted/needed, and from whom China can learn;adaptation to Chinese context and needs through experimentation;an experimental approach to policy: “feeling the stones in crossing the river”;effectiveness in scaling up successful programs;careful sequencing; andopenness to dialogue. The task is made easier by the reality that China can pick and choose its sources. China has dealt with the huge supply of expertise available from governments; international organizations and NGOs; business consultancies and multinational firms; and others, in a very strategic and considered way, identifying which organizations they want to work with on which issues, based on comparative strengths and capacities but always keeping China’s own needs and priorities front and centre. Yet, while China has been very good at learning from, adapting and incorporating international best-practice, at the same time the Chinese have been somewhat weaker at learning from their own experience: they have not developed and systematically applied good methodologies for analysis and evaluation of their own policies. This is an area that needs to be strengthened. Perhaps most difficult has been the capacity to develop a comprehensive and effective approach to the use of economic incentives for matters such as industrial pollution control and for enhancing resource use and energy efficiency. China also has found useful ways to draw on international expertise, for example via the CCICED. And only weeks after the release of the report to the British Government by Sir Nicholas Stern on economic aspects of climate change (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) ,[73] he travelled to China to meet with senior policy-makers. To say that China is broadly engaged with the international community as it plans and implements its domestic environment agenda is an understatement. What will become more apparent in the years ahead is a growing influence on the part of China within global fora.

- 6 Notes This is a chapter from One Lifeboat: China and the World's Environment and Development (e-book). Previous: Chapter 2: China's Growth and Consequences (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) |Table of Contents|Next: Chapter 4: Ten Issues (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3)

Case Study 1 – International Market Supply Chains

Agricultural Products

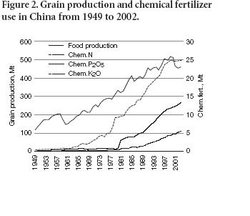

One of the most relevant issues in terms of global impacts of the Chinese economy is the question of whether China will continue its former policy of self sufficiency in grain supplies. Two aspects are of particular interest in this regard:

- China’s grain harvests declined between 1998 and 2005 by nine per cent, or 34 million tons. Falling water tables, the conversion of agricultural land to non-farm uses (Land-use), such as urbanization, and the loss of farm labour in rapidly industrializing provinces are at the source of this loss. Rice productivity, in particular, has been attributed to water shortages.[1] A study by a joint U.K./Chinese team released by U.K.’s Environment Minister Elliott Morley in 2004 has shown that Chinese staple crops— rice, wheat and maize—may fall by as much as 37 per cent by the end of the century, under current climate change projections.[2]

- Food consumption levels have been increasing with China’s growth and will undoubtedly continue growing with the increasing wealth of the average citizen. As a consequence, the demand for meat, fish, vegetable oils and diary products will rise as well, which in turn requires additional quantities of grain for feed. China produces nearly half of the world’s pork, is the world’s second largest poultry and the third largest beef producer.[3] China already imports bulk commodities for its labour-intensive food industry. China is a major exporter of manufactured foods, animal products, fish, vegetables and fruit, mainly aimed at Asian markets. Although China’s demand for protein may be supplied largely by domestic producers of livestock, those farms increasingly will rely on imported corn, soybeans and soy meal for feed.

Soybean and oil palm production in the tropics is of particular environmental concern because of the massive land conversion of tropical forests that this often entails. Plantations of these two crops already cover an area of the size of France and more forest is being cleared for this purpose every year. From 1993 to 2002, the global harvest of soybeans increased from 115 million tons to 180 million tons. Although productivity per area was also improved through new varieties, the cultivated area in Argentina and Brazil increased dramatically, at the expense of the natural savannah (Cerrado) and Amazonian forest. The recent increase of the rate of deforestation in the Amazon is mainly related to cattle ranching and soy plantations. By far the largest importers of soybeans from South America in 2001 were Europe (45 per cent) and China (35 per cent).

The area under oil palm plantations has increased between 1990 and 2002 by 43 per cent to 10.7 million hectares (ha). A vast new oil palm development project in the highlands of Borneo, straddling the border between Malaysia and Indonesia has drawn negative reactions the world over.[4] The area is still largely covered with primary forest and inhabited by indigenous peoples. Forest clearing for oil palm major loss of some of the most diverse natural habitat in Borneo. A recent study [5] has identified investors possibly involved in this completely unsustainable development would, because of the rugged up-land terrain, lead to massive erosion and low yields, besides undertaking, including the China Development Bank and the CITIC Group of China. At the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) in March 2006, the three governments sharing Borneo— Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei—made declarations in support of conservation efforts in the “Heart of Borneo.”

A new threat to the remaining natural [[forest]s] of Southeast Asia, are various plans for biodiesel from palm oil. Indonesia has announced the conversion of six million ha of lands for this purpose. The lands are supposed to be from land not in primary forest, but the track record in Indonesia has been illicit burning of natural forest for this purpose. While much of the biodiesel will be for domestic use, it would be very surprising if there were not willing importers, including China, which is promoting demand for biofuels, including ethanol and biodiesel, but will have a difficult time meeting this demand if it relies solely on its own sources.

Agricultural Products Synthesis

Clearly, China cannot be held accountable for unsustainable agricultural practices abroad. The fact that rising Chinese demand for agricultural produce has led to a price surge for certain commodities, thus creating incentives for uncontrolled agricultural expansion, is primarily related to weak land use governance in producer countries. It is in accordance with its WTO membership that China lowers tariffs, weakens state monopolies and increases the openness of import allocations, thus weakening the policy instruments the government has been using to restrain agricultural imports. However, as some authors [6] have stressed, if China turns increasingly to the world markets for massive imports of grain and other agricultural products, this has the potential to change the geopolitical situation, increasing the insecurity for sustainable supplies, and exposing China to worldwide attention and criticism simply because of the dimensions of China’s demand. Already today, large scars of deforested areas in the Amazonian states of Mato Grosso and Rondonia in Brazil that can be attributed to soybean plantations and are clearly visible by satellite. It will therefore be necessary that China articulates its agricultural and investment policies, ensures reliable statistical information to accurately assess its development and participates in international fora to assess the impacts of markets on biodiversity and the natural resource base.

Forest Products

A considerable number of studies have been undertaken as a consequence of the rapidly increasing Chinese demand for forest products, particularly after the introduction of the National Forest Protection Program in 1998, which banned logging in ecologically-sensitive areas of China. These have been initiated by Forest Trends, the Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy (CCAP) the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), WWF International and their numerous partners in China. Although there remain uncertainties with regard to unreported logging as well as import and export statistics, the level of understanding of China’s forest products’ market is more complete than for other resources.

The per capita use of wood products in China currently is modest. The average person in the U.S. uses 17 times and an average Japanese six times as much wood as a person in China! In 2003, China consumed about 173 million cubic metres of wood for its domestic use and for export. Of this volume, only about 79 million cubic metres log volume was produced by China’s own forests and plantations. This figure includes the industrial timber as well as fuel wood according to national statistics, plus an estimate of undeclared industrial production. The State Forest Administration has recently estimated the amount of unreported logging to be as high as 75 million cubic metres per year. [7] Domestic need for wood required 138 million cubic metres, and 35 million cubic metres were used to manufacture wood products for export to other countries.[8] In some instances, Chinese firms are able to take what is waste wood and re-process it into first grade material. This is apparently the case for some low-grade yellow cedar obtained from British Columbia, reprocessed, and then sold to Japan as high quality product—China’s low labour cost advantage.

Rapid Growth of Timber Imports

In terms of size China’s wood market—including industrial timber, pulp and paper—is now the second largest in the world, after the massive U.S. market. To cover its demand, China has imported a rapidly increasing amount of wood. From 1997 to 2005 China’s total forest imports in volume (round wood equivalents – RWE) more than tripled from 40 million cubic metres to 134 million cubic metres.[9] The increasing demand for timber imports can, at least partly, be traced back to the logging ban introduced in 1998 under the National Forest Protection Program (NFPP). However, the decline in China’s own production began already prior to the introduction of the logging ban and is a consequence of the depletion of natural forests over past decades.[10] In response to the reduced production capacity of natural forests and the increasing demand for wood, China doubled its timber plantations from 14 per cent of the total forest area to 28 per cent in the 1990s. China has now the largest area devoted to timber plantations of any country in the world.[11] The Chinese plywood industry increased its capacity dramatically in the past 10 years (plywood production increased from 2.6 million cubic metres to 21.0 million cubic metres), which partly explains why China imports much larger quantities of raw logs today.

Origin of Imports

China’s three largest suppliers of timber in 2003 were Russia, Indonesia and Malaysia, followed by New Zealand, Thailand, the U.S., Papua New Guinea and Myanmar. These trade statistics show that most of China’s timber imports originate from countries where the forest estate is in decline and/or where forest governance is weak.

Russian Federation

In terms of volume, the most important timber supplier is the Russian Federation, with 21 million cubic metres of logs and wood-based products exported to China in 2003.[12] The aggregate demands for wood products from Japan, South Korea and China have led to serious over-logging in the southern part of the Russian Far East and Eastern Siberia with irreparable damage in logged permafrost areas, and forest fires.[13]

Indonesia

China’s imports from Indonesia increased gradually to reach about three million cubic metres RWE in 2003. China also imports a more rapidly increasing amount of pulp and paper from Indonesia, which reached eight million cubic metres RWE in 2002. The Indonesian pulp and paper industry has a significant overcapacity that outpaces the supply of sustainably harvested timber. The demand of the Indonesian pulp and paper industry, which consumes about 20 million cubic metres of round wood, is a major cause for illegal harvesting practices from natural forests.[14] The official Indonesian export statistics record a significantly lower volume of timber exported to China (20 per cent less in 2002), than recorded in China’s import statistics.[15] However, the extent to which Chinese timber imports from Indonesia are from illegal sources is open to debate and requires further analysis and evaluation of current data.[16] In recent years, significant amounts of wood have moved illegally from West Papua.[17]

Malaysia

The official export statistics show only half the volume of timber imported by China from Malaysia. Some of the difference may be due to Malaysia’s free ports. On the other hand there is substantial evidence that large amounts of illegally cut timber are smuggled into Malaysia from Indonesia and re-exported to China.[18]

Increasing Timber Exports

In response to a rapidly growing demand for furniture, plywood, wood moldings and floorings, particularly in the U.S., Europe and Japan, China has in recent years become the world’s largest wood workshop. Between 1997 and 2005, the U.S. increased its imports of manufactured wood products from China by almost 1,000 per cent and reached 35 per cent of China’s total export value of timber products. Europe’s imports from China during this period also increased dramatically, by almost 800 per cent.[19] Indeed, a very large part of the timber imported by China is used to manufacture timber products for export. The exported volume corresponds to over 70 per cent of the timber imported by China. Much of the wood is made into furniture, and some interest on the part of furniture producers is developing for certification processes, via the Forest Stewardship Council, now active in China.

Future Trends

According to White et al, forest product imports by China are likely to double in the next 10 years, based on an assumed six to eight per cent growth of GDP.[20] One of their key findings suggests that the domestic as well as the export demand for manufactured wood products will continue to grow dramatically, at least over the medium term. The same authors emphasize that China, given its large export potential, may become increasingly vulnerable to consumer preferences, with growing environmental awareness. European countries are already drafting policies and implementing procurement procedures that require verification of legal or even independently certified origin of wood products.

Wood Product Synthesis

A number of policy recommendations have been made in the past to reduce the impact of China’s increasing demand for wood products, domestically and for export. These focus on the following aspects:

- Improving the productivity of the Chinese forestry sector to reduce its reliance on imports.

- Strengthening of China’s environmental protection initiatives, including through government incentives for farmers and local governments to protect and restore [[forest]s].

- Encouraging environmentally sound wood and fibre production and processing in China.

- Improving the efficiency of wood harvesting, distribution and use in China.

- Encouraging imports or purchases of wood produced legally and from well managed forests.

In light of the growing demand for timber products globally, including China’s massive manufacturing and export capacity, a number of policy recommendations are also addressed to a broader range of importing and exporting countries.[21] Those include recommendations on procurement policies; education programs for retailers and consumers; supply chain management and certification; bilateral cooperation on illegal logging and trade; updating forest legislation and enforcement; and the promotion of small-scale forest-related livelihood. It is quite possible that a sustainable pathway could be created by a range of Chinese and other national actions. However, it is perhaps equally possible that action will be far too slow to deal with issues such as rising international demands for cheap wood and furniture products, by the difficulties of various key timber exporting countries to control their own situation, and for Chinese domestic demand to rise dramatically, making it very difficult to put in place suitable sustainability strategies. As EU countries and others start implementing sustainable procurement policies, China likely will have to have systems in place to maintain access to such markets. Being ahead of the game may be essential if China wishes to secure a growing market presence.

Fisheries and Aquaculture

China accounted for about a third of the reported fish landings and production over the last decade, thus making it the world’s largest fish producing nation in the world. Its international trade in seafood soared from about US$1 billion to almost US$8 billion in a decade. China is the world’s largest seafood exporter, with more than two million tonnes exported at a value of US$5.5 billion in 2003.

It should be noted, however, that China’s aquaculture makes up a very sizable proportion of this production. The surge in seafood exports is related to the increased production of farmed seafood such as shrimp, scallops, eel, tilapia and crawfish.[22] Moreover, aquaculture benefits from the huge amounts of by-catch taken by Chinese fishing fleets, and used as feed. Due to its impressive processing capacity, which increased by 50 per cent between 1996 and 2000, China takes in for processing and re-export a large part of the globally landed value of fish. This has included species of considerable conservation concern such as Patagonian toothfish (also sold as Chilean Sea Bass) from Antarctic waters. The re-exported, semi-processed fish are sent to countries such as Canada for further processing and then sold in these countries, or exported again to the U.S. or other markets under the Western country brand name. This process works particularly well for white-fleshed fish that lose their species identity, ocean of capture, and place of processing. In such a situation it is very difficult to create a good chain of custody concerning any kind of reliable sustainability assertion or certification (e.g., by the Marine Stewardship Council).

Since the late 1980s, China’s own marine fishery resources have been overfished. This has been an issue the Chinese government has taken seriously. Very considerable resources have been devoted to research and the rational utilization of its marine resources. A significant number of Chinese fisheries scientists have assessed these stocks, e.g., Jin; Yuan and Cheng et al.[23] The “Fishery Act” of 1986 was subsequently amended by an “allowable catch quota” in 2000. A moratorium on summer fishing was already previously introduced in the Bohai and Yellow Seas and extended to all of the Chinese waters in 1998. A mandatory fishing vessel buy-back program was also introduced, albeit with modest success. With the widely used trawl nets and purse seiners bycatch is very substantial and it can be expected that fishing effort, dictated by the decreasing resource, will be greatly reduced in the coming decade.[24]

A number of fisheries scientists have reported problems with Chinese fisheries data, with implications at the level of global catch statistics. Watson and Pauly demonstrated that over reporting of catch by China (presumably to demonstrate production increases, which is important to local officials) led to substantial over reporting of marine fish catches, creating a false perception of good health in world fisheries.[25] An additional difficulty has been reported with the privatization of the previously state-owned marine fishing enterprises and the consequences of WTO accession: the fisheries statistics system has fallen apart. Current statistics on catch are incomplete and inaccurate, which does not allow China to monitor the sustainability of its fishery resources, and therefore with consequences for the world statistics.

China’s fisheries fleet did not venture much beyond its own EEZ until about 1985. Thereafter its activities began to expand, particularly around the turn of the century, and now span the world’s oceans. In some cases, China cooperates with other countries in patrols to monitor these offshore fisheries, for example with the U.S. and Russia concerning drift net fisheries in the North Pacific, and with Japan and Korea in waters closer to China.

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) has become a serious global problem and is a major obstacle to the achievement of sustainable world fisheries. IUU accounts for US$4 to 9 billion in value per year, or up to 30 per cent of the global marine catch. This loss is primarily borne by developing countries that provide over 50 per cent of all internationally [[trade]d] fish products.[26] An important element in IUU is the open registries or “Flags of Convenience (FOCs)” for large-scale fishing vessels. Countries that operate an FOC registry cannot guarantee “a genuine link” required under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) between states and those authorized to fly their flags. Consequently they cannot or will not take action against fishing boats damaging the marine environment or living marine resources. Effective flag state control is equally necessary to ensure safety of life at sea, shipping standards and securing the welfare of seafarers.

Over 1,200 large-scale fishing vessels were registered to FOC countries in 2005 and the large-scale fishing vessels on the Lloyd’s Register with flags listed as “unknown” has increased to 1,600 in 2004. This means that about 15 per cent of the world’s fleet of large-scale fishing vessels is flying FOCs or listed as “flag unknown.” A recent study[27] analyzed information available from the Lloyd’s Registry of Ships between 1999 and 2005 on fishing vessels registered to the top countries that operate FOCs. Belize, Honduras, Panama, St. Vincent and the Grenadines have topped the list of FOC countries, with the largest numbers of vessels registered to fly their flag.

Despite the fact that China is the most important fishing nation in the world, the use of FOCs by mainland Chinese companies does not seem to be common. In fact, China undertakes some fisheries patrols in international waters to police its own fleets. Among the countries where companies that own fishing vessels flagged to one of the FOC countries are based, one finds Taiwan with the largest number of vessels (142), as well as Hong Kong with 27 vessels. Members of the European Union are also frequent users of this dubious instrument which is commonly used to conceal illegal fishing.

Fisheries Synthesis

China is the country to reckon with now in world fisheries and aquaculture. It has achieved remarkable progress in terms of the range of products produced from the sea, much of which is consumed domestically. It has indicated serious intent to regulate its own fleets where they are operating within national and international waters. And it takes seriously the need for good knowledge to manage fisheries. However, the statistical information provided has sometimes been of limited value, or even counter to the real situation. Furthermore, China, by actively taking over a huge processing role for re-exported fish products, has probably further lowered the accountability of fisheries processors in other countries concerning the sustainability of their raw and semi-processed materials. Traceability appears to be difficult, at least for some common forms of seafoods such as white-fleshed fillets.

The High Seas Task Force (HSTF) on Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing [28] presents a comprehensive menu of proposals to improve prospects for monitoring and action to improve the situation in world fisheries. China has not been a member of this Task Force, and is not at the present time committed to implementing the proposals. Indeed, China, along with Japan and Korea, are not among the 52 members of the UN Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) that is the main guiding global governance beacon for sustainable fisheries. In light of China’s vital interest in a sustainable use of the marine resources of the world, for its own long-term supply security either based on marine catch or in support of the increasingly important aquaculture, the proposals of the High Seas Task Force (HSTF) as well as other forms of international cooperation on these issues should be given serious consideration by China.

Energy Resources

China is now the second largest energy consumer after the U.S. Already the largest producer and consumer of coal in the world, but now with rising demand for oil and gas, China is a key player in the world’s energy markets. In 2003, China overtook Japan as the second largest oil consumer in the world.

Oil Demand

China’s oil demand in 2004 stood at 6.5 million barrels per day and is projected to reach 14.2 million barrels per day by 2025. This would mean that imports would have to cover a net quantity of about 10.9 million barrels per day according to the EIA.[29] A lot of attention has been given to recent investments in foreign oil assets by Chinese companies. The China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) acquired oil concessions in Azerbaijan, Canada, Indonesia, Iraq, Iran, Kazakhstan, Sudan and Venezuela. The China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec) also bought oil assets in Iran (Yadavaran) and in Canada’s oil sands. The China National Offshore Corporation (CNOOC) purchased a stake in the Malacca Strait oilfield in Indonesia. However, these participations will only be able to cover a small fraction of China’s projected oil demand. The country will thus remain largely dependant on imports.

Natural Gas

With the increasing concerns of the Chinese leadership about its energy supplies and the environmental advantage of using natural gas, China has in the past years invested heavily in gas infrastructure. In 2004, only about three per cent of China’s energy demand could be covered by natural gas, which is projected to double by 2010. China has considerable reserves of natural gas, mainly in the western and northern provinces, estimated at 1.5 trillion cubic metres in 2005.[30] The development of these fields however requires the construction of pipelines over large distances to aliment the urban centres of the east. Imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) will primarily be used to convert existing oil-fired power plants in the southern part of the country. In Guangdong Province, six gas- fired power plants of 320 megawatt (MW) are currently being built and an import terminal near the city of Guangdong is being built by BP.

Coal

China as the largest consumer of coal in the world has recently stepped up its coal production. In 2003 it consumed 1.53 billion tons, corresponding to 28 per cent of the world consumption. Over the long run, the proportion of coal in the energy mix of China is expected to fall; however, in absolute terms, coal consumption is still projected to continue rising. Very large numbers of coal-fired power plants are under development. With the opening of China’s coal sector to foreign investment, the prospects for investment in new, and environmentally more friendly technologies has been rising. Of particular interest to Chinese authorities is the potential of coal liquefaction technology, with recent U.S. cooperation established. [31]

Electricity

The early part of the new millennium saw a shortage of electricity supplies (estimated at 30 gigawatt (GW) in 2004). As a consequence of the shortage, the Chinese government has approved a large number of new power projects. Nuclear power generation increased from two GW to 15 GW between 2002 and 2005. An April 2006 deal with Australia to supply 20,000 tons of uranium per year should allow China to develop its nuclear capacity by adding 27 GW by 2020, and thereby quadruple the nuclear part in the energy mix (currently 2.2 per cent) China is committing US$1 billion and the efforts of 1,000 Chinese scientists to the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) located in France in the interest of building advanced science and technology capabilities for environmental protection and securing new energy sources.[32] Wind power and solar power also are being added. China’s electricity consumption is expected to grow by an average 4.3 per cent annually for the next 20 years.[33]

Biofuels

China is number three in the world after Brazil and the U.S. in terms of ethanol for fuel production. Plans are for vast increases in ethanol-gasoline mixes. The four state-owned grain-based ethanol makers—China Resources Alcohol, Henan Tianguan Group, Jilin Fuel Ethanol and Anhui Fengyuan Group—together produced 720,000 tons of fuel a year in 2004 and planned to increase production to more than one million tons by the end of 2005.[34] China Resources Alcohol may build a 600 million yuan plant in Guangxi Province to distill alcohol from cassava and molasses. The biofuel capacity increase comes in response to a government direction in 2004 addressed to five provinces to include 10 per cent ethanol in their car fuel. Now such fuel mixes are available in nine provinces. The longer-term goal is for biofuel to become 10 per cent of all fuels by 2010 and 16 per cent by 2020.[35] This would mean increasing China’s ethanol production by about 15 times by 2020, to a level equal to the U.S. or Brazil’s current production.

China already has experienced shortages in ethanol, which raises a longer-term issue of whether ethanol might be imported, for example from Brazil. Ethanol will become a commodity on world markets, with important implications for sustainable land use in countries like Brazil. Similarly, palm oil plantations in Southeast Asia may become sources of biodiesel, possibly at the expense of the remaining rainforests in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. It is also possible that China and EU countries will compete for any available tropical country-produced biodiesel, perhaps including sources from Africa. The EU is now discussing sustainability certification of biofuel imports, an approach that China could also consider. There are various points of view about the use of food crops—such as corn—for fuel, including environmental and net energy gain considerations. What is clear for countries such as China, the U.S. and Brazil is that there are two prime values—fuel security, and local rural benefits. Already, the strong stimulus of this new sector is on the price of several commodities, including wheat, corn and soy, which China purchases on international markets.[36]

Energy Resources Synthesis

Among various concerns about the impact of China’s growth on the world’s market and the global environment, its rapidly increasing energy needs probably rank highest. There exist many legitimate reasons to take these concerns seriously: China’s energy needs are not only of geopolitical relevance in terms of the increasing competition over access to these resources, but also for the inflationary prices, and the security aspects that are related to it. They are equally relevant in relation to the rapidly increasing concerns over the climate change impacts of China’s massive fossil fuel consumption. Moreover, it is in China’s own best interest to reduce its dependence on foreign energy resources in order to guarantee a predictable development path, as envisaged by the Chinese leadership.

The conversion of energy generating systems to new environmentally beneficial technologies; the aggressive promotion of renewable energy; and much higher energy efficiency standards in all sectors of energy consumption, including building standards and low energy transport systems, are probably the areas that could be of greatest benefit to China. Unlike other markets with global impact, such as the import of commodities from countries with insufficient natural resource management, the energy future of the country is largely in China’s own hands. Energy production and consumption can be influenced to benefit the future of its own society in parallel with a reduction of the countries dependence from foreign resources as well as a reduction of negative impacts on the global ecology. Incentives; investment; pricing; regulation and enforcement; training and education for energy conservation, and for building advanced scientific capabilities for environment and energy conservation will contribute to a sustainable energy future for China. Clearly, however, the problems of China’s energy security also involve a great deal of cooperation from abroad to ensure that new technologies are made accessible in a timely way, and on reasonable terms, and to ensure that energy demands of other nations do not make it impossible for China to meet its legitimate and growing needs.

Metals

Although China currently accounts only for about four per cent of global GDP, its metal consumption is disproportionately larger, with 16 per cent of the world’s consumption. China is the largest consumer of copper, iron ore, steel, tin and zinc; the second largest consumer of aluminum and lead; the third largest consumer of nickel; and the fourth largest consumer of gold. China’s iron ore imports between 1990 and 2003 increased by a factor of 10. The country now consumes 35 per cent of the world’s iron ore. It produces more steel than the U.S. and Japan combined.

China depends on minerals imports which reached US$140 billion in 2004. However, China has large reserves of some minerals: 54 per cent of the world’s manganese reserves; 23 per cent of the lead reserves; 22 per cent of silver reserves; 12 per cent of coal reserves; 11 per cent of vanadium reserves; and six per cent of copper reserves.[37]

Nevertheless, commodity prices have risen to historical peaks, as global mining efforts cannot keep up with the demand of Chinese mills, building sites and car factories. According to Lin Hai, a manager at Guotai Asset Management, Chinese investment abroad has become a necessary step to ensure preemptive rights on raw materials and to keep costs low. The competition for Australian mineral resources is particularly fierce between Chinese companies, the South Korean steel maker Posco, and the Japanese companies Nippon Steel and Mitsubishi. Henry Wang from the Australian government agency Invest Australia has been cited to state that from all Chinese iron ore imports, China currently has some kind of involvement in 25 per cent of the suppliers, and it intends to increase this to 50 per cent.[38]

The massive demand for steel caused a temporary doubling of prices which peaked in 2004 at US$700 a ton, but prices have come down again since then. This has been seen as a consequence of stepped up steel production from Chinese producers and government efforts to slow down the real estate and construction industries. Construction accounts for 67 per cent of steel consumption according to Baosteel, the biggest Chinese steel producer.[39] With the increasing steel production in China (forecasted to reach 348 million tons in 2006), the country may soon become a net exporter of steel which would mark a drastic turnaround from the situation in 2004 when was the biggest steel importer!

This transformation is deeply troubling to the U.S. steel industry. In July 2006, the American Iron and Steel Institute released a report called The China Syndrome: How Subsidies and Government Intervention Created The World’s Largest Steel Industry.[40] It marked the start of a campaign to place tariffs on Chinese steel entering the U.S. on the grounds of subsidized production, worker conditions and poor environmental controls. In effect, the charge is that the U.S. industry is imperiled and 30 years of investment in environmental quality improvement will be lost in favour of low cost, unsustainably-produced steel imports.

Metals Synthesis

China’s consumption of metals is more directly related to construction of infrastructure than is the case with natural resources and even fossil resources. The surge of imports and the massive increase of China’s own production are largely driven by the country’s rapid urbanization. As urbanization is projected to continue over the next 15 years or more, and may reach a level where 55 or even 60 per cent of the Chinese population will live in cities, a sustained high level of metals consumption will exist. China will undoubtedly try to cover this demand increasingly from its own production and participation in overseas operations.

Unlike natural resources (particularly timber or fisheries products) the origin and conditions of exploitation of mineral resources are more easily verifiable, and are thus less prone to illegal exploitation practices. Although China’s huge consumption of metals may cause price reverberations on the world market, its impact on the global environment, biodiversity conservation and regional development prospects in other parts of the world is less severe than is the case with natural and fossil resources. It is also less evident, how efficiency gains could contribute to lower consumption levels by comparison to the case with fossil resources.

Recycled Materials

China is driving the waste trade in the world.[41] China’s imports of paper, scrap metals, plastics, electronics and other materials are leading to significant increases in the proportion of materials re-used in the world, and are relieving the burden of local jurisdictions and industries facing demands for increased recycling. Even some of the steel from the ill-fated New York World Trade Center was sent to China for recycling. This willingness by Chinese industry to purchase recycled material is a benefit for the world, and a means for China both to generate employment and to meet shortfalls in raw material for manufacturing. But it comes with a cost.

Some of the trade is illegal under China’s own laws, and some of the exported material to China, for example, electronic waste from the U.S., would not be allowed from countries that have ratified the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal. The problems of computer disassembly are considerable, with a limited number of small towns in China being converted into hazardous waste sites.[42] It has been suggested that most of the world’s “high-tech trash” ends up in China, despite official bans. A recent case involved some 27 companies in eastern Canada that sent computer components in some 50 shipping containers destined to China. The amount of plastic and metal waste totalled more than 500,000 killogram (kg). These were seized at the Port of Vancouver. The companies were fined only a nominal amount by Canadian authorities and their names were not made public.[43]

There are questions raised about the sanitation of some materials such as plastic bottles sent to China. And there are problems in China and elsewhere with ship-breaking, which involves many hazardous materials such as asbestos and heavy metals in electronics.[44] China has been cautious about some forms of recycled materials, for example textiles. This is a topic of active discussion on the part of the Bureau of International Recycling (BIR) which in May 2006 held its World Recycling Convention in China for the first time.[45]

Recycled Materials Synthesis

China is experiencing the same double digit growth in a great variety of recycled materials that it has seen for other resources. There are benefits to poor people by providing employment in China, and also to the very rich. It is said that the richest woman in China made her fortune by importing and reprocessing waste paper, developing new supply lines, and taking advantage of low cost shipping provided by empty container ships on their return voyages. Recycling has been a means to expand sources of supply for vital commodities, meaning less pressure on [[forest]s] and landscapes, and perhaps lower energy costs. It is a means for China to extend its concept of circular economy to a global level.

It is quite likely that China can lay claim to being the world leader in the import of recycled material. In addition, given its growing resource demands and focus on a circular economy, China should have a clear and direct interest in ensuring the “recyclability” of the products it produces. Environmentally smart product design and production also could help ensure Chinese access to increasingly sensitive international markets defined increasingly by “responsible producer” laws as well as by the European Union WEEE and ROHS regulations now coming into effect for e-waste products. Five or ten years from now will China have the advanced environmental technologies to ensure that it carries out recycling in the safest, most efficient and effective ways? If so, the world, as well as China, will have benefited immensely.

Some General Conclusions about China’s Market Supply Chains

Market supply chains have various junctions where important interventions could take place in order to promote sustainable consumption, production and trade. Certainly China, in its remarkably varied and very dynamic international relationships, is already starting to re-shape conventional thinking about market economics. It could do so in relation to sustainability concerns as well, and indeed, is doing so in relation to at least some forms of recycled material imports. Much more work needs to be done in order to understand the opportunities and sustainable development needs concerning China’s market supply chains. This is a relatively unexplored topic at the leading edge of environment, trade and investment. Below, a number of conclusions, organized around five main points, are offered on this subject:

1. China is a major commodity transformer.

- China has rapidly become the world’s largest consumer and producer of many different commodities.

- For a number of commodities, China has made a rapid transition from being a leading net importer to becoming a net exporter, often via value-added finished products.

- China’s own consumption often does not entirely explain the increased resource demand. In the case of certain commodities (timber, some fish) China could more appropriately be seen as the “world’s workshop” as opposed to the nation that uses up the world’s resources.

- Although China has an unmatched growth in terms of speed and duration, resource use is surging in many other parts of the world. Therefore its comparative advantage is a dynamic matter, and so are issues such as source and substitution potentials of raw materials.

- A very large part of the biocapacity of China, domestic or imported, is consumed by end-users in Europe and the U.S.

2. China’s domestic consumption is growing relatively slowly, although that may well change.

- The per capita footprint of the Chinese population is still relatively modest, even compared to some other Asian nations. It is the speed of development and the size of its population that create the concerns.

- China’s rapid urbanization and changing lifestyles of the urban population drive most of the domestic consumption issues.

3. Rapid growth in natural resource demand makes regulation of supply chains difficult.

- Concerns over China’s natural and fossil fuel resources use are much more prominent than concerns over the consumption of metals or other geological resources.

- High demand for natural resources is increasing illegal activities in countries of origin with weak governance systems, or in the global commons.

- Supply chain analysis, declaration of origin, certification and labelling can mitigate this difficulty and will become important aspects for consumers in China’s client countries.

- The responsibility of countries exporting to China and to consumer nations importing from China to take environmentally appropriate action cannot be overstated.

4. China has undertaken some very responsible sustainable development actions in dealing with international supply chains.

- Efforts of the Chinese leadership to show responsibility for global resource use and the environment (e.g., fuel efficiency standards) are always noted and well perceived in other countries.

- Self-sufficiency in terms of resource use, when justified on an economic and environmental basis, should remain a principle, but needs thorough, ongoing analysis.

- Resource and energy efficiency gains and a recycling economy are not only in the best interests of China itself, but also are the most effective measures to reduce global impacts.

- Perhaps the single most promising focus for alleviating China’s global environmental impact is through the adoption and promotion of new, resource-efficient energy technologies that also reduce China’s CO2 emissions.

- Close involvement in and cooperation with international conventions (e.g., UNFCCC, CBD, CITES, UNCLOS, Fish Stocks and other marine agreements) as well as with international NGOs can increase transparency and confidence, and lead to policy change.

- International cooperation (whether in the form of international commodity agreements, multilateral environmental or trade agreements, or “public-private supply chain initiatives”) offer key opportunities for improving the transparency and predictability of trade impacts.

5. International cooperation and improved Chinese research on environment and sustainable development implications of market supply chains are needed.

- Many authors regret the decreasing quality of statistical information from China, following privatization in many sectors. The general lack of high quality data does not help to support China’s case of improved efforts towards a satisfactory sustainable consumption, production and trade relationships.

- Similarly, there is a great need for improved scientific and impact information regarding the extent and severity of China’s external impacts arising from market supply chains and related problems such as long distance transport of pollutants generated in China to other countries and continents, and from other impacts such as inadvertent export of invasive species through trade.

In summary, China does have a responsibility, by virtue of its importance and growing power over international supply chains, for ensuring that production is done sustainably. A sustainable view of China in the world needs to be built on more than measures adopted within its own jurisdiction. There is a special opportunity and obligation for China, in cooperation with others, to play a special role in guiding international supply chains towards sustainable practices. Indeed, it would be surprising if, in the future, the world was not looking to China for guidance on governance for international supply chains.

Case Study 2 – Trade in Illegally Produced, Harvested or Transported Materials

This subject has been introduced in sections dealing with forest products, fisheries and recycling of e-wastes, but it merits additional attention, since some of China’s impacts are very substantial, and have been of concern for many years, and especially with increasing purchasing power within China. It also is important to recognize that progress has been made through concerted efforts on the part of both China and the international community on certain concerns, for example in ivory trade and on CFCs. Also, it is important to recognize the substantial number of international agreements that cover various illegally traded materials.

These international agreements include: the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES); The Framework Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety; the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer covering CFCs; the Basel Convention, which covers movement of toxic materials; various WTO agreements; FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) Responsible Fisheries and other regional or global fisheries agreements; and phytosanitary and sanitary measures, including those designed to reduce risks associated with spreading of infectious diseases. Bioterrorism issues are also part of the picture, although this subject is not covered.

China as a Consumer of Illegally Caught Wildlife and Products

China is the largest market for illegal trade in wildlife from Southeast Asia, and also a major market from other countries such as Russia, Mongolia and India. Animals traded include snakes, pangolins, lizards, birds and turtles as well as endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) animals such as tigers, leopards, bears and wild ox. According to a study by Chinese scholars, the increased trading activity between China and Vietnam has led to the development of a trading network involving some Chinese provinces, Vietnam, some other Southeast Asian nations, Hong Kong and Macau. Wildlife from Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam is first transported to border cities in Vietnam. The wildlife is then taken to the purchase stations in the Chinese border areas and then redirected throughout the country. The insatiable demand for wildlife and products in China has caused detrimental effects in those supplying countries.

China’s consumption of global wildlife has literally pushed the conservation efforts of many supplier countries into total crisis. The trade in tiger and leopard skins, bones and parts from the Indian sub-continent into Tibet and thence down to Sichuan and other markets in China, is decimating tiger [[population]s] in those countries. The increased demand for antelope meat and horns (e.g., sable antelope) from Mongolia and Russia has caused a huge upsurge of poaching in those countries. The demand for reptiles and other wildlife products from the Indochina region has wiped out much of the wildlife.

The absence of an agreement regarding the sovereignty of the Spratly Islands, which are claimed by several ASEAN countries, leads to overexploitation of resources, and a complete lack of protection of those important marine environments. Entire coral reefs are dredged up and taken to Hainan for lime, while collectors of shells, pearls and rare grouper fish have decimated other reefs. The import of live tropical fish for ornamental fish trade or exotic foods is growing fast in Hong Kong and southern China, putting pressure on reefs throughout Indonesia and Philippines and leading to some terribly destructive collecting methods such as coral blasting and cyanide fishing.

There are mechanisms being designed internationally and domestically to handle these types of marine use problems. For example, there is a marine aquarium fish certification process. Hainan has struggled to develop as an eco-province dedicated to principles of sustainable development. And China indicates that where marine boundaries are still in dispute, resources will be used but in a sustainable way. China has been a prominent and active partner in the Global Environment Facility (GEF) sponsored program called PEMSEA (Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia).[46] For some activities, such as marine use zoning, and shipping port clean-up, there have been major successes within China through PEMSEA. But dealing with regional marine biodiversity protection is very difficult.

More could be done to improve transborder management of Protected Areas (PAs) and control of illegal wildlife trade routes especially on the borders China shares with Mongolia, Russia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Pakistan and North Korea.

Ozone-depleting Substances (ODS)

In 1999, the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA), the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation (MOFTEC) and the General Administration of Customs (GAC), jointly issued a circular on the Licensing of Ozone depleting Substances (ODS). The circular stipulates that SEPA and MOFTEC are responsible for registering companies engaging in Ozone depleting Substances (ODS) trade, and responsible for annual export and import quotas for all of China as well as individual companies. MOFTEC is also responsible for issuing ODS trade licenses, while GAC is responsible for giving clearance to Ozone depleting Substances (ODS) by licenses issued by MOFTEC. Also, China’s Country Program on Ozone depleting Substances (ODS) Phaseout has now considered the control of production and consumption of ODS through foreign direct investment.

In some ways, China’s efforts under the Montreal Protocol have been a model effort of international environmental cooperation. China has been permitted to produce and to import CFCs to 2010 as a developing country. It has been proactive in domestic efforts to produce CFC-free refrigerators, and to take other steps to eliminate use of Ozone depleting Substances (ODS). Licensing rules were established in 1999 by three Chinese government agencies concerning ODS trade, and controls exist for production and consumption of these substances in foreign direct investment activities within China. China has taken an earlier than required commitment date of 2007 for a halt in domestic production.

But the problem of illegal trade in ozone-depleting substances involving Chinese firms has been very difficult to solve. China set out a plan to control the “Three Illegals” (production, consumption and trade) in 2004. Still, operating apparently from only two ports, Shanghai and Ningbo, traders falsify documentation and send ODS shipments to more than a dozen countries. China is considered the main source of illegal CFCs in the world according to the EIA,[47] a position it has held since 1998. China has been the world’s largest producer and consumer of these substances. With the ending of ODS production, stockpiles in China should diminish rapidly. Yet there may well be contraband sources that could fuel continuation of this trade. Following the release of the recent EIA report, China at the 17th Montreal Protocol Meeting of the Parties “made a commitment to change their domestic export policy, take action against the smugglers and implement measures to put a stop to the black market operations.”

This example illustrates the difficulties faced in eliminating a global environmental scourge, even where there is strong national and international will backed up by considerable financial expenditures from both China and international sources. Part of the problem lies with the nature of the international agreement itself, related to both licensing and tracking arrangements. For example, large discrepancies exist between export numbers from China and ODS import numbers from Indonesia.

Conclusions on Eliminating Illegal Activities Even where mature international agreements, such as CITES (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) , are in place, it has proved to be very difficult to eliminate all the important abuses. On some problems, such as the import of elephant ivory, there has been great progress. But many of the world’s wildlife species and plants remain at high risk and with the expanding wealth in China and some other countries, the situation could get worse. Clearly there needs to be even more international cooperation, including stepped-up surveillance and enforcement for this form of trade to be stopped. But it is also a matter of public education and behavioural change that is needed within China. As long as there is a high level of demand, smuggling and other illegal acts will take place.

In the case of economic resource activities such as fisheries and timber trade, there are many opportunities for China to take more effective action under existing cooperative agreements signed with various nations such as the U.S. and Indonesia, and in the case of marine protection, through regional partnerships such as PEMSEA. It is also important that in establishing new arrangements, for example, with Latin American and African nations, and in the conduct of Chinese businesses abroad, that best practices and corporate social responsibility be exercised.

Porous borders, especially in western China, and the massive volume of trade make regulation difficult. China has tried to crack down on trade in [[endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered)] species], and on various other trade flows. The struggle to reduce and eventually eliminate ozone-depleting substances illustrates just how difficult it can be to stop a lucrative illegal activity—one that has ranked at the level of some illegal narcotics trade during the past decade. But China’s role has been quite exemplary, and this is one topic where there is some cause for applause. While victory is not complete, China deserves all the recognition that it has received for a massive effort of value to all countries. It would appear from this particular effort and from some others, that action to address a serious illegal problem will take at least 10 to 15 years for substantial progress to be made. In the case of CITES, it is an ongoing problem even after three decades of implementation. There is a need to reduce this time and to seek breakthroughs.

It is hard to avoid the reality that many of the activities branded illegal are in fact not well covered under existing international legally binding agreements, or occur in countries with weak governance and enforcement regimes. Thus self-regulation by Chinese authorities, accompanied by capacity development abroad may be the most sensible route. This can involve a range of measures from well-enforced bans on some materials and sources, to environmental and sustainability certification such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification.

Case Study 3 – Biosecurity and Biodiversity Protection

Over the past decade the world has grown smaller in many ways. One aspect is the ease with which biological problems seem to move from being local to becoming regional or even global concerns. These have many economic, health and food safety repercussions, and also affect natural ecosystems and biological diversity. The most recent example is avian influenza, which moves with ease from tropics to sub-Arctic regions and across great latitudinal distances, at least partly due to migratory waterfowl. The elaborate precautions necessary for food safety are becoming codified in drastic revisions to trade rules. Problems of alien invasive species are important for all importing and exporting nations, including China. Biodiversity protection is a matter closely aligned with climate change, and with tourism potential of nations. This case study surveys each of these topics, although not in great detail.

Animal to Human Disease Transmission and Epidemics

Zoonoses worldwide (“mad cow disease,” foot and mouth disease, swine fever, several tropical African fevers, schistosomiasis, etc.) demonstrate that disease routes between wildlife and man are of increasing significance. There is a need in China to better understand the potential pathways for infection. In addition to accurate mapping of routes and dates used by migrating birds and marine organisms, there should be a careful study of major trade routes of other wildlife products and foods and also maps of the major domestic animal trade patterns. Such basic data will prove valuable in accessing risk and also in planning controls in the event of further outbreaks of animal/human diseases.

Serious epidemics of two wildlife-related diseases, SARS and avian flu, in recent years—both accompanied by loss of human life as well as enormous financial losses due to restrictions on travel (SARS) and destruction of poultry—bring to prominence the ever-present dangers associated with movement of animals. Whether by natural migration or domestic trade, or through the dangers posed by close association between human beings and animals in conditions of less than satisfactory sanitation, the dangers are likely to be of increased concern within China and internationally. The continued, increasing demand for wildlife foods, the breeding of wildlife for foods or medicinal use, and the close association of domestic and wild animals all pose dangers to human health. The continuing losses of adequate natural [[forest]s], wetlands and grasslands increase the degree of interaction between domestic and wild animals and add to these risks.

The idea of culling wild waterfowl has been voiced in several countries including China. The idea has many drawbacks, including: wasteful and unnecessary destruction of valuable wildlife; culling leads to atypical and accelerating dispersal patterns by surviving birds which may hasten the spread of the disease; culling may also cause a local vacuum which accelerates the immigration of new wild [[population]s] into the culling area and may also increase rather than decrease the rate of spread of the disease. Most evidence of timing of spread and direction of spread indicates that, to date, wild bird migration has played only a small part in the distribution of the disease so it is better to concentrate on the major cause, which is human trade in poultry and rearing conditions that promote fast disease spread through domestic poultry populations.

The number of humans affected by avian flu remains low, transmission rates between humans seem zero to low, maybe because the disease tucks in deep in the lungs rather than in the nose and throat from where sneezes and coughs transmit most other flu viruses. The danger is seen that further mutation of the avian flu could render it a potential pandemic disease. Thus governments, including China, are spending considerable sums of money to prepare for the possibility of this particular problem going global. China and other Asian nations will face considerable pressure in the years ahead to address weak points in the relationship of people and livestock, and possible action to address expensive, regionally and globally significant infectious disease issues. China has taken the matter seriously, closing public access to some major nature reserves on bird migratory routes (e.g., at Qinghai Lake).

Safety, Quality and Competitiveness of Food Supply Chains

If China is to maximize the potential benefits from its food chain (domestic and export markets), it will have to generate crops, animals and foods that are of equal safety/quality to comparable goods offered in trade by its competitors. Specifically, it will have to:

- Reduce residues in animal products. Fifty per cent of China’s food chain exports are aquaculture products. The limiting factor causing problems in first tier markets (U.S., Japan, EU) is chemical residues.

- Create a “Disease Free Zone (DFZ)” for foot and mouth Disease and hog cholera and use it to ship pork to first-tier markets (U.S., Japan, EU). The current idea is to use HainanIsland as a DFZ to get exports up and running from this island to create credibility in the international market, before trying to export to the first-tier markets from DFZs that China is trying to create in Sichuan, Shandong and Jilin. These latter DFZs have little credibility for international trade as they have porous borders that allow disease to spread. No meat can be exported to first-tier markets while China has diseases like those listed above. Pork is probably the next animal product that China should try to export as it has half the world’s hogs and can produce at lower costs than developed country competitors.

- Improve quality in its crops (e.g., meet Japanese specifications for vegetable quality); animals (e.g., produce lean pork for Malaysia—a predominantly Muslim country with a 30 per cent Chinese minority who want pork); and food (e.g., introduce a grading system like the U.S. and Canada for all animal species, thus providing graded pork, beef, etc.).

- Safety and quality are important deterrents to China maximizing its opportunities in these post-WTO accession times. China is now the world’s third largest importer of food and agriculture products and the fifth largest exporter. It is on track to becoming the third largest importer and exporter in a few years. While it only imports and exports a small proportion of national production, national production is so large that this small proportion is still a large quantity. China now sends some aquaculture products and vegetables to first-tier markets (with ongoing residue and other quality problems!). However, less well known are its exports to second tier markets along its borders (e.g., Mongolia and Russia), which are less demanding regarding safety and quality, but who pay second-tier prices.

- Adherence to international standards will be important for exports of food products, but also for protecting the domestic market against import competition. As the affluence of urban Chinese consumers grows, so will their demand for safety and quality assurance of food products. If this assurance comes with imported food rather than from domestic supplies, food imports will grow at the expense of domestic producers.

- The 11th Five-Year Plan commitment in this regard is stated as: “We will pool our resources to launch special campaigns to promote food safety, strictly control market access for food products, and strengthen oversight and management of the entire production and distribution process to assure the people of the safety of the food supply.”

Alien Invasive Species

China may be the recipient of invasive species (Alien species) problems or be a contributor to their occurrence elsewhere. While the number of documented invasions coming out of China and adversely affecting other countries remains rather small, the reverse list is growing every day. The problems faced by invasive species in China are potentially enormous and increasing. A special Web site remains dedicated to this subject as a legacy of the work of the CCICED Biodiversity Task Force,[48] which lists details and maps for 123 of the most serious invasive alien species in China. A book on invasive species has been published based on this work and several international workshops have subsequently taken a deep interest in this topic.

Invasive alien species are most aggressive in colonizing degraded and dynamic ecosystems of which China is one great example. China is particularly susceptible to invasion because its range of [[habitat]s] and conditions are so great that any species gaining entry into the country will probably find a suitable living habitat. The fast pace with which China is being exposed to new potential invasive species is a result of China’s phenomenal growth in world trade. China is now importing raw materials from all corners of the world and many containers remain sealed until they reach destinations deep within China’s territories.

A continuing lack of awareness or interest in the threat leads to complacency by local government agencies. Even botanical gardens that should know better continue to bring into China as many new species as they can out of scientific curiosity and competitive pride, but without concern as to the risks involved in such introductions.

New agricultural or forestry pests, and new fish and other aquatic species get noticed because they affect economic sectors directly but species able to invade open spaces, forest ecosystems and other wild lands pass completely unnoticed.

China is poorly equipped to tackle such problems having few taxonomists to recognize or deal with invasive species. Newly recruited and poorly trained guards stationed in the very extensive Protected Areas system are unable to spot or react to the arrival of new species. There is a need to put in place appropriate and sound sanitary and phytosanitary measures for import control at China’s borders.

Existence Value of Protected Areas and Species in China

The numbers of international visitors to China grow at a spectacular pace. The publicity of the 2008 Beijing Olympics will carry over for years after the games, drawing visitors to China. China also increasingly markets its biological diversity and unique natural areas as reasons to become a tourist in remote areas of the country. But the lure of visiting China’s natural areas and growing system of protected areas is a large part of China’s attraction and the rare and famous species for which China is justly renowned all add their weight to the equation—giant panda, red panda, takin, golden monkeys, elusive tigers, alligators, dolphins and rare pheasants all have their devotees. Specialists set off in search of equally spectacular butterflies, birds, rhododendrons and other ornamental plants.

These are economic magnets that can theoretically serve China for many decades with value growing as the world offers ever fewer safe wild places to explore. But despite a huge increase in the area and number of protected areas for wildlife, and now more than 5,000 scenic sites that cover about 15 per cent of the land surface of the country, management standards and law enforcement remain so weak that wild [[population]s] continue to dwindle and the lure of the wild may not endure unless a renewed effort is placed on saving them.

Climate Change, Human Activity and Biodiversity

There can be little doubt that China and other countries with vast land and water areas will face many ecological impacts of climate change. These impacts will be costly to address, whether through adaptation or mitigation. China on its own cannot prevent change, nor has it been the major contributor to greenhouse gases that have accumulated since the industrial revolution. It is the impact of the rest of the world plus China that counts. However, climate change will not act in isolation. Local activities and various national development and other policies will be important, affecting ecological services and biological diversity. An example of how these factors might interact is shown in Box 4 concerning the Qinghai Plateau.

The worldwide concern for China’s biodiversity and ecologically sensitive areas is part of the rationale for the Global Environment Facility (GEF)’s substantial investments for protection of China’s biodiversity. Also, for programs in China funded by aid organizations of the EU, and by countries such as Norway. International concern for nature conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity has drawn other organizations into China, including WWF, The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and Conservation International.

Conclusions about Biosecurity and Biodiversity Conservation Although China is investing considerable effort in dealing with these topics, it is difficult to be highly optimistic about outcomes over the short run. China’s situation is of interest to the world for reasons of both public health and conservation. The two interests are intersecting to a greater extent than ever before, but they are also coming up against entrenched economic interests as well as the problems of dealing with rural poverty. While it is possible to take steps such as setting areas off limit, carrying out culls and prohibiting the sale of wildlife for food or for other uses, it is quite another matter to create an effective enforcement approach. A large part of China’s problems with biodiversity (One Lifeboat: Chapter 3) protection can be linked to trade. It has been difficult to make CITES work well, and the rapid rise in imports and exports has created problems of invasive species (Alien species). In the future, domestic and international tourism to China may create additional problems (although also certain opportunities) for biodiversity protection.

The international conservation community, and now the international public health authorities, play an important role in international perceptions about China concerning its efforts for conservation and disease control. There is a need to backstop these external communications efforts with additional research and cooperative work with Chinese experts. Almost certainly major efforts will be needed to understand more clearly the impacts of climate change on biodiversity, plant, animal and human disease vectors, and other difficult topics about which there is limited knowledge today.

Case Study 4 – Regional Environmental Impacts – River and Marine Water Issues

In November 2006, the Songhua River in northern China was contaminated by a serious spill of benzene, aniline and nitrobenzene from the Jilin Petrochemical Corporation, in Jilin Province. The contamination plume flowed past the city of Harbin, and eventually affected the large Heilongjiang River, a natural boundary with Russia (the Amur River within Russia), eventually discharging into Russian coastal waters of the Sea of Okhotsk.[49] This event led to a temporary shutdown of the drinking water supply for several million people, and raised public and diplomatic concerns on both sides of the Sino-Russian border.