Bolivia

Bolivia Is a landlocked nation of ten million people in South America, southwest of Brazil and bordering Countries and Regions of the World Collection  Argentina and Paraguay in the south, and Chile and Peru in the west.

Argentina and Paraguay in the south, and Chile and Peru in the west.

Bolivia shares control of Lake Titicaca, world's highest navigable lake (elevation 3,805 metres), with [[Peru].]

It is is one of two land-locked countries in South America; the other being Paraguay.

Its major environmental issues include:

- the clearing of land for agricultural purposes and the international demand for tropical timber are contributing to deforestation (Deforestation in Amazonia);

- soil erosion from overgrazing and poor cultivation methods (including slash-and-burn agriculture);

- desertification;

- loss of biodiversity; and,

- industrial pollution of water supplies used for drinking and irrigation.

Bolivia, named after independence fighter Simon Bolivar, broke away from Spanish rule in 1825.

Much of its subsequent history has consisted of a series of nearly 200 coups and countercoups.

Democratic civilian rule was established in 1982, but leaders have faced difficult problems of deep-seated poverty, social unrest, and illegal drug production.

In December 2005, Bolivians elected Movement Toward Socialism leader Evo Morales president - by the widest margin of any leader since the restoration of civilian rule in 1982 - after he ran on a promise to change the country's traditional political class and empower the nation's poor, indigenous majority. However, since taking office, his controversial strategies have exacerbated racial and economic tensions between the Amerindian populations of the Andean west and the non-indigenous communities of the eastern lowlands.

In December 2009, President Morales easily won reelection, and his party took control of the legislative branch of the government, which will allow him to continue his process of change. In October 2011, the country held its first judicial elections to appoint judges to the four highest courts.

Contents

Geography

Location: Central South America, southwest of Brazil

Geographic Coordinates: 17 00 S, 65 00 W

Area: 1,098,580 km2 (1,084,390 km2 land and 14,190 km2 water)

arable land: 2.78%

permanent crops: 0.19%

other: 97.03% (2005)

Land Boundaries: 6,940 km - border countries: Argentina 832 km, Brazil 3,423 km, Chile 860 km, Paraguay 750 km, Peru 1,075 km

Chile and Peru rebuff Bolivia's reactivated claim to restore the Atacama corridor, ceded to Chile in 1884, but Chile offers instead unrestricted but not sovereign maritime access through Chile for Bolivian natural gas.

Coastline: None

Maritime Claims: None

Natural Hazards: Flooding in the northeast (March-April)

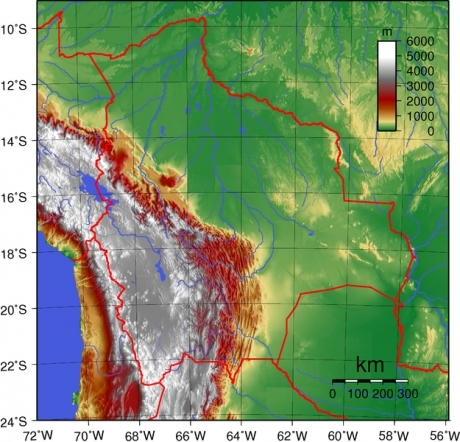

Terrain: Rugged Andes Mountains with a highland plateau (Altiplano), hills, lowland plains of the Amazon Basin. The lowest point is Rio Paraguay (90 metres) and the highest point is Nevado Sajama (6,542 metres).

Climate: Varies with altitude; humid and tropical to cold and semiarid.

|

Topography of Bolivia. Source: Wikimedia Commons. |

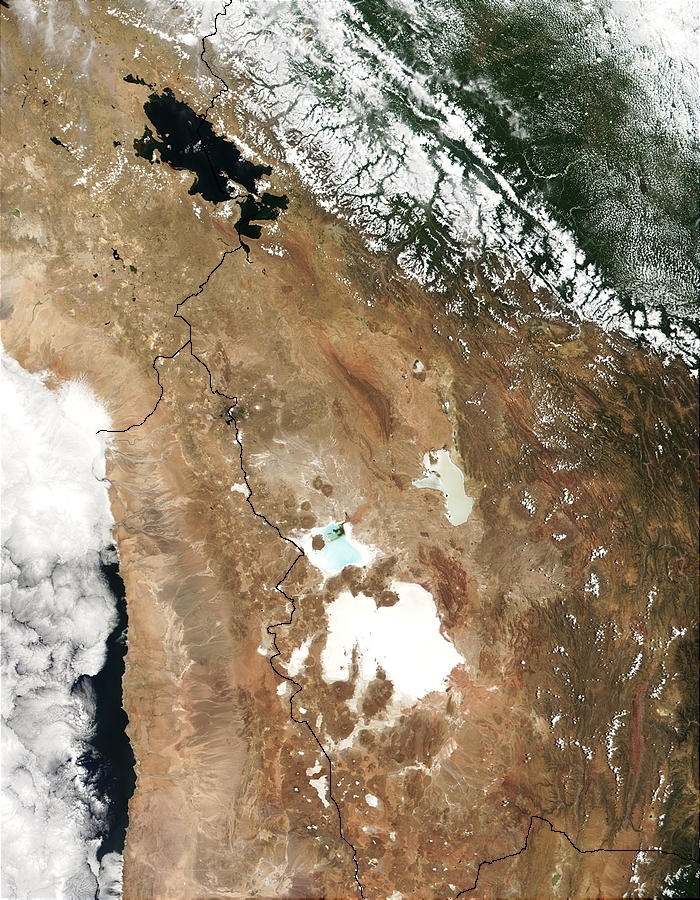

Source: NASA. Credit: Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC |

Normally obscured by clouds, Bolivia is amazingly clear in the true-color MODIS image (above right) acquired June 20, 2002. Bounded by Brazil to the north and west, Paraguay and Argentina to the south, and Peru and Chile to the east, Bolivia is completely landlocked. A good portion of Bolivia is dominated by the Andes, but it also lays claim to lush forests and pasture lands in the Amazon Basin.Bolivia's agricultural crops include soybeans, coffee, coca, cotton, corn, sugarcane, rice, potatoes, and timber. A number of agricultural plots are visible in central Bolivia. Some large plots are arranged in a circular star shape, with water sources at the center and the agricultural plots radiating outwards. Adjacent to them (down and to the right) are more traditional shaped plots (more rectangular).One of Bolivia's main exports is tropical timber. Visible in this image are areas where the timber has been harvested. The deforestation patterns tend to follow major roads first, then smaller roads adjoining main roads. These patterns resemble the growth of ice crystals and are best viewed in the higher resolutions of this image. Deforestation is visible along the green edge of the Andes in central Bolivia.

Biodiversity and Ecology

See also: |

Source: World Wildlife Fund |

High in the Andes Mountains of South America, Lake Titicaca straddles Peru (upper left) and Bolivia. This MODIS true-color image from November 4, 2001, highlights the diverse landforms of the region. In the La Paz region of Bolivia, the Andes are still snow-covered ; some of the peaks hold snow year round. Chile (at left along the coast of the Pacific Ocean) presents a barren-looking landscape, but some green is evident in the high-resolution image, especially around rivers. The large white areas are large salt flats and seasonal salt lakes.

Lake Titicaca is an important research site for studies of previous climate episodes during Earth's history. The highest of Earth's large lakes, it sits at an altitude of 12,500 ft. on the Altiplano, a high plateau, and the lake bed is deep with sediment layers that can tell a story about climate that reaches back hundreds of thousands-possibility even millions -- of years. Source: NASA. Credit: Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

People and Society

Population: 10,290,003 (July 2012 est.)

According to the 2001 census, Bolivia’s ethnic distribution is estimated to be 62% indigenous and 38% non-indigenous (all categories are self-identified). The largest of the approximately three dozen indigenous groups are the Quechua (31% or 1.6 million), Aymara (25% or 1.3 million), Chiquitano (2% or 112,000), and Guarani (2% or 112,000). No other indigenous groups represent more than 0.5% of the population. German, Croatian, Serbian, Asian, Middle Eastern, Canadian and other minorities also live in Bolivia. Many of these minorities descend from families that have lived in Bolivia for several generations.

Bolivia is one of the least developed countries in South America. Almost two-thirds of its people, many of whom are subsistence farmers, live in poverty. Population density ranges from less than one person per square kilometer in the southeastern plains to about 10 per square kilometer (25 per sq. mi.) in the central highlands. The annual population growth rate is about 1.69% (2010).

The great majority of Bolivians are Roman Catholic, although Protestant denominations are expanding rapidly. Many indigenous communities interweave pre-Columbian and Christian symbols in their religious practices.

According to the 2001 census, the literacy rate was 75%, with 14% responding as illiterate. The literacy rate is low in many rural areas. Under President Morales, a number of areas have been declared “illiteracy free” but the level of literacy is often quite basic, restricted to writing one’s name and recognizing numbers. Approximately 20% of the population has received no formal education.

The socio-political development of Bolivia can be divided into three distinct periods: pre-Columbian, colonial, and republican. Important archaeological ruins, gold and silver ornaments, stone monuments, ceramics, and weavings remain from several important pre-Columbian cultures. Major ruins include Tiwanaku, Samaipata, Incallajta, and Iskanwaya. The country abounds in other sites that are difficult to reach and have seen little archaeological exploration.

The Spanish brought a tradition of religious art which, in the hands of local indigenous and mestizo builders and artisans, developed into a rich and distinctive style of architecture, painting, and sculpture known as “Mestizo Baroque.” The colonial period produced the paintings of Perez de Holguin, Flores, Bitti, and others as well as the skilled work of unknown stonecutters, woodcarvers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths. An important body of native baroque religious music from the colonial period was recovered and has been performed internationally to wide acclaim since 1994.

Important 20th-century Bolivian artists include, among others, Guzman de Rojas, Arturo Borda, Maria Luisa Pacheco, and Marina Nunez del Prado. Bolivia has rich folklore. Its regional folk music is distinctive and varied. The “devil dances” at the annual Oruro carnival are among the great South American folkloric events, as are the lesser-known carnival at Tarabuco and the “Gran Poder” festival in La Paz.

Ethnic groups: Quechua 30%, mestizo (mixed white and Amerindian ancestry) 30%, Aymara 25%, white 15%

Age Structure: Median age: 21.9 years

0-14 years: 34.6% (male 1,785,453/female 1,719,173)

15-64 years: 60.7% (male 3,014,419/female 3,129,942)

65 years and over: 4.6% (male 207,792/female 261,904) (2011 est.)

Population Growth Rate: 1.664% (2012 est.)

| Lake Titicaca from Bolivian side. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Dalí desert in Potosí Department, Bolivia. Source: DeFries/Flikr |

| The Altiplano, an area of high plateau in the Andes, is visible in the foreground with the peaks of the Cordillera Real in the background. Source: Karan Gulaya/Wikimedia Commons |

Birthrate: 24.24 births/1,000 population (2012 est.)

Death Rate: 6.76 deaths/1,000 population (July 2012 est.)

Net Migration Rate: -0.84 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2012 est.)

Life Expectancy at Birth: 67.9 years

male: 65.16 years

female: 70.77 years (2012 est.)

Total Fertility Rate: 2.93 children born/woman (2012 est.)

Languages: Spanish 60.7% (official), Quechua 21.2% (official), Aymara 14.6% (official), foreign languages 2.4%, other 1.2% (2001 census)

Literacy: 86.7% (2001 census)

Urbanization: 67% of total population (2010) growing at an annual rate of change of 2.2% (2010-15 est.)

History

The Andean region has probably been inhabited for some 20,000 years. Around 2000 B.C., the Tiwanakan culture developed at the southern end of Lake Titicaca. The Tiwanakan culture centered around and was named after the great city Tiwanaku. The people developed advanced architectural and agricultural techniques before disappearing about 1200 A.D., probably because of extended drought. Roughly contemporaneous with the Tiwanakan culture, the Moxos in the eastern lowlands and the Mollos north of present-day La Paz also developed advanced agricultural societies that had dissipated by the 13th century. Around 1450, the Quechua-speaking Incas entered the area of modern highland Bolivia and added it to their empire. They controlled the area until the Spanish conquest in 1525.

During most of the Spanish colonial period, this territory was called “Upper Peru” or “Charcas” and was under the authority of the Viceroy of Lima. Local government came from the Audiencia de Charcas located in Chuquisaca (La Plata--modern-day Sucre). Bolivian silver mines produced much of the Spanish empire’s wealth. Potosi, site of the famed Cerro Rico--“Rich Mountain”--was, for many years, the largest city in the Western Hemisphere. As Spanish royal authority weakened during the Napoleonic wars, sentiment against colonial rule grew. Independence was proclaimed in 1809. Sixteen years of struggle followed before the establishment of the republic, named after Simon Bolivar, on August 6, 1825.

Independence did not bring stability. For nearly 60 years, short-lived, weak institutions and frequent coups characterized Bolivian politics. The War of the Pacific (1879-83) demonstrated Bolivia’s weakness when it was defeated by Chile. Chile took lands that contained rich nitrate fields and removed Bolivia’s access to the sea.

An increase in world silver prices brought Bolivia prosperity and political stability in the late 1800s. Tin eventually replaced silver as the country’s most important source of wealth during the early part of the 20th century. Successive governments controlled by economic and social elites followed laissez-faire capitalist policies through the first third of the century.

Indigenous living conditions remained deplorable. Forced to work under primitive conditions in the mines and in nearly feudal status on large estates, indigenous people were denied access to education, economic opportunity, or political participation. Bolivia’s defeat by Paraguay in the Chaco War (1932-35) marked a turning point. Great loss of life and territory discredited the traditional ruling classes, while service in the army produced stirrings of political awareness among the indigenous people and more of a shared national identity. From the end of the Chaco War until the 1952 revolution, the emergence of contending ideologies and the demands of new groups convulsed Bolivian politics.

Revolution and Turmoil

Bolivia’s first modern and broad-based political party was the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR). Denied victory in the 1951 presidential elections, the MNR led a successful revolution in 1952. Under President Victor Paz Estenssoro, the MNR introduced universal adult suffrage, carried out a sweeping land reform, promoted rural education, and nationalized the country’s largest tin mines.

Twelve years of tumultuous rule left the MNR divided. In 1964, a military junta overthrew President Paz Estenssoro at the outset of his third term. The 1969 death of President Rene Barrientos, a former junta member elected president in 1966, led to a succession of weak governments. The military, the MNR, and others installed Col. (later General) Hugo Banzer Suarez as president in 1971. Banzer ruled with MNR support from 1971 to 1974. Then, impatient with schisms in the coalition, he replaced civilians with members of the armed forces and suspended political activities.

The economy grew impressively during most of Banzer’s presidency, but human rights violations and fiscal crises undercut his support. He was forced to call elections in 1978, and Bolivia again entered a period of political turmoil. Elections in 1978, 1979, and 1980 were inconclusive and marked by fraud. There were coups, counter-coups, and caretaker governments.

In 1980, Gen. Luis Garcia Meza carried out a ruthless and violent coup. His government was notorious for human rights abuses, narcotics trafficking, and economic mismanagement. Later convicted in absentia for crimes, including murder, Garcia Meza was extradited from Brazil and began serving a 30-year sentence in 1995 in a La Paz prison.

After a military coup forced Garcia Meza out of power in 1981, three separate military governments in 14 months struggled unsuccessfully to address Bolivia’s growing problems. Unrest forced the military to convoke the Congress elected in 1980 and allow it to choose a new chief executive. In October 1982--22 years after the end of his first term of office (1956-60)--Hernan Siles Zuazo again became president. Severe social tension, exacerbated by hyperinflation and weak leadership, forced him to call early elections and relinquish power a year before the end of his constitutional term.

Return to Democracy

In the 1985 elections, Gen. Banzer’s Nationalist Democratic Action Party (ADN) won a plurality of the popular vote (33%), followed by former President Paz Estenssoro’s MNR (30%) and former Vice President Jaime Paz Zamora’s Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR, at 10%). With no majority, the Congress had constitutional authority to determine who would be president. In the congressional run-off, the MIR sided with MNR, and Paz Estenssoro was selected to serve a fourth term as president. When he took office in 1985, he faced a staggering economic crisis. Economic output and exports had been declining for several years. Hyperinflation meant prices grew at an annual rate of 24,000%. Social unrest, chronic strikes, and drug trafficking were widespread.

In 4 years, Paz Estenssoro’s administration achieved a measure of economic and social stability. The military stayed out of politics; all major political parties publicly and institutionally committed themselves to democracy. Human rights violations, which tainted some governments earlier in the decade, decreased significantly. However, Paz Estenssoro’s accomplishments came with sacrifice. Tin prices collapsed in October 1985. The collapse came as the government moved to reassert control of the mismanaged state mining enterprise and forced the government to lay off over 20,000 miners. Although this economic “shock treatment” was highly successful from a financial point of view and tamed devastatingly high rates of hyperinflation, the resulting social dislocation caused significant unrest.

MNR candidate Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada finished first in the 1989 elections (23%), but no candidate received a majority of popular votes. Again, Congress would determine the president. The Patriotic Accord (AP) between Gen. Banzer’s ADN and Jaime Paz Zamora’s MIR, the second- and third-place finishers (at 22.7% and 19.6%, respectively), led to Paz Zamora’s assuming the presidency.

Even though Paz Zamora had been a Marxist in his youth, he governed as a moderate, center-left president, and marked his time in office with political pragmatism. He continued the economic reforms begun by Paz Estenssoro. Paz Zamora also took a fairly hard line against domestic terrorism, authorizing a 1990 attack on terrorists of the Nestor Paz Zamora Committee and the 1992 crackdown on the Tupac Katari Guerrilla Army (EGTK).

The 1993 elections continued the growing tradition of open, honest elections and peaceful democratic transitions of power. The MNR defeated the ruling coalition, and Gonzalo “Goni” Sanchez de Lozada was named president by a coalition in Congress.

Sanchez de Lozada pursued an aggressive economic and social reform agenda, relying heavily on successful entrepreneurs-turned-politicians like him. The most dramatic program--“capitalization,” a form of privatization under which investors acquired 50% ownership and management control of the state oil corporation, telecommunications system, airlines, railroads, and electric utilities--was used to generate funds for a new pension and healthcare system called BonoSol. BonoSol funding was popular in the country but the concept of capitalization was strongly opposed by certain segments of society, with frequent and sometimes violent protests from 1994 through 1996. During his term, Sanchez de Lozada also created the "Popular Participation Law," which devolved much of the central government's authority to newly-created municipalities, and the INRA law, which significantly furthered land redistribution efforts begun under the MNR after the 1952 revolution.

In the 1997 elections, Gen. Hugo Banzer, leader of the ADN, returned to power democratically after defeating the MNR candidate. The Banzer government continued the free market and privatization policies of its predecessor. The relatively robust economic growth of the mid-1990s continued until regional, global, and domestic factors contributed to a decline in economic growth. Job creation remained limited throughout this period, and public perception of corruption was high. Both factors contributed to an increase in social protests during the second half of Banzer’s term.

Rising international demand for cocaine in the 1980s and 1990s led to a boom in coca production and to significant peasant migration to the Chapare region. To reverse this, Banzer instructed special police units to physically eradicate the illegal coca in the Chapare. The policy produced a sudden and dramatic 4-year decline in Bolivia’s illegal coca crop, to the point that Bolivia became a relatively small supplier of coca for cocaine. In 2001, Banzer resigned from office after being diagnosed with cancer. He died less than a year later. Banzer’s U.S.-educated vice president, Jorge Quiroga, completed the final year of the term.

In the 2002 national elections, former President Sanchez de Lozada (MNR) again placed first with 22.5% of the vote, followed by coca union leader Evo Morales (Movement Toward Socialism, MAS) with 20.9%. The MNR platform featured three overarching objectives: economic reactivation (and job creation), anti-corruption, and social inclusion.

A 4-year economic recession, difficult fiscal situation, and longstanding tensions between the military and police led to the February 12-13, 2003, violence that left more than 30 people dead and nearly toppled Sanchez de Lozada’s government. The government stayed in power, but was unpopular.

Trouble began again in the so-called “Gas Wars” of September/October 2003, which sparked over a proposed project to export liquefied natural gas, most likely through Chile. A hunger strike by Aymara leader and congressional deputy Felipe “Mallku” Quispe led his followers to begin blocking roads near Lake Titicaca. About 800 tourists, including some foreigners, were trapped in the town of Sorata. After days of unsuccessful negotiations, Bolivian security forces launched a rescue operation, but on the way out, were ambushed by armed peasants and a number of people were killed on both sides. The incident ignited passions throughout the highlands and united a loose coalition of protestors to pressure the government. Anti-Chile sentiment and memories of three major cycles of non-renewable commodity exports (silver through the 19th century, guano and rubber late in the 19th century, and tin in the 20th century) touched a nerve with many citizens. Tensions grew and La Paz was subjected to protesters’ blockades. Violent confrontations ensued, and approximately 60 people died when security forces tried to bring supplies into the besieged city.

On October 17, large demonstrations under the leadership of Evo Morales forced Sanchez de Lozada to resign. Vice President Carlos Mesa Gisbert assumed office and restored order. Mesa appointed a non-political cabinet and promised to revise the constitution through a constituent assembly, revise the hydrocarbons law, and hold a binding referendum on whether to develop the country’s natural gas deposits, including for export. The referendum took place on July 18, 2004, and Bolivians voted overwhelmingly in favor of development of the nation’s hydrocarbons resources. But the referendum did not end social unrest. In May 2005, large-scale protests led to the congressional approval of a law establishing a 32% direct tax on hydrocarbons production, which the government used to fund new social programs. After a brief pause, demonstrations resumed, particularly in La Paz and El Alto. President Mesa offered his resignation on June 6, and Eduardo Rodriguez, the president of the Supreme Court, assumed office in a constitutional transfer of power. Rodriguez announced that he was a transitional president, and called for elections within 6 months.

Evo Morales Elected

On December 18, 2005, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) candidate Juan Evo Morales Ayma was elected to the presidency by 54% of the voters. Bolivia’s first president to represent the indigenous majority, Morales continued to serve as leader of the country’s coca unions. During his campaign, Morales vowed to nationalize hydrocarbons and to empower the indigenous population. Morales was highly critical of what he termed “neo-liberal” economic policies. On January 22, 2006, Morales and Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera were inaugurated.

On May 1, 2006, the government issued a decree nationalizing the hydrocarbons sector and calling for the renegotiation of contracts with hydrocarbons companies. Morales promoted greater state control of natural resource industries, particularly hydrocarbons and mining, and of the telecommunications sector (see Economy section). These policies pleased Morales’ supporters but complicated Bolivia’s relations with some of its neighboring countries, foreign investors, and members of the international community.

Fulfilling another campaign promise, Morales convoked a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. The assembly convened on August 6, 2006, and planned to complete its work by August 2007; however, the Congress extended its mandate to December 2007 after the assembly faced political deadlock over its voting rules. The MAS approved a constitution without the opposition vote in November 2007, in a controversial assembly session in which opposition delegates were blocked from voting by demonstrators and the armed forces. On December 14, 2007, Morales presented the constitutional text to the National Congress to request a referendum for its approval in 2008. The opposition-controlled Senate prevented the referendum legislation from moving forward.

Political tensions between the government and the opposition over the new constitution, autonomy statutes passed by some departmental legislatures, and disputes over the division of tax proceeds from the hydrocarbon industry led to civil unrest, which culminated in violent discord in August and September 2008 in eastern departments.

On October 21, 2008, with a crowd of at least 50,000 pro-government supporters surrounding the National Congress, the government and congressional opposition agreed on final draft text for the new constitution. Voters approved the new constitution on January 25, 2009, and it entered into force on February 7, 2009. The new constitution called for national elections to be held in December.

Current Administration

President Morales was re-elected on December 6, 2009, with 64% of the vote, followed by former Cochabamba Prefect Manfred Reyes Villa (27%) and business leader Samuel Doria Medina (6%). The ruling MAS party won 88 out of 130 deputy races and 26 out of 36 Senate seats, gaining a two-thirds majority of the Plurinational Assembly.

After re-election, President Morales prioritized implementation of the new constitution. Morales and Vice President Garcia Linera pledged to move the country toward "communitarian socialism," with an "integrated" economic system featuring a strong state presence. The Morales administration promised greater investment in infrastructure, education, health, and a "great leap forward" in industrialization (including development of lithium reserves and the country's first satellite).

The 2009 constitution included mandates for implementing legislation, including five major pieces of legislation by July 2010. Required legislation included bills to codify and coordinate interactions between the co-equal "ordinary" and indigenous justice systems; reform and restructure the country's Supreme Court, Constitutional Tribunal, and National Electoral Court (considered the fourth branch of government); and define the roles and responsibilities of the central government and four autonomy levels: departmental, regional, municipal, and indigenous.

On December 26, 2010, the Morales administration removed subsidies for gasoline overnight. Gas prices rose 73% and, following nationwide protests over the “gasolinazo,” Morales reintroduced the subsidies. Morales’ popularity also was affected by police intervention in a march by lowland indigenous persons on September 25, 2011 protesting the development of a road through their protected territory. On October 16, 2011, the government held popular elections for the four highest judicial courts in the country. A majority of votes were returned null or blank due to frustrations over campaign restrictions, the recent police intervention, and complicated ballots.

President Morales held a national summit in late 2011 and early 2012 to formulate a new set of laws to address foreign investment, the hydrocarbon industry, and other issues. On January 23, 2012 Morales announced a round of cabinet changes, removing seven ministers and replacing two others in his 20-person cabinet.

Government

A new constitution was promulgated February 7, 2009, replacing Bolivia’s 1967 constitution. The 2009 constitution provides for legislative, executive, judicial, and electoral branches of government.

The National Congress, renamed Plurinational Assembly, is composed of two bodies: the Chamber of Deputies and the Chamber of Senators. The Chamber of Deputies has 130 members, with 70 members selected by direct vote, 53 by party list, and seven in special indigenous areas. The Chamber of Senators has 36 members, with 4 from each of the 9 departments. The executive consists of the president, vice president, and the ministers of state. The president and vice president are selected through national elections. The ministers of state are appointed.

The 2009 constitution strengthened the executive branch and centralized political and economic decision-making. It also provided new powers and responsibilities at the departmental, municipal, and regional areas, as well as in newly-created indigenous autonomous areas.

|

Government Type: Republic; note - the new constitution defines Bolivia as a "Social Unitarian State" Capital: La Paz - 1.642 million (2009) Other Major Cities: Santa Cruz 1.584 million; Sucre 281,000 (2009) Administrative divisions: 9 departments (departamentos, singular - departamento);

Independence Date: 6 August 1825 (from Spain) Legal System: civil law system with influences from Roman, Spanish, canon (religious), French, and indigenous law. Bolivia has not submitted an International Court of Justice (ICJ) jurisdiction declaration; but accepts International criminal court (ICCt) jurisdiction. |

Source: Wikimedia Commons |

The judiciary consists of a Supreme Court, an independent Constitutional Tribunal, a Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and departmental and lower courts. The 2009 constitution reformed the procedure for selecting judicial officials for the Supreme Court, Constitutional Tribunal, and Supreme Electoral Tribunal to make these officials subject to election by national vote, which occurred on October 16, 2011. To stand for election, candidates first must be approved by a two-thirds majority vote of all Plurinational Assembly members present. Judges are elected to 6-year terms.

International Environmental Agreements

Bolivia is party to international agreements on Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, and Wetlands.

Economy

Bolivia is one of the poorest and least developed countries in Latin America.

Following a disastrous economic crisis during the early 1980s, reforms spurred private investment, stimulated economic growth, and cut poverty rates in the 1990s.

The period 2003-05 was characterized by political instability, racial tensions, and violent protests against plans - subsequently abandoned - to export Bolivia's newly discovered natural gas reserves to large northern hemisphere markets.

In 2005, the government passed a controversial hydrocarbons law that imposed significantly higher royalties and required foreign firms then operating under risk-sharing contracts to surrender all production to the state energy company in exchange for a predetermined service fee.

The global recession slowed growth, but Bolivia recorded the highest growth rate in South America during 2009.

During 2010-11 increases in world commodity prices resulted in large trade surpluses.

However, a lack of foreign investment in the key sectors of mining and hydrocarbons and higher food prices pose challenges for the Bolivian economy.

Bolivia’s estimated 2011 gross domestic product (GDP) totaled $23.3 billion. Economic growth was estimated at about 5.1%, and inflation was estimated at about 6.9%.

The increase in GDP primarily reflected contributions from oil and gas production (7.9%); electricity, water, and gas distribution (7.6%); construction (7.2%); transport and communications (6.0%); and financial services (5.5%). However, some sectors lost momentum during 2011; this was especially notable in oil and gas production (from a 15.1% growth rate in the first quarter of 2011 to 7.5% in the fourth quarter of 2011), and electricity, water, and gas distribution (from 8.9% to 7.7%). Only manufacturing and mining continued to improve in performance numbers throughout the year.

The Bolivian Government has signaled its intent to nationalize all companies that were previously privatized in the 1990s under the process of capitalization. In this process, state-owned companies were privatized up to a 50% interest (the state controlled the other 50% interest). The government has nationalized all hydrocarbons transport and sales (private and foreign state-owned firms remain in production and services), part of the electricity industry, the biggest telecommunications company, a tin smelting plant, and a cement plant. To take control of these companies the government forced private entities to sell shares to the government, but often at below-market prices. Some of the affected companies have cases pending with international arbitration bodies.

The future of new nationalizations is not clear, as there are still some capitalized companies that are under private control, including the railroad, airport services, and electricity transport and distribution companies. There have been no nationalizations of companies that were, from the start, privately owned. The nationalization process has not discriminated by country; some of the countries affected were the United States, France, the U.K., Spain, Argentina, and Chile, among others.

Exports rose by more than 30% between 2010 and 2011 to $9.1 billion, due mostly to increased commodity prices, not increased volume. In 2011, Bolivia’s top export products were: hydrocarbons (45% of total exports), minerals (27%), manufactured goods (24%), and agricultural products (4%). Bolivia’s trade with neighboring countries is growing, in part because of several regional preferential trade agreements. Bolivia’s top trading partners in 2011 in terms of exports were Brazil (33%), Argentina (11%), United States (10%), Japan (6%), Peru (5%), South Korea (5%), Belgium (4%), China (3%), and Venezuela (3%).

Bolivian tariffs are low; however, manufacturers complain that the tax-rebate program that allows some companies to claim refunds of import taxes on capital equipment is inefficient, with many companies now owed millions of dollars by the Bolivian Government, which can take years to recover.

From 2010 to 2011, Bolivian imports rose by 41% to a total of $7.6 billion. Bolivia imports many industrial supplies and inputs such as replacement parts, chemicals, software, and other production items (31% of total imports), capital goods (21%), fuel (13%), and consumer goods (10%). Top import products within these categories were machinery and mechanical appliances (17% of total imports), chemical products (14%), fuels and oils (14%), vehicles (13%), minerals (8%), and food (7%). Bolivia also imports significant quantities of steel, electrical machinery equipment and parts, and plastics and plastic products.

While Bolivia's trade with the United States increased in 2011, the U.S. remains Bolivia's third-largest trading partner behind Brazil and Argentina, due to the large exports of Bolivian gas to those two countries. The U.S. supplied 11% of Bolivia's imports and received 10% of its exports. Bolivia has a total trade surplus of $1.5 billion, of which the U.S. accounts for $44 million. Bolivia’s major exports to the United States are tin, silver and silver concentrates, petroleum products, Brazil nuts, quinoa, and jewelry. Its major imports from the United States are airplane parts, electronic equipment, chemicals, vehicles, wheat, and machinery.

GDP: (Purchasing Power Parity): $51.41 billion (2011 est.)

GDP-real growth rate: $23.9 billion (2011 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP): $4,800 (2011 est.)

GDP- composition by sector:

agriculture: 10%

industry: 40%

services: 50% (2011 est.)

Industries: Mining, smelting, petroleum, food and beverages, tobacco, handicrafts, clothing

Natural Resources: tin, natural gas, petroleum, zinc, tungsten, antimony, silver, iron, lead, gold, timber, hydropower

Currency: Bolivianos (BOB)

See: Energy profile of Bolivia

Foreign Relations

Bolivia traditionally has maintained normal diplomatic relations with all hemispheric states except Chile. Relations with Chile, strained since Bolivia’s defeat in the War of the Pacific (1879-83) and its loss of the coastal province of Atacama, were severed from 1962 to 1975 in a dispute over the use of the waters of the Lauca River. Relations were resumed in 1975, but broken again in 1978, over the inability of the two countries to reach an agreement that might have granted Bolivia sovereign access to the sea. Relations with Chile improved during the Michelle Bachelet administration. They are maintained today below the ambassadorial level.

In the 1960s, relations with Cuba were broken following Fidel Castro’s rise to power, but resumed under the Paz Estenssoro administration in 1985. Under President Morales, relations between Bolivia and Cuba have improved considerably, and Cuba has sent doctors and teachers to Bolivia. Relations with Venezuela are close, with Venezuela providing funding until recently for some social programs.

Bolivia is a member of the UN and some of its specialized agencies and related programs, the Organization of American States (OAS), Andean Community (CAN), Non-Aligned Movement, International Parliamentary Union, Latin American Integration Association (ALADI), World Trade Organization (WTO), Rio Treaty, Rio Group, Amazon Pact, Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States (CELAC), and an associate member of Mercosur. The UNASUR parliament will be located in Cochabamba, in the geographic center of Bolivia.

U.S.-BOLIVIAN RELATIONS

The United States and Bolivia have traditionally had cordial and cooperative relations. Development assistance from the United States to Bolivia dates from the 1940s; the U.S. remains a major partner for economic development, improved health, democracy, and the environment. In 1991, the U.S. Government forgave a $341 million debt owed by Bolivia to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) as well as 80% ($31 million) of the amount owed to the Department of Agriculture for food assistance. The United States has also been a strong supporter of forgiveness of Bolivia’s multilateral debt under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiatives.

USAID has been providing assistance to Bolivia since the 1960s and works with the Government of Bolivia, the private sector, and the Bolivian people to achieve equitable and sustainable development. In fiscal year 2012 USAID/Bolivia provided about $27 million in development assistance. USAID’s programs support Bolivia’s National Development Plan and are designed to address key issues, such as poverty and the social exclusion of historically disadvantaged populations, focusing efforts on Bolivia’s peri-urban and rural populations.

During the Morales administration bilateral relations deteriorated sharply, as the Bolivian Government escalated public attacks against the U.S. Government and began to dismantle key partnerships. In June 2008, the government endorsed the expulsion of USAID from Bolivia’s largest coca-growing region. In September 2008, President Morales accused Ambassador Philip S. Goldberg of conspiring against the government, declared him "persona non grata," and expelled him from Bolivia. In a reciprocal action, the Department of State expelled Bolivian Ambassador Gustavo Guzman later that month. In November 2008, President Morales expelled the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from the country, ending a 35-year history of engagement against narcotics production and trafficking.

Starting in May 2009, the U.S. and Bolivian governments engaged in a dialogue to improve relations, which culminated in the November 7, 2011 signing of a bilateral framework agreement normalizing relations. Both the U.S. and Bolivia have agreed to exchange Ambassadors in an important first step, and on February 28, 2012, U.S. and Bolivian delegates held high-level meetings in La Paz to discuss future relations. U.S. assistance programs to promote health and welfare, advance economic development, and fight narcotics production and trafficking remain active and effective in advancing common goals in Bolivia.

Bolivia’s international obligation to control illegal narcotics remains a major issue in the bilateral relationship. For centuries, a limited quantity of Bolivian coca leaf has been chewed and used in traditional rituals, but in the 1970s and 1980s the emergence of the drug trade led to a rapid expansion of coca cultivation used to make cocaine, particularly in the tropical Chapare region in the Department of Cochabamba (not a traditional coca-growing area). In 1988, a new law, Law 1008, recognized only 12,000 hectares in the Yungas as sufficient to meet the licit demand of coca. Law 1008 also explicitly stated that coca grown in the Chapare was not required to meet traditional demand for chewing or for tea, and the law called for the eradication, over time, of all “excess” coca.

Bolivia plans to expand legal coca production to 20,000 hectares and stresses development of legal commercial uses for coca leaf. The United States prefers long-term limits that track more closely with current estimated legal domestic demand of around 4,000 to 6,000 hectares. UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates place current cultivation at just over 30,000 hectares.

The United States has supported efforts to interdict the smuggling of coca leaves, cocaine, and precursor chemicals, as well as investigate and prosecute trafficking organizations. However, these efforts have been significantly constrained after the expulsion of DEA. The U.S. Government continues to finance alternative development programs and the counternarcotics police effort.