Yucatán dry forests

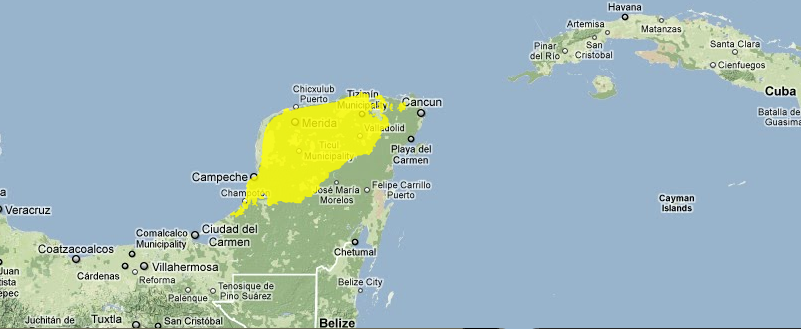

Located on the northwestern section of the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, the Yucatán dry forests ecoregion is generally topographically level with vegetation dominated by thorn scrub and cacti. Endemism is high due to the isolation of this dry forest; this region contains ten of the fourteen endemic cacti of the Yucatán Peninsula. This region is also important for migratory birds from the North America; twenty endemic birds are found in this ecoregion. This region is threatened by overgrazing and cattle ranching and agriculture development, at least one endemic species of cacti, Cola Lagarto (Pereskiopsis kellermanii) may have become extinct.

Contents

Location and general description

The region is situated on the northwestern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. The forests grow on a vast portion of flat terrain (less than 400 metres above sea level), composed of limestone of coraline origin.

Soils are generally young and of calcareous origin; and drainage is extensive, thus the soils hardly ever flood. The climate is tropical subhumid but becomes drier in the central portion of this region. As in other subtropical forests, there is a long dry season that is responsible for the deciduous nature of the forests. Precipitation levels do not reach above 1200 millimetres (mm)/year, although the northern portions of the ecoregion receive slightly less. Dominant vegetative species in the central portion of the region are: False Tamarind (Lysiloma latisiliquum) and Florida Fishpoison Tree (Piscidia piscipula), and may be associated withMexican Alvaradoa (Alvaradoa amorphoides), Gumbo Limbo (Bursera simaruba), Cigar-box Wood (Cedrela odorata), Fustic Tree (Chlorophora tinctoria),Yauco (Cordia gerascanthus) andChapulaltapa (Lonchocarpus rugosus) in other areas. The accompanying species are Walking Lady (Vitex gaumeri), Breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum), Warrie Wood (Caesalpinia gaumeri), Cigar-box Wood (Cedrela odorata), Kapok Tree (Ceiba pentandra) and False Mastic (Sideroxylon foetidissimum). In the northern part of the ecoregion, near the coast, cacti become more abundant. Common cactus species include: Royen's Tree Cactus (Pilosocereus royenii), Pterocereus gaumeri and Pitayo De Mayo (Stenocereus griseus). Herbaceous plants, epiphytes and fungi are rather scarce, but bromeliads like Tillandsia can be found growing on some trees.

Biodiversity

The dry forests of the Yucatán constitute a unique island of vegetation in the Gulf of Mexico region. They are isolated from other dry forests by the sea and by a vast extension of humid forests in the Maya region. Some researchers hypothesize that the isolation of the dry forests has been responsible for the unique composition of the region's flora and fauna, as well as for the specific processes governing animal and plant dispersion. Many animals and plants cannot survive or readily disperse into the surrounding [[ecoregion]s], a fact that has accounted for the local distributions, and thus, high numbers of endemic species of this region. Plant endemism has been estimated to reach nearly 10% of the total vegetation. The northern portion of the region, where cacti are abundant, contains 10 of the 14 endemic cacti of the Yucatán Peninsula. The region is considered among Mexico's richest regions in terms of its herpetofauna, because it houses many endemic amphibians and reptiles. The Yucatán dry forests are one of the very few places in Mexico where the Mexican Bearded-lizard (Heloderma horridum) is found, one of only two known venomous lizards on Earth. This ecoregion is home to over 290 bird species (two of which are endemic), as well as approximately 96 mammals.

Mammals include the White-nosed Coatí (Nasua narica), Jaguar (Pantera onca), Central American Spider Monkey (Ateles geoffroyi), and southern opossum (Didelphis marsupialis). Avifauna species include Swainson's warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii), White-fronted Amazon (Amazona albifrons), lesser yellow-headed vulture (Cathartes burrovianus), and hooded warbler (Wilsenia citriha).

Amphibians occurring in the Yucatan dry forests ecoregion are: the Veragua Robber Frog (Craugastor rugosus), which is typically found in leaf litter; the Mexican Treefrog (Smilisca baudinii); the Mexican White-lipped Frog (Leptodactylus labialis); the Cane Toad (Rhinella marina); the Gulf Coast Toad (Incilius valliceps); the Mahogany Treefrog (Tlalocohyla loquax); the Mexican Cascades Frog (Lithobates pustulosus), which is especially known to rocky cascading streams; the Red-eyed Leaf Frog (Agalychnis callidryas); the Rio Grande Frog (Lithobates berlandieri); Sabinal Frog (Leptodactylus melanonotus), which is known for its creation of nests in burrows near ephemeral water bodies; the Stauffer's Long-nosed Treefrog (Scinax staufferi), which is typically found in marshes and savannas; the Yellow Cricket Treefrog (Dendropsophus microcephalus); Yucatan Rainfrog (Craugastor yucatanensis); and the Yucatan Casquheaded Treefrog (Triprion petasatus).

Current status

The Yucatán dry forests have been extensively cleared for agricultural and cattle farming pressures, due to the expanding human population. Many square kilometres of dry forest have been substituted either by henequén plantations, or by secondary communities that arise from intense cattle grazing. The northern portion of the Yucatan contains a unique community of dry forests with abundant columnar cacti. However, this is one of the most damaged areas of dry forests, and is considered as an endangered community of plants that should be protected and saved from extinction. Of fourteen species of cacti that live in the peninsula, only ten are common in this region. The endangered Yucatán cacti is becoming increasingly rare due to the increasing illegal extraction of these plants from their native habitats for trade in national and international markets.

Types and severity of threats

In the state of Yucatán, at least one species of cacti, Pereskipsis scandens, is now considered extinct. Another species, Pterocereus gaumeri, is considered a relic species and is highly endangered. As with the cacti, many species of animals and plants are also facing extinction due to the accelerated loss of habitat in this region. Federal protection should focus on the enforcement of laws against the trade of exotic wildlife species and on regulating soil use. In general, protected areas in the Yucatán region are oriented to the preservation of wetlands, rather than to the dry forests. However, some areas of dry forest have been proposed for protected status. This could be the last opportunity to save many endemic species from extinction in the dry forests of Yucatán.

Justification of ecoregion delineation

These dry forests occupy a large portion of the Yucatan Peninsula, and the southeastern boundary with the moist forest denotes a gradual climatic and subsequent vegetation transition. The linework for the ecoregion follows INEGI vegetation cover maps, from which we lumped the following classifications: "low deciduous forest", "medium deciduous forest", "microphyll desert matorral", "grasslands", and all subsequent agriculture within this broader classification. These dry forest are isolated from similar habitat types, and bound along the northern and eastern portion by the Gulf of Mexico. Several endemic species are known to occur here. Linework was reviewed at ecoregional workshops.

Further reading

- Challenger, A. 1998. Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México. Pasado, presente y futuro. Conabio, IBUNAM y Agrupación Sierra Madre, México.

- CICY. 1993. Jardín Botánico Regional. Guía General. Yucatán, México: Centro de Investigaciones Científicas de Yucatán, A.C.

- CONABIO Workshop, 17-16 September. 1996. Informe de Resultados del Taller de Ecoregionalización para la Conservación de México.

- CONABIO Workshop, Mexico, D.F., November. 1997. Ecological and Biogeographical Regionalization of Mexico..

- Estrada-Loera, E. 1991. Phytogeographic relationships of the Yucatán Peninsula. Journal of Biogeography 18: 687-697.

- Flores-Villela, O. 1993. Herpetofauna de México: distribución y endemismo. Pages 251-279 in T. P. Ramamoorthy, R. Bye, A. Lot, y J. Fa, editors, Diversidad Biológica de México. Orígenes y Distribución. Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Mexico.

- INEGI Map (1996) Comision Nacional Para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) habitat and land use classification database derived from ground truthed remote sensing data Insitituto Nacional de Estastica, Geografia, e Informática (INEGI). Map at a scale of 1:1,000,000.

- Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de Mexico. Editorial Limusa. Mexico, D.F., Mexico.

- Rzedowski, J. pers.comm. at CONABIO Workshop, 17-16 September, 1996. Informe de Resultados del Taller de Ecoregionalización para la Conservación de México.

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE, or for editing of the original content. |