Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley), Egypt

Contents

- 1 Geographical Location

- 2 Dates and History of Establishment

- 3 Area

- 4 Land Tenure

- 5 Altitude

- 6 Physical Features

- 7 Geological History

- 8 Climate

- 9 Vegetation (Modern and Ancient)

- 10 Fauna (Modern and Ancient)

- 11 Cultural Heritage

- 12 Local Human Population

- 13 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 14 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 15 Conservation Value

- 16 Conservation Management

- 17 IUCN Management Category

- 18 Further Reading

Geographical Location

Wadi Al-Hitan (29° 15’ 13 to 29° 23’ 56N by 30° 00’ 41 to 30° 10’ 06 E) is a World Heritage Site in the Western Desert 150 kilometers (km) southwest of Cairo and 80 km west of Faiyum in the Wadi el-Rayan Protected Area.

Dates and History of Establishment

- 1905: Fossil whales first discovered on the site; named Basilosaurus;

- 1970s: Wadi el-Rayan lakes and wetland created by agricultural drainage from Faiyum;

- 1980s: Geologists began to study the whale fossils, naming the area Whale Valley (Wadi Al-Hitan);

- 1989: Wadi el-Rayan Protected Area (WRPA) declared by Prime-ministerial Decree 943 under Law 102 of 1983 on Natural Protectorates;

- 1997: Wadi Al-Hitan included as a Special Protected Area within the Wadi el-Rayan Protected Area by Prime-ministerial Decree 2954.

Area

25,900 hectares (ha), comprising a 20,015 ha core area with a 5,885 buffer zone. The Reserve is entirely within the Wadi El-Rayan Protected Area, no other part of which is nominated.

Land Tenure

State. Managed by the Nature Conservation Sector of the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency.

Altitude

70 meters (m) to 210 m.

Physical Features

The area is in the arid western desert on the westernmost edge of the great depression of Faiyum – Wadi Rayan west of the Nile. The deepest contours of the nearby Wadi Rayan are now occupied by two brackish lakes created in the 1970s from excess agricultural water channeled from nearby Lake Qarun in the Faiyum oasis which has enriched the previously meager wildlife of the area. The totally dry sand-covered Wadi Al-Hitan 40 km west exhibits wind-eroded pillars of rock surrounded by sand dunes, cliffs and remnant hills of a low shale and limestone plateau.

Geological History

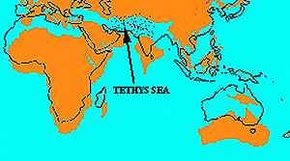

For eons the Tethys Sea reached far south of the existing Mediterranean. It gradually retreated north depositing thick layers of sediments which became sandstone, limestone and shale, seen at Wadi Al-Hitan. Three Eocene formations are visible. The oldest is the Gehannam Formation (ca 40-41 million years old) consisting of white marly limestone and gypseous shale and yielding many skeletons of archaic whales (archaeocetes), sirenians (sea cows), shark teeth, turtles, and crocodilians. The middle unit, Birket Qarun Formation, consists of sandstone, clays and hard limestone, which also yields whale skeletons. The youngest formation is the Qasr El-Sagha Formation of Late Eocene age, about 39 million years old. It is rich in marine invertebrate fauna, indicating a shallow marine environment. These formations were uplifted from the southwest, creating drainage systems, now buried beneath the sand, which emptied to the sea through mangrove-fringed estuaries and lagoons when the coast was near present Faiyum some 37 million years ago.

In Wadi Al-Hitan in an area over 10 km long there has been found an unusually large concentration of over 400 fossil skeletons of archaic whales and other vertebrates, extensively displayed on the desert floor and in cliffs. A few are exposed but most are shallowly buried in sediments, from which erosion slowly releases them. It is expected that further skeletons will be excavated. The site provides evidences of millions of years of coastal marine life. The presence of many baby skeletons suggests that the place was a shallow and nutrient-rich embayment frequented for calving. Since the fossils of different periods lie at different levels they are valuable indicators of palaeogeologic and palaeoecologic conditions, Eocene life, and the evolution of marine mammals.

Climate

The climate is typically Saharan, hot and dry in summer and mild with scanty rain in winter. At nearby Wadi el-Rayan the annual average precipitation is 10.1 millimeters (mm), 40% falling in December. The average ambient relative humidity is 51%. The mean winter temperature is 13.7 degrees Celsius (°C) with an absolute minimum of –1.2°C; the mean summer temperature is 28.5°C with an absolute maximum of 48.4°C; the average diurnal range is 15.6°C. The direction of the wind for most of the year is from the north, varying from northwest to northeast. The Wadi is subject to both [[erosion] and deposition] which buries or exposes the skeletons.

Vegetation (Modern and Ancient)

The present site is extremely barren and there is very little vegetation. Tamarix nilotica is the most prominent shrub, accompanied by the halophytes Salsola imbricata spp.gaetula, Zygophyllum coccineum and Cornulaca monocantha.

Fossil remains of sea grasses and mangroves with clearly exposed vertical pneumatophores were first noticed in the 1920s. Nearby, a worm-bored log was found of a species resembling the mangrove palm Nypa fruticans, a plant of southeast Asia, which suggests that the Eocene climate in the area was humid and warm.

Fauna (Modern and Ancient)

The present day fauna is very sparse. The fennec fox Fennecus zerda has been seen, and mammals found in the WRPA which might occasionally occur are north African jackal Canis aureus lupaster, red fox Vulpes aegyptiaca, Rüppell’s fox V. rueppeli, Egyptian mongoose Herpestes ichneumon, African wildcat Felis sylvestris lybica, and dorcas gazelle Gazella dorcas. 19 reptiles and 36 breeding birds are recorded for the WRPA, mostly attracted by the lakes. Wadi Al-Hitan is not separately noted but the desert species hoopoe lark Alaemon alaudipes, probably occurs.

The nominated site contains a diverse Eocene marine fauna including 25 genera of more than 14 families and 4 classes of vertebrates. They are not the oldest whale fossils but cover a vital [[evolution]ary] period of some 4 million years when these mammals evolved from land to sea-going animals. The fossils which range from young to old individuals in a great concentration of specimens, are so well preserved that even some stomach contents are intact. The neighboring Gebel Qatrani also an exceptionally rich fossil site.

The skeletons of four species of Eocene whales have been uncovered in the highest concentration of such remains in the world: 379 fossil whales (179 cataloged) and 40 cataloged vertebrates. Three of the whales are Basilosaurids, the latest surviving group of archaeocete whales which are the earliest, now extinct, sub-order of whales, ancestors of the modern Mysticeti and Odontoceti whale families. Their fossils reveal the evolution of whales from land and shore-based to ocean-going mammals. Though they retained certain primitive aspects their form was already streamlined. The largest was Basilosaurus isis, which was up to 21 m long, with well developed five-fingered flippers on the forelimbs and the quite unexpected presence of hind legs, feet, and toes, not known previously in any archaeocete; a vestigial use may have been as claspers during aquatic mating. Their form was serpentine and they were carnivorous. Many infant skeletons were also found. These and the dense congregation are probably due to the area having been shallow and nutrient-rich and therefore used for calving by the animals.

Another species is Dorudon atrox, also found with vestigial hind limb bones, a small whale with a more compact dolphin-like body. The presence of calving females of this species may have attracted the larger predator whales. Other whales found are Saghacetus osiris and Anclacetus simonsi. Nineteen other species of vertebrates are known: three species of early sirenian (sea cow), one partial skeleton of the primitive proboscidian Moeritherium, early mammals, sharks, crocodiles, three kinds of sawfish, rays, cartilaginous and bony fishes, several kinds of turtles, including a sea turtle and a sea snake. There is a rich invertebrate fauna with thousands of remains, large and small, of nummulites, molluscs, gastropods, bivalves, echinoids and crabs, which, with the remains of plants, permit reconstruction of the ecology and habitat of the animals.

Cultural Heritage

Wadi Al-Hitan itself was probably always rather abandoned in historical times. However, the ancient Lake Moeris in the nearby Faiyum depression was large and the climate 8,500-4,000 years ago was wetter, so the abundant wildlife and surrounding fertile soils, attracted continuous human habitation to the Faiyum area from Neolithic times to the present. It was also a major crossroad used for many centuries by travelers between the Nile Valley and the oases of the Western Desert. Remains of human settlements from the early Egyptian, Greek and Roman eras are found there.

Local Human Population

No-one lives on the site, but Wadi el-Rayan 40 km away has a few thousand settled and temporary farmers and fishermen.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

From 1997 on, Wadi el-Rayan became a popular excursion area for Cairenes and in 2003 a well equipped Visitors’ Centre with an audio-visual theater and fossil museum was sited on the western lakeshore. Brochures, a video and a website have been produced for the Wadi site. Only about 1,000 visitors a year drive on to Wadi Al-Hitan as the 4WD track is unpaved, crosses treacherous sands and the site itself is extreme desert. Because the area has had to be protected, the management plan for the Wadi el-Rayan Protected Area is applied to Wadi Al-Hitan restricting visitors to prearranged guided tours along a prescribed trail either on foot or by camel. Sustainable tourism is beginning to be developed and tourism will increase in the future.

Scientific Research and Facilities

The first fossil whale was found in the Faiyum oasis in the 19th century. Large fossil skeletons were first found in Wadi Al-Hitan in the winter of 1902-3 and named Zeuglodon by Beadnell of the Geological Survey of Egypt. This find was followed by Andrews of the Natural History Museum, London who in 1905 renamed it Basilosaurus isis on the assumption that it was a dinosaur, and named a second find Dorudon atrox. Two brief unpublished visits by the University of California and Yale University followed in mid century. But between 1985 and 1993 P. Gingerich from the University of Michigan discovered hundreds of fossils, among them, in 1989, the last whales found with functioning feet, 10 million years after their evolution from terrestrial to marine existence. In the dense aggregation they also found many infant skeletons probably because the area being shallow and nutrient-rich was used for calving by the animals. Field work is planned to resume in 2005 and further discoveries are certain.

Specimens from Wadi Al-Hitan are currently displayed in several institutions: 56 specimens, including the type specimens, are preserved in the Cairo Geological Museum; others are held in London, Berlin, Stuttgart and the University of Michigan where there is a complete Dorudon atrox skeletal mount on exhibit. A research plan for the property during 2005-2008 has been developed in a Memorandum of Understanding between EEAA, the University of Michigan, the Egyptian Geological and Mining Surveys. This provides for regulated scientific exploration and specimen collection, curation by the Egyptian Geological Museum and the University of Michigan and training of Egyptian staff.

Conservation Value

Wadi Al-Hitan is of international value as it represents an outstanding record of Middle to Late Eocene life and geological evolution. It is the only place in the world where the skeletons of families of archaic whales can be seen in their original geological and geographic setting of the shallow nutrient-rich bay of an early sea of some 40 million years ago. There is no other place in the world yielding archaic whale fossils of such quality in such abundance and concentration. Many of the sirenians and cetaceans are preserved as virtually complete articulated skeletons which, uniquely, preserve reduced hind limbs, making them intermediate between earlier land mammals and later modern whales. The nominated area contains most of the key interrelated and interdependent elements in their natural relationships which provide a robust foundation for reconstructing the mosaic of paleoenvironments and palaeogeography of a southern [[coast]al] realm of the ancient Tethyan Ocean during Eocene time, enabling interpretation of how animals then lived and how they were related to each other. The high number, concentration and state of preservation of these fossils is unequaled. They are of iconic value for the study of evolutionary transition, and make the site vitally important.

Conservation Management

The nominated property is managed as a Special Protection Zone within the Wadi El-Rayan Protected Area (WRPA). The 2002-2006 Management Plan for the WRPA was applied to Wadi Al-Hitan, restricting visitors to the site to guided tours along a marked trail and proscribing many activities. These include the destruction of geological formations, discharging pollutants, hunting and littering. The Wadi Al-Hitan site is patrolled daily to catch illegal visitors and twice a week a team monitors the condition of the fossils, photographing them and when necessary repairing damage. To ward off 4WD intruders, staff from neighboring tribes are to be trained as guards and tourist guides, and local people will participate in the area’s management. Motorcycle patrols and camel supply transport are proposed. A field outpost is to be sited in excavated caves for protection from the extreme conditions. An open-air museum, two camping sites, camel tours and a bedouin-style ecolodge supplied by private ecotourist companies are all projected, and a sustainable source of funds will be sought.

Management Constraints

The exposed skeletons are fragile. They are vulnerable to wind erosion and burying by wind-carried sand, although fresh fossils are also exposed by the same process. They are more at danger from collectors who steal bones and fossil wood as souvenirs and saleable curiosities, As tourism increases visitors will require constant surveillance and monitoring. The wild landscape is scarred by 4WD tracks which are kept to a minimum. A long-term threat to the Wadi El-Rayan area is the drying up of the artificial lakes by evaporation.

Comparison with Other Sites

Fossil whale sites

Whales evolved from land mammals during early Eocene times, which started some 55 million years ago. By the end of the Eocene 33 million years ago modern toothed and baleen whales existed in virtually their modern form. Thus Wadi Al-Hitan, with its Archaeoceti or archaic whales at 40-37 million years before the present, presents vital evidence of the transition from land mammals to modern ocean-going whales. The intermediacy of the archaeocete whales of Wadi Al-Hitan is corroborated by skeletal features like the retention of well-formed hind limbs, feet, and toes in Basilosaurus and in Dorudon. Wadi Al-Hitan is the only place in the world where numerous archaeocete skeletons can be seen in place in their original geological and geographic setting.

Older and more primitive archaeocete whales come primarily from India and Pakistan from forested foothills of the Himalaya, from desert areas in Kutch, and from desert in tribal parts of Punjab, the Northwest Frontier and Balochistan provinces that are inaccessible to most people. Important older whale sites near Gebel Mokattam in Cairo are now covered by the developing city. A substantial number of partial skeletons of archaeocete whales more or less contemporary with those of Wadi Al-Hitan have been found on the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plain of eastern North America over the past 150 years, but none of these skeletons are complete and the sites where they were found are scattered, covered by vegetation, and generally inaccessible.

Fossil whales of the suborders Mysticeti and Odontoceti are known in abundance from Miocene and Pliocene sites like the 12-15 million-year-old Shark-Tooth Hill in the Temblor Formation of California and the 5-6 million-year-old Cerro Blanco in the Pisco Formation of Peru but the whales from these sites are essentially modern.

Other Palaeontological sites with World Heritage designation

Wadi Al-Hitan with its excellent preservation and abundance of coastal to marine fossil record and sedimentary facies provides an outstanding window on Eocene life evolution and palaeogeography comparable and complementary to Messel Pit Fossil Site in Germany with its dominantly terrestrial record. In the wealth of its deposits, Wadi Al-Hitan is most similar to the Triassic Ischigualasto/ Talampaya Natural Parks site in Argentina, Monte San Giorgio in Switzerland, the Cretaceous Dinosaur Provincial Park in Canada and the Oligo-Miocene fossils of the Australian Fossil Mammal sites. There are very rich deposits of the Burgess shale in the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks and Miguasha National Park in Canada, but these are Palaeozoic; also the Jurassic Dorset and East Devon Coast of the U.K., and the Quaternary deposits of Lake Turkana National Parks in Kenya. The concentration of fossils at Wadi Al-Hitan, and public interest in the site nationally and internationally, are comparable to each of the sites already on the World Heritage List.

An off-site occurrence of the Eocene-Oligocene Gebel Qatrani formation north of Lake Qarun within the Lake Qarun Protected Area have revealed the fossils of ancestral elephants, a two-horned mammal Arsinotherium, and eight primate lineages, including two genera of the earliest known hominoids. It has been called ‘the most complete record of palaeogene mammals for all Africa. It is adjacent, of a similar nature to, and with the same management as Wadi Al-Hitan. As such, there is a strong case for any nomination to be eventually extended to include it. This site has the world’s highest concentration of the fossilized skeletons of archaic whales. They are evidence of many millions of years of [[coast]al] life in the shallow nutrient-rich bay of an early sea. The fossils of different periods and levels are valuable clues to its past geologic and geomorphic processes, its Eocene vertebrate and invertebrate life and the evolution of modern cetaceans 40 million years ago.

Staff

The present staff of 28 rangers and guards is part of the Wadi el-Rayan force. Only one paleontologist-ranger is at present solely working in Wadi Al-Hitan. In time 6 guards working in shifts plus two environmental researchers will staff the outpost.

Budget

The Italian-Egyptian Environment Program, supported by technical assistance from the IUCN, funded the WRPA from 1998-2001 and during Phase II (2004-2008) is committed to fund development at Wadi Al-Hitan with E£6 million (US$518,000). Future funding is expected from government grants, entry fees, donations, and eventually from a Conservation Fund. The projected total expenses for the whole WRPA are given but sums for Wadi Al-Hitan are not stated separately.

IUCN Management Category

- Wadi el-Rayan Protected Area: VI; Managed Resource Protected Area

Further Reading

- Badman, T. (2005). World Heritage Nomination IUCN Summary: Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley), (Egypt). IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Brand, L. (2004). Taphonomy of Fossil Whales in the Miocene/Pliocene Pisco Fm., Peru. PhD Dissertation, Department of Earth and Biological Sciences, Loma Linda University, CA. U.S.A.

- Buena Vista Museum (2001). Sharktooth Hill. Buena Vista Museum, Bakersfield, CA, U.S.A.

- Dolson, J. et al. (2002). The Eocene and Oligocene Palaeo-Ecology and Palaeo-Geography of Whale Valley and Fayoum Basins. Field trip No.7. Rising Star Energy Publications Ltd., Egypt. 79pp.

- Egyptian National Commission for UNESCO et al. (2004). Nomination File for the Inscription of Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley), the Western Desert of Egypt, on the World Heritage List. A bibliography of 30 references

- Gingerich, P. (1992). Marine mammals (Cetacea and Sirenia) from the Eocene of Gebel Mokattam and Fayum, Egypt: stratigraphy, age and paleoenvironments. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 30:1-84.

- Matravers-Messana G. (2002). Wadi el-Rayan: Gateway to the Western Desert. Wadi el-Rayan Protection Project, Egypt. 99pp.

- Redfern, R. (2002). Origins: the Evolution of Continents, Oceans and Life. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London. 360pp. ISBN: 0806133597.

- Wells, R. (1996). Earth’s geological history – a contextual framework for World Heritage site nominations. In Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites. IUCN, Switzerland. 43pp.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

1 Comment

Peter Howard wrote: 02-02-2011 19:49:17

Readers may want to visit the African Natural Heritage website to view a selection of images and map of the Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley) world heritage site, and follow links to Google Earth and other relevant web resources: http://www.africannaturalheritage.org/Wadi-Al-Hitan-Whale-Valley-Egypt.html