Lake Turkana National Parks, Kenya

Contents

- 1 IntroductionLake Turkana National Parks (Sibiloi, Central Island, and South Island National Parks) are World Heritage Sites located between 3°39’-4°00'N and 36°11’-36°34'E, 3°30’N and 36°02’E, and 2°23'N-36°44'E, respectively. Lake Turkana is the largest, most northerly and most saline of Africa's Rift Valley lakes and an outstanding laboratory for the study of plant and animal communities. The three National Parks are a stopover for migrant waterfowl and are major breeding grounds for the Nile crocodile and hippopotamus. The Koobi Fora deposits are rich (Lake Turkana National Parks, Kenya) in pre-human, mammalian, molluscan and other fossil remains and have contributed more to the understanding of palaeoenvironments than any other site on the continent.

- 2 Geographical Location

- 3 Date and History of Establishment

- 4 Area

- 5 Land Tenure

- 6 Altitude

- 7 Physical Features

- 8 Climate

- 9 Vegetation

- 10 Fauna

- 11 Cultural Heritage

- 12 Local Human Population

- 13 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 14 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 15 Conservation Value

- 16 Conservation Management

- 17 IUCN Management Category

- 18 Further Reading

IntroductionLake Turkana National Parks (Sibiloi, Central Island, and South Island National Parks) are World Heritage Sites located between 3°39’-4°00'N and 36°11’-36°34'E, 3°30’N and 36°02’E, and 2°23'N-36°44'E, respectively. Lake Turkana is the largest, most northerly and most saline of Africa's Rift Valley lakes and an outstanding laboratory for the study of plant and animal communities. The three National Parks are a stopover for migrant waterfowl and are major breeding grounds for the Nile crocodile and hippopotamus. The Koobi Fora deposits are rich (Lake Turkana National Parks, Kenya) in pre-human, mammalian, molluscan and other fossil remains and have contributed more to the understanding of palaeoenvironments than any other site on the continent.

Geographical Location

Sibiloi National Park is on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana (formerly Lake Rudolf) 720 kilometers (km) north of Nairobi in between 3°39’-4°00'N and 36°11’-36°34'E. Central Island is midway down L.Turkana in Rift Valley Province at 3°30’N and 36°02’E. South Island is at the southern end of the lake, at 2°23'N-36°44'E. The park extends 1 km out from the island’s shore.

Date and History of Establishment

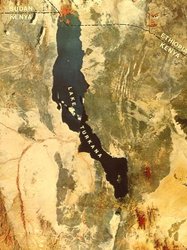

Composite satellite image of Lake Turkana. (Source: Rutger's University Turkana Basin Paleo Community)

Composite satellite image of Lake Turkana. (Source: Rutger's University Turkana Basin Paleo Community) - 1973: Sibiloi established as a National Park by legal notice #160.

- 1978: Mount Kulal Biosphere Reserve set up beside southeast Lake Turkana: the Reserve includes the waters of Lake Turkana, also South Island.

- 1983: Central and South Islands gazetted as National Parks (Gazette notices #18 and 12).

Area

161,485 hectares (ha). Sibiloi: 157,085 ha. Central Island: 500 ha. South Island: 3,900 ha.

Land Tenure

Kenyan Wildlife Service, in Marsabit District of the Eastern Province. Administered by the Kenyan Wildlife Service.

Altitude

375 meters (m) to 550 m.

Physical Features

Lake Turkana occupies the beds of two grabens at the northern end of the Kenyan Great Rift valley in barren desert country. It is the largest and most northerly of all the Rift Valley lakes, with a delta extending into Ethiopia and measuring 249 km by 48 km at its widest. It has three volcanic islands, north, central and south: Central Island is a small active volcano with three saline crater lakes; South Island measures 11 x 4.5 km. 98% of the lake’s water comes from Ethiopia via the Omo River, and most of the rest from two southern tributaries, the Kerio and the Turkwel, which is being dammed. There is no outflow and with reduced inflows and high evaporation the chloro-carbonate alkaline water is subject to marked 3 - 4 m seasonal fluctuations in level and is becoming increasingly saline though it is drinkable. The level dropped 10 m between 1975 and 1992. Its striking jade-green color is due to the presence of blue-green algae Microcystis aeruginosa in the phytoplankton. The lake shore is mostly rocky or sandy, with little vegetation. The borders of all the Parks extend 1 km off shore into the lake. Rich fossiliferous deposits are found for 60 km north from Allia Bay and to 20 km inland. The plains are flanked by volcanic formations including Mount Sibiloi, the site of the remains of a petrified forest estimated to have grown seven million years ago.

Climate

The climate is very hot, arid and very windy. The air temperature ranges between 19.2° and 39.9 degrees Celsius (°C) with a mean daily temperature range of 31°C-33°C. The months of October to January are the warmest and driest, July and August, the coolest. During this period the area is subject to the frequent and strong southerly and southeasterly winds. The total annual rainfall is less than 200 millimeters (mm) and is unpredictable though most likely between March and May. It may not rain for years, and the long drought between October 1998 and May 2001 was very destructive, especially of trees taken for fuelwood and charcoal.

Vegetation

Remoteness has preserved the area as a natural wilderness. On the grassy plains yellow speargrass Imperata cylindrica, Commiphora sp.,Acacia tortilis, and other acacia species predominate along with A. elatior, desert date Balanites aegyptiaca and doum palm Hyphaene coriacea in sparse gallery woodlands. Salvadora persica bush is found on Central and South Islands. The northeastern shore of the lake is mostly rocky or sandy. The muddy bays of South Island have extensive submerged beds of Potamogeton pectinatus which shelter spawning fish. The principal emergent macrophytes in the seasonally exposed shallows are the grasses Paspalidium geminatum and Sporobolus spicatus.

Fauna

Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). (Source: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Photograph by Christopher Jameson)

Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). (Source: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Photograph by Christopher Jameson) Despite the low carrying capacity of the area the fauna is relatively diverse, especially in breeding and migrant birds. The island parks were established to protect the breeding habitats of the Nile crocodile Crocodylus niloticus, hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius, puff-adder Bitis arietans, cobra Naja haje and sawscaled viper Echis pyramidum. The lake is an important flyway for migrant birds. Over 350 species of aquatic and terrestrial birds are known for the region, which is recognized by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area, and a priority for conservation. On South Island 220,000 waterbirds of 84 species have been recorded with 34 Palaearctic migrants. As recorded in 1992 by Bennin & Njoroge key species making up 1% or more of the population include the pink-backed pelican Pelecanus rufescens (1,060), greater flamingo Phoenicopterus rubra (3.000), Spur-winged plover Vanellus spinosus (6,930), ringed plover Charadrius hiaticula (13,600), Caspian plover C. asiaticus (500), Kittlitz's plover C. pecuarius (8,600) and little stint Calidris minuta (113,000). At least 23 bird species are known to breed in the environs of the lake, including the goliath heron Ardea goliath. Regionally threatened bird species in the area include great egret Casmerodius albus (60), saddle-billed stork Ephipiorhynchus senegalensis (9), banded snake eagle Circaetus cinerascens, fish eagle Haliaeetus vocifer, fox kestrel Falco alopex, African skimmer Ryncops flavirostris (50) and Somali sparrow Passer castanopterus. The site is also an important staging post for migrating warblers and wagtails.

Mammals in the area include olive baboon, Papio anubis, wild dog, Lycaon pictus, striped hyaena Hyaena hyaena, caracal Caracal caracal, lion Panthera leo and cheetah Acinonyx jubatus, plains and Grevy's zebras Equus burchelli and E. grevyi, warthog Phacocoerus aethiopicus, hippopotamus, Grant's gazelle Gazella granti, reticulated giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata, Beisa oryx Oryx gazella beisa, hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus, topi Damaliscus lunatus korrigum, greater kudu Tragelaphus strepticeros, lesser kudu T. imberbis, gerenuk Litocranius walleri and dikdik Rhyncotragus guntheri. 47 fish species, seven being endemic, live in the lake. These fish support the world's largest populations of Nile crocodile: approximately 14,000 breed on Central Island.

Cultural Heritage

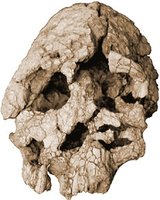

At Koobi Fora to the north of Alia Bay, extensive palaeontological finds have been made, starting in 1972 with the discovery of Homo habilis. These are evidence of the existence of a relatively intelligent hominid two million years ago and reflect the change in climate from moist forest grasslands when the now petrified forests were growing to the present hot desert. The human and pre-human hominid fossils include the remains of four species, the most important being the 1999 discovery of 3.5-million year old Kenyanthropus platyops. Other findings include several ancestors of modern animal species. Over 100 archaeological sites have been discovered so far. This is the only archaeological conservation area in Kenya gazetted as a national park.

Local Human Population

There are no residents in Sibiloi and Central Island National Parks, but Gabbra, Rendille and Turkana pastoralists are permitted to bring cattle and goats into the Park during the dry season. South Island Park is in the center of land inhabited by the El-Molo tribe of fishermen, whose numbers recovering but are still only 500 individuals.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

Kenyanthropus platyops skull. (Source: Michigan State University)

Kenyanthropus platyops skull. (Source: Michigan State University) Very few visitors travel to these National Parks although their tourist potential is quite high. Visitors to Sibiloi and Central Island Park during 1992-1998 range from 1,294 in 1996 to 458 in 1998, with more people visiting Sibiloi. There are camping facilities at the Koobi Fora museum and at Rocodoni facing Mount Sibiloi, but visitors must bring their own supplies. There are three hotels; Oasis Lodge at Loiyangalani at the southeast end of the lake, provides a base and motor boats for visitors to travel to South Island Park for bird watching.

Scientific Research and Facilities

Extensive archaeological work has been done in the area by Richard Leakey and many others, and is ongoing. Very important ancestral human fossils have been recorded from the area, including the remains of Australopithecus robustus, Homo habilis, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Fossils of other African mammals have also found there: black and white rhinoceros, extinct giant otter, hippopotamus, pygmy hippopotamus, African elephant and camel. Although there is no formal and systematic monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment) program for the Lake Turkana sites, KWS, the National Museums of Kenya and the Department of Resource Surveys and Remote Sensing carry out some monitoring in the Parks. Public and private universities provide expertise in research, monitoring and impact assessment. A survey of birds was undertaken in 1992. The Kenyan Wildlife Service Training Institute, in Naivasha, and the Mweka African College of Wildlife Management in Moshi, Tanzania, are valuable training centers for wardens and rangers working in the region.

Conservation Value

These remote parks are globally of great value for terrestrial and aquatic conservation, especially for waterbirds. South Island Park in particular has been identified as an Important Bird Area and a priority site for biodiversity conservation. Population counts in 1992 recorded over 220,000 waterbirds. The establishment of protected areas around Lake Turkana which includes an adjacent Biosphere Reserve (Mount Kulal) extending over the waters of the lake, provides an extensive and valuable conservation network.

Conservation Management

The Kenyan Wildlife Service manages protected areas in Kenya and has agreed memoranda of understanding with the National Museums of Kenya for the conservation of fossil sites, with the Kenyan Fisheries Department for lake fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture) and the Kenya Forestry Department for catchment [[forest]s], especially for managing South Island National Park. However, local people are allowed to use areas in Sibiloi and Central Island National Parks during the dry season (December-March). A five year Integrated Management Plan has been developed for Lake Turkana and its national parks with assistance from the UNESCO World Heritage Fund. Its goals are conservation of the archaeological sites, park habitats and biodiversity. Its objectives are to promote environmental awareness, education and ecotourism, scientific research and monitoring (Environmental monitoring and assessment), collaboration with stakeholders and to alleviate poverty.

Management Constraints

The area's protection is largely nominal but because of its remoteness, there is relatively little direct pressure on the environment. However, local people are beginning to become more sedentary, increasing the grazing pressure from livestock which is now becoming a problem particularly along the shores of Lake Turkana. It also causes unauthorized trespassing into the Park and increased soil erosion in the strong winds of the area. The collection and cutting of Salvadora persica by local fisherman is also exposing soil to erosion. Pressure on fish [[population]s] in the lake is increasing, although attempts to introduce industrial scale fishing projects have so far failed. Birds nesting on South Island have been disturbed in recent years by fisherman. The water level of the lake has been dropping steadily for some years: a decline of 10 m was recorded between 1975 and 1993, primarily due to reduced inflow from the Omo River in Ethiopia due to irrigation and drought upstream. Upstream irrigation and a hydropower dam also affect the supply from the Turkwel. A severe drought in 1999-2000 led to loss of livestock, wildlife and starvation.

Staff

The three Lake Turkana Parks are managed by a workforce of forty-three: one warden, 22 rangers, and 12 support staff.

Budget

Funding for the protected areas comprising the nominated site come from central government, donors and from visitor fees. In 1996 funding for the Lake Turkana ecosystems amounted to US $50,000. The Provisional Integrated Management Plan stated a 5-year tentative budget of US$335,000.

IUCN Management Category

- II Sibiloi / Central Island National Parks II South I.National Park. BiosphereReserve (part)

- Natural World Heritage Site Natural Criteria i, iii, iv (Sibiloi), ii, iii, iv (South I.)

- Inscribed in 1997 (Sibiloi & Central Island) and 2001 (South Island).

Further Reading

- Bennun, L. & Fasola, M. (eds.) (1996). Resident and migrant waterbirds at Lake Turkana, February 1992. Quarderni della Civica Stazione Idrobiological di Milano, 21: 7-62.

- Bennun, L.& Njoroge, P. (2001). Kenya. pp.411-464 in Fishpool, L.& Evans,M.(eds) (2001). Important Bird Areas for Africa and Associated Islands. Priority Sites for Conservation. Pisces Publications and Birdlife International, Newbury and Cambridge, U.K. BLI Conservation Series No.11.

- Cunningham Van-Someren, C. (1981). Lake Turkana Biological Survey: Birds. Report to the National Museum of Kenya, Nairobi.

- Fasola, M., Biddau, L., Borghesio, L., Bacetti, N. & Spina, F.(1993a). Waterbird populations at Lake Turkana, February 1992. Proc.Pan-Afr.Orn. Cong. 529-532.

- Fasola, M., Biddau, L.& Borghesio, L., (1993b). Habitat preference of resident and Palaearctic waterbirds of Lake Turkana. Proc.Pan-Afr.Orn. Cong. 539-545.

- Fishpool, L.& Evans, M. (eds) (2001). Important Bird Areas for Africa and Associated Islands. Priority Sites for Conservation. Pisces Publications and Birdlife International, Newbury and Cambridge, U.K. BLI Conservation Series No.11.

- Fitzgerald, M. (1981). Sibiloi: the remotest park in Kenya. Africana 8(4): 22.

- Government of Kenya. 1994. National Environment Action Plan. Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Hopson, A. (ed.) (1982). Lake Turkana: a Report of the Findings of the Lake Turkana Project. 1972-75 Six volumes. London. Overseas Development Administration. ISBN: 0901636460.

- International Lake Environment Committee (ILEC). (2002). World Lakes Database. Lake Turkana.

- Kenyan Fisheries Department (KFD) (n.d.). Aquatic Ecosystems. Lake Turkana. Kenyan Fisheries Department.

- Kenya Wildlife Service (1996). Nomination Forms for Maasai Mara World Heritage Site, Mount Kenya World Heritage Site and Sibiloi World Heritage Site. Kenya Wildlife Service, Nairobi, Kenya.

- (2001). Nomination Form for The Great Rift Valley Ecosystems Sites. Extension of Lake Turkana: South Island National Park. Nairobi.

- Metzger, B. (1996). Kenya Travel Handbook. Kenya Tourism Foundation. 208pp.

- Njuguna, S. (2001). Provisional Integrated Management Plan 2001-2005. SPARVS Agency for the Kenya Wildlife Service. 18pp.

- Republic of Kenya. (1985). Turkana District Resources Survey 1982-1984. Main Report. Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Energy and Regional Development.

- Schekkerman, H. & van Wetten, J. (1987) An Ornithological Winter Survey of Lake Turkana, Kenya. WIWO Report No.7. Zeist, Netherlands. Dutch Working Group on International Wader and Waterfowl Research.

- Willcock, C. (1974). Africa's Rift Valley. Time-Life Books (Nederland), B.V. Amsterdam. 184pp.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

1 Comment

Peter Howard wrote: 02-02-2011 20:02:23

Readers may want to visit the African Natural Heritage website to view a selection of images and map of the Lake Turkana National Parks world heritage site, and follow links to Google Earth and other relevant web resources: http://www.africannaturalheritage.org/Lake-Turkana-National-Parks-Kenya.html