Sri Lanka montane rain forests

The number of known floral and faunal endemic species of the Sri Lanka Montane Rain Forests is higher than in the lowland rain forests, which are also renowned for high levels of endemism. But new ongoing surveys that have focused on the hitherto neglected secretive fauna reveal a plethora of additional new species (Biodiversity) limited to the montane forests. These surveys demonstrate that this area's biodiversity is even more important globally than previously thought.

The known levels of endemism apparently are only the tip of the iceberg. In light of the emerging information, the Sri Lanka Montane Rain Forests can be considered a super-hotspot within the endemism hotspot of global importance recognized by Myers et al.

Location and General Description

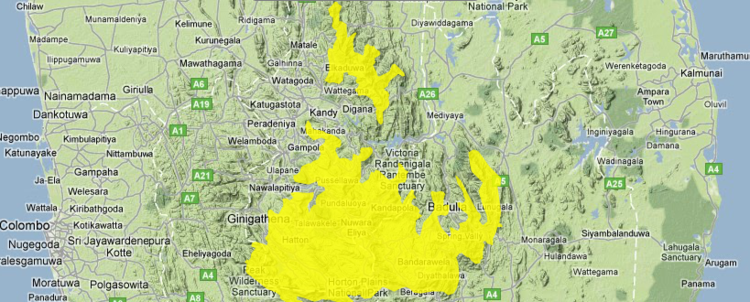

The Sri Lanka Montane Rain Forests represents the montane and submontane moist forests above 1,000 meters (m) in the central massif and in the Knuckles Mountain Range to the northeast.

Sri Lanka first separated from the Deccan Peninsula during the late Miocene, but geologically it has Gondwanaland origins. The biogeographic patterns indicate that the wet forests in the southwestern quarter became isolated from the nearest other wet forests in the mainland soon after the first separation when climatic changes created drier, warmer conditions throughout most of the lowland areas. During subsequent Pleistocene-period land-bridge connections, the intervening drier habitat prevented the exchange of wet forest-adapted species with the wet forests in India. Therefore, the species in the southwestern quarter evolved and speciated in isolation, giving rise to the high levels of endemism that are evident today.

The post-Miocene uplift that created three peneplains, or steep plains of erosion, have also served as biogeographic barriers, isolating taxonomic groups. This is best exemplified in the distribution of the freshwater fish fauna, where the lowland streams have the highest species richness, the second peneplain fewer, and the upper peneplain streams support a limited fish fauna. Floral surveys also show that plant diversity is greater in the lowland forests but that the montane forests support greater numbers of endemic plants.

The higher peaks of the central massif attain heights of more than 2,500 m, but the average height is about 1,800 m. The isolated Knuckles Range to the northwest of the central massif rises to more than 1,800 m, but the main range is about 1,500 m. All of Sri Lanka's major rivers originate in the central mountains and radiate outward. The predominant soil type is red-yellow podzolic soils.

There is a general trend of a 0.5 degrees Celsius (oC ) decrease in air temperature for every 100-m rise in elevation; therefore, the climate is cooler than in the lowlands. Ground frost is not uncommon in the higher elevations during the nights from December to February. Many of the high peaks are also enveloped in mist and fog, creating cloud forests.

The ecoregion receives 2,500-5,000 millimeters (mm) of annual rainfall. Most of the rainfall is from the May to September southwestern monsoon, which expends its moisture on the western, windward side. The northeastern monsoon, which sweeps in from the northeastern coast and ascends the gentler eastern slopes, brings additional rainfall to the ecoregion from December to March.

The vegetation is influenced primarily by climate and ranges from Dipterocarpus-dominated montane moist forests to montane savanna and cloud forests with Rhododendron species. The submontane forests in the central massif are dominated by a Shorea-Calophyllum-Syzygium community with a canopy of Shorea gardneri, S. trapezifolia, Palaquium spp., Homalium zelanicum, Calophyllum calaba, C. tomentosum, C. pulcherrimum, Syzygium spp., Cullenia spp., Myristica dactyloides, Cryptocarya wightiana, and Neolitsea involucrata. The forests above 1,500 m are composed of twisted, stunted Syzygium-Gordonia-Michelia-Elaeocarpus formations, draped in a rich epiphytic community of orchids, mosses, and filmy ferns, and a Strobilanthes-dominated understory. Other prominent genera include Cinnamomum, Litsea, Neolitsea, Symplocus, Semecarpus, Carallia, Garcinia, and Mastixia. The montane forests of the Peak Wilderness area have forests that are locally dominated by the endemic Dipterocarpaceae genus Stemnoporus, possibly representing the only area of a dipterocarp-dominated montane forest, but in general the montane forests are dominated by Lauraceae, Myrtaceae, Clusiaceae, and Symplocaceae. Rhododendron species occur at the highest elevations-where cloud forests prevail-and in the transition zones with the wet montane grasslands, locally known as wet pathanas. These grasslands are thought to be fire-maintained and support a rich herb community with both temperate and tropical elements. Several animal species have also adapted their life history and behavior (e.g., nesting patterns) to these fire regimes. Not too long ago, Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) roamed these savannas, although they have now become locally extinct.

The flora of the detached Knuckles Range is different from the central massif flora and is characterized by a Myristica-Cullenia-Aglaia-Litsea community with subtropical affinities and a tropical Callophyllum zone.

Biodiversity Features

The montane forests harbor higher levels of endemism than the lowland ecoregion. Half of Sri Lanka's endemic flowering plants and 51 percent of the endemic vertebrates are limited to this ecoregion. The smaller, isolated Knuckles Range has several species (Biodiversity) of relict, endemic flora and fauna that are distinct from the montane forests of the central massif.

More than 34 percent of Sri Lanka's endemic trees, shrubs, and herbs are limited to the montane rain forests represented by this ecoregion.

The ecoregion harbors eight near-endemic mammals, and five are strict endemics (Table 1). Two genera, Srilankamys and Feroculus, are monotypic and are strictly endemic to this ecoregion.

|

| |

|

Family |

Species |

|

Soricidae |

Suncus montanus |

|

Soricidae |

Feroculus feroculus* |

|

Soricidae |

Crocidura miya* |

|

Soricidae |

Solisorex pearsoni* |

|

Cercopithecidae |

Semnopithecus vetulus |

|

Viverridae |

Paradoxurus zeylonensis |

|

Sciuridae |

Funambulus layardi |

|

Sciuridae |

Funambulus sublineatus |

|

Muridae |

Petinomys fuscocapillus |

|

Muridae |

Mus fernandoni |

|

Muridae |

Vandeleuria nolthenii |

|

Muridae |

Rattus montanus* |

|

Muridae |

Srilankamys ohiensis* |

|

An asterisk signifies that the species' range is limited to this ecoregion. | |

This ecoregion also supports a population of the Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) recognized by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) as a threatened genotype. The leopard is also the largest carnivore in Sri Lanka. Other endangered species include the endemic Rattus montanus and five shrews: Crocidura miya, Feroculus feroculus, Solisorex pearsoni, Suncus fellowsgordoni, and Suncus zeylanicus.

The Sri Lanka Montane Rain Forests ecoregion is included within an EBA, Sri Lanka (124). The ecoregion harbors twenty near-endemic bird species, of which five are strict endemics (Table 2).

|

| ||

|

Family |

Common Name |

Species |

|

Columbidae |

Ceylon wood-pigeon |

Columba torringtoni |

|

Bucconidae |

Ceylon grey hornbill |

Ocyceros gingalensis |

|

Cuculidae |

Red-faced malkoha |

Phaenicophaeus pyrrhocephalus |

|

Phasianidae |

Ceylon junglefowl |

Gallus lafayetii |

|

Corvidae |

Ceylon magpie |

Urocissa ornata |

|

Sturnidae |

White-faced starling |

Sturnus senex |

|

Sturnidae |

Ceylon myna |

Gracula ptilogenys |

|

Timaliidae |

Orange-billed babbler |

Turdoides rufescens |

|

Turdidae |

Ceylon whistling-thrush |

Myiophonus blighi* |

|

Muscicapidae |

Dull-blue flycatcher |

Eumyias sordida* |

|

Pycnonotidae |

Yellow-eared bulbul |

Pycnonotus penicillatus* |

|

Zosteropidae |

Ceylon white-eye |

Zosterops ceylonensis* |

|

Sylviidae |

Ceylon bush-warbler |

Bradypterus palliseri* |

|

Turdidae |

Spot-winged thrush |

Zoothera spiloptera |

|

Muscicapidae |

Kashmir flycatcher |

Ficedula subrubra |

|

Timaliidae |

Brown-capped babbler |

Pellorneum fuscocapillum |

|

Capitonidae |

Yellow-fronted barbet |

Megalaima flavifrons |

|

Psittacidae |

Ceylon hanging-parrot |

Loriculus beryllinus |

|

Psittacidae |

Layard's parakeet |

Psittacula calthropae |

|

Strigidae |

Chestnut-backed owlet |

Glaucidium castanonotum |

|

An asterisk signifies that the species' range is limited to this ecoregion. | ||

Despite years of biological exploration, new species are still being discovered in this ecoregion, especially within the concealed fauna, such as the frogs, lizards, fishes, and crabs. In addition to the large number of Rhacophorid frogs, new species have been added to the endemic agamid lizard genera, Lyriocephalus, Ceratophora, and Cophotis, over the past few years. Dedicated surveys of the crab fauna have increased the number of described species from seven in 1993 to thirty-five, some of which represent endemic genera. Undoubtedly many more of these secretive yet fascinating species await discovery in this ecoregion.

Current Status

Over the past 200 years, most of the montane rain forests have been cleared to establish large tea (Camellia sinensis) plantations. Therefore, we will never know the full extent of the endemic biodiversity that has been lost forever, although the localized distribution patterns of species provide some indication of what this ecoregion's forests may have held.

Because many of the endemic species have specialized habitat needs and small spatial needs, even small habitat fragments can provide viable habitat for many of the ecoregion's species that are key to its biodiversity. Therefore, protecting the remaining forest patches and their natural biodiversity is imperative. Currently, the ecoregion has five protected areas-of which one (Peak Wilderness) extends partially into the ecoregion from the lowland rain forests ecoregion-that cover less than 500 square kilometers (km2) (Table 3). But none have good protection measures or conservation plans in place.

|

| ||

|

Protected Area |

Area (km2) |

IUCN Category |

|

Pidurutalagala National Park |

80 |

VIII |

|

Hakgala |

20 |

I |

|

Knuckles |

217 |

IV |

|

Peak Wilderness [IM0154] |

120 |

IV |

|

Horton Plains |

20 |

II |

|

Total |

457 |

|

|

Ecoregion numbers of protected areas that overlap with additional ecoregions are listed in brackets. | ||

In addition to instituting good management in existing reserves, an attempt should be made to link the forest patches that are contiguous with the lowland and submontane forests to create more effective conservation landscapes across the altitudinal gradient. Because the major rivers originate in the mountains and radiate outward, the altitudinal connectivity will protect the watersheds and stabilize the substrate. The frequent landslides that result in loss of life and property are a manifestation of the loss of ground cover in these montane forests. Failure to act soon will result in the loss of Sri Lanka's most valuable contribution to global conservation.

Types and Severity of Threats

The primary threats are from land clearing for plantations, agriculture, and illegal logging, even within protected areas. Most of the natural habitat has already been cleared for large-scale tea plantations, but the few remaining patches are still being cleared for other agricultural crops. Mining for precious stones have devastated large areas of forests.

The cloud forests in the high montane areas, especially in the Horton Plains National Park, are experiencing diebacks. Investigations are under way to determine the causes.

In the Knuckles Range the undergrowth in large forest areas is being cleared for cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) plantations. Therefore, the regeneration capacity of these forests-though seemingly intact because of the intact canopy-is highly compromised.

Justification of Ecoregion Delineation

Sri Lanka's forests have been divided into two broad climatic sub-regions: the wet zone and the dry zone. In a previous analysis of conservation units of the Indo-Malayan realm, MacKinnon placed the wet-zone forests into a single biounit, Ceylon Wet Zone 02. We used MacKinnon's regional classification as a guiding framework in delineating ecoregions across the Indo-Pacific region. But because we differentiated between lowland and montane forests in delineating ecoregions, we used the 1,000-m contour to extract and place the montane rain forests into a distinct ecoregion: the Sri Lanka Montane Rain Forests. This ecoregion includes the montane floristic zones (9, 10, 12, 13, 14, and 15) identified by Ashton and Gunatilleke.

Additional information on this ecoregion

- For a shorter summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

- To see the species that live in this ecoregion, including images and threat levels, see the WWF Wildfinder description of this ecoregion.

- World Wildlife Fund Homepage

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |