Southeastern Iberian shrubs and woodlands

The Southeastern Iberian shrubs and woodlands ecoregion, located on the southeastern coast of Spain, is characterized by a warm and dry climate with volcanic rock forming portions of the coast. Although there is an almost complete absence of tree species, the endemism rate of the vegetation, at about forty-two percent, is extremely high. Fauna of this area is not well documented. However, the Iberian Peninsula is well known for its high diversity of avifauna. Little bustard (Tetrax tetrax), black-bellied sandgrouse (Pterocles orientalis), lesser short-toed lark (Calandrella rufescens), thekla lark (Galerida theklae), black wheatear (Oenanthe leucura), and Dupont´s lark (Chersophilus duponti) all reside here, in addition to a large population of flamingos and two endangered seagulls. The ecoregion serves as an important stop for migrating birds between Europe and Africa. It is unclear how much of an impact mining and overgrazing has had on the character of the ecoregion, however, these activities continue to threaten this area’s biodiversity along with recent growth of tourism and urbanization.

Location and General Description

The Southeastern Iberian shrubs and woodlands ecoregion covers a very small area, restricted to a narrow strip of land on the southeastern coast of Spain (Almeria and Murcia). Climatically, the ecoregion is characterized by very warm (winter average temperature of about 11 to 12º Celsius) and extremely dry (between 200 and 250 millimeters (mm) of Annual rainfall) conditions. Strong dry winds such as the Saharan "siroco" occur frequently, intensifying drought. Geologically, this ecoregion has a very complex lithological composition and relief. Volcanic rock predominates on certain [[coast]al areas] (i.e. Cabo de Gata). Cenozoic and Quaternary sedimentary rocks, mainly, marl, gypsum, limestone, sands, and conglomerates, define low plains, hills, and mountain badlands.

This ecoregion is distinguished by an almost complete absence of tree species. Some xeric conifer species appear infrequently, such as pine, juniper, and the exceptional relict population of the endemic North African conifer species Tetraclinis articulata. Tamarix spp., white poplar, and oleander trees are also found in the seasonally dry riverbeds. The ecoregion’s vegetation is formed by "open high-shrub communities", which include many North African plant species such as Ziziphus lotus, Withania frutescens, Rosmarinum eriocalyx, Maytenus senegalensis, Cistus libanotis, Ephedra fragilis, Genista ramossisima, Chamaerops humilis, and Launaea arborescens.

Many different small shrub communities and grasslands characterize the ecoregion vegetation. Halophyte communities grow on salt-rich soils. This includes several species from the genera Suaeda, Salsola, Limonium and Arthrocnemum, as well as Atriplex halimus, Anabasis articulata, and Haloxylon articulatum. Dry sub-shrub communities host a large number of aromatic and medicinal plants, including several species from the genera Thymus, Salvia, Sideritis, Teucrium, and Lavandula, and also other herbaceous and succulent species (i.e. Caralluma europaea). Dry grasslands are characterized by several macro-herbaceous species from the genus Stipa, Lygeum spartum, and subshrubs such as Artemisia herba-alba. This vegetation is very similar in physionomy and plant composition to the extensive grasslands of the North African High Plateaus.

Biodiversity Features

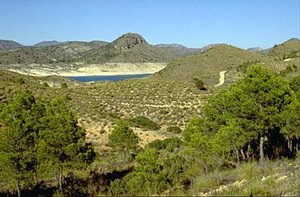

Southeastern Spain. Source: Pedro Regato / WWF MedPO)

Southeastern Spain. Source: Pedro Regato / WWF MedPO) The ecoregional flora is characterized by the presence of many Irano-Turanian and Saharo-Sindic vicarious steppe species. The endemism rate of the steppe vegetation, which mainly are species related to salt and gypsum substrates, is quite high at about 42% of the total native steppe flora of 302 species. Examples are Vella' bourgaeana, Gypsophila struthium, Salsola genistoides, Sideritis leucantha, S. Pusilla, S. Foetens, and S. Glauca.

The faunal species of this ecoregion are quite unknown. Nevertheless, it seems that only bird species are specifically adapted to the semi-arid steppe character of this ecoregion, resulting in a very rich group of species. These include little bustard (Tetrax tetrax), black-bellied sandgrouse (Pterocles orientalis), lesser short-toed lark (Calandrella rufescens), thekla lark (Galerida theklae), black wheatear (Oenanthe leucura), and Dupont´s lark (Chersophilus duponti). A number of coastal lagoons are very important areas for migratory bird species. There are more than 2000 flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) in Cabo de Gata, and the endangered seagulls, Audouin's gull (Larus audouinii) and slender-billed gull (L. Genei), as well as stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus) are found in Punta Entinas-Sabinar.

A number of mammal species should be highlighted within the ecoregion. These are red fox (Vulpes vulpes), small-spotted genet (Genetta genetta), and Eurasian badger (Meles meles).

Current Status

Coto Dorana National Park, Spain. (Photograph by WWF-Canon / Michel Gunther)

Coto Dorana National Park, Spain. (Photograph by WWF-Canon / Michel Gunther)

It is not clear how much of the semi-arid steppe-like character of the ecoregion is the result of its history of very intense human impact. In fact, scientists are currently debating the high probability that the intense erosion process that formed the ecoregional "{C}{C}badlands" was provoked by the geologic instability of the region. Faults and earthquakes as a result of an intense elastic rebound may have altered the landscape much earlier than the appearance of humans. Nevertheless, there are historical evidences of intense human pressure mainly due to overgrazing, and mining. The fuel requirement for lead mining in Sierra de Gádor from 1818 until 1880, at that time the world’s most productive lead zone, denuded most of the surrounding [[mountain]s], resulting in an intense degradation of vegetation cover, which is difficult to quantify.

Rural abandonment during the last fifty years has provoked the almost complete disappearance of traditional pastoral (sheep and goats) management and of grassland harvesting for paper pulp production.

Types and Severity of Threats

Recent land use changes, such as intense greenhouse agriculture and coastal tourism development, have produced significant impact. These are difficult to challenge due to the high economic interests behind them. Greenhousing, house building, and golf courses are threatening important habitats and the fragile water balance of the ecoregion (water-bearing salinization). Uncontrolled collection of aromatic and medicinal plants is a growing threat in the ecoregion, as referred to by TRAFFIC in the 1999 report on medicinal plants in Europe.

| Degree of Protection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Area Name & Creation Date | PA size (ha) | % Ecor. Prot. | Designation & IUCN Cat. | Major Forest Types |

| Spain | Cabo de Gata (1989) | 26.000 | Natural Park ZEPA (Special Protection Zone for Birds) | Xeric and halophyte shrublands, grasslands, riverine shrublands, coastal lagoons. | |

| Spain | Sierra Alhamilla (1989) | 8,500 | ZEPA | Xeric woodlands shrublands, and grasslands, riverine shrublands. | |

| Spain | Punta Entinas-Sabinar (1989) | 1,960 | Nature reserve | Coastal lagoon. | |

| Spain | Desierto de Tabernas (1989) | 11,625 | Natural site | Xeric and halophyte shrublands, grasslands, riverine shrublands. | |

Justification of Ecoregion Delineation

This ecoregion is equivalent to the DMEER (2000) unit of the same name. It is based on the thermo-Mediterranean xeric scrub of the southeastern Iberian peninsula.

Additional Information on this Ecoregion

- For a shorter summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

Further Reading

- Bacaria, J. et al. 1999. Environmental Atlas of the Mediterranean. Fundaciò Territori i Paisatge Eds. ISBN: 8473065921

- Bohn, U., G. Gollub, and C. Hettwer. 2000. Reduced general map of the natural vegetation of Europe. 1:10 million. Bonn-Bad Godesberg 2000.

- Casado, S. and C. Montes 1995. Guía de los Lagos y Humedales de España. Reyero Ed. Madrid. ISBN: 8460531090

- Costa, Morla and Sainz editors. 1997. Los bosques Ibéricos. Una interpretación geobotánica. Planeta Ed. ISBN: 8408019244

- Davis, S.D., V.H. Heywood and A.C. Hamilton, editors. 1994. Centres of Plant Diversity. A Guide and Strategy for their Conservation. Volume 1. Europe, Africa, South West Asia and the Middle East. IUCN Publications Unit, Cambridge, U.K. 354 pp.

- Digital Map of European Ecological Regions (DMEER), Version 2000/2005. Digital map of european ecological regions.

- Elena-Rosselló, R. 1997. Clasificación Biogeclimática de España Peninsular y Balear. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Madrid.

- Gomez Campo, C. 1985. Plant Conservation in the Mediterranean Ecosystems. Junk Ed. (Geobotanica 7).

- Heath, M.F. and Evans, M.I., editors. 2000. Important Bird Areas in Europe: Priority sites for conservation. Vol 2: Southern Europe. BirdLife International (BirdLife Conservation Series No: 8). ISBN: 0946888361

- Kunkel, G. 1987. Florula del desierto almeriense. IEA. Granada. ISBN: 8450570190

- McNeill, J.R. 1992. The Mountains of the Mediterranean World. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN: 0521522889

- Ramsar. 2000. The Annotated Ramsar List. Retrieved 2001. Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

- Regato, P., et al. 1995. Analysis of the landscape changes in the mediterranean mountain regions of Spain: seven case studies. In (Jongman Ed.) Landscape changes in Europe, ECNC, Netherlands.

- Sainz Ollero, H. and J.E. Hernández-Bermejo 1981. Síntesis corológica de las dicotiledoneas endémicas de la Pen´nsula Ibérica e Islas Baleares. INIA, Madrid.

- Suarez, F. et al. 1992). Las estepas ibéricas. MOPU, Madrid.

- Water, K.S., and Gillett, H.J., editors. 1998. 1997 IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants. Compiled by WCMC. IUCN, Publication Service Unit, Cambridge.

- WWF. 2001. The Mediterranean forests. A new conservation strategy. WWF, MedPO, Rome.

- WWF. In preparation. Mediterranean Forest Gap Analysis Database. WWF, MedPO, Rome.

- Jiménez-Caballero, S. 2000. El estado de conservaciòn y la protecciòn de los bosques españoles. Panda N. 68. WWF, España.

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |