Physical properties of water

| Topics: |

Figure 1: The atomic structure of a water (or dihydrogen monoxide) molecule consists of two hydrogen (H) atoms joined to one oxygen (O) atom. (Source: PhysicalGeography.net)

Figure 1: The atomic structure of a water (or dihydrogen monoxide) molecule consists of two hydrogen (H) atoms joined to one oxygen (O) atom. (Source: PhysicalGeography.net) We live on a planet that is dominated by water. More than 70% of the Earth's surface is covered with this simple molecule. Scientists estimate that the hydrosphere contains about 1.36 billion cubic kilometers of this substance mostly in the form of a liquid (water) that occupies topographic depressions on the Earth. The second most common form of the water molecule on our planet is ice. If all our planet's ice melted, sea level would rise by about 70 meters.

Water is also essential for life. Water is the major constituent of almost all life forms. Most animals and plants contain more than 60% water by volume. Without water, life would probably never have developed on our planet.

Water has a very simple atomic structure. This structure consists of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom (Figure 1). The nature of the atomic structure of water causes its molecules to have unique electrochemical properties. Due to the way in which the hydrogen atoms are attached to the oxygen atom, the hydrogen side of the water molecule has a slight positive charge. On the other side of the molecule a negative charge exists. This molecular polarity causes water to be a powerful solvent and is responsible for its strong surface tension.

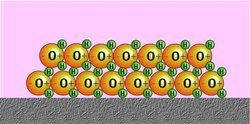

Figure 3: The following illustration shows how water molecules are attracted to each other to create high surface tension. This property can cause water to exist as an extensive thin film over solid surfaces. In the example above, the film is two layers of water molecules thick. (Source: PhysicalGeography.net)

Figure 3: The following illustration shows how water molecules are attracted to each other to create high surface tension. This property can cause water to exist as an extensive thin film over solid surfaces. In the example above, the film is two layers of water molecules thick. (Source: PhysicalGeography.net) When the water molecule makes a physical phase change its molecules arrange themselves in distinctly different patterns (Figure 2). Frozen water molecules arrange themselves in a particular highly organized rigid geometric pattern that causes the mass of water to expand and to decrease in density and volume. Expansion of the water molecule at freezing allows ice to float on top of liquid water. Figure 2 shows a slice through a mass of ice that is one molecule wide. In the liquid phase, water molecules arrange themselves into small groups of joined particles. The fact that these arrangements are small allows liquid water to move and flow. Water molecules in the form of a gas are highly charged with energy. This high energy state causes the molecules to be always moving reducing the likelihood of bonds between individual molecules from forming.

Water has several other unique physical properties. These properties are:

- Water has a high specific heat. Specific heat is the amount of energy required to change the temperature of a substance. Because water has a high specific heat, it can absorb large amounts of heat energy before it begins to get hot. It also means that water releases heat energy slowly when situations cause it to cool. Water's high specific heat allows for the moderation of the Earth's climate and helps organisms regulate their body temperature more effectively.

- Water in a pure state has a neutral pH. As a result, pure water is neither acidic nor basic. Water changes its pH when substances are dissolved in it. Rain has a naturally acidic pH of about 5.6 because it contains naturally derived carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

- Water conducts heat more easily than any liquid except mercury. This fact causes large bodies of liquid water like lakes and oceans to have essentially a uniform vertical temperature profile.

- Water molecules exist in liquid form over an important range of temperature from 0 - 100° Celsius. This range allows water molecules to exist as a liquid in most places on our planet.

- Water is a universal solvent. It is able to dissolve a large number of different chemical compounds. This feature also enables water to carry solvent nutrients in runoff, infiltration, groundwater flow, and living organisms.

- Water has a high surface tension (Figures 3 and 4). In other words, water is adhesive and elastic, and tends to aggregate in drops rather than spread out over a surface as a thin film. This phenomenon also causes water to stick to the sides of vertical structures despite gravity's downward pull. Water's high surface tension allows for the formation of water droplets and waves, allows plants to move water (and dissolved nutrients) from their roots to their leaves, and the movement of blood through tiny vessels in the bodies of some animals.

- Water molecules are the only substance on Earth that exist in all three physical states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas. Incorporated in the changes of state are massive amounts of heat exchange. This feature plays an important role in the redistribution of heat energy in the Earth's atmosphere. In terms of heat being transferred into the atmosphere, approximately three-fourths of this process is accomplished by the evaporation and condensation of water.

- The freezing of water molecules causes their mass to occupy a larger volume. When water freezes it expands rapidly adding about 9% by volume. Fresh water has a maximum density at around 4° Celsius (see Table 1). Water is the only substance on this planet where the maximum density of its mass does not occur when it becomes solidified.

| Table 1: Density of water molecules at various temperatures. | |

|---|---|

| Temperature (degrees Celsius) |

Density (grams per cubic centimeter) |

| 0 (solid) | 0.9150 |

| 0 (liquid) | 0.9999 |

| 4 | 1.0000 |

| 20 | 0.9982 |

| 40 | 0.9922 |

| 60 | 0.9832 |

| 80 | 0.9718 |

| 100 (gas) | 0.0006 |

Further Reading