Northern bottlenose whale

The Northern bottlenose whale (scientific name: Hyperoodon ampullatus) is one of 21 species of beaked whales (Hyperoodontidae or Ziphiidae), medium-sized whales with distinctive, long and narrow beaks and dorsal fins set far back on their bodies. They are marine mammals within the order of cetaceans..

Northern bottlenose whales spyhopping, Source: Hilary Moors Northern bottlenose whales spyhopping, Source: Hilary Moors

|

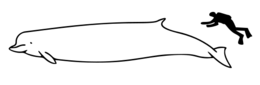

Size comparison of an average human against a Northern bottle-nosed whale. Source: Chris Huh Size comparison of an average human against a Northern bottle-nosed whale. Source: Chris Huh

|

|

Conservation Status: |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

The Northern bottlenose whale is a toothed whale (having teeth rather than baleen), up to ten metres in length. It has a dark grey to chocolate brown dorsal and lateral colouration and somewhat lighter below. Much of the face may be light grey in colour. Adults are often covered with scratches and scars. It may be confused with Cuvier's beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris) but can be recognised by having a very distinct beak and a very steep, often bulbous forehead. These features are more pronounced in older male individuals.

The specific part of the scientific name, ampullatus, means flask and refers to the bottle-like shape of the head. Young individuals are dark on the dorsal surface (back) with a light belly, and become paler as they age. In males a whitish patch develops on the forehead, which becomes larger as the male gets older. The robust body is spindle-shaped, and the dorsal fin is triangular and placed far behind centre. Northern bottlenose whales have two teeth on the lower jaw; these only erupt on males.

Northern bottlenose whales are usually found in small pods of four to ten individuals, with some degree of either age or sex segregation. It can be seen, on occasion, to leap clear out of the water. Dives may last up to two hours in length (Kinze, 2002).

This species is highly inquisitive and frequently approaches boats. This has made them more susceptible to scientific study, whale watching and hunting than the other beaked whales.

They feed on deep-water squid, as well as other invertebrates and various fish species, using sonar to detect their prey; when hunting they dive to depths of 1000 metres or more. This species is unusual as it spends the whole year in cold water, and does not make seasonal migrations like most other whales. The average life span of this whale is thought to be somewhere between 30 and 40 years.

This species prefers deep water and may avoid shallows. It has been caught in nets at depths below 1000 m. In the Arctic Ocean, the whales stay near the boundaries between cold polar currents and warmer Atlantic currents, where the food supply is rich. Squid and a variety of fish make up most of their diet.

Their growth pattern has been measured by counting annual growth rings that appear naturally in their teeth, much like tree growth rings. Males reach full size at 20 years and females, which tend to be smaller, at 15 years.

Based on geological evidence, the Northern bottlenose whale and the Southern bottlenose whale probably diverged as recently as 15,000 years ago. The northern bottlenose whale is the only species of the genus Hyperoodon that lives in the North Atlantic, but there is an unidentified species of whale living in the North Pacific that may turn out to belong to this genus.

Contents

Physical Description

Individuals of this species can reach up to 9.8 metres (m) in length, but most are around 6.7 to 7.6 m at the age of sexual maturity (7-14 years). They are sexually dimorphic, with males being up to 25% larger than females. For example the length range in adult males is typically 9.0 to 9.5 m for males; 8.0 to 8.5 m for females. Correspondingly mature males have a body mass of about 10,000 kilograms contrasting with 7500 kg for females.

The size of individuals in the Gully population (off Nova Scotia) is believed to be some 0.7 m shorter than that of other Northern bottlenose whales. Individual whales may live up to 37 years (Herman 1980, MacDonald 1987, Whitehead et al. 1997a).

Northern bottlenose whales are varied in color, ranging from greenish-brown to chocolate and gray. Individuals may be blotted with patches of grayish-white and coloration is generally lighter on the flanks and underbelly, fading to a white or cream color. Young calves are generally chocolate colored in appearance (Evans 1987, Tinker 1988).

The body is long, robust and cylindrical and the beak is short, resembling a bottle in shape. Both sexes have large, protruding melons that are often vertical anteriorly in older animals and turn yellowish-white with age in males. The melon of the female is not as prominent as that of the male.

The posteriorly-curved dorsal fin is 30-38 cm in height and is located at a distance of one third the total body length from the tail. The tail fluke lacks a medial notch and the flippers are small and pointed (Minasian et al. 1984, Tinker 1988).

The dentition of the species is highly reduced, with males possessing one or occasionally two pairs of short teeth in the tip of the lower jaw. These teeth never erupt in females, may never fully erupt in males, and often fall out with age (Minasian et al. 1984). (Herman, 1980; MacDonald, 1987; Whitehead et al., 1997a)

Other Physical Features: Endothermic; Bilateral symmetry

Behaviour

Northern bottlenose whales are generally found in groups of four to ten individuals, although group size may occasionally number as many as 25 individuals. Whalers observed that adult males sometimes travel separately from females and young males, and that this behavior occurs most commonly before and during the yearly migration. Data collected from The Gully population near Nova Scotia indicates that there may be long-term companionships between a small proportion of males and females (Harrison and Bryden 1988, Minasian et al. 1984, Reeves et al. 1993).

The Northern bottlenose whale is generally migratory, spending the spring and early summer in the more northern latitudes and migrating south for the winter, and consists of at least two distinct populations.

The larger population summers off Cape Chidley and across the mouth of the Hudson Straight to the mouth of Cumberland Sound along the 1000m depth contour and is widely distributed. The smaller population summers in a 20km x 8km area near the entrance of The Gully off the coast of Nova Scotia. Studies of The Gully population indicate that this population is likely non-migratory, remaining near Sable Island throughout the year.

Strandings of Northern bottlenose whales off the coast of Europe in early fall indicate that many Northern bottlenose whales migrate to more southernly latitudes beginning in July (Reeves et al. 1993, Whitehead et al.1997a, Whitehead et al. 1997b).

These whales emit powerful ultrasonic clicks as well as low-intensity sounds which are audible to humans. Ultrasonic sounds are amplified in the melon and may serve in the echolocation of prey, especially in deep or murky water where there is little light penetration. Unlike other beaked whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus is not prone to mass beachings (Evans 1987, MacDonald 1987, Reeves et al. 1993, Simmons and Hutchinson 1996).

Although the species surface behavior is variable, Hyperoodon ampullatus freqently approaches sluggish ships and may circle around them for an hour or more. This behavior, coupled with the tendancy for group members to aid an injured individual, made the Northern bottlenose whale a favorite target of whaling vessels (Harrison and Bryden 1988, Minasian et al. 1984, Reeves et al. 1993).

Key Behaviors: natatorial; motile; migratory; social; dominance hierarchies

Lifespan

Longevity is estimated to be at least 37 years of age, and is thought to be even greater.

Reproduction

The mating system of Northern bottlenose whales is believed to be polygynous, with a single mature male associating with a group of females during the mating season, which can be spring to early summer. Females become sexually mature at a length of 6.7-7.0 m (8-14 years) and males reach maturity at 7.3-7.6 m (seven to nine years) (Evans 1987, MacDonald 1987, Minasian et al. 1984).

Mating occurs in spring and early summer and calves are born from April to June. Calves are approximately 3.5 m in length at birth, and weaning occurs at around one year of age.Data from the Gully population near Nova Scotia indicates that the mating and calving period for this population may be from June to August. The gestation period for all Northern bottlenose whales is around twelve months and females exhibit a calving interval of two to three years. (Whitehead et al. 1997a, MacDonald 1987, Reeves et al. 1993, Tinker 1988).

Key reproductive features are: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Viviparous.

Distribution and Movements

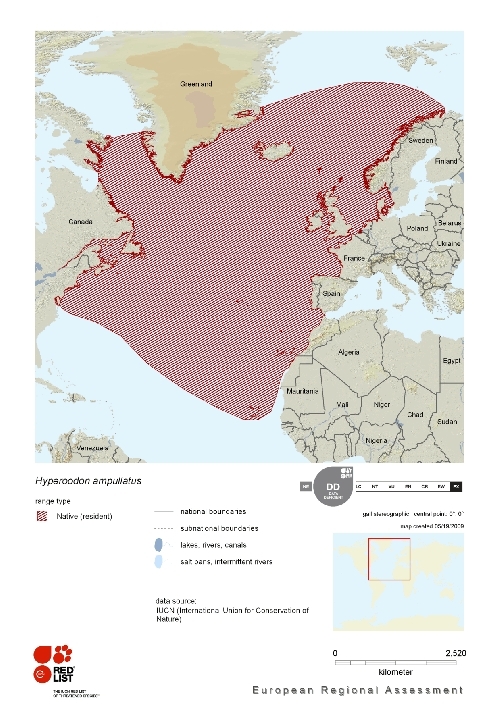

The range of Hyperoodon ampullatus (the northern bottlenose whale) extends from the polar ice of the North Atlantic southwest to Long Island Sound and southeast to the Cape Verde Islands. (MacDonald, 1987; Minasian, Balcomb, and Foster, 1984)

Habitat

Hyperoodon ampullatus is most commonly found in waters at least 1000 m deep and often forages at or near the north atlantic ice shelf in sheltered embayments during the spring and summer. (Reeves, Mitchell, and Whitehead, 1993)

Feeding Habits

Northern bottlenose whales feed primarily on squid (e.g. Gonatus fabricii), although sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea), herring (Clupea harrengus), cuttlefish (Sepiidae), sea stars (Asteroidea), and other benthic invertebrates supplement the diet; other aquatic crustaceans and certain mollusks also comprise part of the diet.

Utilizing a feeding method similar to that of Physeter macrocephalus (the Sperm whale), Northern bottlenose whales make deep, sustained dives to capture prey. Dives last up to 70 minutes, and diving depths range from 80 to 800 m with a maximum recorded dive depth of 1453 m.

Breathing intervals of 10 minutes are common between deep dives, and individuals frequently resurface in close proximity to where a dive began (Herman 1980, Hooker and Baird 1999, Minasian et al. 1984, Reeves 1993, Walker 1975).

Economic Importance for Humans

The Northern bottlenose whale was hunted for centuries for the spermaceti oil contained in its head and as a souce of food for native peoples. Scottish, English, and Norwegian whalers hunted Hyperoodon ampullatus commercially from the mid-1800's until 1973. Because of its behavior of approaching large vessels and defending injured group members, whalers found Northern bottlenose whales easy to hunt. This whale's behavior and the fact that the spermaceti oil contained in its head was of almost equal quality to that of the Sperm whale resulted in overhunting and gross reductions in Northern bottle-nosed whale populations around the turn of the century (Bloch et al. 1996, Reeves et al. 1993).

Threats and Conservation Status

The IUCN Red List reports global abundance has not been estimated, but a "rough estimate open to questions is that about 40,000 occur in the eastern North Atlantic" with another 3142 in Icelandic and 287 in Faroese waters. Further, there is a subpopulation of about 163 individuals in the Gully (Scotian Shelf). And, "fifteen years of data suggest that this population is stable." However, "most subpopulations of the species are probably still depleted, due to large kills in the past; over 65,000 animals were killed in a multinational hunt that operated in the North Atlantic from circa 1850 to the early 1970’s (Mitchell 1977; Reeves et al. 1993)." Moreover:

A study by Christensen and Ugland (1983) resulted in an estimated initial (pre-whaling) population size of about 90,000 whales, reduced to some 30,000 by 1914. The population size by the mid-1980s was said to be about 54,000, roughly 60% of the initial stock size.

Historic catch distributions indicated the existence of at least six centers of abundance, each potentially representing a separate stock (Benjaminsen 1972): i) the Gully; ii) northern Labrador-Davis Strait; iii) northern Iceland; iv) and v), off Andenes and Møre, Norway, and vi) around Svalbard, Spitzbergen. Anecdotal reports from whalers suggest a north/south seasonal migration could occur in some regions but there is little strong evidence for this and whales are reported in the Gully year round. They inhabit the most northerly waters of the Barents and Greenland seas in summer (May to August).

The main threats to the northern bottle-nosed whale are thought to be chemical and noise pollution, prey depletion, human disturbance, and hunting. This species has been hunted more than any of the other species of beaked whales. The extent to which populations of this species have been reduced by hunting is unclear, and the current status of the population is unknown.

The IUCN relieved Hyperoodon ampullatus of its "vulnerable" listing in 1991, an currently lists it as "Lower Risk, subjec to continued conservation." COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) assigned the species to its "vulnerable" category in 1996. Though not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, trade in northern bottlenose whales is restricted by CITES, the species is included in Appendix I. These whales have not been hunted commercially since 1973. (Elderkin, August 20,1998; Reeves, Mitchell, and Whitehead, 1993; Simmonds and Hutchinson, 1996) The species is classified as Data Deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List. Listed on Annex IV of the EC Habitats Directive.

All cetaceans (whales and dolphins) are listed on Annex A of EU Council Regulation 338/97; they are therefore treated by the EU as if they are included in CITES Appendix I, so that commercial trade is prohibited. This species is listed on Appendix II of the Bonn Convention and Appendix III of the Bern Convention.

United Kingdom:

In the UK. all cetaceans are fully protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 and the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order, 1985. Whaling is illegal in UK waters under the Fisheries Act of 1981. The UK recognises the authority of the International Whaling Commission concerning matters relating to regulation of whaling.

A UK Biodiversity Action Plan priority species, the Northern bottle-nosed whale is protected in UK waters by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Orders, 1985; it is illegal to intentionally kill, injure, or harass any cetacean (whale or dolphin) species in UK waters. Whaling is illegal in UK waters, and the International Whaling Commission (IWC) introduced a world moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982, which came into effect in 1986 (although Norway and Japan have continued whaling activities). Seven European countries have signed the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans in the Baltic and North Seas (ASCOBANS), including the UK. Provision is made under this agreement to set up protected areas, promote research and monitoring, pollution control and increase public awareness. Increased awareness of this species may help to secure its future.

References

- Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster, 1770). Encyclopedia of Life. Accessed 04 May 2011.

- Mundinger, G. 2000. Hyperoodon ampullatus (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 04, 2011.

- Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. 2008. Hyperoodon ampullatus. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. . Downloaded on 14 May 2011.

- IUCN Red List (November, 2008)

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Barlow, J. 1999. Trackline detection probability for long-diving whales. In: G. W. Garner, S. C. Amstrup, J. L. Laake, B. J. F. Manley, L. L. McDonald and D. G. Robertson (eds), Marine mammal survey and assessment methods, pp. 209-221. Balkema Press, Netherlands.

- Benjaminsen, T. 1972. On the biology of the bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster). Norwegian Journal of Zoology 20: 233-241.

- Bloch, D., Desportes, G., Zachariassen, M. and Christensen, I. 1996. The northern bottlenose whale in the Faroe Islands, 1584-1993. Journal of Zoology (London) 239: 123-140.

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Cañadas, A. and Sagarminaga, R. 2000. The northeastern Alboran Sea, an important breeding and feeding ground for the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) in the Mediterranean Sea. Marine Mammal Science 16(3): 513-529.

- Carwardine, M. (1995) Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Carwardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins, The Ultimate Guide to Marine Mammals. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Cetacea.org. (June, 2002)

- Christensen, I. 1975. Preliminary report on the Norwegian fishery for small whales: expansion of Norwegian whaling to Arctic and northwest Atlantic waters, and Norwegian investigations of the biology of small whales. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 32: 1083-1094.

- Council of Europe: Bern Convention (October, 2002)

- Cox, T. M., Ragen, T. J., Read, A. J., Vos, E., Baird, R. W., Balcomb, K., Barlow, J., Caldwell, J., Cranford, T., Crum, L., D'Amico, A., D'Spain, A., Fernández, J., Finneran, J., Gentry, R., Gerth, W., Gulland, F., Hildebrand, J., Houser, D., Hullar, T., Jepson, P. D., Ketten, D., Macleod, C. D., Miller, P., Moore, S., Mountain, D., Palka, D., Ponganis, P., Rommel, S., Rowles, T., Taylor, B., Tyack, P., Wartzok, D., Gisiner, R., Mead, J. and Benner, L. 2006. Understanding the impacts of anthropogenic sound on beaked whales. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 7(3): 177-187.

- Culik, B. M. 2004. Review of small cetaceans: Distribution, behaviour, migration and threats. Marine Mammal Action Plan/Regional Seas Reports and Studies 177: 343 pp.

- Dalebout, M. L. 2002. Species identity, genetic diversity, and molecular systematic relationships among the Ziphiidae (beaked whales). Thesis, University of Auckland.

- Dalebout, M. L., Ruzzante, D. E., Whitehead, H. and Oien, N. I. 2006. Nuclear and mitochondrial markers reveal distinctiveness of a small population of bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) in the western North Atlantic. Molecular Ecology 15: 3115-3129.

- Elderkin, M. August 20,1998. "Nova Scotia species at risk with official COSEWIC status" (On-line). Accessed October 13,1999

- Evans, P. 1987. Whales & Dolphins. New York, New York: Facts on File Publications.

- Forster, 1770. In Kalm, Travels into North America, 1:18.

- Gowans, S. 2002. Bottlenose whales Hyperoodon ampullatus and . In: W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig, J. G. M. Thewissen (ed.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 128-129. Academic Press, San Diego, USA.

- Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. (2011). Species.ie version 1.0 World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway (version of 15 March 2010).

- Gunnlaugsson, T. and Sigurjonsson, J. 1990. A note on the problem of false positives in the use natural marking data for abundance estimation. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 12: 143-145.

- Harrison, S., D. Bryden. 1988. Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. New York, New York: Facts on File Publications.

- Herman, L. 1980. Cetacean Behavior: Mechanisms and Functions. Malabar, Florida: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company.

- Hooker, S., R. Baird. 1999. Deep-diving behaviour of northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Cetacea: Ziphiidae). Proceedings of the Royal Society, London. B., 266: 671-676.

- Hooker, S. K., Baird, R. W., Al-Omari, S., Gowans, S. and Whitehead, H. 2001. Behavioral reactions of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus) to biopsy darting and tag attachment procedures. Fishery Bulletin 99: 303-308.

- Hooker, S. K., Whitehead, H. and Gowans, S. 1999. Marine protected area design and the spatial and temporal distribution of cetaceans in a submarine canyon. Conservation Biology 13: 592-602.

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- International Whaling Commission (October, 2002)

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Jan Haelters

- Jefferson, T. A., Leatherwood, S. and Webber, M. A. 1993. Marine Mammals of the World: FAO Species Identification Guide. United Nation Environment Programme and Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klinowska, M. 1991. Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Learmonth, J. A., Macleod, C. D., Santos, M. B., Pierce, G. J., Crick, H. Q. P. and Robinson, R. A. 2006. Potential effects of climate change on marine mammals. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 44: 431-464.

- Longevity Records: Life Spans of Mammals, Birds, Amphibians, Reptiles, and Fish (Online source)

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- MacDonald, D. 1987. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, New York: Facts on File Publications.

- Macdonald, D.W. (2001) The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Mead, J. G. 1989. Bottlenose whales Hyperoodon ampullatus,/i> (Forster, 1770) and Hyperoodon planifrons Flower, 1882. In: S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds), Handbook of marine mammals, Vol. 4: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales, pp. 321-348. Academic Press.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Minasian, S., K. Balcomb, L. Foster. 1984. The World's Whales. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

- Mitchell, E. D. 1977. Evidence that the northern bottlenose whale is depleted. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 27: 195-201.

- NBN (National Biodiversity Network), (2002). National Biodiversity Network gateway.

- North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. 1995. Report of the first meeting of the Scientific Committee. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Tromsø, Norway.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- OBIS, (2008). Ocean Biogeographic Information System. 2008-10-31

- Perrin, W. (2011). Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster, 1770). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database 2011-03-19

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Reeves, R., E. Mitchell, H. Whitehead. 1993. Status of the Northern Bottlenose Whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus. The Canadian Field-Naturalist, 107: 490-508.

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Reyes, J. C. 1991. The conservation of small cetaceans: a review.

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Ruud, J. T. 1937. Bottlenosen Hyperoodon rostratus. Norsk Hvalfangst Tidende 12: 456-458.

- Simmonds, M., J. Hutchinson. 1996. The Conservation of Whales and Dolphins. New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Steiner, L., Gordon, J. and Beer, C. J. 1998. Marine Mammals of the Azores. Abstracts of the World Marine Mammal Conference. Monaco.

- Taylor, B. L., Chivers, S. J., Larese, J. and Perrin, W. F. 2007. Generation length and percent mature estimates for IUCN assessments of Cetaceans. Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

- Tinker, W. 1988. Whales of the World. New York, New York: E.J. Brill.

- UKBAP (September, 2008)

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Vaughn, T., J. Ryan, N. Czaplewski. 2000. Mammalogy, 4th Edition. Fort Worth, Texas: Saunders College Publishing.

- Walker, E. 1975. Mammals of the World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- WDCS (June, 2002)

- Whitehead, H., A. Faucher, S. Gowans, S. McCarrey. 1997a. Status of the Northern Bottlenose Whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus, in The Gully, Nova Scotia. The Canadian Field-Naturalist, 111: 287-292.

- Whitehead, H., S. Gowans, A. Faucher, S. McCarrey. 1997b. Population Analysis of Northern Bottlenosed Whales in The Gully, Nova Scotia. Marine Mammal Science, 13: 173-185.

- Whitehead, H. and Wimmer, T. 2005. Heterogeneity and the mark-recapture assessment of the Scotian Shelf population of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 62: 2573-2585.

- Whitehead, H., Macleod, C. D. and Rodhouse, P. 2003. Differences in niche breadth among some teuthivorous mesopelagic marine mammals. Marine Mammal Science 19(2): 400-405.

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- Wimmer, T. and Whitehead, H. 2004. Movements and distribution of northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus, on the Scotian Slope and in adjacent waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology 82: 1782-1794.