Sperm whale

The Sperm whale (scientific name: Physeter macrocephalus) is a marine mammal in the order of cetaceans. It is the largest of the toothed whales (having teeth rather than baleen), with males growing up to 20 metres in length. It also has the largest brain of any living animal, and it was a sperm whale that was pitted against Captain Ahab in Herman Melville's classic novel, Moby Dick.

Sperm whale. Source: National Marine Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Sperm whale. Source: National Marine Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center

|

Size comparison of an average human against the sperm whale. Source: Chris Huh Size comparison of an average human against the sperm whale. Source: Chris Huh

|

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

Sperm whales have huge square heads, comprising almost a third of the total body length ; indeed the specific name macrocephalus means large head.

Uniquely among cetaceans, the single blowhole is located on the left of the head rather than on the top and so these whales are easily identified at a distance by their low, bushy spout, which is projected forward and slightly to the left. Further down the body toward the tail there is usually a large hump on the back, followed by a series of smaller bumps.

The dark brown to bluish-black skin, which is splotched and scratched, is said to have a texture like that of a plum stone. The inside of the mouth and the lips are white. Males tend to belarger and heavier than females, and have larger heads in relation to their body size.

The huge heads of sperm whales contain a large cavity, the spermaceti organ, filled with a waxy liquid called spermaceti oil. This wax can be cooled or heated, possibly by water sucked in through the blowhole, and thus shrinks and increases in density (helping the whale sink), or expands and decreases in density (helping the whale rise to the surface). Whalers likened the substance to semen, and this is the origin of the common name of the species.

Sperm whales are usually found in medium to large groups of up to 50 individuals, although bulls are sometimes seen alone.The tail flukes will often appear before a deep dive. Dives may last up totwo hours long (Kinze, 2002).

Sperm whales live in either nursery or bachelor groups. Nursery groups consist of a number of adult females and immature males and females. Males leave these groups when they become mature and join bachelor groups, which consist of males ofseven to 27 years of age. Older males live in small groups or singly, and visit nursery groups to mate with females during the breeding season. Most groups of sperm whales tend to number between 10 and 15 individuals.

Sperm whales use echolocation to find their prey in the dark ocean depths. When foraging, powerful sound waves are emitted from the large head; these can stun and even kill the squid, octopuses and fish on which they feed.

Males reach maturity at 10 years of age, but they do not begin to mate until they are around 19 years old and a length of 13 metres. Females become mature at betweenseven andeleven years, when they are around nine metres in length. A single calf is born between July and November after a gestation period of around 16 months. The calf is suckled for up to two years. Groups of females protect their young by adopting a defensive 'marguerite formation' in which the calves are placed in the centre of the group surrounded by a circle of females, facing tail outwards.

Sperm whales can dive deeper than 1.6 kilometres and stay under for 90 minutes, although shorter, shallower dives are more usual. They eat squid and octopus, which are sucked into the mouth whole.So large, so slow to reproduce, and once heavily hunted for their spermaceti, blubber, and ambergris, which forms in the intestines and was used in the perfume industry, sperm whales are now vulnerable. Since 1986, there has been a moratorium on hunting them.

Contents

Physical Description

Key physical features are: endothermic; homoiothermic; and bilateral symmetry. The species length ranges from 11.0-18.3 metres (m)for males and 8.3-12.5 m with females. Body mass ranges are from 11,000-57,000 kilograms (kg)for males and 6,800-24,000 kg for females. These values are applicable to mature Sperm whales.Newborn calves measure aboutfour m in lentgh, with a body mass of 700 to 900 kg.

The enormous (up toonethirdof total body length), box-like head of the Sperm whale sets it apart from all other species. This whale has the largest brain among mammals weighting about 9.2 kilograms (Ronald Nowak 1999). The blowhole slit is S-shaped and positioned forward on the left side of the head. There are 18-28 functional teeth on each side of the lower jaws, but the upper teeth are few, weak and non-functional. The lower teeth fit into sockets in the upper jaw.

The gullet of is the largest among cetaceans; it is in fact the only gullet large enough to accomodate a human.The dorsal fin is replaced by a hump and a series of longitudinal ridges on the posterior part of the back. The flippers are quite small, approximately 200 centimetres (cm) long. Tail flukes are 400 to 450 cm in width.

The blubber layer of the sperm whale is quite thick, up to 35 cm. With respect to coloration, males often become paler and sometimes piebald with age. Both sexes have white in the genital and anal regions and on the lower jaws.

Behaviour

Key species behaviors are: natatorial; motile; social; and dominance hierarchies. Giant sperm whales are very deep divers and may stay submerged from 20 minutes to over an hour. When they surface, sperm whales typically blow 20-70 times before redescending.They produce a visible spout made by the condensation of the moisture combined with a mucous foam from the sinuses. Giant sperm whales typically swim at speeds no faster than 10 kilometres (km)per hour, but when disturbed they can attain speeds of 30 km per hour.

Giant sperm whales are highly gregarious and group themselves roughly by age and sex in group sizes of 100 or more individuals. Loose family groups of about 30 individuals, however, are more common. Groups are often made up of either bachelor bulls (sexually inactive males) or nursery schools of mature females and juveniles of both sexes. Older males are usually solitary except during the breeding season.

Voice and Sound Production

Sperm whales use clicking noises for echolocation, but they also make a variety of other sounds including "groans, whistles, chirps, pings, squeaks, yelps, and wheezes" (Ellis 1980). Their voices are quite loud and can be heard many kilometers away with underwater listening devices. Each whale also emits a stereotyped, repetitive sequence of 3-40 or more clicks when it meets another whale. This sequence is known as the whale's "coda."

Lifespan

Maximum longevity in the wild has been recorded as 77 years.

Reproduction

Key reproductive features are: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); and Viviparous. Females mature sexually at 8-11 years, and males mature at approximately 10 years, although males do not mate until 25-27 years old because they do not have a high enough social status in a breeding school until that point.Gestation period is 14-16 months and a single calf is born, which nurses for up totwo years. The reproductive cycle occurs in females everytwo to fiveyears. The peak of the mating season is in the spring in both Northern and Southern Hemispheres so that most calves are born in the fall.

These whales have a polygamous mating system. During the breeding season, breeding schools composed ofone to fivelarge males and a mixed group of females and males of various ages form. At this point, there is intense competition among the males for females (including physical competition resulting in battle scars all over the heads of males). Only about 10-25% of fully adult males in a population are able to breed.

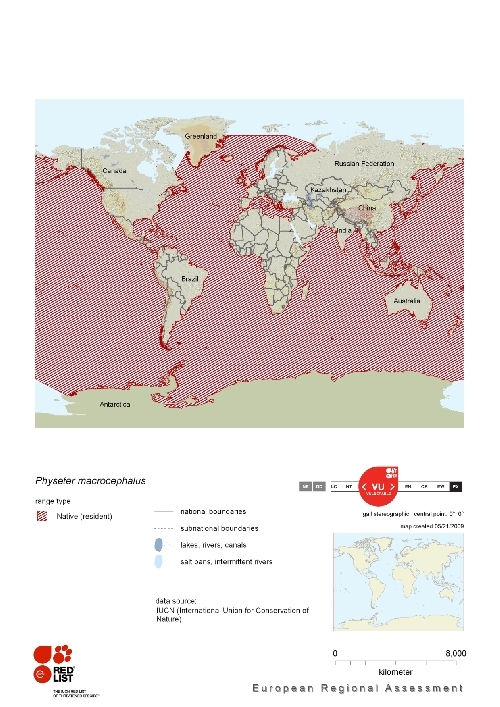

Distribution and Movements

Sperm whales are found throughout the world's oceans in deep waters to the edge of the ice at both poles (Waring et al. 2009 and references therein). According to Waring et al. (2009), results of multi-disciplinary research conducted in the Gulf of Mexico during the first decade of the 21st Century confirm speculation that Gulf of Mexico Sperm Whales constitute a stock that is distinct from other Atlantic Ocean stocks(s).

Sperm whales were commercially hunted in the Gulf of Mexico by American whalers from sailing vessels until the early 1900s. In the northern Gulf of Mexico (i.e., U.S. Gulf of Mexico), systematic aerial and ship surveys indicate that sperm whales inhabit continental slope and oceanic waters, where they are widely distributed. Seasonal aerial surveys confirm that sperm whales are present in at least the northern Gulf of Mexico in all seasons.

The best available estimates indicate a population of around 1500 Sperm whales in the northern Gulf of Mexico. (Waring et al. 2009 and references therein)

Habitat

Sperm whales swim through deep waters to depths oftwo miles, apparently limited in depth only by the time it takes to swim down and back to the surface. Their distributions are depend upon season and sexual/social status, however they are most likely to be found in waters inhabited by squid- at least 1000 metres deep and with cold-water upswellings. Because they are so well-adapted for deep water swimming, they are insignificant danger of stranding when they move inshore. This species is considered a chiefly benthic feeder and dweller.

Feeding Habits

Physeter catodon feeds mainly on squid (especially giant squid), octopus and deepwater fishes, but it also takes mollusks,sharks and skates. It consumes approximately three percent of its body mass in squid per day.

Economic Importance for Humans

The head ofeach sperm whale containsthree to fourtons of spermaceti, a substance valued as a lubricant for fine machinery and a component of automatic transmission fluid. It is also used in making ointments and fine, smokeless candles (once it solidifies into a white wax upon exposure to air). Physeter catodon has also been a target of commercial whaling in years gone by, notably in areas around the Gulf of Mexico. The meat of the whale is not generally consumed. Instead, spermaceti is extracted from the head, and the teeth are often used as a medium for the artistic form of engraving and carving known as scrimshaw. The most important product obtained from giant sperm whales is the oil once used as fuel for lamps and now used as a lubricant and as the base for skin creams and cosmetics. A gummy substance called ambergris forms in the large intestines of sperm whales and can be found floating on the surface of the water or washed ashore once it is expelled. It was once believed to have medicinal qualities, but it is now used in connection with manufacture of perfumes, based on the fact that when it is exposed to air, it hardens and acquires a sweet, earthy smell. The island Ambergris Cay, just south of the Gulf of Mexico, was given its name because of the great quantities of this substance gathered along its shores.

Being fiercely aggressive, bull giant sperm whales posed a threat to small-boat whalers in the 19th century. Sperm whales are no match for modern whaling equipment, however. They have also been known to become entangled in trans-Atlantic telephone in dives 3/4 mile deep, but this type of incident is rare.

Threats and Conservation Status

Sperm whales have a long history of commercial exploitation. Large-scale hunting began in the year 1712 in the North Atlantic, based at Nantucket in America. They were not widely hunted for their meat, but for ambergris and spermaceti. Ambergris is a substance that collects around the indigestible beaks of squid in the stomach of the whale, and was highly prized for use as a fixative in the perfume industry. Although artificial alternatives are now available, some perfume makers prefer to use ambergris today. Spermatceti was used in the production of cosmetics and candles. Sperm whales still have an economic value today for meat in Japan.

Since the 1980s, the International Whaling Commission brought an international moratorium on whaling into force. Despite this measure, Japan continues to hunt sperm whales, and relatively small numbers are taken each year with hand harpoons at Lamalera, Indonesia. Further threats include entanglement in fishing gear and collisions with boats. Although whaling has, with the exceptions outlined above, largely ceased, the after-effects of such prolonged and intensive hunting are still being felt today. It is thought that the selective hunting of the largest, breeding males will have decreased pregnancy rates, and the loss of the largest females from nursery groups would have decreased the survival of the groups.

The IUCN Red List reports that the "only recent quantitative analysis of sperm whale population trends (Whitehead 2002) suggests that a pre-whaling global population of about 1,100,000 had been reduced by about 29% by 1880 through “open-boat” whaling, and then to approximately 360,000 (67% reduction from initial) by the 1990s through modern whaling. In some areas there is concern that populations are continuing to decline."

As a species, the Sperm whale may not face immediate threat, but some populations need to be carefully monitored, and there is need for tight management of any exploitation. In the eastern tropical Pacific, recent whaling was extremely intensive, and birth rates at present are very low. The Mediterranean Sea population is particularly susceptible to collisions with ships and entanglement with fishing gear.

Sperm whales were once quite abundant in the Gulf of Mexico, but due to commercial whaling operations, they are seldom seen in this area anymore. Worldwide however, sperm whales populations are more stable than that of many other whales, although they continue to be listed as endangered by USDI (1980). The sperm whale is now the most abundant of the great whales, having been hunted with less intensity that the baleen whales. Worldwide, sperm whales number about 1,500,000.

The Sperm Whale is listed Classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List and as an endangered species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. IWC regulations have halted the commercial take of this species. Listed in CITES Appendices I and (for some countries) II. There is some concern over the number of Sperm Whales entangled in fishing gear.

References

- Katja Schulz. Editor. Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758. Encyclopedia of Life, available from "http://www.eol.org/pages/328547". Accessed 01 May 2011.

- Morvan Barnes 2008. Physeter macrocephalus. Sperm whale. Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Sub-programme [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 02/05/2011.

- Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. 2008. Physeter macrocephalus. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloadedon 28April2011.

- André, M. and Potter, J. R. 2000. Fast-ferry acoustic and direct physical impact on cetaceans: evidence, trends and potential mitigation. In: M. E. Zakharia, P. Chevret and P. Dubail (eds), Proceedings of the fifth European conference on underwater acoustics, ECUA 2000, pp. 491-496. Lyon, France.

- [Anonymous] (2009). U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments--2009. (WaringG T., JosephsonE., Maze-FoleyK., RoselP E., Ed.).NOAA Tech Memo NMFS NE 213. 528 pp..

- Bannister, J. and Mitchell, E. 1980. North Pacific sperm whale stock identity: distributional evidence from Maury and Townsend charts. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 2: 219-230.

- Barlow, J. and Cameron, G. A. 2003. Field experiments show that acoustic pingers reduce marine mammal by-catch in the California drift gill net fishery. Marine Mammal Science 19: 265-283.

- Barlow, J. and Taylor, B. L. 2005. Estimates of sperm whale abundance in the northeastern temperate Pacific from a combined acoustic and visual survey. Marine Mammal Science 21: 429-445.

- Best, P. B. 1979. Social organization in sperm whales, Physeter macrocephalus. In: H. E. Winn and B. L. Olla (eds), Behavior of marine animals, Volume 3: Cetaceans, pp. 227-289. Plenum Press.

- Best, P. B. 1983. Sperm whale stock assessments and the relevance of historical whaling records. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 5: 41-56.

- Best, P. B., Canham, P. A. S. and Macleod, N. 1984. Patterns of reproduction in sperm whales, Physeter macrocephalus. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 6: 51-79.

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Bowles, A. E., Smultea, M., Wursig, B., Demaster, D. P. and Palka, D. 1994. Relative abundance and behavior of marine mammals exposed to transmissions from the Heard Island Feasibility Test. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 96: 2469-2484.

- Branch, T. A. and Butterworth, D. S. 2001. Estimates of abundance south of 60°S for cetacean species sighted frequently on the 1978/79 to 1997/98 IWC/IDCR-SOWER sighting surveys. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 3: 251-270.

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Carwardine, M. (2000) Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Cawardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- CITES (March, 2004)

- Clapham, P. J., Berggren, P., Childerhouse, S., Friday, N. A., Kasuya, T., Kell, L., Kock, K.-H., Manzanilla-Naim, S., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Perrin, W. F., Read, A. J., Reeves, R. R., Rogan, E., Rojas-Bracho, L., Smith, T. D., Stachowitsch, M., Taylor, B. L., Thiele, D., Wade, P. R. and Brownell Jr., R. L. 2003. Whaling as science. Bioscience 53: 210-211.

- Clarke, M. R. 1977. Beaks, nets and numbers. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 38: 89-126.

- Clarke, R., Aguayo, A. and Paliza, O. 1980. Pregnancy rates of sperm whales in the southeast Pacific between 1959 and 1962 and a comparison with those from Paita, Peru, between 1975 and 1977. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 2: 151-158.

- Donoghue, M., Reeves, R. R. and Stone, G. S. 2003. Report of the Workshop on Interactions Between Cetaceans and Longline Fisheries.

- Drouot, V., Berube, M., Gannier, A., Goold, J. C., Reid, R. J. and Palsboll, P. J. 2004. A note on genetic isolation of Mediterranean sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) suggested by mitochondrial DNA. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 6: 29-32.

- Ellis, R. 1980. The Book of Whales. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Fujino, K. 1963. Identification of breeding subpopulations of the sperm whales in the waters adjacent to Japan and around Aleutian islands by means of blood typing investigations. Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries 29: 1057-1063.

- González, E. and Olivarría, C. 2002. Interactions between odontocetes and the artisan fisheries of Patagonian toothfish Disossitchus eleginoides off Chile, Eastern South Pacific. Toothed Whale/Longline Fisheries Interactions in the South Pacific Workshop.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- Gordon, J. and Moscrop, A. 1996. Underwater noise pollution and its significance for whales and dolphins. In: M. P. Simmonds and J. D. Hutchinson (eds), The conservation of whales and dolphins: science and practice, pp. 281-320. John Wiley and Sons, West Sussex, England.

- Gordon, J., Moscrop, A., Caroson, C., Ingram, S., Leaper, R., Matthews, J. and Young, K. 1998. Distribution, movements and residency of sperm whales off the Commonwealth of Dominica, Eastern Caribbean: implications for the development and regulation of the local whalewatching industry. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 48: 551-557.

- Haase, B. and Felix, F. 1994. A note on the incidental mortality of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) in Ecuador. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 15: 481-484.

- Jan Haelters

- Harrison, R. and M.M. Brayden. 1988. Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Intercontinental Publishing Corporation, New York.

- Hershkovitz, Philip. 1966. Catalog of Living Whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246. viii + 259

- Holthuis, L. B. 1987. Letters: The Scientific Name of the Sperm Whale. Marine Mammal Science, vol. 3, no. 1. 87-88

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- Husson, A. M., and L. B. Holthuis. 1974. Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758, the valid name for the sperm whale. Zoologische Mededelingen, vol. 48, no. 19. 205-217 + 3

- Hucke-Gaete, R., Moreno, C. A. and Arata, J. 2004. Operational interactions of sperm whales and killer whales with the Patagonian toothfish industrial fishery off southern Chile. CCAMLR Science 11: 127-140.

- International Whaling Commission. 1982. Report of the sub-committee on sperm whales. Report of the International Whaling Commission 32: 68-86.

- International Whaling Commission. 1994. Report of the workshop on mortality of cetaceans in passive fishing nets and traps. Report of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue) 15: 6-71.

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- IUCN Red Book, NMFS/NOAA Technical Memo

- Ivashin, M. V. and Rovnin, A. A. 1967. Some results of the Soviet whale marking in the waters of the North Pacific. Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende 56: 123-135.

- Jaquet, N., Whitehead, H. and Lewis, M. 1996. Coherence between 19th century sperm whale distributions and satellite-derived pigments in the tropical Pacific. Marine Ecology Progress Series 145: 1-10.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kasuya, T. and Brownell Jr., R. L. 2001. Illegal Japanese coastal whaling and other manipulations of catch records. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee meeting document SC/53/RMP24.

- Kasuya, T. and Miyashita, T. 1988. Distribution of sperm whale stocks in the North Pacific. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 39: 31-75.

- Keller, R.W., S. Leatherwood & S.J. Holt (1982). Indian Ocean Cetacean Survey, Seychelle Islands, April to June 1980. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 32, 503-513.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Koukouras, Athanasios. (2010). Check-list of marine species from Greece. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Assembled in the framework of the EU FP7 PESI project.

- Laist, D. W., Knowlton, A. R., Mead, J. G., Collet, A. S. and Podesta, M. 2001. Collisions between ships and whales. Marine Mammal Science 17: 35-75.

- Linnaeus, C. von. 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, ed. 10, vol. 1. 823

- Linnaeus, C., 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classis, ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1:76.Tenth Edition, Vol. 1. Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 824 pp.

- Longevity Records: Life Spans of Mammals, Birds, Amphibians, Reptiles, and Fish (Online source)

- Lowery, G.H. Jr. 1974. The Mammals of Louisiana and Its Adjacent Waters. Kingsport Press, Inc., Knoxville, TN.

- Lyrholm, T., Leimar, O., Johanneson, B. and Gyllensten, U. 1999. Sex-biased dispersal in sperm whales: contrasting mitochondrial and nuclear genetic structure of global populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 266: 347-354.

- Madsen, P. T. and Møhl, B. 2000. Sperm whales (Physeter catodon L. 1758) do not react to sounds from detonators. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 107: 668-671.

- Madsen, P. T., Mohl, B., Nielsen, B. K. and Wahlberg, M. 2002. Male sperm whale behaviour during exposures to distant seismic survey pulses. Aquatic Mammals 28: 231-240.

- Mate, B. R., Stafford, K. M. and Ljungblad, D. K. 1994. A change in sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) distribution correlated to seismic surveys in the Gulf of Mexico. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 96: 3268-3269.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Mesnick, S. L., Taylor, B. L., Nachenberg, B., Rosenberg, A., Peterson, S., Hyde, J. and Dizon, A. E. 1999. Genetic relatedness within groups and the definition of sperm whale stock boundaries from the coastal waters off California, Oregon and Washington. Southwest Fisheries Center Administrative Report LJ-99-12: 10 pp.

- Mitchell, E. 1975. Preliminary report on Nova Scotia fishery for sperm whales (Physeter catodon). Reports of the International Whaling Commission 25: 226-235.

- National Marine Fisheries Service. 1998. Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus): North Pacific stock. Stock Assessment Report. National Marine Fisheries Service.

- National Marine Fisheries Service. 2000. Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus): North Atlantic stock. Stock Assessment Report. National Marine Fisheries Service.

- NBN (National Biodiversity Network), (2002). National Biodiversity Network gateway. 2008-10-31

- Nielsen, J. B., Nielsen, F., Joergensen, P.-J. and Grandjean, P. 2000. Toxic metals and selenium in blood from pilot whales (Globecephala melas) and sperm whales (Physeter catodon). Marine Pollution Bulletin 40: 348-351.

- Nowak, R.M. and J.L Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. 4th edition. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

- Ronald Nowak (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.Olesiuk, P., Bigg, M. A. and Ellis, G. M. 1990. Life history and population dynamics of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 12: 209-243.

- Perrin, W. (2011). Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database on 2011-03-19

- OBIS, (2008). Ocean Biogeographic Information System. 2008-10-31

- O'Shea, T. J. (ed.). 1999. Environmental contaminants and marine mammals. In: J. E. Reynolds III and S. A. Rommel (eds), Biology of Marine Mammals, pp. 485-564. Smithsonian University Press.

- Pesante, G., Collet, A., Dhermain, F., Frantzis, A., Panigada, S., Podestà, M. and Zanardelli, M. 2002. Review of Collisions in the Mediterranean Sea. Proceedings of the Workshop: "Collisions between Cetaceans and Vessels: can we Find Solutions?" 40 (Special issue): 5-12. Rome, Italy.

- Poole, J. H. and Thomsen, J. B. 1989. Elephants are not beetles: implications of the ivory trade for the survival of the African elephant. Oryx 23: 188-198.

- Reeves, R. R. 2002. The origins and character of 'aboriginal subsistence' whaling: a global review. Mammal Review 32: 71-106.

- Reeves, R. R. and Notarbartolo Di Sciara, G. 2006. The status and distribution of cetaceans in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea. IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Malaga, Spain.

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Rendell, L. and Whitehead, H. 2003. Vocal clans in sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences B: 1-7.

- Rendell, L. and Whitehead, H. 2005. Spatial and temporal variation in sperm whale coda vocalizations: stable usage and local dialects. Animal Behavior 70: 191-198.

- Rendell, L., Whitehead, H. and Coakes, A. 2005. Do breeding male sperm whales show preferences among vocal clans of females? Marine Mammal Science 21: 317-323.

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Rice, D. W. 1974. Whales and whale research in the eastern North Pacific. In: W. E. Schevill (ed.), The whale problem: A status report, pp. 170-195. Harvard University Press.

- Rice, D. W. 1989. Sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus Linneaus, 1758. In: S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds), Handbook of marine mammals, Vol. 4: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales, pp. 177-234. Academic Press.

- Salas, R., Robotham, H. and Lizama, G. 1987. Investigacion del bacalao en la VIII Region de Chile. Informe tecnico. Intendencia Region Bio-Bio e Instituto de Formento Pesquero, Talcahuano.

- Schevill, William E. 1986. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and a paradigm: the name Physeter catodon Linnaeus 1758. Marine Mammal Science, vol. 2, no. 2. 153-157

- Schevill, William E. 1987. Letters: The Scientific Name of the Sperm Whale, Mr. Schevill replies. Marine Mammal Science, vol. 3, no. 1. 89-90

- Selys-Longchamps, E. de. 1839. Europaeorum Mammalium, Index Methodicus. Études de Micromammalogie: revue des musaraignes, des rats et des campagnols, suivie d'un index méthodique des mammifères d'Europe. 137-157

- Scott, T. M. and Sadove, S. S. 1997. Sperm whale, Physeter macrocephalus, sightings in the shallow shelf waters off Long Island, New York. Marine Mammal Science 13: 317-320.

- Slijper, E.J. (1938). Die Sammlung rezenter Cetacea des Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique Collection of recent Cetacea of the Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. Bull. Mus. royal d'Hist. Nat. Belg./Med. Kon. Natuurhist. Mus. Belg. 14: 1-33

- Smith, T.D. (ed.), (2008). World Whaling Database: Individual Whale Catches, North Atlantic. In: M.G Barnard & J.H Nicholls, HMAP Data Pages. 2008-03-13

- Starbuck, A. 1878. History of the American whale fishery. Castle.

- Tønnessen J. N. and Johnsen A. O. 1982. The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Vanhaelen, M.-Th. (1989). Some observations on the beach between Koksijde and Oostduinkerke during and after the warm summer of 1989 Waarnemingen van het strand tussen Koksijde en Oostduinkerke tijdens en na de warme zomer van 1989. De Strandvlo 9: 117-120

- Viale, D., Verneau, N. and Tison, Y. 1992. Stomach obstruction in a sperm whale beached on the Lavezzi islands: macropollution in the Mediterranean. Journal de Recherche Oceanographique 16: 100-102.

- Watkins, W. A., Moore, K. E. and Tyack, P. 1985. Sperm whale acoustic behaviors in the southeast Caribbean. Cetology 49: 15 pp.

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (March, 2004)

- Whitehead, H. 2002. Estimates of the current global population size and historical trajectory for sperm whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series 242: 295-304.

- Whitehead, H. 2002. Sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus. In: W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 1165-1172. Academic Press.

- Whitehead, H. 2003. Sperm Whales: Social Evolution in the Ocean. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, USA.

- Whitehead, H. and Rendell, L. 2004. Movements, habitat use and feeding success of cultural clans of South Pacific sperm whales. Journal of Animal Ecology 73: 190-196.

- Whitehead, H., Christal, J. and Dufault, S. 1997. Past and distant whaling and the rapid decline of sperm whales off the Galápagos Islands. Conservation Biology 11: 1387-1396.

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- World Wildlife Fund (March, 2004)

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376