North Atlantic Right Whale

Contents

North Atlantic right whale

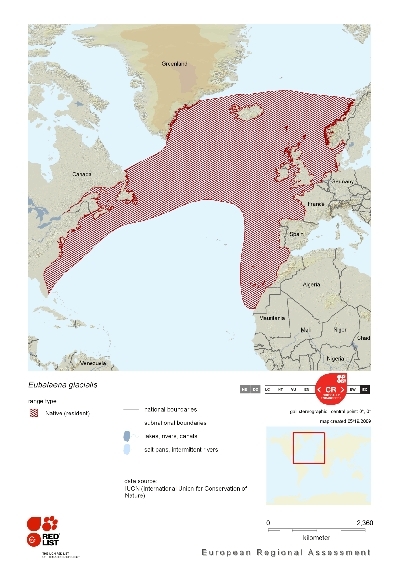

The North Atlantic right whale (scientific name: Eubalaena glacialis) is a critically endangeredmarine mammal (300 to 350 individuals estimated in 2008) in the family Balaenidae, part of the order of cetaceans. The North Atlantic right whale is a baleen whale, meaning that instead of teeth, it has long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

North Atlantic Right Whales were hunted for at least 800 years, until they became so rare that it was no longer commercially viable to exploit them. Now numbering only in the hundreds, and showing no signs of recovery, Northern right whales are nearly extinct. Some populations have not shown any significant reproduction, even after becoming protected by law.

Today, the North Atlantic right whale is a rarely seen species, but its name derives from an era when they were more frequently observed, when they swam slowly, close to shore, thus making them an easy target for whalers. Not only did this swimming behaviour make this whale the right one to hunt, but this whale also floats when dead and yielded vast quantities of valuable oil and baleen.

Despite its bulky size, the North Atlantic right whale is able to perform acrobatic acts such as jumping out of the water, known as breaching, violently slapping the water surface with the tail and/or a pectoral fin. Although the purpose of these behaviours is not fully understood, they may be used in communication. Similarly, the range of low frequency groans, moans and belches that the North Atlantic right whale makes are hypothesised to be used to communicate with other individuals, or signal aggression.

Remarkable for their large size, North Atlantic right whales feed only on minute planktonic prey, including large copepods, the size of a grain of rice; krill, a shrimp-like crustacean; tiny planktonic snails and the drifting larval stages of barnacles and other crustaceans. North Atlantic right whales are skim feeders, meaning they consume prey by swimming forward with mouths open, allowing water to flow into the mouth and out through the baleen. Tiny prey are strained from the water as it becomes caught in the fringed baleen, where it is then dislodged by the tongue and swallowed. Although this whale often feeds at or immediately below the ocean surface, the North Atlantic right whale is also believed to sometimes feed close to the bottom, since it has been seen surfacing after a 10 to 20 minute dive with mud on its head.

After feeding at northern latitudes during the summer, the North Atlantic right whale migrates south for winter. Pregnant females head for the inshore calving grounds, whilst the location of the remaining majority of the population is not known. Wherever they move, this is the season at which mating takes place.

North Atlantic right whale females typically first calve at nine to ten years of age, therafter giving birth to a single young every three years. The gestation period lasts for about one year, and following birth, the mother and her young remain close until the calf is weaned at the age of one. During its first year of life the calf learns the location of critical feeding grounds from its mother, which it will continue to visit for the remainder of its life. The female then takes a third year to replenish her energy stores before breeding again.

Northern right whales live long lives: some animals have been studied for years and one was known to be at least 67 years old when she was seen in 1992.

Physical Description

Its robust, somewhat rotund, body is mostly black, with a large head that measures up to one third of the total body length. Some individuals may also bear white patches on the underside, while others have a more mottled appearance. More often, the only conspicuous feature of this great whale is the irregular patchwork of thickened tissue, called callosites, on the rostrum (head). These callosites are inhabited by many small amphipods, known as cyamids or whale lice, and form a patternation unique to each individual whale, thus providing a means of individual identification. Callosities are prominent on the rostrum, near blowholes, near eyes, and on the chin and lower lip. These large crusty growths often harbor cyamid crustaceans, and may therefore appear white, orange, yellow or pink. Hair can be found on the tips of the chin and upper jaw and is also associated with the callosities.

The North Atlantic right whale lacks a dorsal fin, but has large, paddle-like pectoral fins used for steering, and an enormous tail that provides propulsion with powerful vertical strokes. The downward-curved mouth of the North Atlantic right whale contains between 200 and 270 baleen plates on each side of the upper jaw. These plates, each measuring around two metres long and fringed with fine hairs, replace teeth in Balaenidae whales, and are central to their method of feeding.

The North Atlantic right whale has two well partitioned blowholes situated on top of its head through which it breathes, producing a distinctive, bushy, V-shaped cloud of water spray up to five metres high when it exhales at the surface.

The largest amount of blubber found in any whales is that of the right whale group. This layer averages a thickness of 20 inches and can be as thick as 28 inches. It comprises 36 to 45 percent of the total body mass. All seven cervical vertebrae are fused into one osseous unit.

The North Atlantic right whale differs in skin colour from the North Pacific right whale and the cold waters of the Arctic Circle are a natural impediment to the mingling of these two groups.

The species length averages 17 metres (m), and may reach an extent of 18 m. Body mass of the North Atlantic right whale characteristically ranges from 60,000 to 100,000 kilograms. There is sexual dimorphism, with females generally being larger than males.

A summary of distinguishing characteristics is:

- Craggy patches on head called callosities used to identify individuals

- Lifting of large, all black tail when diving

- V-shaped, six metre high blow readily visible

- Absence of dorsal fin

- Large lower lips and narrow rostrum

- Broad throat without throat pleats

- Black to mottled grey

- White scarring or white belly patches in 30 percent of individuals.

Taxonomy

What was long treated as a single right whale species is now recognized as three distinct species by both scientists and governmental regulatory agencies. They are:

- North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis)

- North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica), which inhabits the Pacific Ocean, especially between 20o and 60o N latitude.

- Southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) occurring in the southern hemisphere between around 20o and 60o S latitude.

The Bowhead Whale is also a member of the family Balaenidae.

Behaviour

Right whales make simple and complex low-frequency noises and a belch-like utterance that is their most common vocalisation. such low-frequency sounds are chacteristic of balleen whales, while high-frequency sounds are more typical of toothed whales. Other sounds are described as grunting, mooing, moaning, sighing and bellowing. The maximum acoustic frequency recorded in Southern right whales ranges from 50 to 500 Hertz, and the duration ranges from 0.5 to 6.0 seconds. (Slijper 1979)

The North Atlantic right whale is an extremely slow swimmer, achieving an average velocity of two knots and rarely exceeding five knots. Northern right whales are migratory animals, spending the winter in warmer waters such as those found off Cape Hatteras, and migrating to the poles for cooler waters in late summer and early fall. It is rare to observe this cetacean species off the coast of Cape Cod from June to October, because they have all headed north by that season.

Right whales are not known for being gregarious, but they can be found in small groups. The typical group size ranges from a single whale to a group of 12 but usually two. The group composition varies from female-calf, all males or mixed. It is difficult to determine group size because of the group dispersion. A larger group may be formed at great distances staying in contact by acoustics. Composition of groups is rarely known because of the difficulty in sexing individuals (Evans 1987).

They are fairly social in that they will swim with other types of cetaceans. It was reported that one mother that was fed up with the playful antics of her calf swam underneath the calf, then surfaced, cradling the calf in her flippers.

Reproduction

Males are sexually mature at a length of 15.0 m and females at 15.5 m, these sizes may be reached between five and ten years of age.

Eubalaena glacialis copulates within the timeframe of December to March, the same period most of the young are born. After much nuzzling and caressing, mating right whales roll about randomly exposing flippers, flukes, backs, bellies and portions of their heads. It has been noted that the male sometimes begins precopulatory behavior by placing his chin on the exposed hindquarters of the female. It is believed that most right whales are polygamous and permanent pair bonds are not typically formed. Females likely mate with multiple males. No aggression has been observed between competing males; this absence of male aggression which is a relatively rare behaviour in mammals. Courting bouts may last for an hour or two, after which participants go their own way. Both males and females are seen on their backs at the water's surface, but females may showevince this posture to move her genitalia away from a pursuing male. Males tend to have the largest testes of any living mammal (weighing up to about 525 kg.), suggesting that sperm competition may play a significant role in determining mating success.

The overall species mating system can be characterised as polygynandrous (promiscuous). Females give birth to a single calf every three to four years. Right whales are 4.5 to 6.0 metres in length at birth. They grow rapidly thereafter, attaining a size of 12 metres by 18 months old. The length of lactation and dependence are not well known.

Lifespan/Longevity

Reliable data on mean longevity are not yet available. An indication that potential longevity can be very high was obtained by serendipity. A picture was taken of a female and her calf in 1935 in Florida. The same individual was seen in 1959 off Cape Cod and irregularly until the summer of 1995. Assuming it was her first calf in the original picture and she was at the age of sexual maturity or eight years old, she would have been approximately 67 years old when last seen.

Their close relatives, Bowhead whales, have been recorded with lifespans approaching 200 years, so it is probable that right whales have very long lifespans.

Distribution and Movement

North Atlantic Right Whales (Eubalaena glacialis) inhabit the Atlantic Ocean, especially between 20o and 60o N latitude. Most individuals in the western North Atlantic population range from wintering and calving areas in [[coast]al] waters of the southeastern USA, to summer feeding and nursery grounds in New England waters and north to the Bay of Fundy and Scotian Shelf.

In 1991, five high use areas were identified by the U.S.National Marine Fisheries Service:

- Coastal Florida and Georgia;

- Great South Channel;

- Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay;

- Bay of Fundy; and,

- Scotian Shelf

The eastern North Atlantic population may originally have migrated along the coast from northern Europe to the northwest coast of Africa. Historical records suggest these animals were heavily exploited by whalers from the Bay of Biscay (off southern Europe) and Cintra Bay (off the northwestern coast of Africa), as well as off coastal Iceland and the British Isles. During the early to mid 1900s, right whales were intensely harvested in the Shetlands, Hebrides and Ireland. Recent surveys suggest right whales no longer frequent Cintra Bay or northern European waters. Due to a lack of sightings, current distribution and migration patterns of the eastern North Atlantic right whale population are largely unknown

Habitat

Depending on the season of year and which hemisphere they're found, right whales will spend much of their time near bays and peninsulas and in shallow, coastal waters. This habitat selection can provide shelter, food abundance, and security for females rearing young or avoiding the mating efforts of males. Four critical habitats for northern right whales are the Browns-Baccaro Bank, Bay of Fundy, Great South Channel, and the Cape Cod Bay. Each of these is distinguished by high densities of copepod populations. The first three have deep basins (150 m) flanked by relatively shallow water. Copepods are concentrated in such locales because of convergences and upwellings driven by tidal currents. This phenomenon also occurs in the Cape Cod Bay even though a deep basin isn't present.

Feeding

Northern right whales tend to skim near the surface of the water feeding on small copepods, krill, and euphausiids. The whales swim along the surface, or just below, with their mouth open, skimming the zooplankton from the water. The water passes through a series of large baleen plates which filter out the food. The whale will skim the surface for a while, then close its mouth and push its tongue against the baleen to collect its meal. Whales tend not to feed until they find large concentrations of food. When they find these concentrations, they swim through the mass, making accurate adjustments to their course in order to maximize their intake (Slijper 1979, Evans 1987).

Predation

Although North Atlantic Right Whales typically do not live together in groups, they may temporarily cluster together to form a defensive circle when threatened by a potential predator. In those circumstances, the whales form a circle with flailing tails pointed outwards. They may also move into shallow waters to attempt to avert the predator, but sharks and killer whales (orcas) are able to continue to stalk in these depths. The right whale was hunted by man easily, because this cetacean comes close to shore, is slow-moving and floats when killed (Evans 1987).

These whales are protected from most predators by their formidable size, although calves may be targeted by killer whales (orcas) and sharks.

Hunting of the North Atlantic right whale

The IUCN reports:

The first records of Basque whaling in the Bay of Biscay are from the 11th century. At least dozens of whales were taken each year in the Bay of Biscay until a marked decline was evident by 1650, and whaling declined during the 18th century.

Basque whalers arrived in Iceland as early as 1412, and participated in the right whale fishery around the British Isles and Norway from the 14th to the 18th century, but probably many more whales were taken by Dutch, Danish, British and Norwegian whalers.

Quantitative estimates of catches are not available. Historic right whale catches as far north as Iceland and Norway appear to have been mainly E. glacialis, with Balaena mysticetus (bowhead) being the main species only in the far north (Greenland and Svalbard) (Aguilar 1986).

Smith et al. (2006) documented extensive whaling for E. glacialis in the North Cape area (northern Norway) in the 17th century.

Right whaling in the northeastern Atlantic seems to have declined from the mid-17th century and all but disappeared by the mid-18th century, but there was a brief period of right whale catches by modern whalers operating from shore stations in the British Isles and off Iceland, with at least 120 right whales were taken during 1881-1924 (Collett 1909, Brown 1986).

The last recorded catch was a cow-calf pair off Madeira in 1967, accompanied by a third individual that escaped.

It is not clear when Basque whaling began in the northwestern North Atlantic, but it had been established no later than 1530. It has long been thought that large numbers (tens of thousands) of right whales were taken off Labrador and Newfoundland by the Basques between 1530 and 1610 (Aguilar 1986, Reeves 2001) but recent genetic evidence suggest that many if not most of these were bowheads (Rastogi et al. 2004).

Shore-based whaling along the US east coast began in the mid 17th century and continued at least sporadically over the next two and a half centuries (Reeves et al. 1999, IWC 2001a). Reeves et al. (2007) estimated as a lower bound that some 5,500 right whales (and “possibly twice that number”) were removed by whaling in the western North Atlantic between 1634-1951.

Conservation

Northern Atlantic right whales are the most critically endangered great whale.

Years of whaling, starting in the 11th century and becoming a modern industrial practice in the early 20th century, have left North Atlantic right whale stocks seriously depleted in the western Atlantic, and virtually extinct in the eastern Atlantic. They were killed in their thousands for their valuable oil and baleen, until commercial whaling was prohibited by the International Whaling Commission in 1935. Whilst the North Atlantic right whale is no longer hunted, decades of exploitation have left a tragic legacy. The small, remaining population, concentrated along the heavily industrialised coast of north-eastern America, is highly vulnerable to the impacts of human activities.

As of 2008, there are a scant 300 and 350 North Atlantic right whales remaining, the species survival thus rests in an extremely precarious situation.

The ESA and IUCN both list the Northern Right Whale as an [[endangered]species]. Most commercial exploitation of this species was halted by the 1920s, and the taxon is now protected in more than 120 countries. Entanglement and ship-strikes are ongoing major concerns. Unfortunately, the population is showing little sign of recovering.

Collision with ships is currently the most serious source of mortality threatening the North Atlantic right whale, and was the cause of 16 known North Atlantic right whale deaths between 1970 and 1999. This is closely followed by the threat of entanglement in commercial fishing gear, either active gear or nets that have been lost or damaged. Known as ghost gear, this fishing equipment continues to wreak havoc on marine species, with three North Atlantic right whales known to have died from entanglement since 1970 and a further eight known to have been seriously injured, most likely with fatal consequences. These numbers may sound small, but in a population of just 300 or so individuals, the consequences can be enormous.

A number of other threats may also be impacting this imperilled species, including a loss of habitat due to human activity, oil spills, man-made noise which may interfere with communication, intensive commercial fishing having secondary effects on prey availability. As the North Atlantic right whale has a relatively narrow range of prey on which it can feed, and relies on a specific combination of water currents and temperatures to create suitable feeding grounds, changes to ocean temperatures and currents caused by global climate change could have significant affects. Indeed, climate change may be the final factor that pushes this species over the brink to extinction.

A major issue revolving around the conservation of the right whale is habitat modification. Especially since the species uses shallow coastal lagoons and bays for breeding.

The history of research and conservation of northern right whales provides a number of lessons that may be applicable to other endangered species. First, sufficient funding must be provided to carry out an effective management program. Second, persistence and patience is needed to develop and implement an effective research program. Third, studies may not meet traditional scientific standards of proof because population sample sizes are necessarily small. Fourth, effective conservation will require cooperation from federal and state agencies as well as nongovernmental groups. Fifth, incidental take of a species is much harder to regulate than directed take like hunting. Lastly, humans should never become complacent about the state of our knowledge (Katona 1999).

Since the North Atlantic right whale was protected from hunting in 1935 by the International Whaling Commission (IWC), and also protected in Canada, which is not a member of the IWC, the most important conservation need for this species is the reduction, or elimination, of deaths and injuries from ship collisions and entanglement in fishing gear. Both the USA and Canada have developed recovery plans for this species, with the aim of addressing these issues, and a number of measures have already been implemented. These include regulations in the USA to restrict the use of certain types of fishing gear in areas and times where North Atlantic right whales are common, as well as regulations that specify the distance with which a whale-watching vessel or other ship may approach a North Atlantic right whale.

Since 1999, a scheme has been in place in two locales for calving and summering grounds to warn vessels when there are right whales in the vicinity; moreover, in the Bay of Fundy, shipping lanes have been moved to divert them away from the major summer concentrations of right whales. As of yet, there is no data to indicate whether such measures have been successful, and recovery of this species continues to be problematic, if not absent. If these measures have not been sufficient, the outlook for the North Atlantic right whale is grim. As it is a long lived species, extinction may not occur in the near future, but the extinction of this great whale in the next century is a very real possibility.

Further Reading

- Eubalaena glacialis (Müller, 1776) North Atlantic right whale, Encyclopedia of Life, accessed 2-10-2011

- Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. 2008. Eubalaena glacialis. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4..

- Crane, J. and R. Scott. 2002. "Eubalaena glacialis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 30, 2011 .

- Aguilar, A. 1981. The black right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, in the Cantabrian Sea. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 31: 457-459.

- Aguilar, A. 1986. A review of old Basque whaling and its effect on the right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) of the North Atlantic. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 10: 191-199.

- Anonymous. 2006. The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium 2006 Report Card.

- Baillie, J. and Groombridge, B. (comps and eds). 1996. 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Bonner, N. (1989) Whales of the world. pp. 48-58.

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Burnie, D. (2001) Animal. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Brown, S. G. 1986. Twentieth-century records of right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 10: 121-127.

- Caswell, H., Fujiwara, M. and Brault, S. 1999. Declining survival probability threatens the North Atlantic right whale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96: 3308-3313.

- Chapman, J.A., Feldhamer, G.A., (1982) Wild Mammals of north america. pp. 415-30.

- CITES (November, 2008)

- Clapham, P. J. 2003. Report of the working group on survival estimation for North Atlantic right whales. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Clapham, P. J. 2005. Update on North Atlantic right whale research and management. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Collett, R. 1909. A few notes on the whale Balaena glacialis and its capture in recent years in the North Atlantic by Norwegian whalers. Zoological Society of London: 91-98.

- Cummings, W. 1985. Right Whales. New York, N.Y.: Academic Press.

- Ellis, R. 1985. The Book of Whales. New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc..

- Evans, P. 1987. The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. New York, N.Y.: Facts on File Publications

- Fautin D, Dalton P, Incze LS, Leong J-AC, Pautzke C, et al. 2010. An Overview of Marine Biodiversity in United States Waters. PLoS ONE 5(8): e11914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011914

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Gaines, C. A., Hare M. P., Beck S. E., & Rosenbaum H. C. (2005). Nuclear markers confirm taxonomic status and relationships among highly endangered and closely related right whale species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 272, 533-542.

- Greene, C. H., Pershing, A. J., Kenney, R. D. and Jossi, J. W. 2003. Impact of climate variability on the recovery of endangered North Atlantic right whales. Oceanography 16: 98-103.

- Hamilton et al. (1998) Age structure and longevity in North Atlantic right whales Eubalaena glacialis and their relation to reproduction. Mar Ecol Prog Ser, 171:285-292.

- Hershkovitz, Philip. 1966. Catalog of Living Whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246. viii + 259

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- International Whaling Commission. 2001. Report of the subcommittee on the comprehensive assessment of whale stocks – other stocks. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 3: 209-228.

- International Whaling Commission. 2001. Report of the workshop on the comprehensive assessment of right whales: a worldwide comparison. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 2: 1-60.

- International Whaling Commission. 2001. Report of the workshop status and trends of western North Atlantic right whales. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 2: 61-87.

- International Whaling Commission. 2004. Classification of the order Cetacea. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 6(1): xi-xii.

- International Whaling Commission. 2005. Report of the subcommittee on bowhead, right and gray whales. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 7: 189-209.

- International Whaling Commission. 2006. Report of the Scientific Committee. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 8: 49.

- Jacobsen, K. O., Marx, M. K. and Oien, N. 2004. Two-way trans-Atlantic migration of a North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). Marine Mammal Science 20(1): 161-166.

- Jan Haelters

- Katona, S., S. Kraus. 1999. Efforts to Conserve the North Atlantic Right Whale. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Keller, R.W., S. Leatherwood & S.J. Holt (1982). Indian Ocean Cetacean Survey, Seychelle Islands, April to June 1980. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 32, 503-513.

- Kenney, R.D. (2002) North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Right Whales. In: Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, London.

- Knowlton, A. R. and Kraus, S. D. 2001. Mortality and serious injury of northern right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 2: 193-208.

- Kraus, S. D. and Rolland, R. M. (eds). 2007. The Urban Whale: North Atlantic Right Whales at the Crossroads. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, UK and Massachusetts, USA.

- Kraus, S. D., Hamilton, P. K., Kenney, R. D., Knowlton, A. R. and Slay, C. K. 2001. Reproductive parameters of the North Atlantic right whale. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management Special Issue 2: 231-236.

- Leatherwood, S. and R. R. Reeves. 1983. The Sierra Club Handbook of Whales and Dolphins. Sierra Club Press, San Francisco.

- Linnaeus, C., 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classis, ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tenth Edition, Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 1:75, 824 pp.

- Macdonald, D.W. (2006) The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Mayo, C.A., Marx, M.K. (1990) Surface foraging behavior of the North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, and associated zooplankton characteristics. Canadian Journal of Zoology, (68), pp. 2214-20.

- Martin, A. R. and Walker, F. J. 1997. Sighting of a right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) with calf off S. W. Portugal. Marine Mammal Science 13(1): 139-141.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Murison, L.D., Gaskin, D.E. (1989) The distribution of right whales and zooplankton in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology, (67), pp. 1411- 20.

- National Marine Fisheries Service. (2005) Recovery Plan for the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, Maryland.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Notarbartolo Di Sciara, G., Politi, E. and Bayed, A. 1998. A winter cetacean survey off southern Morocco, with a special emphasis on right whales. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 48: 547-550.

- Payne, R. (1994) Among whales. Natural History, (1), pp. 40-47.

- Perrin, W. (2010). Eubalaena glacialis (Müller, 1776). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=159023 on 2011-02-05

- Perry, S. L., Demaster, D. P. and Silber, G. K. 1999. The great whales: history and status of six species listed as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973. Marine Fisheries Review 61(1): 1-74.

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Rastogi, T., Brown, M. W., Mcleod, B. A., Frasier, T. R., Grenier, R., Cumbaa, S. L., Nadarajah, J. and White, B. N. 2004. Genetic analysis of 16th-century whale bones prompts a revision of the impact of Basque whaling on right and bowhead whales in the western North Atlantic. Canadian Journal of Zoology 82: 1647-1654.

- Reeves, R. R. 2001. Overview of catch history, historic abundance and distribution of right whales in the western North Atlantic and in Cintra Bay, West Africa. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 2: 187-191.

- Reeves, R. R., Brewick, J. M. and Mitchell, E. D. 1999. History of whaling and estimated kill of right whales, Balaena glacialis, in the northeastern United States, 1620-1924. Marine Fisheries Review 61(3): 1-36.

- Reeves, R. R., Rolland, R. and Clapham, P. J. 2001. Causes of reproductive failure in North Atlantic right whales: new avenues of research. Northeast Fisheries Science Center Reference Document 01-16.

- Reeves, R. R., Smith, T. D. and Josephson, E. A. 2007. Near-annihilation of a species: right whaling in the North Atlantic. In: S. D. Kraus and R. M. Rolland (eds), The Urban Whale: North Atlantic Right Whales at the Crossroads, pp. 39-74. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Reeves, R.R. (1979) Right whale: Protected but still in trouble. National Parks and Conservation Magazine, (2), pp. 10-15.

- Reeves, R.R., Kraus, S., Turnbull, P. (1983) Right whale refuge? Natural History, (4), pp. 40-44.

- Reeves, R.R., Smith, B.D., Crespo, E.A. and Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. (2003) Dolphins, Whales and Porpoises: 2002–2010 Conservation Action Plan for the World's Cetaceans. IUCN/SSC Cetacean Specialist Group, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Rice, D. W. 1998. Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- Rolland, R. M., Hamilton, P. K., Marx, M. K., Pettis, H. M., Angell, C. M. and Moore, M. J. 2007. External perspectives on right whale health. In: S. D. Kraus and R. M. Rolland (eds), The Urban Whale: North Atlantic Right Whales at the Crossroads, pp. 273-309. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Rosenbaum, H., R. Brownell, M. Brown, C. Schaeff, V. Portway, B. White, S. Malik, L. Pastene, N. Patenaude, C. Baker, M. Goto, P. Best, P. Clapham, P. Hamilton, M. Moore, R. Payne, V. Rowntree, C. Tynan, J. Bannister, R. DeSalle. 2000. World-wide genetic differentiation of Eubalaena: questioning the number of right whale species.. Molecular Ecology, 9: 1793-1802. Accessed December 01, 2003.

- Simmonds, M.P. and Isaac, S.J. (2007) The impacts of climate change on marine mammals: early signs of significant problems. Oryx, 41 (1): 19 - 26.

- Slijper, E. 1979. Whales. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- The Podcast of Life:Podcastium vitae is brought to you by the Encyclopedia of Life, hosted by Ari Daniel Shapiro and produced by Atlantic Public Media

- Smith, T. D., Barthelmess, K. and Reeves, R. R. 2006. Using historical records to relocate a long-forgotten summer feeding ground of North Atlantic right whales. Marine Mammal Science 22(3): 723-734.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750