Kinabalu National Park, Malaysia

Kinabalu National Park is a World Heritage Site in Eastern Malaysia located between 6º 00’ 25’’ – 6º 29’48’’N and 116º 21’30’’ – 116º 45’ 00’’E; this protected area is located entirely within the Malaysian state of Sabah on the island of Borneo. Kinabalu National Park is biogeographically an ecological island, which is home to a vast array of limited range and endemic species.

Contents

- 1 Geographical Location

- 2 Date and History of Establishment

- 3 Area

- 4 Land Tenure

- 5 Altitude

- 6 Physical Features

- 7 Climate

- 8 Vegetation

- 9 Fauna

- 10 Cultural Heritage

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 IUCN Management Category

- 17 Further Reading

- 18 See Also

Geographical Location

This World Heritage Site is located in the State of Sabah, Malaysia, in the northern part of Borneo. It is 83 kilometres (km) to the west of Kota Kinabalu, the capital of Sabah. The park boundary is determined by the co-ordinates 6º 00’ 25’’ – 6º 29’48’’N and 116º 21’30’’ – 116º 45’ 00’’E.

Date and History of Establishment

Kinabalu Park was established in 1964, following the passing of the Sabah National Parks Ordinance in 1962. Mount Kinabalu and its surrounding area became a park as a consequence of the infamous "Sandakan-Ranu Death March". In September 1944 the Japanese moved 2400 Australian and British prisoners of war from Sandakan to Ranau, a distance of 240 km. Only six prisoners survived. One of the survivors profoundly affected by the experience, Major Carter, formed the Kinabalu Memorial Committee, with the aim of preserving Kinabalu as a monument for the decency of man and a facility for the enjoyment of all of Sabah. Following two expeditions to explore the mountain and its flora by Professor John Corner, on behalf of the Royal Society of London, the idea of preserving the area was further reinforced. Corner wrote a report in 1961 entitled "The Proposed National Park of Kinabalu" and submitted it to the Governor of the Crown Colony. In 1964 the park extended over an area of 711 square kilometres (km2), this has subsequently increased in recent years.

Area

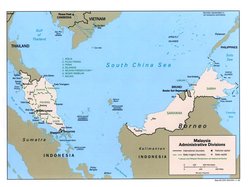

Map of Sabah, Malaysia, in northern Borneo

Map of Sabah, Malaysia, in northern Borneo

Source: University of Texas at Austin

Kinabalu National Park extends over an area of 75,370 hectares (ha) (753 km2).

Land Tenure

The park is a State owned property, managed and administered by the Board of Trustees of the Sabah Parks, a statutory body under the Ministry of Tourism Development, Environment, Science and Technology. The State government have jurisdiction over the area.

Altitude

Topography in this national park ranges from 152 metres (m) to 4095 m at Low’s Peak (the summit of Mt. Kinabalu, Malaysia’s highest peak).

Physical Features

Graves of the POWs who died in the Sandakan-Ranau Death March. (Source: Commonwealth of Australia Department of Veteran Affairs)

Graves of the POWs who died in the Sandakan-Ranau Death March. (Source: Commonwealth of Australia Department of Veteran Affairs) The park comprises of three main [[mountain]s], from south to north, Kinabalu (4095 m), Tambuyukon (2579 m) and Templer (1133 m). Six major topographical features occur with the park. These include peaks and plateau, gullies, rivers, streams and waterfalls, hot springs, caves (Paka Caves and the tumbled bats cave at Poring) and granitic slabs a characteristic of the slopes of the summit. Principle peaks include the summit peak, South peak, St. John’s Peak, Ugly Sister Peaks and No name peak. A 3.2 km spur runs in a northeastern direction from the eastern end of the summit of Mt. Kinabalu. This culminates in a long, narrow, jagged ridge at approximately 3500 m. The spur encloses a deep cleft known as Low’s Gully, which has almost vertical walls between 1000 to 1500 m. Examples of rivers flowing through the park include the Liwagu, Ulu sg. Mesilau, Sg. Kolopis, Sg. Kiibutan and the Silau-Silau stream. Some of the principal waterfalls include the Cascade Waterfalls and Liwagu Falls.

The physiogeography of Mount Kinabalu is the result of volcanic, tectonic and geological processes that occurred 1.5 million years ago. Mt. Kinabalu itself is a plutonic intrusion surrounded by metamorphosed and Tertiary sedimentary rocks. Rapid uplift followed by glacial erosion during the Ice Age accompanied by further geological activities has sculpted the mountain into its present form. The summit area of the mountain (above 3200 m) displays the effects of glacial activity in the shape of "nunataks" jagged peaks (such as Low’s Peak and South Peak), other areas shows signs of striations, grooves and polished surfaces, as well as the creation of cirques and deposit of glacial moraines. U-shaped valleys and gullies are present in the park, as well as roch moutonnés. Ultrabasic intrusive, granite and sedimentary rocks are present, acting as parent material for eight soil associations.

Climate

The nominated site has a humid tropical climate typical of the region, with temperature, humidity and rainfall varying, with altitude. February to May are generally the driest months, while October to January are the wettest. At park headquarters (1560 metres above sea level) the mean monthly temperature is approximately 20 degrees Celsius (ºC), with a daily fluctuations of 7 to 9 ºC. Mean annual rainfall at this location is 2380 millimeters (mm). A common climatic feature to the park are bright early mornings, followed quickly by clouding mid-morning, which obscures the mountains by mid-day. Showers usually occur on the upper slopes in the afternoon. In some years there are periods of prolonged dry spells, relating to the occurrence of the El Niño Southern Oscillation. This has severe effects on the park’s vegetation.

Vegetation

The nominated site contains six vegetation zones, classified according to latitude, and dominated by tropical forest. These include Lower Mountain Forest (1,200-1,900 m), Upper Montane Forest (1900 to 2700 m), Ultrabasic Rock Forest (2700 to 3000 m), Lower Granite Boulder Forest (3000 to 3300 m), Upper Granite Boulder Forest (3000 to 3800 m) and Summit or Subalpine (3200 to 4095 m).

Vegetation within the park has been further classified by Kitayama, who lists 18 types of natural vegetation, and three types of substituted vegetation. Identified vegetation communities are: tropical lowland rain forest and tropical montane rain forest, tropical subalpine coniferous forest, ecotone communities, tropical alpine ericaceous thicket, tropical alpine dwarf-shrub heath, plant communities in rocky desert, leptophyllous closed forest, leptophyllous shrubland, matted dwarf-shrubthicket, microphyllous closed forest, lepto-nanphyllous thicket, leptphyllous thicket, graminoids, plant communities on cliff, secondary closed forest, evergreen suffruticose thicket and natural bareland or moss flush. Substituted vegetation are secondary forest, weed and artificial bareland.

Tropical lowland rain forest and tropical montane rain forest are the dominant forest types, and are found between Mount Kilabalu and Mount Tambuyukon. Secondary forest that was selectively logged prior to National Park designation occurs around Mount Templer. Lowland rain forests are dominated by Dipterocarps, such as Shorea spp and Sapidaceae spp.

Mt. Kinabalu is believed to contain one of the richest and most diverse assemblages of plants in the world. A recent study by Beaman & Beaman discloses that Kinabalu flora contains as many as 5000 to 6000 species, comprising of over 200 families and 1000 genera. The park contains a high number of endemic flora. More than half (78 species) of the 135 species of Ficus occurring in Borneo can be found at the site.

Within Kinabalu National Park there are thought to be 1000 orchid species, including at least five species of slipper orchid, of the genus Papiopedillium. Papiopedillium dayanum and P. rothschildianum are considered Endangered. Other important plants occurring in the park include 608 fern species, 9 Nepenthes species (pitcher plants, including four species that are endemic to Kinabalu: Nepenthes burbidgeae, N.rajah and N. villosa), 24 Rhododendron species (five species are endemic to Kinabalu), 78 Fiscus species (over 50% of all the species found in Borneo), 52 palm species, 6 bamboo species and 30 ginger species.

Rafflesia is one of the rarest plants in the world, and is only found in very few locations in Borneo. A parasitic plant that grows from the trailing stems of wild grape-vines Tetrastigma spp. There are three species of Rafflesia in Borneo, Rafflesia Keithii is known to occur in the nominated site.

The inventory of the plants of Mount Kinabalu is ongoing. To date three volumes have been published covering ferns and fern allies, orchids and gymnosperms and non-orchid monocotyledon. Two volumes relating to dicotyledons, are due to be published shortly.

Fauna

Gibbon primate. (Source: University of Missouri-Columbia)

Gibbon primate. (Source: University of Missouri-Columbia) Kinabalu Park manifests a rich fauna that has been studied extensively. Two broad categories of mammal species are found in Kinabalu Park, lowland species and montane species. Approximately 90 species of lowland mammals have been recorded and 22 montane species of mammals. Notable among these categories are Tarsier Tarsius bancanus, Malay Bear Helarctis malayanus, Orangutan Pongo pygmaeus, Borneo gibbon Hylobates molloch, Grey-leaf monkey Presbytis aygula and Red-leaf monkey P. rubicunda and the Bay Cat Catopuma badia, Kinabalu Ferret-badger Melogale everetti.

Frog and toad species number approximately 61, while approximately 200 species of butterfly have been recorded, most of which occur below 2000 m on Kinabalu. About 112 ‘macro’ moth species have been identified, these may be found at 2000 m and above. Forty species of fish, representing nine families have been recorded. The most common are the Gastromyazontidae, that may frequently be found grazing on the surface of rocks and gravels in many of the clear mountain streams in the park.

Three hundred and twenty-six species of birds have been recorded, these may be categorized into 4 groups subalpine zone species; endemic montane species; non-endemic montane species and lowland species. Endemic Bornean species such as the Kinabalu Friendly Warbler are only found at Mt. Kinabalu and Mt. Trus Madi.

Cultural Heritage

Mt. Kinabalu has long been regarded as a sacred mountain by the native Dusun people of the foothills region.

Local Human Population

A family of 12 people occupies a 40 ha area inside the park, this family has inhabited the area for five generations. They partake in low level subsistence agriculture such as the growing of fruit trees and rice padi, as well as the collection of forest products such as bamboo, rattan and pandanus for making handicrafts.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The total number of visitors to Kinabalu Park in 1998 was 331,682. Visitor facilities are available at three locations in the Park: Park Headquarters on the southern boundary, Poring Hot Springs on the eastern boundary and at the newly established Mesilau Nature Resort also on the southern park boundary. A variety of overnight accommodation for a total of 491people is available here, as well as on Mt. Kinabalu itself. These facilities range from lodges and chalets, through to dormitory style accommodation. Other visitor amenities located at the three focal points include restaurants, gift shops, an exhibition center, an amphitheater and facilities for slide shows and interpretation. A network of trails and a canopy walkways have also been developed. Additionally, two ranger stations are located at Sayap and Sorinsim on the western and eastern boundary, for law enforcement purposes.

Scientific Research and Facilities

As the first biological reserve established in Sabah, Kinabalu Park has been studied extensively by many scientists from around the world. Particular attention has focused on the park’s flora and fauna, some of the best known of any tropical area of comparable size. The first scientific expedition to the area was by Staph in 1894, he and Gibbs compiled the first major accounts on flora. Today, over 300 research projects have been carried out in the park.

Since May 1995 four fully automated weather stations have been established at Poring Hot springs (550 m), Park Headquarters (1560 m), Carson Camp Helipad (2650 m) and Laban Rata (3270 m).

Research and education development has increased in the park since 1980, following the creation of an Ecology Section by park authorities. The section initiated the collection of insect and plants specimens, and prepared a plan for the Exhibit Center. In 1982 a mountain garden was established where a collection of plants from all over the park were transplanted. Since 1986 there has been an increased emphasis on research activities in the park. Projects on the Nepenthes villosa, Rafflesia and Paphiopedilum rothschildianum have received particular attention.

A Memorandum of Understanding between The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and The Sabah Parks was signed in June 1998. The aim of this is to "establish co-operative relations through mutual assistance in the areas of research and training". Additionally, its immediate aim is to "enlarge the representation in herberia of reference specimens of plants and fungus species found in Sabah’s parks.

Conservation Value

The nominated World Heritage Site contains "one of the richest and most diverse flora in the world", with as many as 6000 floral species occurring in the park, and high levels of endemism. Mount Kinabalu is considered a convergent point where Chinese and Himalayan genera meet with those from Australia, New Zealand and even American affinity. Approximately 608 species of [[fern]s] have been recorded in the park, more than for the whole of mainland tropical Africa. Many important Dipteroarp timber species are also represented. The park is identified as one of Malaysia’s Centers of Plant Diversity.

High species diversity is due to great altitudinal and climatic change range; precipitous topography causing effective geographic isolation over short distances; diverse geology with many localized edaphic condition, particularly the ultrafumic substrates; frequent climatic oscillations influenced by El Niño events and the geological history of the Malay Archipelago Diversity.

The site shows evidence of past geological activities that have created unique topographical features, has examples of significant on-going biological and ecological processes, as well as the evolution and development of terrestrial habitats; and possesses exceptional natural beauty. Indeed the Kinabalu plateau has been described as "a unique morphology that is different from other elevated plateaus in the wet tropics".

Conservation Management

A Management and Development Plan for the Sabah Parks, with particular emphasis on Kinabalu Park was commissioned in 1990 by the Board of Trustees of the Sabah Parks. This is the basic working document of the park, that identifies its purpose, natural values, management objectives and future development and management strategy. There are five main focus areas, these include: conserving biological and physical resources, spearheading scientific research and enhancing educational values, increasing recreational and tourist activities, preserving cultural and historical values and instituting management procedures to support other strategic thrusts.

The Enforcement of Parks Enactment, 1984 and Parks (Amendment) 1996 governs the control of Parks. Activities that contravene the outlined provisions may result in imprisonment for one to three years, and a fine of between RM 25,000 and RM100,000.

Management Constraints

Potential threats to the integrity of the nominated site currently arise from native rights, agriculture and climate change.

Several areas in the park have been claimed by adjacent villagers as "native customary rights" based on Section 15 of the Land Ordinance. The areas claimed are at five locations, and extend to approximately 2,000 ha. Fruit tree cultivation and burial ground form the basis of their claims. This is expected to become a pressure in future due to a growing population and a lack of available land elsewhere. Agricultural activities by villagers inside the park may also result in management concerns in future.

Mining activities have occurred at Mamut Copper Mine, located to the east of the Mt. Kinabalu, but have now ceased. Such activities have threatened water sources, particularly the Mamut River.

The region is subjected to periods of climatic extremes intensified by El Niño events. Droughts often result, frequently having effects on park vegetation. In 1997-1998 Sabah was affected by such an event. Forest fires broke out in a number of areas in the state, including 9 locations in the Park, covering a total area of 2,500 ha.

Visitor activities are mainly centered upon three main locations in the park, representing approximately 5% of the total area of the nominated site. Erosion, noise and litter problems exist, but are largely under control.

Staff

A total of 195 staff are employed at Kinabalu Park, 95 of which work in the Management and Operation Section, and 37 who are attached to the Research and Education Section. The Park Warden is responsible for the overall management and administration of activities in the park. The day to day administration of the park is undertaken by 1 assistant warden, 2 senior park rangers, 18 park rangers and 88 maintenance staff.

Budget

Financial support for the management and operations expenses of Kinanbalu Park is received via a grant administered to Sabah Parks. In 1998 the park received a grant of US$631,662. Other income is generated from entrance, climbing and accommodation fees, as well as fines. Total revenue generated in 1998 amounted to US$526,385. Total expenditure by the Management and Operations Section in 1998 was US$486,906, while the Research and Education Section spent US$247,728.

IUCN Management Category

- II (National Park)

- Natural World Heritage Site (proposed) – Criteria i, ii, iii iv

Further Reading

The nomination document for this site has a comprehensive reference list. The following are a selection of some of the key references used.

- Anon. 1998. Memorandum of Understanding Between Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, England, and Sabah Parks, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. 4pp.

- Beaman, J.H. 1996. Evolution and Phytogeography of the Kinabalu Flora. In: Wong, K.M. & Philips, A. (Eds.) Kinabalu Summit of Borneo. Sabah Society, Koto Kinabalu.

- Beaman, J.H. & Beaman, R.S. 1998. The Plants of Mount Kinabalu 3. Gymnosperms and Non-orchid Monocotyledons. Natural History Publications (Borneo) Sdn. Bhd., Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Malaysia and Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

- Buin, A. 1999. An Altitudinal Survey of the Birds of Mount Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. Sabah Parks Nature Journal. Vol. 2: 59-73.

- Chin, P.K. 1996. Fresh-water Fishes of Kinabalu and Surrounding Areas. In: Wong, K.M. & Phillips, A. (Ed.) Kinabalu Summit of Borneo. Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu. p333-351.

- Coppers and Lybrand Management Consultants Sdn Bhd and Sun Chong and Wong. 1992. The Kinabalu Park Development Masterplan Towards Sustained Development. Volume II. 110pp

- Coppers and Lybrand Management Consultants Sdn Bhd and Sun Chong and Wong. 1992. A Development Plan for Kinabalu Nature and Golf Resort. Volume III. 25pp

- IUCN. 1996. 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN Gland, Switzerland. 367pp.

- Jacobson, S.K. 1986. Kinabalu. Sabah Parks Publications No. 7. Koto Kinabalu: Sabah Parks.

- Kitayama, K. 1991. Vegetation of Mount Kinabalu Park Sabah, Malaysia: A Project Paper. Protected Areas and Biodiversity, Environment and Policy Institute. 45pp.

- Kitayama, K. et al. 1999. Climate Profile of Mount Kinabalu during late 1995 - early 1998 with special reference to the 1998 Drought. Sabah Parks Nature Journal. Vol. 2: 85-100.

- Komoo, I. 1997. Geomorfologi Glasier Penara Kinabalu. In: Warisan Geologi Malaysia: Geologi Pemuliharaan Untuk Ekopelancongan, University Kebangsaan Malaysia. p299-319.

- Kudo, G. & Kitayama, K. 1999. Drought effects on the summit vegetation Mount Kinabalu by an El Nino event in 1998. Sabah Parks Nature Journal, 2:101-110

- Lowry, J.B., Lee, D.W. and Stone, B.C. 1973. Effects of drought on Mount Kinabalu. Malay Nature Journal. 26: 178-179

- Mackinnon, J. & Philips, A. 1994. A Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 0198540345

- Nais, J. 1996. Kinabalu Park and the Surrounding Indigenous Communities. Working Paper No. 17, 1996. UNESCO, Paris.

- Smythies, B.E. 1996. Some Interesting Birds of Kinabalu Park. In: Wong, K.M. & Philips, A. (Eds.) Kinabalu Summit of Borneo. Sabah Society, Koto Kinabalu. 369-395p.

- Webster, P.J. & Palmer, T.N. 1997. The Past and Future of El Nino. Nature 390: 562-564.

- Wong, K.M. & Philips, A. (Eds.) Kinabalu Summit of Borneo. Sabah Society, Koto Kinabalu. 437pp.

- WWF & IUCN. 1994-1995. Centres of Plant Diversity - A guide and strategy for their conservation. 3 volumes. IUCN Publication Unit, Cambridge.