Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania

Contents

- 1 Introduction Kilimanjaro National Park (2°45'-3°25'S, 37°00'-37°43'E) is a World Heritage Site in the United Republic of Tanzania. At 5,963 meters (Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania) (m) Kilimanjaro is the highest point in Africa. This massive volcano stands in splendid isolation above the surrounding plains, with its snowy peak looming over the savanna. The mountain is encircled by mountain forest. Numerous mammals, many of them endangered species (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered), live in the Park.

- 2 Geographical Location

- 3 Date and History of Establishment

- 4 Area

- 5 Land Tenure

- 6 Altitude

- 7 Physical Features

- 8 Climate

- 9 Vegetation

- 10 Fauna

- 11 Local Human Population

- 12 Visitors and Visitor Facilities

- 13 Scientific Research and Facilities

- 14 Conservation Value

- 15 Conservation Management

- 16 IUCN Management Category

- 17 Further Reading

Introduction Kilimanjaro National Park (2°45'-3°25'S, 37°00'-37°43'E) is a World Heritage Site in the United Republic of Tanzania. At 5,963 meters (Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania) (m) Kilimanjaro is the highest point in Africa. This massive volcano stands in splendid isolation above the surrounding plains, with its snowy peak looming over the savanna. The mountain is encircled by mountain forest. Numerous mammals, many of them endangered species (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered), live in the Park.

Geographical Location

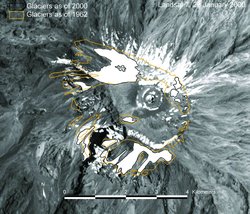

The Kilimanjaro icecap in 1962 (yellow), and 2000 (black outline). (Source: Kilimanjaro: Christian Lambrechts, UNEP-DEWA)

The Kilimanjaro icecap in 1962 (yellow), and 2000 (black outline). (Source: Kilimanjaro: Christian Lambrechts, UNEP-DEWA) The National Park and Forest Reserve on Mount Kilimanjaro lie very near the border between Tanzania and Kenya north of Moshi in the north centre of the country. The National Park comprises the whole of the mountain above 2,700 m, including some of the montane forest, and six corridors through the forest belt below. The area lies at 2°45'-3°25'S, 37°00'-37°43'E.

Date and History of Establishment

- 1910s: Mt. Kilimanjaro and its [[forest]s] declared a game reserve by the German colonial government;

- 1921: The area was gazetted as a forest reserve, confirmed by subsequent legislation;

- 1973: The mountain above the tree line (~2,700m) reclassified as a National Park by Government Notice 50 and opened to public access in 1977.

Area

National Park: 75,353 hectares (ha), surrounded by a Forest Reserve of 107,828 ha.

Land Tenure

Government, in Kilimanjaro province. Administered by Tanzania National Parks Authority.

Altitude

1,830 m (Marangu Gate) to 5,895 m (Kibo,Uhuru Peak).

Physical Features

Kilimanjaro is a giant stratovolcano and one of the largest [[volcano]es] in the world. It is the highest mountain in Africa, rising 4,877 m above the surrounding savanna plains to 5,895 m and covers an area of about 388,500 ha. It stands alone but is the largest of an east-west belt of volcanoes across northern Tanzania. It has three main volcanic peaks of varying ages lying on an east-southeast axis, and a number of smaller parasitic cones. To the west, the oldest peak Shira (3,962 m) of which only the western and southern rims remain, is a relatively flat upland plateau of some 6,200 ha, the northern and eastern flanks having been covered by later material from Kibo. The rugged erosion-shattered peak of Mawenzi (5,149 m) lies to the east. The top of its western face is fairly steep with many crags, pinnacles and dyke swarms. Its eastern side falls in cliffs over 1,000 m high in a complex of gullies and rock faces, rising above two deep gorges, the Great Barranco and the Lesser Barranco. Kibo (5,895 m), is the most recent summit, having last been active in the Pleistocene and still has minor fumaroles. It consists of two concentric craters of 1.9 x 2.7 kilometers (km) and 1.3 km in diameter with a 350 m deep ash pit in the center. The highest point on the mountain is the southern rim of the outer crater. Between Kibo and Mawenzi there is a plateau of some 3600 ha, called the Saddle, which forms the largest area of high altitude tundra in tropical Africa. There are deep radial valleys especially on the western and southern slopes.

The mountain is a combination of both shield and volcanic eruptive structures. Over time different flows have produced a variety of different rock types. The predominant rock types on Shira and Mawenzi are trachybasalts; the later lava flows on Kibo show a gradual change from trachyandesite to nephelinite. There is also a number of intrusions such as the massive radial and concentric dyke-swarms on Mawenzi and the Shira Ridge and groups of nearly 250 parasitic cones chiefly formed from cinder and ash. Since 1912, the mountain has lost 82% of its ice cap and since 1962, 55% of its remaining glaciers. Kibo still retains permanent ice and snow and Mawenzi also has patches of semi-permanent ice, but the mountain is forecast to lose its ice cap within 15 years. Evidence of past glaciation is present on all three peaks, with morainic debris found as low as 3,600 m. The mountain remains a critical water catchment for both Kenya and Tanzania but as a result of the receding ice cap and deforestation, several rivers have dried up, affecting the [[forest]s] and farmland below.

Climate

There are two wet seasons, November to December and March to May, with the driest months between August to October. Rainfall decreases rapidly with increase in altitude; mean precipitation is 2,300 millimeters (mm) in the forest belt (at 1,830 m), 1,300 mm at Mandara hut on the upper edge of the forest (2,740 m), 525 mm at Horombo hut in the moorland (3,718 m), and less than 200 mm at Kibo hut (4,630 m), giving desert-like conditions. The prevailing winds, influenced by the trade winds, are from the southeast. North-facing slopes receive far less rainfall. January to March are the warmest months. Conditions above 4,000 m can be extreme and the diurnal temperature range]there is considerable. Mist frequently envelopes much of the massif but the former dense cloud cover is now rare.

Vegetation

Sunset over Mawenzi Peak on Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, January 18, 2000. (Sources: AP Images and U.S. State Department)

Sunset over Mawenzi Peak on Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, January 18, 2000. (Sources: AP Images and U.S. State Department) The mountain has five main vegetation zones: savanna bushland at 700-1,000 m (south slopes) and 1,400-1,600 m (north slopes), densely populated sub-montane agro-forest on southern and southeastern slopes, the montane forest belt, sub-alpine moorland and alpine bogs. Above this is alpine desert. The montane forest belt circles the mountain between 1,300 m (~1,600 m on the drier north slopes) to 2,800 m. Forests above 2,700 m are within the National Park. According to Lambrechts et al. there are 2,500 plant species on the mountain, 1,600 of them on the southern slopes and 900 within the forest belt. There are 130 species of trees with the greatest diversity being between 1,800 and 2,000 m. There are also 170 species of shrubs, 140 species of epiphytes, 100 lianas and 140 pteridophytes.

The forest between 1,000 and 1,700 m in the south and east has been extensively farmed with remnants of natural forest left only in deep gorges. Dominant species of the submontane forest between 1,300-1,600 m in the west and 1,600-2,000 m in the north are Croton megalocarpus and Calodendron capense; and of the lower to middle montane forest between 1,600-2,200 m in the west and 2,000-2,400 m in the north is Cassipourea malosana. On the southern and southeastern slopes from 1,600 to 2,100 m the dominant lower montane forest species is camphorwood Ocotea usambarensis; from 2,100 to 2,40 0m the dominant middle montane forest species are camphorwood Ocotea usambarensis with yellowwood Podocarpus latifolius, a large evergreen, with the tree fern Cyathea manniana, sometimes growing to 7 m high. From 2,400 to 2,800 m the dominant upper montane forest species are Podocarpus latifolius with Ocotea usambarensis. The subalpine southern and southeastern slopes between 2,800-3,100 m have forest of Hagenia abyssinica with Podocarpus latifolius and Prunus Africana; and on the north slopes Juniperus procera - Podocarpus latifolius forest with Hagenia abyssinica. Above 2,800 m to the edge of the tundra at 3,500 m is Erica excelsa forest.

There is no bamboo zone, nor a Hagenia-Hypericum zone. Above about 4,600 m, very few plants are able to survive the severe conditions, although specimens of Helichrysum newii have been recorded as high as 5,760 m (close to a fumarole), and mosses and lichens are found right up to the summit. The upland moor consists primarily of heath/scrub plants, with Erica excelsa, Philippia trimera, Adenocarpus mannii, Protea kilimandscharica, Stoebe kilimandscharica, Myrica meyeri-johannis, and Myrsine africana. Grasses are abundant in places, and Cyperaceae form the dominant ground cover in wet hollows. On flatter areas between the upland moor and the forest edge are areas of moorland or upland grassland composed of Agrostis producta, Festuca convoluta, Koeleria gracilis , Deschampsia sp., Exotheca abyssinica, Andropogon amethystinus, and A. kilimandscharicus, with scattered bushes of Adenocarpus mannii, Kotschya recurvifolia and Myrica meyeri-johannis. Various species of Helichrysum are found in the grasslands and in the upland moor. Two distinct forms of giant groundsel occur on the upper mountain: Senecio johnstonii cottonii, endemic to the mountain and only occurring above 3,600 m, and S.johnstonii johnstonii which occurs between 2,450 m and 4,000 m, and shows two distinct forms. At all altitudes Senecio favors the damper and more sheltered locations, and in the alpine bogs is associated with another conspicuous plant, growing up to 10 m tall, the endemic giant lobelia Lobelia deckenii. Below the tree line, the park includes six corridors through the forest to the mountain foot.

Fauna

The whole mountain including the montane forest belt, part of which extends into the National Park, is very rich in species: 140 mammals, (87 forest species), including 7 primates, 25 carnivores, 25 antelopes and 24 species of bat. Above the treeline at least seven of the larger mammal species have been recorded, although it is likely that many of these also use the lower montane forest habitat. The most frequently encountered mammals above the treeline are Kilimanjaro tree hyrax Dendrohyrax validus (VU), grey duiker Sylvicapra grimmia and eland Taurotragus oryx, which occur in the moorland, with bushbuck Tragelaphus scriptus and red duiker Cephalophus natalensis being found above the treeline in places, and buffalo Syncerus caffer occasionally moves out of the forest into the moorland and grassland. An estimated 220 elephants Loxodonta africana (EN) are distributed between the Namwai and the Tarakia Rivers and sometimes occur on the higher slopes. Insectivores occur and rodents are plentiful above the tree line, especially at times of population (Population growth rate) explosion, although golden moles (Chrysochloridae) are absent. Three species of primate are found within the montane forests, blue monkey Cercopithecus mitis, western black and white colobus Colobus polykomos abyssinicus, and bushbaby Galago sp. and among mammals found there are leopards Panthera pardus, as well as some of the species listed above. Abbot's duiker Cephalophus spadix (VU) is restricted to Kilimanjaro and some neighboring mountains. Black rhinoceros Diceros bicornis (CR) is now extinct in the area and mountain reedbuck Redunca fulvorufula is probably extinct.

Although 179 highland bird species have been recorded for the mountain, species recorded in the upper zones are few in number, although they include occasional lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, mainly on the Shira ridge, hill chat Cercomela sordida, Hunter's cisticola Cisticola hunteri, and scarlet-tufted malachite sunbird Nectarinia johnstoni. White-necked raven Corvus albicollis is the most conspicuous bird species at higher altitude. The forest has several notable bird species including Abbot's starling Cinnyricinclus femoralis, which has a very restricted distribution. The butterfly Papilio sjoestedti, sometimes known as the Kilimanjaro swallowtail, is restricted to Kilimanjaro, Ngorongoro and Mount Meru, although the subspecies P.atavus is found only on Kilimanjaro.

Local Human Population

The area surrounding the mountain is quite heavily populated principally by the Chagga people and the northern and western slopes of the Forest Reserve surrounding the National Park has 18 medium to large 'forest villages'. Although it is illegal these people still use the forest for many household and medicinal products, for fuelwood, small scale farming, beekeeping, hunting, charcoal production and logging. Some 12% of the forest is plantation, some almost reaching to the moorland. The shamba system of tree plantations interplanted with crops comprises over half the planted area but over half of it is not replanted with trees at all.

Visitors and Visitor Facilities

The National Park has been developed with tourism in mind, and approximately 10,800 people visit the park each year. The mountain can be climbed by non-climbers and the tour is increasing in popularity. All visitors climbing the mountain must have a guide preferably from a licensed tour operator and take precautions against mountain sickness. Although there are six routes up the mountain, 91% of all hikers use the Marangu Trail. There are three huts for climbers on this trail: Mandara, Horombo and Kibo. Food, bedding and porters are provided by tour operators. There is a mountain rescue team at the park headquarters and at each of the huts At Marangu there are a lodge, a hostel, a shop and equipment rental.

Scientific Research and Facilities

A variety of scientific studies have been conducted within the park, although there are no special facilities. There has been long-term geological, hydrological and vulcanological research by the Geology Department of the University of Tanzania and Sheffield University in the United Kingdom which is of particular interest. There is potential for further work, particularly in relation to glaciology and world climate. The College of African Wildlife Management at Mweka, and its facilities, is relatively close.

Conservation Value

With its snow-capped peak standing alone almost 5 km above the surrounding plains Mt. Kilimanjaro is a superlative natural feature and a powerful symbol of the country. It is also an essential water catchment for the surrounding countryside and protects wildlife and a unique endemic flora.

Conservation Management

Although protection is total within the park, and access is restricted, management is still not entirely adequate. A management plan, prepared in 1993, outlines the following objectives: to protect and maintain the park's natural resources; to increase interpretation and visitor information; to encourage visitor use and development in a sustainable fashion; to improve park operations; and to strengthen the park's relationship with local communities. A number of boundary adjustments and land protection strategies were described. These include gazetting forest reserve lands to the National Park with the exception of the pine and cypress plantations and the half-mile strip below the forest, which would be returned to village government control under sustained yield practices to provide local resource benefits; initiating an 'Integrated Regional Conservation Plan' to lessen the local community's dependence on the mountain's forest resources; gazetting the portion of Lake Chala within Tanzania into the National Park; and reaffirming and encouraging full implementation of Mounduli District Council bylaws to provide complete protection for the North Kilimanjaro Migration Corridor. A zoning scheme, defining limits of acceptable use, has been implemented for the National Park and Forest Reserve areas. Seven zones have been identified: intensive use hiking zone (2,700 ha), low use hiking zone (summit- bound) (7,723 ha), low use hiking zone (non-summit bound) (3,750 ha), day use zone (598 ha), wilderness zone (150,657 ha), mountaineering zone (2,510 ha), cultural protection zone (259 ha), and administration zone (62 ha).

Management Constraints

As in many other parks and reserves in Africa, resources are stretched, and manpower and equipment are not sufficient for full implementation of the management plan. Within the forest reserve exploitive activity has continued, although this was curtailed by Presidential Decree in 1984 and the issuing of timber licenses has been stopped. Most difficulties are encountered in the management and protection of the montane forest, with illegal hunting, honey gathering, felling, fuel wood collection, grass burning and incursions by domestic livestock, particularly in the south-west. Both honey gathering and grass burning result in outbreaks of uncontrolled fires every year, particularly during the dry season and in the south-west. It occurs even on the moorland edge and quite extensively within the Erica heathland. As with moorland in many parts of the world, fire is almost certainly one of the factors that has influenced the mountain biota for hundreds of years, and management (or non-management) of fire is likely to continue presenting problems. Tomlinson expressed concern that the frequency of fire on the Shira Plateau was increasing, and that this might pose a threat to the populations of giant groundsel.

There is still a major problem of illegal deforestation especially of camphorwood trees below 2,500 m. This has led to widespread landslides: 88 were recorded by Lamprechts et al.,2002. The forest buffer zone is being maintained in six corridors within the park, but elsewhere felling has continued, and there has been some replacement with commercial plantations or maize crops, although this has been halted at least temporarily by the 1984 Presidential Decree. Problems have also resulted from the increasingly heavy use of the area by tourists. The gradual drying up of mountain rivers is threatening the forest and farmland dependent on them.

Staff

There is a total of 156 staff, including one Chief Park Warden, one Senior Park Warden and two park wardens.

Budget

Kilimanjaro was reported in 1984, to be the only park in Tanzania which approached self-sufficiency, paying for much of its administrative and management costs from the revenue accruing from tourism and this is still the case. The park no longer receives subsidiaries from the government, although assistance is provided by other local and foreign organizations.

IUCN Management Category

- II (National Park)

- Natural World Heritage Site inscribed in 1989. Natural Criterion iii

Further Reading

- Allan, I. (ed). (1991). Guide to Mt. Kenya and Kilimanjaro. The Mountain Club of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya. (Unseen). ISBN: 9966986030.

- Byarugaba, K. (1988). Report on the Threat Posed by Settlements and Human Activities on Arusha, Lake Manyara, Tarangire and Kilimanjaro National Parks. National Land Use Planning Commission, Dar es Salaam. 21 pp. (Unseen).

- Child, G. (1965). Some notes on mammals of Mount Kilimanjaro. Tanganyika Notes and Records 64: 77-89.

- Coutts, H. (1969). Rainfall of the Kilimanjaro area. Weather 24: 66-69.

- Gilbert, V. (1970). Plants of Kilimanjaro. Typed report. Office of Environmental Interpretation, U.S. National Park Service, Washington D.C.

- Greenway, P.(1965). The vegetation and flora of Mt. Kilimanjaro. Tanganyika Notes and Records 64.

- Grimshaw,J., Cordeiro, N. & Foley C. (1995). The mammals of Kilimanjaro. Journal of East African Natural History 84: 105-139.

- Hutchinson, J. (1965). Kilimanjaro. Tanzania Notes and Records 64. Special issue.

- Lambrechts, C.,Woodley, B.,Hemp, A. Hemp, C.,Nyiti, P (2002). Aerial Survey of the Threats to Mt. Kilimanjaro Forests. UNDP, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

- Lamprey, H. (1965). Birds of the forest and alpine zones of Kilimanjaro. Tanganyika Notes and Records 64: 69-76.

- Morris, B. (1970). The zonal vegetation of Kilimanjaro. African Wildlife 24 pp.

- Mwasaga, B. (1983). Vegetation/Environment Relationships, Kiraragua Catchment Area, Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. MSc Thesis, University of Dar es Salam.

- National Park Service (1967). Kilimanjaro; Survey for Proposed Mount Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania, East Africa. Survey conducted by the U.S. National Park Service for the United Republic of Tanzania.

- Salt, G. (1954). A contribution to the ecology of Upper Kilimanjaro. Journal of Ecology 42: 375-423.

- Sampson, D. (1965). The geology, volcanology and glaciology of Kilimanjaro. Tanganyika Notes and Records 64: 118-124.

- Tanzania National Parks/African Wildlife Foundation (1987). Mount Kilimanjaro National Park Tanzania National Parks, Arusha.

- Tanzania National Parks (1993). Kilimanjaro National Park General Management Plan. Tanzania National Parks, Arusha. 188 pp.

- Tomlinson, R. (1985). Observations on the giant groundsels of upper Kilimanjaro. Biological Conservation 31: 303-316.

- Wilcockson, W. (1956). Preliminary notes on the geology of Kilimanjaro. Geol. Mag. 93(3): 218-228.

- Wilkinson, P. (1954). Preliminary note on the state of volcanicity of Kilimanjaro. Geol. Survey, Tanganyika.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |

1 Comment

Peter Howard wrote: 01-27-2011 23:03:11

Readers may want to visit the African Natural Heritage website to view a selection of images and map of the Kilimanjaro National Park world heritage site, and follow links to Google Earth and other relevant web resources: http://www.africannaturalheritage.org/Kilimanjaro-National-Park-Tanzania.html