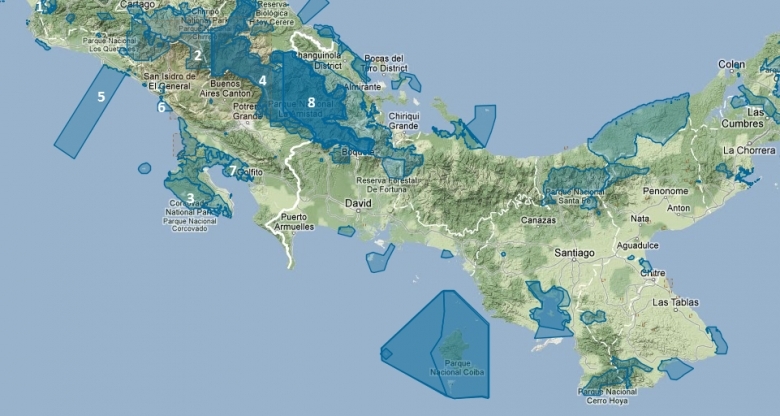

Isthmian-Pacific moist forests

Covering the lowland Pacific slopes at mainly 500 meters elevation in southern and central Costa Rica, and northern to central coastal Panama, the Isthmian-Pacific Moist Forests originally represented lowland expanses of wet tropical jungle. This forest ecoregion evolved from unique combinations of North American and South American flora and fauna, which came together with the joining of these continents three million years ago. The resultant mixing has produced one of the richest and most diverse assemblages of plants and animals of any area of comparable size. However, most of this ecoregion has been converted to subsistence and commercial agriculture. Large acreages of land are presently devoted to cattle grazing, coffee plantations and other crops.

Location and general description

This ecoregion is located at the juncture of Central and South America. Rainfall ranges from approximately 2500 millimeters per annum in central Panama to higher levels in Costa Rica. These forests can be distinguished from the cooler subtropical moist forests to the north by their distinct geologic history and consistent annual temperatures above 24 degrees Celsius.

Until recent geologic times, the isthmus south of central Nicaragua was discontinuous, volcanically active and topographically and environmentally diverse. Basalt bedrock is the parent material of much of the residual and often unconsolidated soils covering the hilly areas of this ecoregion.

This ecoregion is characterized by a tropical evergreen forest with considerable elements of palm species, although the landscape suffers from severe habitat loss and habitat fragmentation due to agricultural conversions. The original palm component includes many subcanopy and understory species including Welfia georgii and Socratea exorrhiza, and in permanently flooded areas, Raphia taedigera. Seasonal swamp forests occur in the lowest and flattest areas of Costa Rica, particularly along the coast where they grade into mangrove forests. In these forests, Gavilán (Pentaclethra macroloba) can dominate the canopy. The ecocode for this region is NT0130.

Biodiversity features

While biologically very diverse, this ecoregion supports modest levels of endemism. There are a total of 811 different vertebrate taxa in the ecoregion. The high species richness is derived in great part from the mixing of North and South American floras and faunas on this land bridge several million years ago. The resident fauna, including butterfly, reptile, amphibian, bird, and mammalian taxa are for the most part wide-ranging representative species of a wet tropical forest ecoregion that extends from southern Mexico to northern South America. Strict endemism among fauna is almost non-existent: between 80-100% of the mammalspecies that occur in northern Costa Rica also occur in Panama, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Colombia. However, a number of restricted range birds are shared with the moist forests ecoregion to the north, together forming an Endemic Bird Area.

Endemic amphibians to the ecoregion are the airstrip caecilian (Oscaecilia osae), a species known only from the Península de Osa in southwestern Costa Rica; the golfito robber frog (Eleutherodactylus taurus); the Endangered Golfoducean poison frog (Phyllobates vittatus) known from the lowlands of the Golfo Dulce region of southwestern Costa Rica and the vicinity of the city of Dominical in the Provincia de Puntarenas of Costa Rica; Porthidium volcanicum and Oedipina alleni.

Endemic reptiles for the ecoregion are Blair's bachia (Bachia blairi), Savage's earth snake (Geophis downsii), Panamanian earth snake (Geophis championi) and Lachesis melanocephalus.

Bird species endemic to the ecoregion are: the Near Threatened Baird's trogon (Trogon bairdii), the black-hooded antshrike (Thamnophilus bridgesi), the Vulnerable brown-backed dove (Leptotila battyi), the charming hummingbird (Amazilia decora), the coiba spinetail (Cranioleuca dissita), the garden emerald (Chlorostilbon assimilis), the Vulnerable great currasow (Crax rubra).

Endemic mammals to the Isthmian-Pacific moist forests are represented by the Underwood's pocket gopher (Orthogeomis underwoodi).

Threatened non-endemic mammalian species within the ecoregion are the Endangered Central American spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) , the Vulnerable Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii), the Vulnerable giant anteater (Myrmecophega tridactyla), the Near Threatened tailless bat (Anoura cultrata), the Vulnerable lemurine night monkey (Aotus lemurinus), the Near Threatened Talamanchan yellow-shouldered bat (Sturnira morax), the Vulnerable Talamanchan small-eared shrew (Cryptotis gracilis), the Near Threatened white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), the Near Threatened yellow isthmus bat (Isthmomis flavidus), the Near Threatened spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum) and the Near Threatened margay (Leopardus wiedii).

Special status non-endemic reptiles found in the ecoregion are the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), the Lower Risk/Near Threatened common slider (Trachemys scripta), the Vulnerable olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) and the Critically Endangered leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea).

Non-endemic threatened avian species found here are: the Endangered black-cheeked ant tanager (Habia atrimaxillaris) , the Vulnerable cerulean warbler (Dendroica cerulea), the Near Threatened crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis), the Near Threatened elegant tern (Sterna elegans), the Near Threatened golden winged warbler (Vermivora crysoptera), the Near Threatened harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), the Near Threatened olive-sided flycatcher (Contopus cooperi), the Near Threatened painted bunting (Passerina ciris) and the Endangered yellow-billed cotinga (Carpodectes antoniae).

Special status non-endemic amphibians in the ecosystem are the Vulnerable camron mushroomtongued salamander (Bolitoglossa lignicolor), the Endangered horned marsupial frog (Gastrotheca cornuta), the Near Threatened Kerferstein's worm salamander (Oedipina uniformis), the Endangered Legler's stream frog (Ptychohyla legleri), the Vulnerable Mexican caecilian (Demophis mexicanus) and the Critically Endangered Veragoa's stubfoot toad (Atelopus varius).

Few large expanses of primary rainforest remain intact, occurring only in large reserves, particularly in eastern Panama along La Amistad International Park. These blocks retain nearly all vertebrate species of this ecoregion, including most large predators though increasing isolation threatens their long-term viability. Logging and clearing of remaining forests threaten many species of slow-growing trees. Scarlet macaws (Ara macao) nest in the lowland forests.

Protected areas

There are a number of protected areas in this ecoregion:

- Carara National Park

- Chirripó National Park

- Corcovado National Park

- La Amistad International Park

- Manuel Antonio National Park

- Marino Ballena National Park

- Piedras Blancas National Park

- Reserva de la Biosfera de la Amistad Biosphere Reserve

Current status

Although a few large blocks of intact habitat still exist, the once vast Pacific lowland forests have been seriously fragmented over the last several decades by deforestation and agricultural conversion. The tropical evergreen forests are among the least well represented in Costa Rica's protected areas system. Most lowland wet forest parks are too small and isolated to maintain viable populations of large-ranging faunal species.

The lack of protection of the Pacific lowlands and the heavy bias toward deforestation at elevations less than 1000 meters in elevation contribute to the fragmentation and elimination of these forests. With gradual slopes and relatively good access, much of Costa Rica's remaining Pacific slope forest has been intervened or exists in small fragments. In the case of Panama, the earliest European settlers first extended their supply routes through this ecoregion on the gentle Pacific slopes, initiating two centuries of degeneration of this habitat.

Types and severity of threats

Flat areas with alluvial soils are under coffee and palm wine cultivation, while the less fertile hilly basaltic soils have more recently been logged and converted to cattle pasture. New access roads, malaria control, and incentives for migration to these areas in the last few decades have encouraged settlement and resource extraction from the area. The last remaining intact forests in this ecoregion are currently under tremendous logging pressure and are being felled, rapidly. Squatting and other property claims are resulting in unregulated destruction in many areas despite the legislation in place to protect forests. Clear-cuts have even been made illegally within many parks.

While future threats in this ecoregion vary among the three countries, destruction of forest habitat through logging and conversion to cattle pasture are the most widespread and significant. Illegal logging and squatting is making in-roads into the remaining large forest blocks, while in the already fragmented Costa Rican forests; the principal threat is clearing for cattle production. In Panama, the Pacific slopes are steeper and somewhat less likely to be converted to agriculture; however, new roads in this region will certainly increase human settlement and cutting of accessible forests. Several regional conservation projects aim to enhance connectivity among the Pacific slope habitats, may provide some needed support for new or expanded protected areas or for payments for environmental services provided by private lands.

Justification of ecoregion delineation

The delineation’s for this [[ecoregion]were] derived from two separate national vegetation maps. In Costa Rica we followed the delineation’s of life zones by Tosi. In this case we lumped the following ecoregion of the Pacific slope catchment, south of the Central Valley: Tropical Wet Forest, Premontane Wet Forest, Tropical Moist Forest (TMF), TMF Perhumid Province Transition, and TMF Premontane Transition Belt. The western delineation is marked by either the continental divide or where it abuts to montane forests at higher elevations. In Panama we relied on the UNDP vegetation map, again, lumping the following lowland and premontane moist forest components on the southern portion of the continental divide: Tropical Moist Forest, Premontane Rain Forest, and Tropical Wet Forest. The northern delineation, which separates this ecoregion from the Central American moist forests to the north due to distinct species associations and seasonal climatic factors. This ecoregion also hosts several endemic species.

Further reading

- Baldospino, I. 1999. Personal communication.

- For a terser summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

- Barborak, J. R., A. F. Carr III, and L. D. Harris. 1994. Recomendaciones para la consolidación territorial y conectividad de las áreas protegidas de Costa Rica. In A. Vega, editor, Corredores Conservacionistas en la Región Centroamericana: Memorias de una Conferencia Regional auspiciada por el Proyecto Paseo Pantera. Florida: Tropical Research and Development, Inc.

- Clark, K. L., R. O. Lawton, and P. R. Butler. 2000. The Physical Environment. In N. M. Nadkarni, and N. T. Wheelwright, editors, Monteverde: Ecology and conservation of a tropical cloud forest. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Correa, M. 1999. Personal communication.

- Davis, S.D., V.H. Heywood, O. Herrera MacBryde, J. Villa-Lobos and A.C. Hamilton, editors. 1997. Centres of Plant Diversity. A Guide and Strategy for their Conservation. Volume 3. The Americas. IUCN Publications Unit, Cambridge, U.K. 562 pp.

- Delgado, F. 1985. Present situation of the forest birds of Panama. In A. W. Diamond, and T. E. Lovejoy, editors, Conservation of tropical forest birds. ICBP Technical Publication No. 4. UK.: International Council for Bird Preservation.

- DeVries, Philip. 1987. The butterflies of Costa Rica and their natural history. Volumes 1 and 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN: 0691028893.

- Dinerstein, E., D. Olson, D. Graham, A. Webster, S. Primm, M. Bookbinder, and G. Ledec. 1995. A conservation assessment of the terrestrial ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington DC.: World Wildlife Fund-US.

- Gómez, L.D., editor. 1986. La vegetación de Costa Rica (map series). Vol. I. In Vegetación y clima de Costa Rica. Ed. UNED. Costa Rica. cited in García, R. 1997. Biología de la conservación y áreas silvestres protegidas: situación actual y perspectivas en Costa Rica. INBio. Costa Rica.

- Haber, W. A. 2000. Plants and vegetation. In N. M. Nadkarni, and N. T. Wheelwright, editors, Monteverde: Ecology and conservation of a tropical cloud forest. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hartshorn, G. S., and L. J. Poveda. 1983. Checklist of trees. In D. H. Janzen, (editor), Costa Rican natural history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mendez, E. 1994. Estado de la Cde la Biodiversidad en Panamá. In A. Vega, editor, Corredores conservacionistas en la región Centroamericana: Memorias de una * Conferencia Regional auspiciada por el Proyecto Paseo Pantera. Florida: Tropical Research and Development, Inc.

- Palminteri, S., G. Powell, A. Fernandez, and D. Tovar. 1999. Talamanca Montane-Isthmian Pacific Ecoregion-Based conservation plan: Preliminary reconnaissance phase. Report to WWF-Central America.

- Powell, G. 1999. Limits to using ecological classification schemes to assess biodiversity representation. Presentation at Society for Conservation Biology annual meeting.

- Powell, G., J. Barborak, and M. Rodriguez. 2000. Assessing representativeness of protected natural areas in Costa Rica for conserving biodiversity: a preliminary gap analysis. Biological Conservation 93 (2000) 35-41.

- Quesada, F., Q. Jiménez, N. Zamora, R. Aguilar, and J. González. 1997. Arboles de la Peninsula de Osa. Costa Rica: INBio.

- Reid, F. 1997. A field guide to the mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 0195064011.

- Ridgely, R. 1976. A guide to the birds of Panama. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN: 0691025126.

- Stattersfield, A.J., M.J. Crosby, A.J. Long, and D.C. Wege (in press). A global directory of Endemic Bird Areas. BirdLife Conservation Series. BirdLife International, Cambridge, U.K.

- Stiles, F. G. 1985. Conservation of forest birds in Costa Rica: problems and perspectives. In A. W. Diamond, and T.E. Lovejoy, editors, Conservation of tropical forest birds. ICBP Technical Publication No. 4. UK: International Council for Bird Preservation.

- Stiles, F. G., and A. F. Skutch. 1989. A guide to the birds of Costa Rica. New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN: 0713635126.

- Stiles, F. G. and D. A. Clark. 1989. Conservation of tropical rain forest birds: a case study from Costa Rica. in American birds. Vol. 43. No. 3. UK.: International Council for Bird Preservation.

- Tosi Jr., J.A. 1969. Republica de Costa Rica: mapa ecológico. Map 1:750,000. Tropical Science Center,San Jose, Costa Rica.

- UNDP. 1970. Mapa ecólogico de Panama. Map 1:5,000,000. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, Panama City, Panama.

- Young, B. E., G. Sedaghatkish, E. Roca, and Q. Fuenmayor. 1999. El estatus de la conservación de la herpetofauna de Panamá. Resumen del Primer Taller Internacional sobre la Herpetofauna de Panama. The Nature Conservancy y Asociación Nacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (ANCON).

- Villalobos N.Zamora . 2010. Fabaceae. En: Manual de Plantas de Costa Rica. Vol. 5. B.E. Hammel, M.H. Grayum, C. Herrera & N. Zamora (eds.). Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 119: 395–775.

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |