Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic

This is Section 3.6 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Authors: Henry Huntington, Shari Fox; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Igor Krupnik; Case Study Authors are identified on specific case studies; Consulting Authors: Anne Henshaw,Terry Fenge, Scot Nickels, Simon Wilson

This chapter (of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment) reviews observations of the environmental changes occurring in the Arctic as well as the ways in which people view those changes. In both cases, there is a growing but still insufficient body of research to draw on. For some areas, such as the central and eastern Russian Arctic, few or no current records of indigenous observations are available.To detect and interpret climate change, and to determine appropriate response strategies, more research is clearly needed.

In terms of indigenous observations, documentation of existing knowledge about changes that have occurred and prospective monitoring for future change are both important[1]. More research on knowledge documentation has taken place in Canada, particularly among Inuit, regarding indigenous knowledge of climate change than elsewhere[2], but even there a great deal more can be done. In Eurasia and Greenland, little systematic work of this kind has been done, and research in these regions is clearly needed[3]. Indigenous observation networks have been set up in Chukotka, Russia[4], and some projects have taken place in Alaska[5], but again, little systematic work has been done to set up, maintain, and make use of the results from such efforts.

In terms of indigenous perspectives and interpretations of climate change, most research has taken place in Canada[6], building largely on the documentation of observations noted above.To date, however, little has been done to connect these perspectives to potential response strategies (see Table 3.1). Some research on responses has been undertaken recently or is underway in Alaska[7], but more is needed to determine the needs of those designing response strategies, the ways in which information is used in the process of designing them, and the ways in which researchers and indigenous peoples can contribute.

Table 3.1. Indigenous responses to climate change in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of Canada’s Northwest Territories (adapted from Nickels et al.[8]).

|

Observation |

Effect |

Response/adaptation |

|

Erosion of the shoreline |

Relocation of homes and possibly community considered |

Stone breakwalls and gravel have been placed on the shoreline to alleviate erosion from wave action |

|

Warmer temperatures in summer |

Not able to store country food properly and thus not able to store it for use in winter |

Community members travel back to communities more often in summer to store country food.This is expensive as it requires more fuel and time |

|

Warmer temperatures in summer |

Can no longer prepare dried/smoked fish in the same way, it gets cooked in the heat |

People are building thicker roofs on the smoke houses to keep some heat out, tarpaulins and other materials are used to shelter country foods from heat |

|

Lower water levels and some brooks drying up |

Not as many good natural sources of drinking water available |

Bottled water now taken on trips |

|

Changing water levels and the formation of shifting sand bars |

More difficult to plan travel in certain areas |

Community members are finding new (usually longer and therefore more costly) routes to their usual camps and hunting grounds or are flying, incurring still greater expense |

|

Warmer weather in winter |

Animal fur is shorter and not as thick, changing the quality of the fur/skin used in making clothing, decreasing the money received when sold |

Some people do not bother to hunt/trap, while others buy skins from the store that are not locally trapped, are usually not as good quality, and are expensive |

|

Water warmer at surface |

Kills fish in nets |

Nets are checked and emptied more frequently so that fish caught in nets do not perish in the warm surface water and spoil |

|

More mosquitoes and other biting insects |

Getting bitten more |

Use insect repellent lotion or spray as well as netting and screens for windows and entrances to houses |

|

Changing animal travel/migration routes |

Makes hunting more expensive, requires more fuel, gear, and time – high costs mean some residents (particularly elders) cannot afford to go hunting |

Initiation of a community program for elders, through which younger hunters can provide meat to elders who are unable to travel or hunt for themselves |

An essential component of this line of research is to understand how various actors see the issue of climate change, why they see it the way they do, and what can be done to arrive at a common understanding of the threat posed by climate change, the need for responses, and the needs and capabilities of local residents. Consideration of regional similarities and differences across the Arctic may help communities to learn from each other’s experiences, too, as well as to incorporate greater understanding of the cumulative impacts of various factors influencing communities (see Chapter 17 (Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic)). In working toward this goal, an often neglected topic is the linking of indigenous and scientific observations of climate change and the interpretation of these observations. Proponents of the documentation and use of indigenous knowledge often stress both similarities and differences with scientific knowledge[9], but little is done to bridge the gap[10]. While the two approaches differ in substantive ways, there are examples of how interactions between them can benefit both and produce a better overall understanding of a given topic[11]. Part of the problem is in determining how indigenous knowledge can best be incorporated into scientific systems of knowledge acquisition and interpretation. Part of the problem is in finding ways to involve indigenous communities in scientific research as well as in communicating scientific findings to indigenous communities. And a large part of the problem is in establishing the trust necessary to find appropriate solutions to both goals.

Collaborative research is the most promising model for addressing these challenges, as demonstrated by the projects through which the case studies in this chapter were produced, as well as by the results reported from other projects associated with the ACIA, particularly the vulnerability approach described in Chapter 17. Further development of the collaborative model, from small projects to large research programs and extending from identifying research needs to designing response strategies, is an urgent need.

3.1. Introduction (Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic)

3.2. Indigenous knowledge

3.3. Indigenous observations of climate change

3.4. Case studies (Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic)

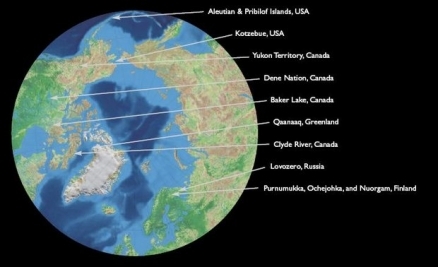

3.4.1. Northwest Alaska: the Qikiktagrugmiut3.5. Indigenous perspectives and resilience

3.4.2. The Aleutian and Pribilof Islands region, Alaska

3.4.3. Arctic Athabaskan Council: Yukon First Nations

3.4.4. Denendeh: the Dene Nation’s Denendeh Environmental Working Group

3.4.5. Nunavut

3.4.6. Qaanaaq, Greenland

3.4.7. Sapmi: the communities of Purnumukka, Ochejohka, and Nuorgam

3.4.8. Climate change and the Saami

3.4.9. Kola: the Saami community of Lovozero

3.6. Further research needs

3.7. Conclusions (Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Further research needs on Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Further_research_needs_on_Indigenous_Perspectives_on_the_Changing_Arctic- ↑ Riedlinger, D. and F. Berkes, 2001. Contributions of traditional knowledge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Record, 37(203):315–328;- Huntington, H.P. (ed.), 2000b. Impacts of Changes in Sea Ice and Other Environmental Parameters in the Arctic. Report of the Marine Mammal Commission workshop, Girdwood, Alaska, 15–17 February 2000. Marine Mammal Commission, Bethesda, Maryland, iv + 98p.

- ↑ Fox, S., 1998. Inuit Knowledge of Climate and Climate Change. M.A. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Canada;- Fox, S., 2002.These are things that are really happening: Inuit perspectives on the evidence and impacts of climate change in Nunavut. In:I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.).The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 12–53. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska;- Fox, S., 2004.When the Weather is Uggianaqtuq: Linking Inuit and Scientific Observations of Recent Environmental Change in Nunavut, Canada. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Colorado.- Furgal, C., D. Martin and P. Gosselin, 2002. Climate change and health in Nunavik and Labrador: lessons from Inuit knowledge. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 266–299. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska;- Jolly, D., F. Berkes, J. Castleden,T. Nichols and the Community of Sachs Harbour, 2002.We can’t predict the weather like we used to: Inuvialuit observations of climate change, Sachs Harbour,Western Canadian Arctic. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.).The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 92–125. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.- Jolly, D., S. Fox and N.Thorpe, 2003. Inuit and Inuvialuit knowledge of climate change. In: J. Oakes, R. Riewe, K.Wilde, A. Edmunds andA. Dubois, (eds.), pp. 280–290. Native Voices in Research. Aboriginal Issues Press.;- Nickels, S., C. Furgal, J. Castleden, P. Moss-Davies, M. Buell, B. Armstrong, D. Dillion and R. Fonger, 2002. Putting a human face onclimate change through community workshops: Inuit knowledge, partnerships, and research. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.).The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 300–333. Arctic Research Consortium ofthe U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.;- Thorpe, N., N. Hakongak, S. Eyegetok and the Kitikmeot Elders, 2001. Thunder on the tundra: Inuit qaujimajatuqangit of the Bathurst caribou. Generation Printing, xv + 208p.- Thorpe, N., S. Eyegetok, N. Hakongak and the Kitikmeot Elders, 2002. Nowadays it is not the same: Inuit qaujimajatuqangit, climate, and caribou in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, Canada. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.).The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 198–239. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ Mustonen,T., 2002. Snowchange 2002: indigenous views on climate change: a circumpolar perspective. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 350–356. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.

- ↑ N. Mymrin, Eskimo Society of Chukotka, Provideniya, Russia, pers. comm., 2002

- ↑ Huntington, H.P. and the communities of Buckland, Elim, Koyuk, Point Lay and Shaktoolik, 1999.Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the eastern Chukchi and northern Bering seas, Alaska. Arctic, 52(1):49–61.- Krupnik, I., 2002.Watching ice and weather our way: some lessons from Yupik observations of sea ice and weather on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. In: I. Krupnik, and D. Jolly (eds.).The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 156–197. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.;- Whiting, A., 2002. Documenting Qikiktagrugmiut knowledge of environmental change. Native Village of Kotzebue, Alaska.

- ↑ e.g.,Krupnik, I. and D. Jolly (eds.), 2002.The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska, xxvii + 356p.;- McDonald, M., L. Arragutainaq and Z. Novalinga, 1997.Voices from the Bay:Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the James Bay Bioregion. Canadian Arctic Resources Committee and Environmental Committee of the Municipality of Sanikiluaq, Ottawa, 90p.

- ↑ e.g., Brunner, R.D., A.H. Lynch, J. Pardikes, E.N. Cassano, L. Lestak and J.Vogel, 2004. An Arctic disaster and its policy implications. Arctic, 57(4):336–346.;- George, J.C., H.P. Huntington, K. Brewster, H. Eicken, D.W. Norton and R. Glenn, 2004. Observations on shorefast ice failures in Arctic Alaska and the responses of the Inupiat hunting community. Arctic, 57(4):363–374.

- ↑ Nickels et al., 2002, Op. cit.

- ↑ e.g., Stevenson, M.G., 1996. Indigenous knowledge and environmental assessment. Arctic, 49(3):278–291.

- ↑ e.g., Agrawal, A., 1995. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Development and Change, 26(3):413–439.

- ↑ e.g., Albert,T.F., 1988.The role of the North Slope Borough in Arctic environmental research. Arctic Research of the United States, 2:17–23.;- Fox, 2004, Op. cit.;- Huntington, H.P., 2000a. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5):1270–1274.;- Norton, D.W., 2002. Coastal sea ice watch: private confessions of a convert to indigenous knowledge. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp. 126–155. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., Fairbanks, Alaska.