Etosha Pan halophytics

ContentsWWF Terrestrial Ecoregions Collection |

The Etosha Pan Halophytics ecoregion is the relict landform of a prehistoric expansive, inland Pliocene lake. Today, the Etosha Pan is mostly an arid, saline desert. Typically, the intensively cracked, whitish clay is split into hexagonal salt-encrusted fragments, and wildlife is sustained only by scattered freshwater springs, which manifest as watering holes. These springs attract a diverse array of large mammals, especially during the dry season, making Etosha Pan a popular tourist destination. In unusually wet years, when the Ekuma, Oshigambo and Omuramba Ovambo Rivers receive sufficient rainfall, the pan is temporarily transformed into a shallow lake.

When surface water is present, it can be classified as a hypersaline lake, due to the elevated salinity. The Etosha Pan halophytics is considered within the Afrotropics Realm and is classified as part of the Flooded Grasslands and Savanna Biome.

Location and general description

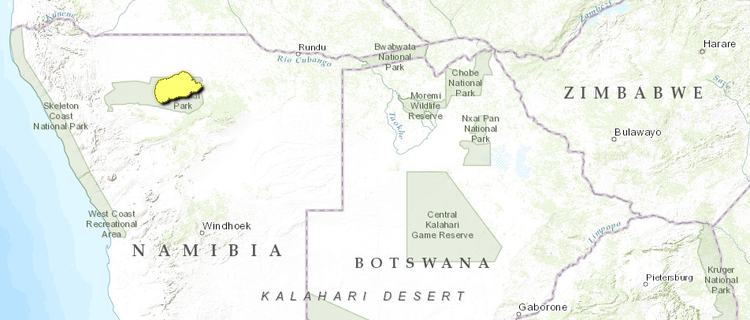

The Etosha Pan is situated within the Etosha National Park in northern Namibia around 16 °E longitude and 19 °S latitude. The pan is situated on the interior plain of Ovamboland. Elevation ranges from 1071 metres (m) to 1086 m above mean sea level. It is the largest pan system in Namibia and topographically consists of a generally flat, saline depression that is roughly 129 kilometres (km) from east to west and 72 km from north to south (6133 km2 in total). Smaller pans, such as Fisher’s Pan to the east and the Natukanaoka and Okahakana Pans to the west, flank the principal pan.

Meteorology and hydrology

Meteorology of the Etosha Pan is one of extremes in seasonal change. The mean annual rainfall of the Etosha National Park is about 430 millimetres (mm), varying from 419 mm at Okaukuejo, which lies on the western edge of the pan to 440 mm at Namutoni Fort, situated on the eastern edge. Most of the rain falls in late summer, January through April, with February having the mean maximum rainfall (110 mm). There are major fluctuations from one year to another. In 1946, for example, the rainfall was 90 mm, but in 1950 it was 975 mm. Climatically there are normally three distinct seasons; hot and wet (January to April), cool and dry (May to August), and hot and dry (September to December). The mean maximum monthly temperature is 33 °C for summer and 28 °C in winter. The mean minimum temperature for summer is 17 °C and winter 7 °C. Peak temperatures, higher than 40 °C, are frequent in the hot season and 0 °C is the lowest temperature recorded. High velocity winds are common during the late winter. During this period, visibility on the pan can be restricted by the high dust content of the atmosphere.

The pan is subject to periodic, partial flooding during the rainy season. Direct rainfall accounts for only a small proportion of the pan’s water; three rivers supply the majority: the Ekuma, Oshigambo, and Omuramba Ovambo. The Ekuma River flows seasonally from the southern shores of Lake Oponono, situated about 70 km north of the pan. This lake receives input from numerous perennial watercourses and oshanas (linearly-linked, shallow, parallel lakes), the Cuvelai River being the most important. The Oshigambo River draws its water from southern Angola. The Ekuma and Oshigambo Rivers form deltas in the northwestern corner of the pan, about 13 km apart. The Omuamba Ovambo River receives its water from a catchment to the northeast of Etosha, and it flows into the pan through Fisher’s Pan, a small eastern extension of the main pan body. All three rivers flow erratically during the rainy season and, depending on their levels, flood the pan to varying degrees. In unusually dry years, the rivers may not flow at all, forming a series of disconnected pools. During these dry years, the pan holds direct rainfall only. The pan does, however, usually hold some water for a few months between January and April. Once in about 7-10 years, during exceptional rains, the oshonas and rivers fill with rainwater and sometimes with floodwater from the perennial Cuvelai River in Angola. This water reaches the pan, transforming it into a shallow lake holding large sheets of water, usually not exceeding one meter in depth. The water in the pan is, however, unfit for animal consumption as the salt content is often double that of seawater.

Most of the time, however, the pan is a dry, salinedesert, and water is found only in numerous waterholes surrounding the pan. These waterholes are fed by springs, of which there are three different types: contact, water-level and artisan. Contact springs are the most common and are found at the edge of the pan where water-bearing calcrete comes to an end and water flows out onto the surface because the underlying layers of clay are impermeable. Okerfontein, to the southeast of the pan, is a good example of a contact spring. Water-level springs are depressions, which cut below the water table, exposing water. These are dependent on the water table and hence are unreliable in terms of water supply. Artesian springs are formed when pressure from overlying rocks forces water to the surface from deeper lying aquifers. These springs are reliable and include Namutoni in the east and Aus to the south of the pan.

In Pliocene times, the Kunene River flowed into a large inland lake, of which Etosha Pan is a present-day remnant. Continental uplift changed the course of the river towards Ruacana Falls in the west, cutting off the lake’s water supply. During the drying process, the soil of the pan became mineral-rich and brackish. Wind erosion deepened the depression over millions of years. Today the pan’s surface is a flat floor of saline sandy-clay that is poorly drained, allowing for easy waterlogging. When dry, the whitish clay cracks into hexagonal salt-encrusted fragments. The pH is high (8.8 to 10.2), and the sodium content is in excess of 30,000 parts per million (ppm). Away from the pan, the soils are shallow, brackish and alkaline and are associated with calcrete.

Vegetation

The Etosha Pan is almost devoid of Macrophytic vegetation and is classified as a saline desert. The dominant plants are a thin layer of blue-green algae that cover the surface of the pan during the rainy season. Only a few macrophytes are found here, the major species being Sporobolus salsus. This halophytic (salt-loving) species colonizes extensive areas of the pan and offers excellent grazing to herds of springbok, gemsbok and wildebeest during the dry season. The pan has a fringe of halophytic vegetation consisting principally of Sporobolus spicatus, Odyssea paucinervis, and the small shrub Suaeda articulata. S. articulata is common in the brackish, low-lying areas fringing the pan and is also found clinging to hummocks on the pan itself. Atriplex vestita, Sporobolus tenellus, and S. virginicus are also present as are the occasional patches of annuals such as Chloris virgata, Diplachne fusca, Dactyloctenium aegyptium, and Eragrostis porosa. Sporobolus spicatus and Odyssea paucinervis show a Cyclical succession, replacing each other as the pan is successively flooded or dries out.

When the pan dries out, a crust of saline soil is left on the surface but moist mud remains below the surface. This newly exposed surface is colonized by S. spicatus, which spreads rapidly by runners and produces a perennial sward. This persists during the most prolonged dry periods. O. paucinervis occurs with S. spicatus, but its tufts do not spread when the ground is dry. When the water rises, however, O. paucinervis colonizes vast areas of the pan that are shallowly flooded with warm water in which the salt crust is dissolved. Under these conditions, the S. spicatus mat rots away and O. paucinervis replaces it. On the wider fringes the vegetation changes to dwarf shrub savanna, composed mainly of the waterthorn Acacia nebrownii, which forms thick stands in places. Monechma tonsum, M. genistifolium, Leucospaera bainesii, Petalidium engleranum, Salsola tuberculata, and the mopane aloe (Aloe littoralis) are also present, covering wide areas around the pan, particularly where the soil is brackish.

Open grasslands rise gradually away from the pan and sustain a wide variety of perennial and annual grasses, most of which fall into the sweetveld category. These provide grazing for a large number of herbivores. The common grass species are Cynodon dactylon, Eragrostis micrantha, E. rotifer, Diplachne fusca, and Chloris virgata. The grasslands extend to the north of the pan where they are known as the Adoni flats. To the south and west of the pan Colophospermum mopane is the dominant tree species. To the east, sandveld vegetation encroaches, and it is here that bigger and more varied tree species, such as Terminalia prunoides, Lonchocarpus nelsii, and tamboti (Spirostachys africana) may be seen together with the mopane. The attractive makalani palm (Hyphaene ventricosa) is found all around the pan, particularly in the west, often forming clumps around the waterholes.

Biodiversity features

The harsh climate of the pan makes it an unsuitable habitat for most animals. Vegetation is scarce, and water, when present, is salty. Temperatures are extreme, and winds are fierce. Present are only highly specialized species, some of which are extremophiles that have adapted to withstand long dry periods and to respond rapidly to rainfall. These are mainly crusteacea, which dominate this environment because of their short life cycles and desiccation-tolerant eggs. Many can hatch, grow and produce eggs within 24 hours. The only large animal that can subsist restricted to the pan itself is ostrich (Struthio camelus). These birds nest on the pan as it affords them protection from scavengers, such as black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas), which seldom venture onto the pan.

Mammals

Ground squirrels and the endemic Etosha agama (Agama etoshae) are found on the fringes. The Etosha agama is the only animal endemic to this ecoregion. It is a 14 centimetre (cm) long reptile that forages for beetles and termites in the sandy soil around the pan.

In contrast to the desolate pan, the waterholes at the fringes of the pan (particularly in the south) are the sites of spectacular congregations of large ungulates. Zebra (Equus burchelli), blue wildebeest (Connocheatus taurinus), and springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) are the most numerous ungulates at these waterholes. Other species include elephant (Loxodonta africana), giraffe (Giraffa camelopardus), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), gemsbok (Oryx gazella), eland (Taurotragus oryx), kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), steenbok (Raphicerus campestris), Damara dik dik (Madoqua kirki), and the black-faced impala (Aepyceros melampus petersi VU).

Predators, such as lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panthera pardus), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), and brown hyena (Hyaena brunnea) are found close to the game at the waterholes. However, cheetah numbers are very low, due to relatively high densities of lion and hyena, which species are adept at stealing the kill of cheetahs. Smaller predators found at the waterholes are black-backed jackal and bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis). These huge concentrations of game are found during the dry winter months and have made the Etosha National Park one of Africa’s most popular national parks. During the wet summer months, the wildlife moves away from the waterholes to utilize the lush grazing and Temporary pools, mainly to the west of the park.

Reptiles

This ecoregion boasts several reptilian species, including the Cape thick-toed gecko (Pachydactylus capensis). The near-endemic Etosha agama (Agama etoshae) is found on the pans here and in the near vicinity. The Dwarf rockhead agama (Agama aculeata), which is more widely distributed in Southern Africa is also present in the Etosha Pans. The Helmeted turtle (Pelomedusa subrufa), also present in other saline pans such as the East African halophytics, is found at Etosha. Sundevall's writhing skink (Mochlus sundevalli) is the sole skink found in the ecoregion. There are two snake species found in the Etosha Pans halophytics: the Stripebelly sand racer (Psammophis subtaeniatus) and the Namib sand snake (Psammophis namibensis).

Amphibians

There is only a sole species of amphibian found in the Etosha Pans halophytics, the Senegal running frog (Kassina senegalensis); this taxon is also found in some other southern and eastern Africa halophytic pans such as the East African halophytics.

Avifauna

The Etosha National Park has a rich bird fauna, with more than 320 species recorded to date. The largest numbers of birds are found between October and April, when the summer migrants are present. Most species are found at the waterholes and only ostriches are found on the pan itself. During exceptional rains however, and when the rivers to the northwest flow, the saline desert is transformed into a shallow lake where huge flocks of pelicans, flamingos and other waterbirds arrive to feed and breed. Flamingos (the greater and lesser flamingos, Phoenicopterus ruber and Phoeniconaias minor) breed sporadically at only two main sites in southern Africa: Botswana’s Makgadigadi Pans and the Etosha Pan. These specialized and conspicuous birds have undertaken only four major breeding attempts at the Etosha Pan in 40 years. When the pan dried up earlier than usual in June 1969, the lack of water forced the adult flamingos to depart, leaving flightless chicks to starve to death. A rescue operation caught 20,000 chicks and released them into Fisher’s Pan. This pan dried up prematurely two years later and the young birds marched 30 km north. The chicks were fed along the way by the adults flying to and from the water. In August, the chicks moved again to the last remaining water in the Ekuma Delta. Flamingo rescue operations were also launched in 1989 and 1994. At this low level of natural recruitment, the Etosha Pan flamingo population is not a viable one. When it is flooded, white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) also nest on the pan. These pelicans feed on the fish that have moved southwards into the Cuvelai – Etosha system with the floodwaters from Angola. As the waters dry up, the pelicans move further north to feed, first to the rivers that feed the pan and then to Lake Oponono, 70 km north of the pan.

Current ecological status

The Etosha Pan is completely protected within Etosha National Park. In addition, it is one of four wetlands in Namibia initially designated as a Ramsar Site (a wetland of international importance). It is the only Ramsar Site that is not a coastal wetland; the others being the Walvis Bay wetlands, Sandwich Harbor and the Orange River mouth.

Types and Severity of Threats

While the pan itself is well protected within Etosha National Park, the Cuvelai drainage system is essential to the ecology of the pan. This system falls outside of the protected area network. Any alteration of water flow within this system could have a devastating effect on the ecology of the pan. A major diversion of water flow would, for example, prevent the pan from flooding, and the huge flocks of flamingos and pelicans would lose their breeding ground.

Another major threat to the ecology of the Etosha Pan is the introduction of pesticides, herbicides and insecticides into the ecosystem. National campaigns to combat human and stock disease vectors and agricultural pests have had a negative impact on the aquatic invertebrate fauna of the Cuvelai system that feeds the Pan. The anti-malarial spraying campaigns in the Owambo area, north of the pan, annually applied 120,000 kilograms (kg) of five percent DDT to the walls of huts in the area. At least three chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides, of which DDT was the most prominent, were found in the eggs of the lesser flamingo, and similar contamination was found in white pelican eggs.

Flamingo and white pelican colonies are also under threat from human disturbance. Sightseeing parties and low-flying aircraft cause the birds to become apprehensive and even to desert their eggs and young. The white pelican population is also in direct competition with people for food. Pelicans require 10% of their body weight in fish every day. A pair of white pelicans and their young (two chicks), for example, would require about 420 kg of fish to breed successfully. If the Cuvelai drainage system (particularly Lake Oponono) continues to be over-exploited by people, the pelicans will not be able to meet these feeding requirements and their populations will decline.

Justification of ecoregion delineation

Fundamental factors delineating the Etosha Pan are the hypersaline soil chemistry and the seasonal flooding limits of the pan. The boundaries for this ecoregion are based on the extent of halophytic vegetation within the mapped area. Remoteness from other halophytic areas, and distinctive fauna were considered important factors for making Etosha a distinct ecoregion. The ecoregion is given the ecocode AT0902 by the World Wildlife Fund.

Further reading

- For a terser summary of this entry, see the WWF WildWorld profile of this ecoregion.

- Balfour, D. and S. Balfour. 1992. Etosha. Struik Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa. ISBN: 1868251357

- Berry, H.H. 1971. Flamingo breeding on the Etosha Pan, South West Africa, during 1971. Madoqua, 1(5):5-31.

- Berry, H.H. 1972. Flamingo breeding on the Etosha Pan, South West Africa, during 1971. Madoqua series, 1(5):5-31.

- Berry, H.H., H.P. Stark, and A.S. van Vuuren. 1973. White Pelicans Pelecanus onocrotalus breeding on the Etosha Pan, South West Africa, during 1971. Madoqua, 1(7):17-31.

- Berry, C. 1991. Trees and Shrubs of the Etosha National Park. Directorate of Nature Conservation, Windhoek, Namibia.

- Branch, B. 1988. Field Guide to the Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town. ISBN: 0883590239

- Curtis, B., K.S. Roberts, M. Griffin, S. Bethune, C.J. Hay, and H. Kolberg. 1998. Species richness and conservation of Namibian freshwater macro-invertebrates, fish and amphibians. Biodiversity and Conservation, 7:447-466.

- du Plessis, W. 1992. In situ conservation in Namibia: the role of national parks and nature reserves. Dintera, 23:132-141.

- Ebedes, H. 1976. Anthrax epizootics in Etosha National Park. Madoqua, 10(2):99-118.

- Giess, W. 1971. A preliminary vegetation map of South West Africa. Dintera, 4:1-114.

- Hails, A.J. 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland.

- Hall, T. 1994. Spectrum Guide to Namibia. Struik Publishers, Cape Town. ISBN: 1556506090

- Joubert, E. and P.K.N. Mostert. 1975. Distribution patterns and status of mammals in South West Africa. Madoqua, 9(1):8-22.

- Kok, D.J. 1987. Invertebrate inhabitants of temporary pans. African Wildlife, 41(5):239.

- Le Roux, C.J.G. 1980. Vegetation Classification and Related Studies in the Etosha National Park. D.Sc. (Agric) thesis, Dept. of Plant Production, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

- Mc Intyre, C. and S. Atkins. 1991. Guide to Namibia and Botswana. Chalfont, St. Peter, England. ISBN: 094698364X

- Nordenstam, B. 1970. Notes on the flora and vegetation of Etosha Pan, South West Africa. Dintera, 5:3-6.

- Olivier, W.and S.Olivier. 1999. African Adventurer’s Guide to Namibia. Southern Book Publishers, Rivonia, South Africa. ISBN: 1868728587

- Revilio, B.and A.Revilio. 1994. Namibia. New Holland Publishers, London, Cape Town, Sydney. ISBN: 1853683647

- Santcross, N., S. Ballard and G.Baker. 2001. Namibia handbook. 368 pages

- Wellington, J.E. 1938. The Kunene River and the Etosha plain. South African Geography Journal, 20:150.

- White, F. 1983. The vegetation of Africa, a descriptive memoir to accompany the UNESCO/AETFAT/UNSO Vegetation Map of Africa (3 Plates, Northwestern Africa, Northeastern Africa, and Southern Africa, 1:5,000,000). UNESCO, Paris. ISBN: 9231019554

| Disclaimer: This article contains certain information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |