Sacred places and biodiversity conservation

Contents

- 1 Sacred places, biodiversity, and conservation

- 2 Biodiversity and conservation

- 3 Sacred places

- 4 Sacred places and conservation

- 5 Sacred groves and biodiversity management

- 6 International conservation organizations

- 7 Alliance for religions and conservation

- 8 Secular and/or sacred protection

- 9 Future research

- 10 Anthropology’s role

- 11 Conclusion

- 12 Note

- 13 Further Reading

Sacred places, biodiversity, and conservation

Sacred places are a new frontier for interdisciplinary research on their own merits and for their relevance for biodiversity conservation. The religious or cultural designation of an area as sacred, especially those which are relatively natural, may either intentionally or coincidentally promote the conservation of its associated biodiversity. Such sacred places can complement national parks and other protected areas established by governments. Collaboration among religious, governmental, scientific, and/or conservation agencies may be desirable for the protection of sacred sites and landscapes.

Biodiversity and conservation

Biodiversity is the variety of life at all levels from the genetic through those of the population, species, community, ecosystem, biome, and biosphere. Since the 1980s, Edward O. Wilson and other biologists have advanced biodiversity as a powerful catalyst for environmental research, education, and action, with a profound sense of gravity and urgency regarding life on Earth as increasingly endangered. In 2005, the final report of the United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment warned that if current patterns of biodiversity loss continue to increase, then future generations of humanity may be at risk. It estimated that current species extinction rates may be a thousand times greater than normal in nature, and that 12% of bird species and 23% of mammalian species are threatened with extinction. Some evolutionary and ecological processes may also be endangered. Accordingly, the extinction crisis is one of the most critical challenges for the 21st century.

The various kinds of government sanctioned protected areas throughout the world, like national parks, nature reserves, wildlife refuges, and wilderness areas, are a major historical achievement and certainly necessary. However, they are insufficient for biodiversity conservation because they cover only a small portion of the planet and do not adequately sample the entire range of species, [[ecosystem]s], and [[biome]s]. Most of the world’s biodiversity lies outside these government protected areas. However, throughout the world various kinds of community-based protected areas have developed since ancient times in connection with a multitude of diverse cultural practices including sacred places in nature. Restrictions on access and use of such areas, and especially for sacred places in nature, may reduce or even eliminate human environmental impact and thereby help protect species in the area. Nevertheless, only in the last two decades has the potential of community-based land and resource management systems to conserve biodiversity begun to be recognized by anthropologists, biologists, conservationists, environmentalists, and others. The recognition of the actual or potential conservation role of sacred places in nature has been even slower and more recent.

Sacred places

Special sites or areas that have one or more attributes which distinguish them as somehow extraordinary, usually in a religious or spiritual sense, are called sacred places. They tend to evoke a feeling of some awesome, mysterious, and transcendent power that merits special reverence and treatment like the active volcano Kilauea on the island of Hawai`i. Individuals may experience a sacred place in different ways as a site of fascination, attraction, connectedness, danger, ordeal, healing, ritual, meaning, identity, revelation, and/or transformation.

A wide range of "natural" phenomena, not just places, are considered sacred by one or another culture or religion, including particular mountains, [[volcano]es], hills, caves, rocks, soils, waterfalls, springs, rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, swamps, trees, groves, forests, plants, animals, wind, clouds, rain, rainbows, and so on. There are also coastal and marine phenomena that are considered to be sacred such as parts of wetlands, mangrove forests, estuaries, lagoons, beaches, islands, sea arches, sea grass beds, coral reefs, and tides. Some places that are considered sacred are connected with solar, lunar, and/or stellar cycles. Furthermore, sacred places are tremendously diverse, not only among cultures, religions, and regions, but also even within a single one of these categories.

A particular sacred place or area can actually encompass various individual sites and phenomena as integral parts of the whole or a sacred landscape, such as waterfalls, springs, caves, and meadows on a mountain like Shasta in northern California. Sites can be connected by a river, legends or stories, the histories of individuals or groups, and/or a pilgrimage routes like the centuries old Way of Saint James to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Thus, certain sacred places have persisted for centuries or even millennia. Some annually attract thousands or even millions of pilgrims and other visitors. The visitation pressure can be problematic in many ways. In contrast, there are other sacred places where humans are excluded or access is strictly limited to a special class of individuals such as ritual specialists, healers, or elders.

Sacred places are complex phenomena that can be viewed usefully as varying along several continua ranging from natural (or biophysical) to anthropogenic (or socio-cultural); prehistoric to historic, recent, or newly created; secret or private to public; single culture (or religion) to multicultural (or multi religious); intrinsic to extrinsic in value; uncontested to contested; and protected to endangered. Particular sacred places variously reflect one pole or another of some combination of these continua.

Sacred places and conservation

Many sacred places in nature are associated with indigenous cultures. Although indigenes compose only about 15% of the human population, estimates range from 200-600 million persons depending on definitions and sources, they occupy a much larger percentage of the land in the world, perhaps up to half. Indigenous societies commonly use a wide variety of natural resources for their survival, economy, medicines, rituals, and other purposes. Historical, cultural, and spiritual aspects of the ecology of indigenous societies are grounded in the biodiversity, [[ecosystem]s], and landforms in their habitat. Thus, indigenes are most important to consider in exploring the relationships between sacred places, biodiversity, and conservation.

A particularly striking case is provided by a study from Bruce A. Byers and colleagues with the Shona people who live in the Zambezi Valley of northern Zimbabwe. The Shona consider trees, rivers, pools, mountains, and even whole mountain ranges to be sacred. Their concept of sacred (inoera) connotes something that is life sustaining and linked to rain and the fertility of the land. A sacred place (nzvimbo inoera) is where spirits are present. Associated with it are certain rules of access as well as behaviors that are not allowed (taboos). Moreover, Byers and colleagues discovered that deforestation is at least 50% lower in sacred forests than in their secular counterparts. Some 133 species of native plants occur in these sacred forests, whereas they are variously threatened, endangered, or extirpated elsewhere in Zimbabwe. These researchers conclude that strategies for biodiversity conservation that link culture and nature are more likely to be effective than those imposed from the top down by government and/or international agencies and that ignore the traditional beliefs, values, institutions, and practices of local societies.

The mountain of Sorte is another outstanding example of a sacred place that is relevant to biodiversity conservation. It reflects a combination of religious influences. Sorte is located in the Chivacoa district of the state of Yaracuy in central Venezuela. The area is called El Monumento Natural de Maria Lionza. Sorte is sacred because of its association with the historic personage of Maria Lionza. The related spirit cult is a creative mixture of African, Catholic, and indigenous religions. Sorte has a substantial religious history, extending back at least to the 18th century, although some aspects of the cult developed mainly in the last few decades.

Sorte is the site of religious pilgrimages, especially during periods when religious and state holidays coincide. Pilgrims engage in rituals of purification and healing, vigils, and other religious experiences. Some go into a trance through spirit possession. The main shrine where the spirit of Maria Lionza is believed to reside is at the top of the mountain near a lake. There are numerous sacred caves and springs as well as shrines throughout the forest along the mountain side.

Maria Lionza has been characterized variously as a goddess or spirit that, among other things, protects the forest on Sorte. In a survey of forests and deforestation in Venezuela during the early 1970s, Lawrence S. Hamilton noticed that by far the best preserved forest in central Venezuela was around Sorte. The extent of the forest was substantial, around 40,000 hectares.

The close interconnections of many sacred areas with cultural and biological diversity mean that, if any one of these three is threatened or endangered, then the others may be as well. Sacred sites are a subject for human rights and legal action as well as for basic and applied research.

Sacred groves and biodiversity management

Sacred groves are stands of trees or patches of forest that local communities conserve primarily because of their religious importance. These groves can also serve economic, medicinal, social, and cultural functions. Some plant species in sacred groves may provide emergency foods during periods of drought, crop failure, and famine. Also such sacred places can help protect watershed resources like springs, soil fertility and moisture, and ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling. A variety of factors promote the conservation of biodiversity in sacred groves like general or selective limits or prohibitions on the use of biotic species. Also information may be kept secret from outsiders such as about species of ritual, medicinal, or commercial value.

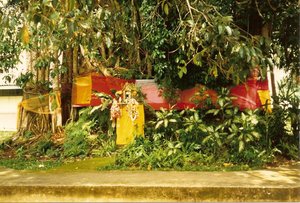

Sacred groves are dynamic systems, each with a historical ecology. A sacred grove may persist through centuries or more as a relict of a natural and/or anthropogenic ecosystem, be revived with the renewal of some cultural or religious traditions, or be newly established explicitly for the purpose of conservation. For example, sometimes as a resource management strategy a community will designate or sanctify a patch of forest to be a sacred grove, and then after a period of time desanctify it to use for other purposes. Also sacred groves are dynamic systems because the species composition of any plant community will naturally change over time with ecological succession, even without natural perturbations or human disturbances. Accordingly, a landscape can be a mosaic of patches of various types of plant communities, and that may help sustain some of the biodiversity in a region. Sacred groves can also serve as a seed source for an adjacent buffer zone and/or the ecological restoration of degraded landscapes. Indeed, often sacred groves, like other sacred places in nature, stand out as vegetation-rich ecosystems compared to their surroundings which are frequently degraded landscapes.

Sacred groves in India, for example, are traditionally associated with almost every village and temple. Today there are some 150,000 sacred groves covering 33,000 hectares in total, according to K.C. Malhotra. They range in size from a fraction of a hectare to a few square kilometers. While each sacred grove may be a relatively small island of biodiversity, they are numerous, and thus, collectively through space and cumulatively over time, they are of some environmental significance. In India and elsewhere sacred groves appear to be, in effect, a very ancient, widespread, and important traditional system of environmental conservation that long precedes more recent Western strategies for protected areas like wildlife sanctuaries and national parks.

International conservation organizations

Sacred groves and other traditional systems that have a conservation role, whether actual or potential and intentional or coincidental, may need to be strengthened or augmented by economic incentives for local communities; legal, government, and/or international environmental protection schemes; and the establishment and maintenance of buffer zones. Recognition and protection of sacred places by scientific, environmental, governmental, and/or non-governmental organizations can simultaneously promote their conservation as well as that of the associated biodiversity and cultures.

Among the international organizations at the vanguard of the recognition and protection of sacred places, many relevant for biodiversity conservation, are Conservation International with its Faith-Based Initiatives Program; Earth Island Institute through its Sacred Land Film Project; International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS); Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) and its World Network of Biosphere Reserves, a unit of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); Mountain Institute and its Sacred Mountains Project; Sacred Sites International; World Conservation Union (International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN)), formerly the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with its many different groups and their projects such as the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) and the Delos Initiative; World Heritage Centre and World Heritage Sites of UNESCO; and the World Wildlife Fund, now called World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). The latter has been collaborating with the Alliance for Religions and Conservation (ARC), and their work must suffice as an example here.

Alliance for religions and conservation

Established in 1995, ARC is a secular NGO that helps religious groups around the world to develop their own environmental programs drawing on their core beliefs, values, and practices. They have implemented over a hundred projects dealing with the protection of sacred localities.

The 2005 WWF/ARC report by Nigel Dudley and colleagues called Beyond Belief critically examines the possibilities of linking religious faiths with protected areas for the conservation of biodiversity. It provides background information, surveys 100 protected areas around the world, discusses in detail 14 case studies, and offers valuable cautions, recommendations, and guidelines. The project arose from a conference held in 2000 in Bangkok by the WWF and the WCPA. This meeting recognized that consideration of the economic, social, cultural, and religious aspects of environmental concerns is indispensable for effective biodiversity conservation.

Beyond Belief summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of sacred places for biodiversity conservation. The strengths are that they may be of high conservation value; more strongly protected and better managed than those that are solely government sanctioned and regulated; important for preserving traditional knowledge; significant manifestations of culture and cultural diversity; of intrinsic value because of their sacredness; and destinations for ecotourism. They may also attract increasing recognition, funding, and other support in contrast to secular places. The weaknesses are that the sacred place has not been adequately recognized and appreciated by the government and public; it may be semi-natural instead of pristine nature or wilderness; it may be too small or fragmented to possess much if any value for biodiversity conservation; it may be vulnerable to changes in the associated culture and religion; its economic values may be allowed to supercede religious ones; traditional custodians may wish to keep it secret; and knowledge and control of it may be reduced or removed from its traditional users. However, the authors point out that none of the above benefits and costs are inevitable, and that management is the most important factor influencing them. While protected area status for a sacred place is not always desirable and/or feasible, often it can be a mutually complementary arrangement for the interests involved.

Secular and/or sacred protection

Government protected areas, such as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, are viewed by many as an important historical change in land and resource values, attitudes, and uses as well as a major achievement for environmental and biodiversity conservation. Large areas are needed by big herbivores and carnivores that range widely in order to satisfy their needs. However, although government protected areas number over 100,000, they cover only about 10-15% of the world’s land surface and 1% of the ocean. Numerous species, [[ecosystem]s], and [[biome]s] are not adequately represented. Furthermore, protected areas that are not effectively administered on the ground can amount to little more than "paper parks."

While new protected areas continue to be implemented by governments and international organizations, more adequate coverage in terms of number, size, and sample of biodiversity can only be achieved by also embracing community based conservation, according to many experts. Local traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) together with sustainable resource use and management regimes can be of great practical importance in conservation, and these often involve sacred places in nature.

Future research

Systematic research is needed on the variety of sacred places with respect to biological matters such as their size, age, species composition, biodiversity level, and degree of naturalness as well as any historical, social, cultural, religious, economic, political, tenure, and legal matters. In particular, there is a need for controlled comparisons between sacred places and adjacent secular ones of the same size and type of biotic community in order to describe and assess any differences that might arise because of sacred status. Hypotheses about the conservation efficacy of sacred localities have to be tested empirically and quantitatively, rather than relying only on assumptions and assertions. However, in practice this may be difficult, impractical, or even impossible. Nevertheless, the relevance of many sacred places for biodiversity conservation is already strongly indicated by the accumulating work of numerous independent researchers and international organizations.

Anthropology’s role

As specialists who bridge the natural and social sciences, and sometimes even the humanities, ecological and environmental anthropologists are especially well positioned to help explore, document, and manage the connections among sacred places, cultures, religions, biodiversity, and conservation. A society’s view of nature and interaction with it are largely culturally constructed and mediated. This principle applies not only to communities with ideas about the sacredness or spirituality of particular localities in nature, but also to science and government with ideas like wilderness and biodiversity as illustrated by Ramachandra Guha, Max Oelschlaeger, Sahotra Sarkar, and David Takacs. In other words, there are different cultural meanings and approaches to conservation just as there are to nature. Anthropologists and others have demonstrated that Western science, technology, and government have no monopoly on environmental conservation.

When a purely Western scientific approach with its secular, materialist, and reductionistic worldview is applied to sacred places it may disrupt the associated culture and religion, generate resentment and conflict, and even lead to the degradation of the place, concerns repeatedly expressed in the proceedings of various UNESCO-MAB conferences on sacred places. Following cultural relativism as a methodological principle, anthropologists try to learn and understand other cultures and religions. Some also collaborate with members in promoting their practical concerns through applied or advocacy work, such as Christopher McLeod’s Sacred Land Film Project at the Earth Island Institute. In addition, anthropologists are especially well situated to serve as mediators among individuals from different interest groups like conservation, government, community, and religious organizations.

Anthropologists can bring to the attention of others the neglected potential as well as possible problems in pursuing sacred places for biodiversity conservation. For instance, Paige West, James Igoe, and Dan Brockington have elucidated from the perspective of political ecology the many negative impacts on local communities that may be precipitated through the development of protected areas by external agents if they act as eco-imperialists. However, community-based protected areas including sacred places can avoid most of these negative impacts. At the same time, it is important to avoid naively idealizing or romanticizing indigenous and other societies as always in perfect balance and harmony with nature. In any case, the fact that 50-100% of many protected areas are occupied in some way by people underlines the importance of anthropological considerations.

Numerous sacred places in nature are associated with indigenous societies. Because anthropology has traditionally focused on indigenous societies, and certainly they remain a core commitment of the profession, it has a unique role to play in this arena through basic and applied research as well as through advocacy and in promoting co-management schemes and empowerment, as Thomas Schaaf and others have demonstrated in their work with UNESCO-MAB. Protecting sacred places can simultaneously help protect cultures, religions, and rights as well as the associated biotic species and [[ecosystem]s].

Conclusion

Since the 1990s, sacred places have emerged as a new frontier for interdisciplinary research on their own merits and also for their actual or potential relevance for biodiversity conservation. This reflects the emerging recognition in many sectors of the important role that religion and spirituality can play in environmentalism. In some ways attention to these phenomena is a natural development. Even secular approaches to environmental protection often become a kind of sacralization of a space, such as pursuing wilderness as an ideal. This is exemplified by John Muir (1838-1914), who experienced the forested mountains of the Western United States as a sacred place, and who was especially influential in the creation of the national park system.

Many students of sacred places and related subjects are convinced that there is a dire need for a fundamental rethinking and reworking of contemporary spirituality, human ecology, environmentalism, and conservation as these are interconnected. They believe that the recognition and protection of sacred places in nature may be needed more than ever before for the survival of biodiversity and accordingly that of humankind in the 21st century. Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), a prominent pioneer in wildlife biology and conservation, stated most succinctly the essence of a viable ecocentric environmental ethic in his classic essay the “Land Ethic”: "A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." This ethic applies as well to sacred places and their role in biodiversity conservation.

Note

See the author's Environment in Focus feature, which includes a timeline, FAQs, supplemental reading, websites, and news stories related to sacred places and biodiversity conservation.

Further Reading

- Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC)

- Anderson, David G., and Eeva Berglund (Editors), 2003. Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN: 1571816968

- Anderson, E.N., 1996. Ecologies of the Heart: Emotion, Belief, and the Environment. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 0195090101

- Beltran, J. (Editor), 2000. Indigenous and Traditional Peoples and Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Case Studies. Gland: World Conservation Union/World Commission on Protected Areas/Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 4.

- Bernbaum, Edwin, 1992. Sacred Mountains of the World. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN: 0520214226

- Brandon, Katrina, Kent H. Redford, and Steven E. Sanderson, 1998. Parks in Peril: People, Politics, and Protected Areas. Washington, D.C.: The Nature Conservancy/Island Press. ISBN: 1559636084

- Brockman, Norbert C. (Editor), 1997. Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Brosius, J. Peter, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, and Charles Zerner (Editors), 2005. Communities and Conservation: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

- Bruner, Aaron G., Raymond E. Gullison, Richard E. Rice, and Gustavo A.B. da Fonesca, 2001 (Jan. 5). “Effectiveness of Parks in Protecting Tropical Biodiversity.” Science, n.s. 291(5501):125-128.

- Byers, Bruce A., Robert N. Cunliffe, and Andrew T. Hudak, 2001. "Linking the Conservation of Culture and Nature: A Case Study of Sacred Forests in Zimbabwe," Human Ecology, 29(2):187-218.

- Conservation and Society

- Conservation International, Faith-Based Initiatives Program

- Dove, Michael R., Percy E. Sajise, and Amity A. Doolittle, 2005, “Introduction: The Problem of Conserving Nature in Cultural Landscapes.” In: Conserving Nature in Culture: Case Studies from Southeast Asia, Dove, M.R.,P.E. Sajise, and A.A. Doolittle (Editors). New Haven: Yale Southeast Asian Studies Monograph 54, pp. 1-21.

- Dudley, Nigel, Liza Higgins-Zogib, and Stephanie Mansourian, eds., 2005. Beyond Belief: Linking Faiths and Protected Areas to Support Biodiversity Conservation. Gland: World Wide Fund for Nature/Manchester: Alliance of Religions and Conservation.

- Durning, Alan Thein, 1992. Guardians of the Land: Indigenous Peoples and the Health of the Earth. Washington, D.C.: Worldwatch Papers No. 112.

- Feinsinger, Peter, 2001. Designing Field Studies for Biodiversity Conservation. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Gaston, Kevin J., and John I. Spicer, 2004. Biodiversity: An Introduction. Malden: Blackwell Publishing (Second Edition).

- The George Wright Society

- Groombridge, Brian, and Martin D. Jenkins, 2002, World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth’s Living Resources in the 21st Century, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Guha, Ramachandra, 2000. Environmentalism: A Global History. Reading: Longman. ISBN: 0321011694

- Hadley, Malcolm, 2002. Biosphere Reserves: Special Places for People and Nature. Paris: UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme.

- Hamilton, Lawrence S. (Editor), 1993. Ethics, Religion and Biodiversity: Relations Between Conservation and Cultural Values. Cambridge: White Horse Press.

- Harmon, David, 2002. In Light of Our Differences: How Diversity in Nature and Culture Makes Us Human. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Harmon, David, and Allen Putney (Editors), 2003. The Full Value of Parks: From Economics to the Intangible. Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers.

- Heywood, V.H., (Executive Editor), 1995. Global Biodiversity Assessment. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Holm, Jean, and John Bowker (Editors), 1994. Sacred Place. London: Pinter.

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS)

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), 1997. Indigenous Peoples and Sustainability: Cases and Actions. Utrecht: International Books.

- Lee, Cathy, and Samanatha Wauchope, (Editors), 2003. The Importance of Sacred Natural Sites for Biodiversity Conservation (Proceedings of the International Workshop held in Kunming and Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve, People’s Republic of China, February 17-20, 2003). Paris: UNESCO-MAB Programme.

- Leopold, Aldo, 1966. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Levin, Simon Asher(Editor-in-Chief), 2001. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. San Diego: Academic Press, Volumes 1-5.

- Lockwood, Michael, Graeme Worboys, and Ashish Kothari(Editors), 2006. Managing Protected Areas: A Global Guide. Gland: IUCN/London:Earthscan.

- Maffi, Luisa (Editor), 2001. On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Malhotra, K.C., 1998. “Anthropological Dimensions of Sacred Groves in India: An Overview.” In: Conserving the Sacred for Biodiversity Management. Ramakrishnan, P.S., K.G. Saxena, and U.M. Chandrashekara (Editors). Enfield: Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 423-438.

- Mallarach, J.M. (Editor), 2007. Nature and Spirituality: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop of the IUCN WCPA Delos

- Initiative. Gland/Montserrat: IUCN/Publications Abbey of Montserrat.

- McLeod, Christopher, 2002. “In the Light of Reverence.” Sacred Land Film Project/Earth Island Institute.

- McNeely, Jeffrey A.(Editor), 1995. Expanding Partnerships in Conservation. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.

- Milton, Kay, 2002. Loving Nature: Towards an Ecology of Emotion. New York: Routledge.

- Minnis, Paul E., and Wayne J. Elisens (Editors), 2000. Native Americans and Biodiversity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- The Mountain Institute, Sacred Mountains Projec

- Nabokov, Peter, 2006. Where the Lightening Strikes: The Lives of American Indian Sacred Places. New York: Penguin.

- Oelschlaeger, Max, 1991, The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Orlove, Benjamin S., and Stephen B. Brush, 1996. "Anthropology and the Conservation of Biodiversity," Annual Review of Anthropology, 25:329-352.

- Posey, Darrell A.(Editor), 1998. Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity. London: Intermediate Technology Publications/ United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP).

- Ramakrishnan, P.S., K.G. Saxena, and U.M. Chandrashekara (Editors), 1998. Conserving the Sacred for Biodiversity Management. Enfield: Science Publishers, Inc.

- Russell, Diane, and Camilla Harshbarger, 2003. Groundwork for Community-Based Conservation. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

- Sacred Sites International Foundation

- Sarkar, Sahotra, 2005. Biodiversity and Environmental Philosophy: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sayre, Roger, Ellen Roca, Gina Sedaghatkish, Bruce Young, Shirley Keel, Roberto Roca, and Stuart Sheppard, 2000. Nature in Focus: Rapid Ecological Assessment. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Schaaf, Thomas, and Cathy Lee (Editors), 2006. Conserving Cultural and Biological Diversity: The Role of Sacred Natural Sites and Cultural Landscapes (Proceedings from the International Symposium on Conserving Cultural and Biological Diversity: The Role of Sacred Natural Sites and Cultural Landscapes, May 30-June 2, 2005, Aichi, Japan). Paris: UNESCO-MAB Programme.

- Shafer, Craig L., 1990. Nature Reserves: Island Theory and Conservation Practice. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Society for Conservation Biology, 2007. Catalog of Conservation Social Science Tools, Social Science Working Group.

- Sponsel, Leslie E., 2001. "Human Impact on Biodiversity: Overview.” In: Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Simon Asher Levin (Editor-in-Chief). San Diego: Academic Press, 3:395-409.

- Sponsel, Leslie E., Poranee Natadecha-Sponsel, Nukul Ruttanadakul, and Somporn Juntadach, 1997. "Sacred and/or Secular Approaches to Biodiversity Conservation in Thailand," Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion, 2(2):155-167.

- Srivastana, Sanjiv, Sudipto Chatterjee, Yogesh Gokhale, Kailash C. Malhotra, 2007. Sacred Groves of India: An Overview. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

- Stevens, Stan (Editor), 1997. Conservation Through Cultural Survival: Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Swan, James A., 1990. Sacred Places: How the Living Earth Seeks Our Friendship. Santa Fe: Bear and Company.

- Takacs, David, 1996. The Idea of Biodiversity: Philosophies of Paradise. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Taylor, Bron R.(Editor-in-Chief), 2005. The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. New York: Thoemmes Continuum.

- Terralingua: Partnership for Linguistic and Biological Diversity

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), World Conservation Monitoring Centre

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, and Wakayama Prefectural Government, 2001. Final Report of the UNESCO Thematic Expert Meeting on Asia-Pacific Sacred Mountains Meeting held in Wakayama City, Japan, September 5-10, 2001. Tokyo: UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Wells, M., and K. Brandon, 1992. People and Parks: Linking Protected Area Management with Local Communities. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, World Wildlife Fund.

- West, Paige, James Igoe, and Dan Brockington, 2006. “Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 35:251-277.

- Wilson, Edward O., 1984. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, Edward O., 1999, The Diversity of Life. New York: W.W. Norton and Company (Second Edition).

- World Conservation Union (IUCN), World Commission on Protected Areas

- World Resources Institute (WRI), The World Conservation Union (IUCN), and the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP),1992. Global Biodiversity Strategy: Guidelines for Action to Save, Study, and Use Earth’s Biotic Wealth Sustainably and Equitably. Washington, D.C.: WRI, IUCN, and UNEP.