Columbia River

The Columbia River is the largest North American watercourse by volume that discharges to the Pacific Ocean. With headwaters at Columbia Lake, in Canadian British Columbia, the course of the river has a length of approximately 2000 kilometers and a drainage basin that includes most of the land area of Washington, Oregon and Idaho as well as parts of four other U.S. states and two Canadian provinces.

Much of the higher elevation temperate coniferous forests within the Columbia Basin are ecologically intact; however, considerable destruction (Habitat destruction) of basin grasslands has occurred over the last two centuries via overgrazing and conversion to cropland. Sizable damage has been sustained in the Columbia River over the last two centuries due to massive amounts of chemical runoff from agricultural uses, and also due to construction of dams and locks altering the natural river hydrology. Moreover, hydroelectric power generated on the Columbia River exceeds that produced from any other North American river.

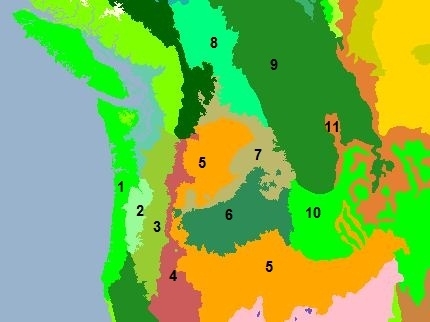

Map of the Columbia River watershed with the Columbia River highlighted. Source: Kmusser based on USGS and Digital Chart of the World data.

Contents

Climate

Precipitation is strongly seasonal, with most occurrences in the winter months. Precipitation and temperatures are also strongly spatially variant within the watershed due to elevation differences and the fact that much of the basin is quite arid, being in the rain-shadow of the Cascade Mountains.

Higher Columbia basin elevations manifest cold winters and short cool summers; however, interior portions of the basin are subject to considerable thermal variability and natural drought cycles. In some of the catchment area, particularly west of the Cascade Ranges, precipitation maxima occur in December through March, when Pacific Ocean generated storms arrive ashore. Atmospheric conditions block the flow of moisture in the months July through September, which is generally dry except for infrequent thunderstorms in the basin interior. In certain eastern parts of the basin, especially shrub-steppe ecosystems with patterns that are continental climate dominated, precipitation maxima occur in May and June. Annual precipitation varies from more than 250centimeters (cm) per annum in the Cascades to less than 20cm in the interior.

Basin hydrology

Snake River, with Grand Tetons in background, an eastern tributary basin of the Columbia River. @ C.Michael Hogan The Columbia River basin drains portions of the USA states of Washington, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Montana and Wyoming, as well as southern elements of the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta.

Snake River, with Grand Tetons in background, an eastern tributary basin of the Columbia River. @ C.Michael Hogan The Columbia River basin drains portions of the USA states of Washington, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Montana and Wyoming, as well as southern elements of the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta.

The catchment total drainage area approximates 675,000 square kilometers. This is North America's fourth largest river basin area after the Mississippi-Missouri, Mackenzie, and St. Lawrence rivers.

Headwaters of the mainstem of the Columbia River originate in Lake Columbia in the southern part of the Rocky Mountain Trench in British Columbia, Canada.

The largest tributary of the Columbia River is the 1735 kilometer long Snake River, whose drainage basin measures about 278,000 square kilometers.

Other major tributaries of the Columbia River are the Willamette River (30,000 square kilometer basin); the Kootenai River (50,000 square kilometer basin); and the Pend Orielle River (67,000 square kilometer basin).

The hydrology of the Columbia River basin has been profoundly altered by numerous large dams. There are over 250 reservoirs and around 150 hydroelectric projects in the basin, including 18 mainstem dams on the Columbia and its main tributary, the Snake River.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for the largest number of dams as shown in the figure below (shown as red dots.) The US Army Corps of Engineers operates nine of ten major federal projects on the Columbia and Snake rivers, and Dworshak Dam on the Clearwater River, Libby Dam on the Kootenai River, and Albeni Falls Dam on the Pend Oreille River. The federal projects are a major source of power in the region, and provide flood damage reduction, navigation, recreation, fish and wildlife, municipal and industrial water supply, and irrigation benefits. (Army Corps)

Water quality

Water quality has deteriorated over the last century, due to agricultural runoff and logging practices, as well as water diversions that tend to concentrate pollutants in the reduced water volume. For example nitrate levels in the Columbia generally tripled in the period from the mid 1960s to the mid 1980s, increasing from a typical level of one to three milligrams per liter. Considerable loading of herbicides and pesticides also has occurred over the last 70 years, chiefly due to agricultural land conversion and emphasis upon maximizing crop yields.

Heavy metal concentrations in sediment and in fish tissue had become an issue in the latter half of the twentieth century; however, considerable progress has been made beginning in the 1980s with implementation of provisions of the U.S.Clean Water Act, involving attention to smelter and paper mill discharges along the Columbia.

Aquatic biota

Bull trout, the largest benthopelagic fish in the Columbia River. Source: U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service The Columbia River Basin provides habitat for six species of anadromous salmon (chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, pink, and steelhead), shad, smelt and lamprey. Anadromous salmon hatch in fresh water rivers and tributaries where they rear for a year or two. They then migrate to and mature in the ocean, and return to their place of origin as adults to spawn. Salmon live two to five years in the ocean before returning to spawning areas.

Bull trout, the largest benthopelagic fish in the Columbia River. Source: U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service The Columbia River Basin provides habitat for six species of anadromous salmon (chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, pink, and steelhead), shad, smelt and lamprey. Anadromous salmon hatch in fresh water rivers and tributaries where they rear for a year or two. They then migrate to and mature in the ocean, and return to their place of origin as adults to spawn. Salmon live two to five years in the ocean before returning to spawning areas.

The largest freshwater fish found in the Columbia River is the demersal species white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) that can attain a body length of 610 centimeters (cm). The largest freshwater benthopelagic species occurring here is the bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus), which can attain a length of about 103 cm and is most often found at higher elevations of the basin. Other large demersal species occurring in the Columbia Basin are the 76 cm Pacific lamprey (Lampetra tridentata); the 55 cm Brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus); the 61 cm largescale sucker (Catostomus macrocheilus); the 64 cmlongnose sucker (Catostomus catostomus catostomus); and the 65 cm Utah sucker (Catostomus ardens). Other large benthopelagic fish in the Columbia are the 63 cm northern pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus oregonensis) and the 45 cmTui chub (Gila bicolor).

Salmon runs in the Columbia mainstem in prehistoric times are thought to have realized numbers in the ten to fifteen million fish per annum; in the Snake River, salmon numbers amounted to 1,500,000 in prehistory. Due to water pollution and dam construction, these steelhead, coho and chinook numbers have declined substantially by 2012.

Terrestrial ecosystems

|

1. Central Pacific coastal forests 3. Central and Southern Cascades forests 5. Snake-Columbia scrub steppe 9. North Central Rockies forests |

|

Columbia River Gorge with conifer forested fringes. There are eleven ecoregions that comprise the Columbia River drainage basin. At the mouth of the Columbia is found the [[Central Pacific coastal forests] ecoregion], which occupies approximately the last 100 kilometers of the Columbia's course, but only a very small fraction of the actual drainage basin. The Central and Southern Cascades forests occupy generally higher elevation areas further upriver. The arid [[Palouse grasslands] ecoregion] lies yet further upriver in the rainshadow of the Cascade Ranges. Yet further upbasin in the Columbia River watershed lie the North Central Rockies forests.

Columbia River Gorge with conifer forested fringes. There are eleven ecoregions that comprise the Columbia River drainage basin. At the mouth of the Columbia is found the [[Central Pacific coastal forests] ecoregion], which occupies approximately the last 100 kilometers of the Columbia's course, but only a very small fraction of the actual drainage basin. The Central and Southern Cascades forests occupy generally higher elevation areas further upriver. The arid [[Palouse grasslands] ecoregion] lies yet further upriver in the rainshadow of the Cascade Ranges. Yet further upbasin in the Columbia River watershed lie the North Central Rockies forests.

Central Pacific coastal forests

The Central Pacific coastal forests are among the most biologically productive on Earth, characterized by substantial trees, large volumes of woody debris, luxuriant growth of mosses and lichens, along with abundant ferns and herbs on the forest floor. The principal forest complex consists of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), encompassing seral forests dominated by Douglas-fir and massive old-growth forests of fir, hemlock, western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and other species. These forests occur from sea level up to elevations of 700 to 1000 meters (m) in the Coast Range and Olympic Mountains. This forest type occupies a wide range of environments with variable composition and structure and includes such other species as grand fir (Abies grandis), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), and western white pine (Pinus monticola).

Central and Southern Cascades forests

The Central and Southern Cascades forestsspan several physiographic provinces in Washington and Oregon, including the Southern, Western and High Cascades. This ecoregion extends from Snoqualmie Pass in Washington to immediately north of the California border. The region is characterized by accordant ridge crests separated by steep, deeply dissected valleys, strongly influenced by historic and recent volcanic events. Ridge elevations in the northern section are as high as 2000 meters (m) with three dormant volcanoes ranging from 2550 m (Mount Saint Helens) to 4392 m (Mount Rainer). The stratigraphy dates to Precambrian-Cenozoic epochs. Pleistocene glacial activity has been widespread, creating numerous lakes and mountain valleys.

Palouse grasslands

The Palouse grasslands have been mostly destroyed (Habitat destruction) and degraded by overgrazing and by historic [[agricultural] land] conversion. The Palouse historically resembled the mixed-grass vegetation of the central grasslands, except for the absence of short grasses. Such species as Agropyron spicatum, Festuca idahoensis, and Elymus condensatus, and the associated species Poa scabrella, Koeleria cristata, Elymus sitanion, Stipa comata, and Agropyron smithii originally dominated the Palouse prairie grassland.

North Central Rockies forests

The North Central Rockies forests have a number of notablepopulations of large carnivores, including wolves (Canis lupus), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), and wolverines (Gulo luscus). There are also populations of rare woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus ssp. caribou), the only caribou to live in areas of deep snow. Other wildlife include: black bear (Ursus americanus), mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), grouse (Dendragapus spp.), waterfowl, black and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus and O. virginianus), and moose (Alces alces). In the southeast, marten (Martes ameriana) and bobcat (Lynx rufus) occur.

South Central Rockies forests

The South Central Rockies forests have considerable intact habitat units including much of Yellowstone National Park, Grand Tetons, Frank Church Wilderness, central Idaho; Lemhi and Lost River Ranges, eastern Idaho; the Beaverhead, southwestern Montana;Anaconda-Pintler, southwestern Montana; Pioneer, southwestern Montana; Tobacco Root, southwestern Montana; Snowcrest, southwestern Montana; Centennial, southwestern Montana; and the Madison Ranges, southwestern Montana.

Prehistory

Native Americans arrived to the Columbia River basin approximately 15,000 to 12,000 years before present, with one of the earliest carefully excavated sites being the Marmes Rockshelter in the Snake River sub-basin. Marmes is radiocarbon dated to at least 11,230 years before present, and contains rich finds of early chalcedony and chert arrowpoints, revealing the hunter-gatherer nature of this society. the Marmes site is situated near the confluence of the Snake and Palouse Rivers in the state of Washington.

History

The earliest recorded European discovery of the Columbia River was in the year 1775 by navigator Bruno de Hecata, who was in search of the fabled mythical Northwest Passage. Hecata merely sighted the Columbia's mouth from the Pacific Ocean, but was daunted by the strong current from entering the river itself. American captain John Gray became the first navigator to record an entrance into the Columbia River mouth, voyaging upriver approximately 21 kilometers in 1792 to a point where the eponymous Grays River enters the Columbia from the north; later the same year British explorer William Broughton sailed 160 kilometers upriver from the Columbia mouth.

American legendary explorers William Clark and Meriwether Lewis explored the uncharted northwest territory in their famed expedition of 1803 to 1805. After traversing the Rockies, their journey put an end to the notion of a Northwest Passage anywhere in the Pacific Northwest. These explorers constructeddugout canoes and navigated downstream on the Snake River, entering the Columbia mainstem near what is the present day Tri-Cities urban area.

References

- Ellen Morris Bishop, 2003. In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN978-0-88192-7894

- Derek Hayes. 1999. Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of Exploration and Discovery. Seattle, Washington: Sasquatch Books . ISBN1-57061-2153.

- R.A.Kimbrough, G.P.Ruppert, W.D.Wiggins, R.R.Smith, D.L.Kresch. 2006. Water Data Report WA-05-1: Klickitat and White Salmon River Basins and the Columbia River from Kennewick to Bonneville Dam. Water Resources Data: Washington Water Year 2005. United States Geological Survey

- Richard Kiy. 1998. Environmental management on North America's borders (Google eBook) Texas A&M University Press. 306 pages

- D.W.Meinig. 1995. The Great Columbia Plain. University of Washington Press. ISBN0295-97485-0.

- National Research Council (U.S.). 2004. Managing the Columbia River: instream flows, water withdrawals, and salmon survival (Google eBook) Committee on Water Resources Management, Instream Flows, and Salmon Survival in the Columbia River Basin. Water Science and Technology Board, National Research Council (U.S.). Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, National Research Council (U.S.). Division on Earth and Life Studies National Academies Press. 246 pages

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2002. Columbia River Fish Runs and Fisheries.

- James P.Ronda. 1984. Lewis and Clark among the Indians. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 08032-8990-1.

- John C. Sheppard; Peter E. Wigand; Carl E. Gustafson; Meyer Rubin. 1987, A Reevaluation of the Marmes Rockshelter Radiocarbon Chronology. American Antiquity, Vol. 52, No. 1. pp. 118-125.

- World Wildlife Fund. 2010. Western North America Ecoregions.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Columbia River Basin - Dams and Salmon