Central and Southern Cascades forests

ContentsWWF Terrestrial Ecoregions Collection |

==

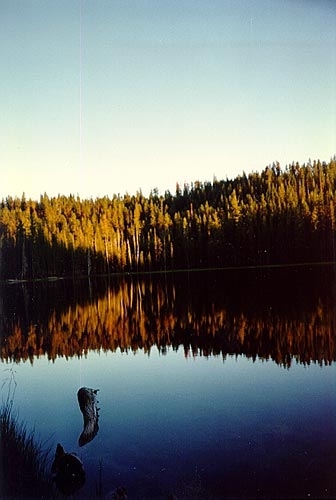

The Central and Southern Cascades forests span several physiographic provinces in Washington and Oregon, including the southern Cascades, the Western Cascades, and the High Cascades, all within the USA. This ecoregion extends from Snoqualmie Pass in Washington to slightly north of the California border. The region is characterized by accordant ridge crests separated by steep, deeply dissected valleys, strongly influenced by historic and recent volcanic events (e.g. Mount Saint Helens). Ridge elevations in the northern section are as high as 2000 meters (m) with three dormant volcanoes ranging from 2550 m (Mount Saint Helens) to 4392 m (Mount Rainier). The stratigraphy dates to Precambrian-Cenozoic epochs. Pleistocene glacial activity has been widespread, creating numerous lakes and mountain valleys. However, most glaciers were restricted to small alpine areas. The Central and Southern Cascades forests is part of the Nearctic Realm, and an element of the Temperate Coniferous Forests biome.

The region is characterized by numerous perennial streams and lakes maintained by abundant annual precipitation (1270 to 3048 millimeters). Soils are generally andisols and spodsols; however, soil series vary considerably across the region in association with local climatic differences and edaphic processes. Potential vegetation includes the western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis), and western red cedar series (Thuja plicata). Predominant natural disturbances include fire, wind, floods, and volcanoes. Extensive logging and fire suppression have substantially altered natural disturbance regimes, shifting regional landscapes from those with a full range of seral stages to highly fragmented landscapes where late-seral stages are rapidly being replaced by monocultural tree plantations.

Biological distinctiveness

Compared to other [[ecoregion]s] within the Temperate Coniferous Forest Major Habitat Type, this ecoregion contains intermediate levels of faunal biodiversity (e.g., total species richness = 493). The World Wildlife Fund classifies vertebrate species to number 333. Birds represent the majority (41%) of faunal taxa evaluated, followed by butterflies (26%), and mammals (13%). This ecoregion contains one of the highest levels of endemic amphibians (five of eleven ecoregion endemics are amphibians) of any ecoregion within its major habitat type. Several taxa, including salamanders (e.g., Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus) and Ensatina spp.); frogs, e.g. Tailed frog (Ascaphus truei)); fishes, e.g. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus); and birds, e.g. Northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), Northern goshawk Accipiter gentilis) have been the focus of conservation attention in this ecoregion, because of their close association with declining habitat types such as aquatic areas, seeps, talus slopes, old growth, and riparian forests. The threatened Northern spotted owl has been used as an indicator species in environmental impact assessments, since its range overlaps with 39 listed or proposed species (ten of which are late-seral associates) and 1116 total species associated with late-seral forests. Late-seral forests in general are of national and global importance because they provide some of the last refugia for dependent species, and perform vital ecological services, including sequestration of carbon, cleansing of atmospheric pollutants, and maintenance of hydrological regimes.

At finer mapping scales, the USDA Forest Service and USA Bureau of Land Management have identified two hot biodiversity spots within the Southern Cascades and Upper Klamath Ecological Reporting Units (overlaps with this ecoregion). These areas contain unusually high levels of species richness for diverse taxa (e.g. invertebrates, bryophytes, lichens, fungi, vascular plants, and vertebrates) relative to other ecological reporting areas within the Columbia River Basin. One of the two hot-spots also received a relatively high composite ecological integrity ranking, meaning that the area still consists of a mosaic of plant and animal communities maintained by ecologically well-connected, high-quality [[habitat]s].

Mammals

There are a large number of mammalian taxa in the ecoregion, including: Bobcat (Lynx rufus); Wolverine (Gulo gulo); California ground squirrel (Spermophilus beecheyi); Yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris); Ermine (Mustela erminea); Fog shrew (Sorex sonomae), an endemic mammal to the far western USA; Hoary marmot (Marmota caligata); Mountain beaver (Aplodontia rufa); and the Near Threatened red tree vole (Arborimus longicaudus); Yellow pine chipmunk (Tamias amoenus); and the American water shrew (Sorex palustris).

Amphibians

Olympic torrent salamander. Source: Todd Pierson/EoL There are a number ofl amphibian taxa present in the Central and Southern Cascades ecoregion; the totality of these species are: the Rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa); the endemic and Vulnerable Shasta salamander (Hydromantes shastae); the endemic and Vulnerable Oregon slender salamander (Batrachoseps wrighti); the Endangered Dunn's salamander (Bolitoglossa dunni); the Northwestern salamander (Ambystoma gracile); the Near Threatened western toad (Anaxyrus boreas); the Vulnerable Oregon spotted frog (Rana pretiosa); the Near Threatened Cascades frog (Rana cascadae); Coastal tailed frog (Ascaphus truei); Near Threatened Larch Mountain salamander (Plethodon larselli); California newt (Taricha torosa); Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus); Cope's giant salamander (Dicamptodon copei); Monterey ensatina (Ensatina eschscholtzii); the Near Threatened Foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii); Northern Red-legged frog (Rana aurora); Pacific chorus frog (Pseudacris regilla); Van Dyke's salamander (Plethodon vandykei), an endemic of the State of Washington, USA; Long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum); and the Olympic torrent salamander (Rhyacotriton olympicus).

Olympic torrent salamander. Source: Todd Pierson/EoL There are a number ofl amphibian taxa present in the Central and Southern Cascades ecoregion; the totality of these species are: the Rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa); the endemic and Vulnerable Shasta salamander (Hydromantes shastae); the endemic and Vulnerable Oregon slender salamander (Batrachoseps wrighti); the Endangered Dunn's salamander (Bolitoglossa dunni); the Northwestern salamander (Ambystoma gracile); the Near Threatened western toad (Anaxyrus boreas); the Vulnerable Oregon spotted frog (Rana pretiosa); the Near Threatened Cascades frog (Rana cascadae); Coastal tailed frog (Ascaphus truei); Near Threatened Larch Mountain salamander (Plethodon larselli); California newt (Taricha torosa); Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus); Cope's giant salamander (Dicamptodon copei); Monterey ensatina (Ensatina eschscholtzii); the Near Threatened Foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii); Northern Red-legged frog (Rana aurora); Pacific chorus frog (Pseudacris regilla); Van Dyke's salamander (Plethodon vandykei), an endemic of the State of Washington, USA; Long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum); and the Olympic torrent salamander (Rhyacotriton olympicus).

Reptiles

There are a moderate number of reptilian species present in the ecoregion, namely in total they are: Western pond turtle (Emys marmorata); Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis); Sharp-tailed snake (Contia tenuis); Ringed-neck snake (Diadophis punctatus); Rubber boa (Charina bottae); California mountain kingsnake (Lampropeltis zonata); Yellow-bellied racer (Coluber constrictor); Western rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis); Western gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer); Common garter snake (Thanophis sirtalis); Northwestern garter snake (Thamnophis ordinoides); Western skink (Megascops kennicottii); Southern alligator lizard (Elgaria multicarinata); and the Northern alligator lizard (Elgaria coerulea).

Birdlife

There are a considerable number of avifauna within the Central and Southern Cascades ecoregion; representative species are: Flammulated owl (Otus flammeolus); Western screech owl (Megascops kennicottii); White-tailed ptarmigan (Picoides albolarvatus); and White-headed woodpecker (Picoides albolarvatus).

Conservation status

Habitat loss and degradation

Habitat loss within late-seral forests and aquatic areas have been extensive throughout this ecoregion. In particular, late-seral multi- and single-story forestcos have declined basin-wide to as much as 40 percent of their original extent. Late-seral forests in general have experienced sharp declines in many other ecoregions within the temperate coniferous forest major habitat type and are therefore a national as well as ecoregional priority. In addition, mid-seral subalpine forests have experienced a 35 percent decrease while late-seral montane multi-story forests have increased by 35 percent. Moreover, many terrestrial and aquatic areas within this ecoregion have relatively low composite ecological integrity rankings due primarily to cumulative impacts of extensive logging, road building, and hydroelectric development. Declines in salmonid populations have been severe throughout the ecoregion and basin-wide; however, a few aquatic strongholds and areas of very low road densities still persist within the ecoregion.

In addition to the above declines, ecological processes in this region have been altered by a century of fire suppression activities that have increased the severity and extent of fires and altered fire-dependent plant communities. The absence of periodic fires also has resulted in declines in rangeland integrity and increases in exotic species (Alien species) invasions.

Remaining blocks of intact habitat

Both the Oregon and Washington GAP projects provide more detailed information on remaining intact blocks of habitat and areas of high biological importance outside protected areas. In addition, the USDA Forest Service and USA Bureau of Land Management identified other key areas of importance to fish and terrestrial biodiversity, particularly the aquatic strongholds and biodiversity hot-spots discussed above. The workshop participants provided the following local knowledge of relatively intact habitats that should be added to these sources:

- Mount Rainier National Park, central Washington - 947 square kilometers (km2)

- Three Sisters Wilderness Area, central Oregon - 1107 km2

- Crater Lake National Park, south-central Oregon - 614 km2

- Sky Lakes Wilderness Area, south-central Oregon - 453 km2

- Mount Jefferson Wilderness Areas, central Oregon - 427 km2

- Goat Rocks Wilderness Area, south-central Washington - 355 km2

- Aquatic diversity areas and late-seral owl reserves in each National Forest in the ecoregion

Degree of fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation has been extensive throughout this ecoregion, as indicated by the few remaining intact late-seral forests, high road densities, and low ecological integrity rankings discussed above.

Degree of protection

Protected sites in this ecoregion primarily include the remaining intact habitat blocks identified above. In addition, several late-seral forest reserves have been administratively protected under the Northwest Forest Plan for forests within the range of the northern spotted owl. However, many of these administratively protected areas as well as the aquatic diversity areas remain vulnerable to federally mandated salvage logging under the timber salvage rider.

Ecological Threats

Logging is the primary threat to biodiversity in this region. Over aggressive fire suppression, exotic species (Alien species) invasions, and road building have caused extensive damage to key watersheds, late-seral forests, and rangelands in this ecoregion.

Suite of priority activities to enhance biodiversity

- Restore forest and aquatic integrity to the region by protecting all remaining late-seral forests, native grassland/shrub communities, aquatic strongholds, roadless areas, and biodiversity hot-spots. These areas provide building blocks and source pools for colonization into degraded landscapes. The preferred alternative recently released for the Columbia River Basin Environmental Impact Statement failed to provide adequate protection for these areas and instead proposes aggressive restoration for most of the basin, despite the recommendations of conservationists for a comprehensive restoration plan that includes a network of core reserves, buffers, landscape connectivity, and restoration areas.

- Reintroduce fire through prescribed fire management both in fire-dependent rangelands and forests.

- Integrate biodiversity conservation objectives with more sustainable and diversified regional economies. This ecoregion as well as many other places in the Columbia River Basin are experiencing a shift in human demographics and jobs from single-resource dependency to more diversified economies. Basin-wide lumber and wood products production, for instance, represent only 2.5 percent of the basin employment while recreation represents 15 percent. In addition, timber harvest in the basin currently accounts for ten percent of the U.S. harvest, down from 17 percent since 1986, and it is thought to have declined to five percent at the year 2000. In particular, this ecoregion was given a relatively high socioeconomic resiliency ranking, meaning (in part) that it is not as dependent on any one resource or job sector as other places within the basin. Thus, the opportunities are thought to be high in this ecoregion to integrate conservation with sustainable economies.

Conservation partners

- Audubon Society

- Inland Empire Public Lands Council

- Klamath Forest Alliance

- National Wildlife Federation, Western Division

- Northwest Ecosystem Alliance

- Pacific Rivers Council

- Selkirk-Priest Basin Association

- Key individuals active in this region and ecoregions 29, 34, and 35 include Dr. James Karr (University Washington), Dr. Bill Romme (Fort Lewis College, Colorado), and Dr. Dave Perry (Oregon State University).

Relationship to Other Classification Schemes

This ecoregion corresponds to Omernik's Level III Ecoregion 4 (Cascades). There is high concordance in the centroids of this ecoregion when compared to McNab and Bailey's classification. However, their delineation of this ecoregion continues further north, encompassing the entire Cascade Mountain range within the U.S.. In addition, this ecoregiton overlaps with three physiographic provinces identified by Franklin and Dyrness, including the Southern, Western and High Cascades. The Central and Southern Cascades ecoregion is given the ecocode NA0508 by the World Wildlife Fund.

Neighboring ecoregions

The following ecoregions have some form of tangency to the Central and Southern Cascades ecoregion:

- Klamath-Siskiyou forests, at the southwest

- Willamette Valley forests, to the west

- Puget lowland forests, at the northwest

- British Columbia mainland coastal forests, at the north

- Cascades Mountains leeward forests, small element of contact at the northeast

- Eastern Cascades forests, to the east and at the extreme south

References

- Charles R. Bacon; James V. Gardner; Larry A. Mayer; Mark W. Buktenica; Peter Dartnell; David W. Ramsey; Joel E. Robinson. 2002. Morphology, volcanism, and mass wasting in Crater Lake, Oregon. Geological Society of America Bulletin 114 (6): 675–692.

- Charles L. Bolsinger and Waddell, Karen L. 1993. Area of old-growth forests in California, Oregon, and Washington (PDF). United States Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Resource Bulletin PNW-RB-197.

- Lyn Topinka. 2002. Mount Rainier Glaciers and Glaciations. United States Geological Survey. U.S. Government Printing Office

- U.S. Forest Service. Mount Jefferson Wilderness: Deschutes. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Accessed Feb. 16 2015

| Disclaimer: This article contains some information that was originally published by the World Wildlife Fund. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the World Wildlife Fund should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |