Causes of forest land use change

Contents

- 1 Introduction The world's natural forests are experiencing land use change (Causes of forest land use change) due to both proximate (direct) and underlying (indirect) causes. Direct causes include immediate human land use activities that change forest cover in a local area. Key drivers include agricultural expansion, infrastructure development, wood extraction, climate change (Causes of climate change), fire and alien invasive species. Underlying causes result from social and institutional processes that may indirectly impact forest cover from a local, national, or international level. Prominent underlying causes include market failure and perverse incentives, corruption, inappropriate state policies and institutional failure, population pressure and poverty. In general, forest related land use changes have complex socio-economic, cultural and political foundations. One cannot assume simple and static cause-effect relationships.

- 2 Direct causes of forest land use change

- 3 Underlying causes of forest land use change

- 4 Further reading

Direct causes of forest land use change

Agricultural expansion

Source: IUCN

Source: IUCN Over the years, researchers have identified agricultural expansion as a major factor in almost all studies on deforestation. In the 1990s, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 70% of total deforested areas were converted to permanent agriculture systems. Despite the compelling figure, regional differences should be noted. For example, in Latin America conversion to agriculture has been large scale and permanent whereas in Africa small-scale agricultural enterprises have predominated. In Asia, the changes have been more equally distributed between permanent agriculture and areas under shifting cultivation.

Historically, increases in food production have been at the expense of millions of hectares of forest. With the expected clearance of additional forest land in the future for this purpose it is important to plan for this reality. However, equally important is acknowledging that technological innovations can have positive effects on forest areas and could, under certain circumstances, facilitate a transition from deforestation back to reforestation. If appropriate mechanisms are put in place to lock these gains in both developed and developing countries, this could potentially set a trend for large scale forest restoration in the future.

Infrastructure development

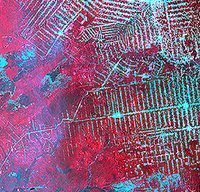

Remote sensing image of the impacts of road development on tropical forests in the state of Rondonia in the southwestern Amazon. The neat rows or strips in blue are land cleared for roads and agriculture. (Source: NASA)

Remote sensing image of the impacts of road development on tropical forests in the state of Rondonia in the southwestern Amazon. The neat rows or strips in blue are land cleared for roads and agriculture. (Source: NASA) Infrastructure development (road construction, dams, mining, power stations, etc.) is an important proximate cause of forest-related land use change. Road construction particularly, is a key factor in triggering deforestation as it tends to open up areas of undisturbed, mature forests to pioneer settlements, logging, and occasionally unsuitable forms of agriculture. The ensuing fragmentation also increases the exposure of forests to the dangers of poaching, alien invasive species, fires and pest outbreaks. In addition, the World Commission on Dams has documented the loss of forests and wildlife habitat, the loss of species populations and the degradation of upstream catchment areas due to large dams. Mining corporations and individual miners are also notably responsible for the clearance of large areas of forest in some countries. However, a recent study released by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) argues that in some cases increased incomes from oil and mining activities can have a macro-level effect on reducing the loss of tree cover in tropical countries.

Wood extraction

Another direct cause of forest land use change is wood extraction from natural forests. Despite the growing importance of plantations as a source of wood supply, wood extraction in the form of commercial timber, poles, fuelwood, and charcoal continues to degrade mature natural forests in many parts of the world. In the case of commercial logging, tree removal methods are frequently destructive and unsustainable. This is often the case on steep slopes and in sensitive ecosystems such as mangroves. Also, though many tropical countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America rely on logging timber for export earnings, according to World Bank estimates, illegal logging costs forest country governments at least US$ 10-15 billion a year – an amount greater that total annual development assistance for public education and health. Furthermore, a United Nations report attributes the severe pressure of illegal tree felling in protected areas and forests in the Central and Eastern European countries, and in the Former Soviet Union to increased poverty and to loss of traditional communist era livelihoods.

Fire

Deforestation and burning pastures in the Amazon. (Source: WWF)

Deforestation and burning pastures in the Amazon. (Source: WWF) Fires are a key driver of forest land use change. A United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) study estimates that annually fires burn up to 500 million hectares of woodland, open forests, tropical and sub-tropical savannas, 10-15 million hectares of boreal and temperate forest and 20-40 million hectares of tropical forests. Yet, fire is a paradox as while it can cause extensive ecological, economic, and social damage it can also be extremely beneficial through nutrient recycling and regeneration. For example in boreal forests, fire is a natural part of the forest cycle with some tree species, notably Lodgepole Pine and Jack Pine being able to germinate only after they have been exposed to fire. In addition, burning quickly decomposes organic matter into mineral components that cause a spurt of plant growth, and can also reduce disease in the forest. Nevertheless, forest fires in contrast have caused considerable environmental, health, economic and social damages in recent years and have been recognized as major cause of forest loss and degradation in some parts of the world. Furthermore, emissions from forest fires have also exacerbated global climate change.

Climate change

Current and projected ranges of beech trees in the US due to climate change. (Source: EPA)

Current and projected ranges of beech trees in the US due to climate change. (Source: EPA) Although many forests have proved relatively resilient to past [[climate change]s], today's fragmented and degraded forests are more vulnerable, with up to 30% of forests likely to be affected by climate change by the year 2050 according to an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) report. The impacts will however be differential depending on forest type and species. For example, while enhanced photosynthesis and/or tree growth has been observed in some regions of the world, permafrost thawing in central Alaska threatens natural lowland birch forest. Higher temperatures and changes in rainfall also threaten tropical montane forests, boreal forests and Mediterranean-type, fire-prone forests. Furthermore, the effects of greenhouse gases can impact the highly species-specific phenology of forest trees, affecting the processes of budding, flowering, fruiting, leaf senescence, frost hardiness, wood quality, branching and insect susceptibility. While pest and disease infestations are part of the natural forest cycle, the risk of serious outbreaks increase with more changes in climate. In addition, extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, pose other risks to forest ecosystems.

Alien invasive species

As the global movement of people and products spreads, so does the movement of plant and animal species from one part of the world to another. When a species is introduced into a new habitat – for example, oil palm from Africa into Indonesia, Eucalyptus species from Australia into California, and rubber from Brazil into Malaysia – the alien species typically requires human intervention to survive and reproduce. Often these alien species are economically important and enhance the production of forest commodities in many parts of the world. However, in some cases species introduced intentionally become established in the wild and spread at the expense of native species, affecting entire ecosystems. Perhaps even worse are invasive alien species that are introduced unintentionally, such as disease organisms that can devastate an entire tree species (e.g. Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight in North America) or pests that can have a major effect on native forests or plantations (e.g. gypsy moths and long-horned beetles). As global trade grows, so does the threat from devastating invasive species of insect and pathogen. These could fundamentally alter natural forests and wipe out tree plantations, the latter being especially vulnerable because of their lower species diversity.

Underlying causes of forest land use change

Forest land use change is seldom straightforward, often being driven through a complex mix of socio-economic, cultural, and political factors. Such factors in turn result from the combined actions, decisions and behavior of multiple agents ranging from national governments to international financiers to impoverished landless people.

Poverty

Poverty is popularly cited as a principal driver of forest loss and degradation. In reality, however, the evidence for such a straight-forward relationship is weak and sometimes conflicting. The empirical evidence for the historical relationship between economic growth, a growing middle class, consumption levels and forest decline is perhaps a little better understood but also remains weak and fragmented. What is evident however is that there is a causal relationship, or more accurately several relationships, that need to be better understood. More reassuringly, there is some, yet again fragmented, evidence that no single trajectory is necessarily predetermined and that forest resources, under a range of circumstances, can be managed and utilized in such a way as to contribute to poverty reduction while keeping future options open to retain more and lose less forest biodiversity.

Imperfect local, national, and international markets

While the contribution of forest goods and services for local livelihoods, national economic growth and as a global public good are regularly highlighted, there is a considerable gap between the acknowledgment of these benefits and how they are actually "valued". In many countries forests goods and services continue to be undervalued because in the absence of suitable markets, forests, as a land-use, are unable to compete, either with other land-uses or with other sectors such as energy. New markets could arise if the provision of key public utilities was viewed slightly differently. For example, clean and reliable water supply requires not only the hard infrastructure of pipes and reservoirs, but also the "green" infrastructure in watershed catchments. Equally production-based incentives for other land-use activities, notably agriculture, also help drive forest loss and degradation.

Absence of Good Governance and Rule of Law

Government policies, and how those policies are enforced, both within and outside the forest sector, also ultimately impact on forest land use change. Forest land is still all too often seen as a nationally-owned asset, irrespective of the stewardship that local communities have exercised over the same resource for many years. Inequities in titling and use rights can result in forests becoming a major source of conflict and / or illegal activity. While illegal logging and corruption may, and often does, exist because of pure criminality it can, in some situations, be driven by inappropriate governance structures that turn legitimate concerns or entitlements into illegal activities. For example, in one Central American country in the early 1990s one of the main causes for bribery associated with log transport permits was not that loggers want to move illegally harvested trees but rather that they wanted to avoid long bureaucratic delays in attaining permission that would leave legally harvested trees deteriorating in forest loading yards.

Demographic factors

A common myth of the 1990s was that increasing populations was a major underlying cause of forest decline. Available evidence shows that there is no general relationship between population growth and density and deforestation. Indeed there are a number of examples in both developed and developing countries of how population increase has been accompanied by increasing tree cover. There are many examples particularly where fuelwood and agricultural land is in much demand and other livelihood options, are limited, of population growth and density resulting in increased pressure on forests although these then tend to be quite localized. Importantly, demographic factors associated with mortality and morbidity, particularly where the HIV/AIDS pandemic is concerned, may be just, if not more, significant when it come to forest-related land-use change.

Further reading

- Forest Conservation Programme, The World Conservation Union

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the The World Conservation Union. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the The World Conservation Union should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |