Canary Current large marine ecosystem

The Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean and is characterized by its temperate climate. This LME, situated off the coast of Northwest Africa, shows major upwelling and other seasonal nutrient enrichments.

Climate is the primary force driving the LME, with intensive fishing as the secondary driving force. Hydrographic and climatic conditions play a major role in driving the dynamics of this LME, showing seasonal and longer-term variations (see Bas, 1993). The Global Environmental Facility (GEF) is planning to support an LME project in the Canary Current LME. The Canary Current is strongest near the coast, becoming progressively weaker offshore. It accelerates as it passes between the Canary Islands and the coast.

The islands produce shade zones, with warmer water south of the islands and an accumulation, there, of marine resource biomass (see Hernandez-Leon, 1988). LME book chapters and articles pertaining to this LME include Bas, 1993, Prescott, 1993, and Roy and Cury, 2003.

Contents

- 1 Productivity

- 2 Fish and Fisheries

- 3 Pollution and Ecosystem Health

- 4 Socioeconomic Conditions

- 5 Governance

- 6 References

- 6.1 Articles and LME volumes Bas, Carlos, 1993. "Long-term Variability in the Food Chains, Biomass Yields, and Oceanography of the Canary Current Ecosystem," in Kenneth Sherman, et al. (eds.), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability (Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science) pp.94-103. ISBN: 087168506X (Canary Current large marine ecosystem) . * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems—2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Prescott, J. R. V., 1993. Role of National Political Factors in the Management of LMEs: Evidence from West Africa. In Kenneth Sherman, Lewis M. Alexander, and Barry D. Gold (eds). Large Marine Ecosystems-Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability. AAAS Press. 280-291. ISBN: 087168506X. * Prescott, J. R. V., 1989. The Political Division of Large Marine Ecosystems in the Atlantic Ocean and some associated seas. In Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander (eds). Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. Westview Press. 395-442. ISBN: 0813378443. * Roy, C. and P. Cury, 2003. Decadal environmental and ecological changes in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem and adjacent waters: Patterns of connections and teleconnection. In: K. Sherman and G. Hempel, Large Marine Ecosystems of the World – Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. ISBN: 0444510273.

- 6.2 Other references

- 6.3 Citation

Productivity

Oceanic conditions show both seasonal and long-term variations. For a study of the physical oceanography of the area, see Bas, 1993. The Canary Current LME is classified as a Class I, highly productive (>300 grams of Carbon per square meter per year (gC/m2-yr)), ecosystem based on global primary productivity estimates from SeaWiFS. The region supports fish and also migratory birds. Contact between the Canary Current and the shade zones described above results in two eddies; a cyclonic gyre in the west and an anticyclonic gyre in the east. These are areas of zooplankton accumulation (see Bas, 1993). The zooplankton community is generally composed of copepods, but mysidacea are also important in all regions. Productivity is high around the upwelling centers. For a study of the upwelling process, winds, seasonal patterns, and surface temperature trends and anomalies, See Roy and Cury, 2003. This article explores decadal changes in the Canary Current LME.

Fish and Fisheries

Commercial species in this LME include sardines, pilchards, horse mackerel, chub mackerel and hake.

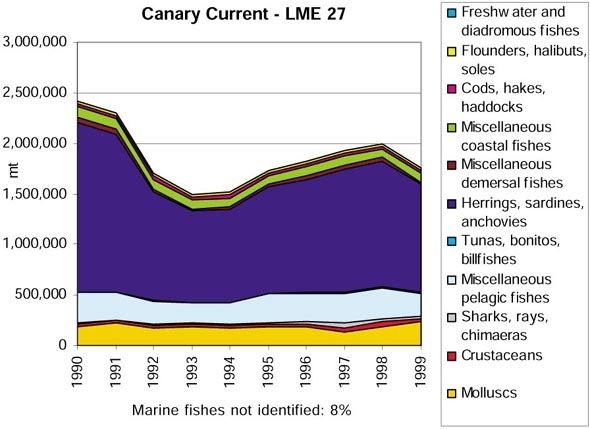

Five decades of observation have shown the high variability of this LME driven by an upwelling regime. There have been dramatic fluctuations in fish and fisheries. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 10-year trend (1990-1999) shows a decline in the catch from 2.3 million tons in 1990 to 1.8 million tons in 1999 ( FAO, 2003). There were sharp declines in 1992, 1993, and 1994. More than 60% of the catch is composed of small pelagic clupeoids (herring, sardines, anchovies). For a description of, and data for, the LME’s important fisheries, see Bas, 1993. For more information on fisheries and fish population patterns, see Roy and Cury, 2003. There is an obvious impact of upwelling intensity and SST on the spatial distribution and abundance of fish.

The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) has issued a matrix that ranks LMEs according to the sustainable exploitation of fisheries and the predicted direction of future changes. GIWA characterizes the LME as severely impacted in terms of overfishing, with severe economic consequences especially in the Southern part of the LME. However, these impacts are decreasing. For information about the pelagic species Scomber japonicus and its predator/prey interactions with other stocks and with zooplankton (copepoda and mysidacea), see Gonzalez and Bas (1989).

Canary Current fisheries are increasingly under pressure from highly subsidized foreign fishing fleets originating from the European Union countries. These countries want more fishing access. Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal need to assess the sustainability of their fisheries resources. These countries’ lack of resources has been an obstacle to the establishment of an effective monitoring system for the LME. The University of British Columbia Fisheries Center has detailed long term fish catch statistics for this LME.

Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Migration to the [[coast]al] cities of West Africa has been accelerated by the increasing desertification of the interior. This is placing additional pressure on the coastal areas. Many pollution issues affecting this LME are associated with urban and industrial development along the coast. Additional problems are runoff as a product of soil erosion, the release of agrochemical products and sewage discharge. Senegal, Mauritania and Guinea-Bissau are aware of these issues and are taking measures to enhance the protection of some of their more fragile marine environments.

The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) has issued a matrix that ranks LMEs according to the destruction and degradation of [[ecosystem]s], habitat and community modification, pollution and global change. GIWA characterizes the LME as severely impacted in the area of modification or loss of ecosystems or ecotones and health impacts. These impacts, however, according to GIWA are decreasing. Moreover, the Northern part of the LME is less impacted. For more information on combating water pollution in this LME, visit GIWA's Canary Current page.

Socioeconomic Conditions

The 8 [[coast]al] countries bordering the Canary Current LME are dependent on its marine resources such as fish, phosphates and oil. The fishing industry is an important sector of the economy of all 8 countries, fulfilling their needs for food. Morocco has a vigorous fishing industry. Senegal’s industry, employing about 100,000 people, consists of small-scale artisanal fishing and large-scale trawler fishing. 600,000 people in Senegal, Mauritania and Guinea-Bissau are directly dependent upon fishing for their incomes. The depletion of fishing stocks, and the pressure from highly subsidized fishing fleets originating from the European Union countries has economic consequences. The migration of workers from rural inland areas to the coast stretches the coastal capacity to provide infrastructure and services.

Governance

Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, the Canary Islands (Spain), Gambia, Cape Verde (Cape Verde Islands dry forests) and Western Sahara are the countries bordering the Canary Current LME. The Global Environment Facility (GEF) is supporting an LME project in the Canary Current LME, which involves Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Morocco and Senegal. The project will conduct a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA), which will analyze factual and scientific information on transboundary concerns and their root causes, and set priorities for action. It will help determine national and regional policy, legal and institutional reforms and investments needed to address priorities within the LME. The most pressing issues relate to the destruction and degradation of [[ecosystem]s] and overfishing. While there is an obvious advantage to the cooperation of these countries especially in terms of dealing with the foreign fishing problem, the coordinated management of this LME is difficult (see Prescott, 1993).

The fragmented nature of coastal and marine resource management is a legacy of the colonial past and of the political situation of these countries, all of which are former colonies of Europe except for the Canary Islands (still today a part of Spain). The status of the former Spanish Sahara, now called Western Sahara and occupied by Morocco, is uncertain. There is a relative absence of inter-agency (or inter-ministerial) frameworks for addressing transboundary problems and managing the marine environment and its resources. There are regionally incompatible laws and a paucity of environmental regulations. Senegal and Guinea-Bissau are developing marine protected areas. Mauritania is seeking to ban all commercial fishing from the coastal wetlands of a national park. For more information on possible ecosystem management approaches, and governance issues in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem, visit GIWA's Canary Current page.

References

Articles and LME volumes Bas, Carlos, 1993. "Long-term Variability in the Food Chains, Biomass Yields, and Oceanography of the Canary Current Ecosystem," in Kenneth Sherman, et al. (eds.), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability (Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science) pp.94-103. ISBN: 087168506X (Canary Current large marine ecosystem) . * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems—2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Prescott, J. R. V., 1993. Role of National Political Factors in the Management of LMEs: Evidence from West Africa. In Kenneth Sherman, Lewis M. Alexander, and Barry D. Gold (eds). Large Marine Ecosystems-Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability. AAAS Press. 280-291. ISBN: 087168506X. * Prescott, J. R. V., 1989. The Political Division of Large Marine Ecosystems in the Atlantic Ocean and some associated seas. In Kenneth Sherman and Lewis M. Alexander (eds). Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. Westview Press. 395-442. ISBN: 0813378443. * Roy, C. and P. Cury, 2003. Decadal environmental and ecological changes in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem and adjacent waters: Patterns of connections and teleconnection. In: K. Sherman and G. Hempel, Large Marine Ecosystems of the World – Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. ISBN: 0444510273.

Other references

- Barton, E. D., J. Arístegui, P. Tett, M. Cantón, J. García-Braun, S. Hernándex-León, L. Nykjaer, C. Abneida, J. Almunia, S. Ballesteros, G. Basterretxea, J. Escánez, L. García-Weill, A. Hernández-Guerra, F. López-Laatzen, R. Molina, M. F. Montero, E. Navarro-Pérez, J. M. Rodríguez, K. van Lenning, H. Vélez, and K. Wild, 1998.The transition zone of the Canary Current upwelling region. Progr. Oceanogr., 41:-504, 1998.

- Castro, J.J., et al. 1989a. The population of Somber japonicus in Canary Islands; feeding and growth aspects. Poster presented at the International Symposium on Fish Population Biology, July 17-21, 1989. Aberdeen, Scotland.

- Castro, J.J., et al. 1989b. Interaction between Somber japonicus and Katsuwonus pelamis in the southern area of Canary Islands. CIEM. La Haja.

- Gonzalez, A.J. and Bas, C. 1989. The influence of environmental conditions of the skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) in the Canary Island waters. Poster presented at the International Symposium on Fish Population Biology. July 17-21, 1989. Aberdeen, Scotland.

- Hernandez, Leon, S. 1988. Gradients of mesozooplankton biomass and ETS activity in the wind shear area as evidence of an island mass effect in Canary Island waters. J of Plankton Res. 10:1141-1154.

- Longhurst, A.R. and D. Pauly, 1987. Ecology of tropical oceans. Academic Press, London. 407p. ISBN: 0124555624.

- Mergalef, R. 1972. Fitoplancton de la región de afloramiento del NW de Africa. Pigmentos y producción. (Campaña Sahara II de Cornide de Saavedra). R. Exp. C. Cornide. 1:23-51.

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |