Arkansas River

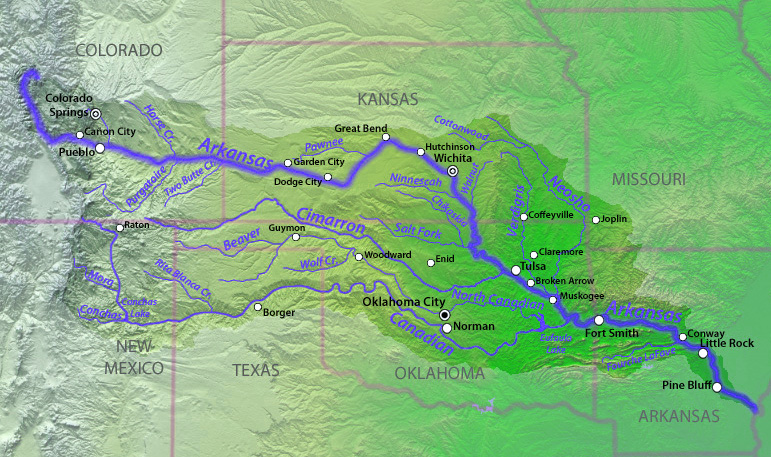

The Arkansas River, the sixth largest in the United States, rises in the Collegiate Peaks of Colorado and discharges to the Mississippi River.

The river course is commonly divided into four reaches:

- Southern Plains;

- Central Prairie;

- Ozark Plateau; and,

- Mississippi Embayment.

The western portion of the catchment basin consists of about one half grazing and one half cropping uses, while the eastern reaches beginning around the Ozark Plateau contain approximately half forested land cover.

Catchment basin of the Arkansas River. Source: Creative Commons

Catchment basin of the Arkansas River. Source: Creative Commons

Contents

Hydrology

The Arkansas River rises near Leadville, Colorado at an elevation of approximately 3010 meters about thirty kilometers north of Mount Elbert, Colorado's highest peak.

|

|

North American beaver are common on many tributaries. Source: Creative Commons North American beaver are common on many tributaries. Source: Creative Commons

|

|

|

Flint Hills in the Arkansas River catchment basin. Flint Hills in the Arkansas River catchment basin.

|

|

|

Tthe upper reaches of the Arkansas River manifest turbulent high gradient passage through rugged volcanic terrain; the flow continues to the Royal Gorge, where one of the world's highest suspension bridges towers 320 meters above the river surface; thereafter, the river course flows generally eastward through Kansas, thence southeastward through Oklahoma and Arkansas until its discharge to the Mississippi River. The river basin also includes parts of the states of New Mexico, Texas and Missouri.

Chief tributaries of the Arkansas River are Purgatoire River, Fountain Creek, Pawnee River, Salt Fork River, Illinois River,Verdigris River, Neosho River, Cimarron River and the Canadian River.

The mean annual discharge at Little Rock, Arkansas is approximately 1118 cubic meters per second, a level remarkably undifferentiated from virgin flow, before the era of locks, impoundments and extraction.

Water quality

Water quality at the headwaters near Leadville, Colorado is quite high, consisting of cold, rapidly flowing water of pH 6.3. Concentrations of calcium, sodium, Magnesium and chloride are all less than ten milligrams per liter in this pristine headwaters area.

Crossing the Southern Plains below Great Bend, Kansas, the pH elevates to a level of 8.0, sodium concentrations rise to a range of 300 to 500 mg/l, with other ions rising by similar large percentages. After receiving the more pristine runoff from the Ozark Plateau, below Fort Smith, Arkansas, the pH level can be measured as low as 7.5, and sodium along with other ion concentrations are reduced by a factor of four.

At the Mississippi Embayment, nitrate and phosphate levels are elevated due to row crop agricultural runoff of this region.

Aquatic biota

The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is common along tributaries, especially at points near the mainstem.

A number of crayfishes are found in the Arkansas River, including Orconectes palmeri, O. nais, O. virilis, Procambarus acutus and P. simulans.

In the downstream reaches of the Mississippi Embayment a number of commercially important native freshwater mussels occur, including the threeridge mussel (Amblema plicata) and mapleleaf mussel (Quadrula quadrula). Other common freshwater mussels found in the Arkansas River and its tributaries are the pink papershell (Potamilus ohiensis), bleufer (P. purpuratus), fawnsfoot (Truncilla donaciformis), fragile papershell (Leptodea fragilis), pondhorn mussel (Uniomerus tetralasmus) and fluted shell mussel (Lasmigona costata).

There are 141 species of fish present in the Arkansas basin, (Benke. 2005) including two benthopelagic (living near the bottom) endemics: slough darter (Etheostoma gracile) and speckled darter (Etheostoma stigmae). The federally threatened and near-endemic Neosho madtom (Noturus placidus) occurs in the Neosho River, a tributary that rises in the Flint Hills. Also present in the Neosho River is the endangered Topeka shiner (Notropis topeka). The cardinal shiner (Luxilus cardinalis) is a near-endemic that is now restricted to populations in the Arkansas River and Red River, and disjunctive populations in the Neosho River.

The rare Arkansas chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) is found in restricted reaches of the basin: Ninnescah River and an associated portion of the Arkansas River in Kansas and the South Canadian River between Ute and Meredith reservoirs. There are two pelagic-neritic (brackish water tolerant) native fishes in the Arkansas River system include the 62 centimter (cm) Alabama shad (Alosa alabamae) and the 15 cm Inland silverside (Menidia beryllina).

In the upper Arkansas River mainstem is found the plains leopard frog (Rana blairi); also occurring in the upper basin are a number of reptiles, including yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens), midland smooth softshell (Apalone mutica), western spiny softshell turtle (Apalone spinifera hartwegi) and northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon). In the downriver portions of the basin (Eastern Oklahoma and Arkansas) are found the false map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) and the venomous cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus).

Riparian birds in the basin include the belted kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon), green heron (Butorides virescens), great blue heron (Ardea herodias) and little blue heron (Ardea herodias).

Terrestrial ecoregions

The Arkansas River Basin traverses a number of USA ecoregions, including (west-to-east):

- Colorado Rockies forests (headwaters to the end of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains)

- Western short grasslands (eastern Colorado and western Kansas)

- Central and Southern mixed grasslands (central Kansas into Oklahoma)

- Flint Hills tall grasslands (north-side of the River as it passes from Kansas into northeast Oklahoma)

- Central forest-grasslands transition (center stretch of the river through Oklahoma)

- Ozark Mountain forests (eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas)

- Mississippi lowland forests (eastern Arkansas to the Mississippi River)

The Western short grasslands cover the Arkansas River Basin in extreme southeast Colorado, northeast New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle and extreme southwest Kansas. This grassland ecoregion is distinguished from other grassland units by low rainfall, relatively long growing seasons, and warm temperatures. From a structural standpoint, the short stature of the dominant sod-forming grasses, grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides), separate the Western short grasslands from other units.

The Central forest-grasslands transition occupies a small portion of the Arkansas River basin in the Missouri Osage Plains and Oklahoma Cross Timbers area. Oaks and hickories are the dominant tree species throughout the unit but often occur at low to moderate densities. Typical oaks are blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica) and post oak (Quercus stellata) in the southern part of this ecoregion. Bison (Bison bison) were abundant in this ecoregion in the presettlement period.

The Flint Hills and adjacent Osage Hills contain the last large pieces of tallgrass prairie in the world. The Flint Hills is less rich in species than the Central Tall Grasslands. The dominant grass species in this ecoregion are big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans).

The Ozark Mountain forests are comprised chiefly of the Ouachita and Boston Mountains, whose forests are among the best developed oak-hickory forests in the USA. The primary species here are red oak (Quercus rubra), white oak (Q. alba), and hickory (Carya spp, especially Carya texana). Shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) and eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) are important on disturbed sites, shallow soils, and south- and west-facing slopes.

River swamp forests, dominating the Mississippi lowland forests, which are adapted to continuous flooding, contain baldcypress (Taxodium distichum) and water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica), which often codominate the canopy. Associated with river swamp forests are button bush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), water ash (Fraxinus caroliniana), water-elm (Planera aquatica), and black willow (Salix nigra). Lower hardwood swamp forests are similar to river swamp forests, but have a more diverse woody community. Water hickory (Carya aquatica), red maple (Acer rubrum), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) and river birch (Betula nigra) increase in prevalence. Common herbs include butterweed (Senecio glabellus), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), and royal fern (Osmunda regalis). Forests of backwaters or flats make up a third zone, and are seasonally saturated. They support a greater richness of hardwood species. In addition to lower hardwood swamp species, sweetgum (Liquidamber styraciflua), sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), and willow oak (Quercus phellos) are present. Woody vines increase in abundance, including poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), greenbriers (Smilax spp.), and trumpet-creeper (Campsis radicans). At the transition to upland forests are ridges and dunes formed during the Pleistocene, as well as natural levees.

The skyline of Little Rock, Arkansas viewed from the north bank of the Arkansas River. Source: Matthew Field

Prehistory

Clay effigy from the Spiro Mound site, whose civilization peaked 800 to 1400 AD. Source: Herb Roe Since the early Holocene the lower Arkansas River valley was occupied by Paleo-Indians. Some of the iconic archaeological sites in this basin include the bluff dweller sites of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains of extreme southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas; other notable Native American sites are mound-building cites such as the Spiro site of eastern Oklahoma; these sophisticated mound-builders thrived in the era 800 to 1400 AD over most of the Arkansas and Oklahoma portions of the Arkansas River basin, and were known as the Caddoan Mississippian culture. Precursor civilizations to the Caddoan Mississippian culture in this region include the Fourche Maline culture that thrived from 200 BC to 800 AD.

Clay effigy from the Spiro Mound site, whose civilization peaked 800 to 1400 AD. Source: Herb Roe Since the early Holocene the lower Arkansas River valley was occupied by Paleo-Indians. Some of the iconic archaeological sites in this basin include the bluff dweller sites of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains of extreme southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas; other notable Native American sites are mound-building cites such as the Spiro site of eastern Oklahoma; these sophisticated mound-builders thrived in the era 800 to 1400 AD over most of the Arkansas and Oklahoma portions of the Arkansas River basin, and were known as the Caddoan Mississippian culture. Precursor civilizations to the Caddoan Mississippian culture in this region include the Fourche Maline culture that thrived from 200 BC to 800 AD.

History

The earliest recorded history of the Arkansas River basin traces to the mid sixteenth century, when the Spanish explorer Desoto noted populous fortified Native American villages along the Arkansas River. In the western portion of the basin principal Indian tribes were the nomadic Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapajo and Comanche. Earnest exploration of the upper basin did not commence until about 1806, subsequent to the Louisianna Purchase.

References

- Arthur C.Benke & Colbert E.Cushing. 2005. Rivers of North America. 1144 pages Google eBook

- James Allison Brown & Alice Brues. The Spiro Ceremonial Center: The Archaeology of Arkansas Valley Caddoan Culture in Eastern Oklahoma, Ann Arbor: Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, 1996.

- Arrell Morgan Gibson. 1981. Oklahoma, a history of five centuries. books.google.com 316 pages

- Claudette Marie Gilbert, Robert L. Brooks. 2000. From mounds to mammoths: a field guide to Oklahoma prehistory. University of Oklahoma Press. books.google.com 113 pages

- Henry Hamilton, Jean Tyree Hamilton, & Eleanor Chapman. Spiro Mound Copper, Columbia, MO: Missouri Archaeological Society, 1974.

- J.C. Kammerer. 1990. Largest Rivers in the United States. United States Geological Survey. Washington DC

- World Wildlife Fund. 2002. Ozark Mountain forests; Flint Hills tall grasslands; Mississippi lowland forests