|

Worms

|

Flat worms

Introduction

The term flat worm refers to the physical shape of the worm parasite. The flat worms are also called tape worms

Tape worms

Tapeworms are a type of flat worm belonging to a class of worms called cestodes. They consist of a number of sections, occurring one after the other. Each section contains separate reproductive organs but the nervous and excretory systems are continuous throughout the whole worm. The head part is called the scolex and contains hooks, or suckers. The separate sections, called proglotides, develop from the scolex, one by one, to make a chain. The sections furthest from the head are the oldest. Almost all domestic and wild animals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles can be infested by different species of tapeworm.

Generally speaking, tapeworms have little apparent effect on the health of farm animals. Heavy infestations in young animals may cause failure to grow fast. Although tapeworms may infest animals of any age they appear to have little adverse effects on adults, and heavy infestations are required to cause clinical illness in the young.

The intermediate stages of some tapeworms may have serious effects in humans if the eggs of these tapeworms are swallowed by people.

Life cycle of tape worms

The general life cycle of tape worms occurs in two hosts, the final or principal host, and the intermediate host.

The eggs of the adult worm are fertilized within the hermaphrodite worm and develop into embryos in the uterus within a segment (proglotid).

The eggs of the adult worm are fertilized within the hermaphrodite worm and develop into embryos in the uterus within a segment (proglotid).

This segment will break off from the rest of the chain and is passed out of the body of the host in the faeces after degeneration of the proglotid to form a sac of embyonated eggs. Within the egg of all tape worms, an embryo develops which is eaten by the intermediate host where it is transformed into a bladder like structure. The embryo may be transformed into one big bladder like structure with numerous invaginated walls called a coenurus.

The embryo may also be transformed into one bladder like structure with one invagination in the wall called a cysticercus. In Echinococcus granulosus species of tape worm, the bladder like structure may develop to form daughters and grand daughters called hydatid cysts.

The coenurus, cysticercus and hydatid cysts will each produce at the base the scolex or head, including the hooks which will become the scolex of the future worm in the final host.

When this larval stage enters the final host when the intermediate host is swallowed by the final host the head fixes itself into the tissues of the final host to begin a new adult phase.

Mature tapeworms only develop when the final host ingests the intermediate stage. The intermediate hosts in the common tapeworms of ruminants are oribatid mites.

Some important adult tape worms of cattle

1. Monieza benedeni

This occurs in ruminants, mainly cattle. It is present in most parts of the world. The life cycle is through oribatid mites. The eggs, or shed proglotides containing eggs, are eaten by the final host in 2 - 6 months. Mites are present on grazing pastures in large numbers. The mites are eaten by grazing animals and larvae develop in the intestine into adult tape worms in about 6 weeks. The adult tape worm lives for about 3 months in the final host.

|

|

|

2. Avittelina species

These occur in the small intestines of cattle and other ruminants. They are present mainly in Africa and India. The adult tape worm measures about 3 meters long and 3mm wide.

3. Thysaniezia giardi

This occurs in the small intestine of cattle, sheep and goats, mainly in Africa. The life cycle is through oribatid mites.

Clinical signs and diagnosis

General clinical signs of adult tape worm in cattle.

The effect of adult tape worms in cattle may not be serious. However, heavy infestations may cause disease, especially in the presence of other stress factors like nutritional deficiencies or bacterial infections.

The clinical effects include a dry coat, digestive disturbance, pot belly, anaemia and oedema. When present in large numbers, tape worms can cause blockage of the intestines. Diarrhoea and constipation may sometimes be observed.

Diagnosis

This is made by observing tape worm segments in the faeces or intestines, or from the presence of the tape worm eggs in the faeces. The presence of the eggs in the faeces can be demonstrated by direct smear or by the flotation technique in the laboratory.

Post mortem examination

- Tape worms may be present in the small intestine or in the bile ducts.

- The carcass may be pale and emaciated (thin)

- The walls of the intestines may show ulcerations with inflammation on the wall where the hooks of tape worms have caused a reaction

- Presence of segments in the faeces.

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Control /preventive measures

- Attempts to control the mites on the pastures are generally not practical

- Use of drugs is the most important effective control method.

Treatment

The following are some of the available effective drugs that can be used for treatment of tape worms:

- Niclosamide, Morantel, Praziquantel, Albendazole, Fenbendazole, and Oxfenbendazole are effective against tapeworms in cattle and sheep and dogs.

Larval tape worm infestation in cattle

A number of tapeworms are of significance as they involve humans and domestic dogs.

1. Taenia saginata.

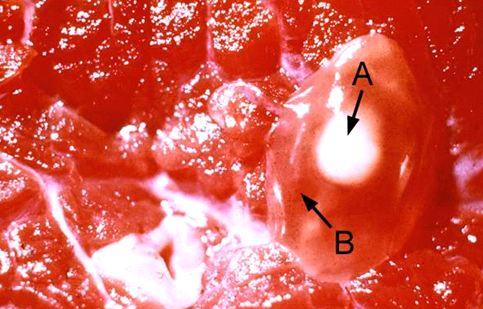

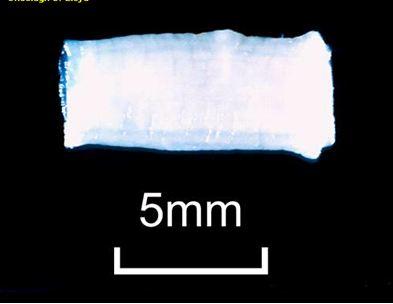

This is a tapeworm of humans, in which it can cause abdominal discomfort.It is a very long tapeworm, growing up to 15 metres long. Its main relevance is that cattle are the main intermediate hosts. In cattle the embryos locate in skeletal and heart muscle tissue where they appear as small white oval nodules, visible to the naked eye. These, if swallowed by a human, will develop into a mature tapeworm. This stage is called cysticercus bovis or measles. At meat inspection if these measles are found the carcass will be detained and held at low temperatures until fit to be passed for human consumption. Eating raw or undercooked meat is highly dangerous and can result in infestation with Taenia saginata.

|

|

||||||

|

|

| 2. Taenia hydatigena

This is a dog tapeworm and cattle are often internediate hosts. If dogs have access to the liver or peritoneal tissues of infected cattle they may become infested with the adult tapeworm.

|

|

3. Taenia multiceps multiceps

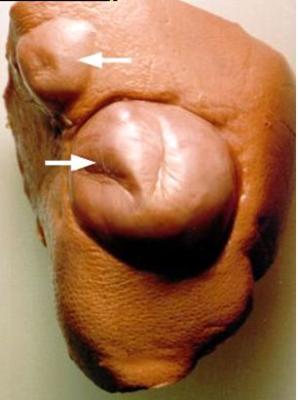

This is a dog tapeworm whose main relevance is that the intermediate stage, called coenurus cerebralis, forms large cystic structures, often in the brain or spinal cord, of the internediate host, which is often a sheep, goat,antelope, or occasionally cattle. Dogs acquire the final tapeworm by eating affected nervous tissue.

| 4. Echinococcus granulosus

This is a very short dog tapeworm, whose main significance is that the larval stage forms large multiple hydatid

cysts in the intermediate hosts, including humans. These cysts are located in the liver and lungs and can grow to a very large size indeed. People living in close association with dogs are especially at risk.

|

|

Symptoms or clinical signs

Symptoms observed in the intermediate host vary depending on the organ of the body which is affected.

Taenia multiceps multiceps has no apparent effect in the canine (dog) host. However, the larval stage, coenurus cerebralis, can reach the brain of susceptible intermediate host ruminants such as sheep and goats and antelope and cause intracranial pressure resulting in staggering, blindness, head deviation, stumbling and paralysis. This condition is known as gid or sturdy. Palpation of the skull may reveal a soft spot which may allow a skilled veterinary surgeon the opportunity to remove the causal cyst. Dogs associated with sheep should never be fed offal, brain or spinal cord from sheep and they should be dewormed regularly.

Taenia multiceps multiceps has no apparent effect in the canine (dog) host. However, the larval stage, coenurus cerebralis, can reach the brain of susceptible intermediate host ruminants such as sheep and goats and antelope and cause intracranial pressure resulting in staggering, blindness, head deviation, stumbling and paralysis. This condition is known as gid or sturdy. Palpation of the skull may reveal a soft spot which may allow a skilled veterinary surgeon the opportunity to remove the causal cyst. Dogs associated with sheep should never be fed offal, brain or spinal cord from sheep and they should be dewormed regularly.

Diagnosis

Lesions are likely to be found during meat inspection or at postmortem: Cysticercus bovis, the intermediate stage of the human tapeworm Taenia saginata, will be found embedded in the following parts of cattle: heart, tongue, diaphragm and cheek muscles.

Coenurus cerebralis, the larval stage of Taenia multiceps multiceps is usually found in the brain or spinal cord of sheep or goats. The animals are normally emaciated and anaemic. Cysts may also be found in the lungs and liver.

Accurate diagnosis can be done from samples collected by qualified personnel and analyzed at the laboratory.

Treatment

Treatment for larval stage of taeniids is not practical in animals, although effective treatment for hydatid cysts in humans exists.

Prevention and control

The principle of a proper control program aims at the following:

- Breaking of the life cycle by treatment of the principal host (human, dog, cattle sheep etc)

- Destruction of tissues of the intermediate host containing cysts

- Destruction of eggs during the passage from principal host to intermediate host

The most effective control method should ensure the following:

- Treatment of infected humans and dogs

- Good meat inspection procedures by qualified meat inspectors and destruction of infected tissues or meat

- Educating the public about the dangers of eating raw or partially cooked meat. The meat to be eaten by humans should be cooked at temperatures above 60 degree Celsius or be frozen below 10 degree Celsius for 10 days. These treatment methods are sufficient to destroy the cysts.

- Use of pit latrines to keep human waste away from animals, especially dogs. The public should be enlightened about the dangers of using human waste as fertilizer.

- Fencing of slaughter houses with dog proof fences will keep stray dogs away and prevent them from eating condemned meat that may be infected with cysts.

- Dogs should be de-wormed on a regular basis

Liver Flukes

Local names:

Embu: nthambara / Gikuyu: thambara cia mani / Kamba: ntambaa / Kipsigis: sungurutek / Luo: ochwe / Maragoli: ovoveyi / Meru: nthanthara / Samburu: ikurui, lemonyua / Somali Ethiopia: faraqle / Somali Kenya: sogul / Masai: Osinkirri

Embu: nthambara / Gikuyu: thambara cia mani / Kamba: ntambaa / Kipsigis: sungurutek / Luo: ochwe / Maragoli: ovoveyi / Meru: nthanthara / Samburu: ikurui, lemonyua / Somali Ethiopia: faraqle / Somali Kenya: sogul / Masai: Osinkirri

Family: Trematoda

Description: Parasite

|

Introduction

There are two important species of liver flukes in Kenya: fasciola gigantica and fasciola hepatica. The former is more important, being found throughout the lower warmer parts of the country. As the name suggests it is very large, more than twice the size of fasciola hepatica, which is found in the cooler highland areas of the country, and also in the temperate zones of the world such as Europe,North America, Australia and New Zealand.

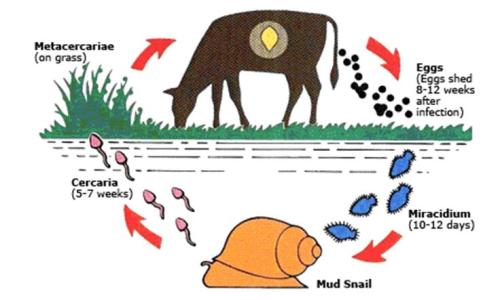

The life cycle of liver flukes involves a snail, which acts as an intermediate host. If there is no snail there will be no flukes. The snail involved requires still, stagnant water to survive; swift running water does not suit it. Swamps, ponds, lakes with a marshy edge and pools of water edged by vegetation are danger zones for grazing animals.

Cattle, sheep and goats are mainly affected, although other animals such as donkeys, horses, and many species of wildlife such as buffalo can also be infested. Humans can also be infested with liver flukes.

As the name suggests, the liver fluke attacks the liver.

Three forms of illness can occur:

1. It can cause sudden death, either from liver failure or from haemorrhage, when large numbers of immature flukes migrate through the liver.

2. It can be the cause of a chronic wasting disease accompanied by anaemia and oedema (swelling).

3. It can also be the causative factor in Infectious Necrotic Hepatatis (Black Disease) of sheep, when toxins released from the bacteriun Clostridium Novyi type B multiply in the wounds caused by the migrating flukes. Sudden death is the result.

|

|

| Life cycle of liver flukes

A knowledge of the life cycle of the liver fluke is an aid in understanding how to control the disease.

The life cycle of fasciola gigantica and hepatica both follow the same pattern. The intermediate host snail may differ but in other respects the life cycle is the same.

Mature flukes are long lived and sheep and cattle may be carriers for years.

The intermediate host snail for fasciola hepatica is called lymnea truncatula.The host snail for fasciola gigantica is lymnea natalensis,but sometimes also truncatula.

|

|

Signs of Liver Flukes

The severity of clinical signs depends on the number of parasites ingested by the host animal over a short period of time. Cattle appear to be able to develop an immune reaction to fluke infestation, but sheep do not.

The acute form of the disease is more common in sheep than in cattle.

- It occurs 5 to 6 weeks after the ingestion of large numbers of metacercariae. There is a sudden invasion of the liver by masses of young liver flukes.

- Death takes place due to haemorrhage or liver failure, or both.

- The acute form of the disease is manifested by sudden death, or dullness, weakness, anaemia, lack of appetite, pain over the region of the liver and death in 48 hours.

- Because this is caused by migrating flukes which have not yet begun to lay eggs, no eggs are found in the faeces and diagnosis must rest on a post mortem examination.

- Post mortem will reveal a badly damaged, swollen liver. The liver membrane will have many small perforations and haemorrhages below it. The body of the liver will contain tracts formed by the migrating flukes and the liver will be light and damaged. Close examination will reveal the small immature flukes.

The sub-acute or chronic form of the disease is more common in cattle, but also occurs in sheep and can cause death in both. It is the result of activity of the adult flukes in the bile ducts, causing anaemia and protein leakage.

- Body growth is reduced, there is loss of weight, fluid accumulation in the jaw area (`bottle jaw`) and anaemia.

- Diagnosis is made by the finding of fluke eggs in faecal samples. These must be differentiated from those of Paramphistome rumen flukes.

- A post mortem examination will reveal large mature flukes in the bile ducts,which are usually thickened and which may be hardened in cattle, but not in sheep.

- There will be oedema, anaemia and often emaciation.

- Black Disease, caused by the multiplication of Clostridium Novyi in the tracts caused by migrating immature flukes is a disease of sheep aged between 2 - 4 years.

- Acute fluke infestation usually kills younger animals.This age difference is helpful in making a diagnosis.

Lung worms

Local names:

Gikuyu: njoka cia mahuri / Luo: oniambo

Gikuyu: njoka cia mahuri / Luo: oniambo

Order/Family:

Dictyocaulus species

Dictyocaulus species

Description:

Nematode infestation of cattle, sheep, goats and horses

Nematode infestation of cattle, sheep, goats and horses

Introduction

There are three species of lung worm infection that can cause major economic loss in livestock production: Dictyocaulus filaria, Dictyocaulus viviparus and Dictyocalus arnfieldi

These species are host specific in that D. filaria affects sheep and goats, D. viviparus affects cattle while D. arnfieldi affects horses and donkeys.

In addition, the lungworms Muellerius capillaris and Protostrongylus reufescens also occur in sheep and goats.

Dictyocaulus viviparus

This occurs in the bronchi of cattle, mainly in North Western Europe and especially Great Britain, but may also be found in cool highland areas in tropical countries. It is more prevalent in countries with cool climates and with marked seasonal differences in temperature. Such being the case lungworm infestations are not as common in tropical Africa as they are in temperate Europe. This must be borne in mind and any suspected infestations in cattle should be further investigated by a veterinarian.

It primarily affects dairy calves which have been reared indoors until 4-5 months of age and then placed in a paddock grazed each year by successive calf crops.

The male worm measures 4.5 - 5.0 cm while the female is 6 - 8 cm long.

The worm is a heavy egg producer and it is estimated that a single infested calf may contaminate a pasture with 33 million larvae.

The number of larvae on the pasture determines how severe the reaction in the host will be. The larvae are quite resistant to cold although cold weather delays their maturation.

Mode of spread

Outside the host, the larvae become infective in 6 - 7 days and infestation occurs by ingestion. Moisture and a moderate temperature are required for full development to the infective state. Larvae survive best in cool, damp surroundings. Under favourableconditions the larvae may survive on a pasture for over a year.

They are quite inactive and so any factor which assists in spreading the larvae, such as mechanical spreading of dung, a high concentration of animals, diarrhoea and local growth of fungi with their explosive discharge of spores, will favour infestation.

Larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and pass through lymphatic vessels, mesenteric lymph glands, then via the blood vessels to the lungs where they eventually mature in the air passages. The development from ingestion of larvae to maturation to adult worm takes about a month.

Infestation of calves with D. viviparus larvae confers immunity to subsequent infestation, so once infested, adults are generally immune.

Overwintered larvae or infested carrier animals are primarily responsible for ongoing outbreaks of the disease.

|

Signs of Lung worm Infestation

|

|

- Post mortem examination may reveal worms and froth in the lungs accompanied by oedema and damaged bronchi. Air may be present in the tissues of the lungs and the interseptal lymphatics may be enlarged and have a marbled (Insert dictionary) appearance. There is severe bronchitis together with pneumonia.

- Diagnosis is based on the clinical signs, the finding of larvae in the faeces, the risk factors and post mortem findings.

- In horses the worms do not mature so no larvae will be found in the faeces. Diagnosis must therefore rest with post mortem findings, the finding of larvae from donkeys on the pasture, a history of close contact with donkeys and the clinical symptoms.

- In affected calves the differential diagnosis includes Viral Pneumonia in which the cough is usually hard and rasping as opposed to the softer cough caused by the presence of lung worm infestation.

- It must be remembered that because only adult worms lay eggs which develop into larvae, affected animals may be ill for as long as 2 weeks before larvae appear in the faeces.

Lungworm infestation does not appear to be common in Kenya. This may be due to under-diagnosis. In any outbreak of coughing in calves, adult cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys and horses it should be regarded as a possible cause and incorporated into the differential diagnosis.

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Prevention and control

- Remove the affected animal from infected surroundings to clean dry areas.

- Separate young animals from mature animals

- Avoid lush wet paddocks

- Treat housed yearling (under two years old) cattle before they are released to grazing

- Vaccination of calves and mature cattle with oral X-irradiated vaccine is also effective.

- Oral vaccines are available in Europe with 2 doses given 4 weeks apart at least 2 weeks before the start of the grazing season. The oral vaccines are not available in the local market in Kenya in 2010.

- Anthelmintics such as ivermectin or doramectin can be used to prevent infestation, with 2 or 3 treatments given during the grazing season, the timing of which depends on local grazing practice. By disrupting developing infestations, they stimulate immunity to the parasite.

- Horses should not be grazed with donkeys

Treatment

- Early treatment of the larval lung worms with 10% solution of diethylcarbamazine at 55 mg per kilogram live weight administered intramuscularly for 5 days. This is useful when symptoms first occur but it is not effective against adult lungworms.

- Oral administration of tetramisole given at 15 mg per kilogram or subcutaneous injection with levamisole at 7.5 mg per kilogram is effective.

- Ivermectin, doramectin, moxidectin, fenbendazole, and albendazole are effective treatments against all stages of the lungworm in cattle, sheep and horses.

- In severe cases non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may also be indicated and where there is fever, antibiotics can also be used.

- If the infestation is massive and much damage has been done by larvae, treatment may not be effective. NB. Always follow the manufacturer's recommendation when using drugs for lung worm control.

Common traditional practices

- Samburu (cattle, goats, sheep): Grind a handful of fruits of seketeti (Lantana trifolia) very finely and mix with 1 litre of water. Drench.

- Luo (cattle, goats, sheep): Pound a 30cm long piece of fresh bark of ober (Albizia coravera). Put in the animal?s drinking water. Do not give the animal any other water.

- Turkana (camels, cattle, goat, sheep): Crush 1kg of eelim (Dyospyros scabra) seeds. Soak in 4 litres of water for 6 hours. Sieve and drench. Use 2 litres for adult cattle and half this amount for calves, goats and sheep

Round worms

Local names:

Embu, Gikuyu, Meru: njoka / Gabbra: beni segara / Kamba: nzoka sya nda / Kipsigis: tiongik / Maragoli: tsinzoka / Samburu: ntumuai / Somali Ethiopia: goryan / Turkana: ngílomun /

Embu, Gikuyu, Meru: njoka / Gabbra: beni segara / Kamba: nzoka sya nda / Kipsigis: tiongik / Maragoli: tsinzoka / Samburu: ntumuai / Somali Ethiopia: goryan / Turkana: ngílomun /

Common names:Nematodes

Description: Intestinal parasite

Introduction

Round worm infection, also called parasitic gastroenteritis, can cause major economic loss in cattle, sheep and goat production.

Several different species of worms with differing life cycles may be involved, but the symptoms they cause are all rather similar and difficult to differentiate in the living animal.

The worms are generally round, cylindrical, pointed at both ends and have a smooth, white, shiny cuticle. Each individual worm is male or female. They vary in length from being easily visible to being almost invisible. Their body structure comprises an alimentary canal which starts with the mouth and is followed by the intestines and ends in the rectal opening near the tail.

The worm feeds through the mouth and passes the food to the intestines where nutrients are absorbed through the intestinal wall. The reproductive organ of the male worm consists of a long tube through which the spermatozoa are pumped. The female worm has the ovary and uterus in the same position as the reprodutive organs of the male. Male worms are assisted in mating by spicules which they use for attachment to the female. The spicules also direct the flow of sperms. In all cases, the male worm is smaller than the female.

Young animals are generally more at risk than adults, but in sheep adults are susceptible, especially ewes after lambing when there is a rise in faecal egg counts with diarrhoea and milk supression due to a relaxation in the ewe's immunity. Sheep seem to be more susceptible to the effects of worms than other livestock and clinical disease is more common. Immunity is acquired slowly and is generally incomplete.

When treating animals with symptoms, the following should be considered:

- Provide adequate nutrition

- Treat all animals in a group as a preventive measure in order to reduce further pasture contamination

- Following treatment stock should NOT be moved to clean pasture as was previously recommended. The reason for this is that if any parasites with resistance genes survive treatment then the clean pasture will become seeded with a wholly resistant population of worms.

Resistance to drugs that expel the worms (anthelmintic resistance) is a major problem. Overuse of drugs, random use of drugs without a proper disgnosis, improper dosage, underestimation of body weight, poor nutrition and rapid reinfestation all play a part in causing resistance.

In some countries, such as Australia and South Afrca, anthelmintic resistance is such a serious problem as to have a major impact on the viability of sheep rearing. Such a situation must not be allowed to develop in Kenya.

Life cycle

The life cycle of the worms can take 2 to 3 weeks, but may be delayed by variations in temperature:

- Eggs are laid by the parasite.

- Eggs are passed in the faeces of the animal onto the herbage.

- Out of these eggs hatch larvae

- Larvae are then ingested by the host.

Nematode parasites of cattle and sheep

1. Toxocara vitulorum

Is a type of round worm which occurs in the intestines of cattle and is present in most tropical countries. The worm has a thin transparent outer cover. Infection is more serious in calves than in mature cattle. Prenatal infection is very common. The worm has a direct life cycle whereby the eggs are swallowed and hatch inside the host. The larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate to other tissues of the host especially the lungs, via the blood stream. The larvae are coughed up and then re-swallowed and then re-enter the intestines. The larvae moult and become adult worms in the intestines where they produce eggs.

2. Haemonchus contortus

This is also called the barber pole worm. It is a common stomach worm of cattle and sheep. It is mainly found in the fourth division of the stomach (abomasum). The worm is distributed all over the world. It has a direct life cycle. The larvae are ingested by the host. Infective larvae can survive for several weeks in pasture under suitable climatic conditions. After the larvae are ingested by the host, they settle in the mucous membranes of the abomasum and pass through the fourth larval stage and become adult. The adult worms mate and the female worm passes eggs in the faeces of the final host.

| 3. Trichostrongylus species

There are several species of this worm widely spread in the tropics. The worm is brownish, pinkish in colour and is found in the abomasum and small intestine of cattle and other species of domestic animals. They have a direct life cycle similar to Haemonchus contortus. Infective larvae are ingested and settle in the alimentary canal of the host.

|

|

These are small, red coloured worms found in the small intestine of most ruminant animals. They have a direct life cycle similar to Trichostrongylus.

5. Ostertagia species

They are mainly found in the abomasum and occasionally in the small intestine of livestock. They have a direct life cycle and are able to survive longer outside the host even under harsh conditions.They normally infect pasture during the onset of the long rains.

6. Nematodirus species

They are found in the small intestine of livestock. The eggs develop outside the host and the larvae hatch at the infective stage. The larvae develop to maturity inside the host.

7. Chabertia species

They are also known as the large mouthed bowel worms. They are found in the colon of most ruminants. They have a direct life cycle and infection of the host is by ingestion of the infective larvae. The larvae penetrate and embed in the wall of the colon. The adult worm passes eggs in the faeces of the host.

Signs of Roundworms

The signs of round worm infection are shared by many diseases and conditions, but based on certain symptoms, grazing history, and season, a presumptive diagnosis can be made.

- Young animals are most often affected, but adults not previously exposed to infestation frequently show signs and succumb. Animals in a state of poor nutrition are more sucseptible than animals in good condition.

- Ostertagia and Trichostrongylus infestations are characterised by profuse watery diarhorrea which is usually persistent but in infestations by Haemonchus there is often constipation.

- Both produce variable degrees of anaemia.

- In sheep the conjunctiva (the mucous membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelid and the exposed surface of the eyeball) can be snow white in colour.

- There is often progressive weight loss, weakness, a rough coat, loss of appetite, and oedema, particularly under the lower jaw - a condition termed as bottle jaw.

- Ascarid infestations such as that caused by Toxocara can result in rapid breathing and coughing. This is usually only seen in young animals.

- Note that egg counts are not always an accurate indicator of the number of adult worms present as egg laying is not always constant; some species of worms lay more or less eggs than others, and immature worms and larvae are not egg layers. But they still are capable of causing significant clinical symptoms, and even death.

- Some worms are much more pathogenic than others. For example 100 Haemonchus worms in a lamb do as much damage as 5,000 - 10,000 Ostertagia worms.

Post mortem findings

Post mortem examinations are the most direct method of diagnosing parasistic gastroenteritis, as adult worms are usually visible to the naked eye. Some are more easily seen than others. For example, worms of the species Haemonchus, Bunostomum, Oesophogostomum, Trichuris and Chabertia are easily seen, whereas Ostertagia, Trichostrongylus, Cooperia and Nematodirus are difficult to see, except by their movement in fluid digesta.

- The mucus membranes are often pale.

- The carcass may be emaciated, but in some instances where an animal has been overwhelmed by a sudden massive invasion of larvae the carcass may be in good condition.

- The abomasum is frequently fluid filled and this may exend into the small intestine, especially in Haemonchus infestations.

- The liver is pale and fragile

- The alimentary tract will reveal worms when opened. Check the abomasum especially, and the large intestine.

- The intestinal contents may be reddish brownish in color.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis should be done by qualified personnel able to identify the type of worms present and to give appropriate advice.

Prevention - Control - Treatment

Round worm infestation can be controlled through adherence to the following measures:

- In young cattle round worm infection can be controlled by the use of broadspectrum anthelmintics (drugs to expel worms) in conjunction with pasture management to limit reinfestation.

- Pasture management includes a move to clean pastures e.g. grass conservation areas or hay aftermath, or alternate grazing with other host species, or integrated rotational grazing in which susceptible calves are followed by immune adults.

- A special strategic treatment is required in sheep to counter the postnatal relaxation of immunity seen in ewes. Treatment within the month before and the month after lambing should be given. Supportive management after treatment includes movement of sheep from contaminated pastures to cattle pastures, grass conservation areas, or pastures not grazed by sheep for several months. This period may vary from several weeks to several months depending on the weather pattern (longer if wet and cool, shorter if dry and hot).

- Resting pasture for more than 10 weeks will reduce the number of infective larvae on pasture. Separating young and mature animals in grazing paddocks or grazing different species of animals together. These practices will help to reduce parasite mass and reduce infestation levels.

- Better grazing management should avoid overstocking of animals on a particular paddock. Grazing management should also ensure that there are alternative grazing areas, should avoid damp grazing areas and always ensure that animals are in good condition. Well nourished animals are less likely to acquire heavy worm infestations.

Treatment

The following treatments and drugs are recommended for round worms.

- Albendazole - trade name Valbazen should be administered orally at the end of the cold season and beginning of the dry season. The drug should be given at the rate of 10 mg/kg body weight

- Fenbendazole - trade name Panacur should be given at the end of the cold and beginning the dry season by mouth at the rate of 8 mg/kg body weight

- Ivermectin - trade name Ivomec can be used in different forms such as injection, orally, or as a pour on. Should be given at the rate of between 0.2 - 0.5 mg/kg body weight as a subcutaneous injection. Giving anthelmintics by injection is recommended as it avoids the risk of damage to the animal's throat through rough administration and none of the drug is lost.

- Levamisole and oxyclazanide mixed- trade name Nilzan should be given by mouth at 0.25 ml/kg body weight

- Albizidal antihelmintica as a botanical treatment- the leaves of the tree are fermented and sieved and administered orally. NB. Always follow the manufacturer?s recommendations when administering drugs.

Common traditional practices

Though traditional wormcure is practiced widely, reports have also been shared where traditional treatment has killed the animals under treatment. Dosage is very difficult as active content of plants vary depending on season and stage of growth. It is safer to use the commercial products with known dosis rate. If this is not available seek advice from the local herbalist.

- Luo (cattle, goats, sheep): Cut about 2kg of fresh awayo (Rhus vulgaris) roots, put in 1kg of water and leave overnight. Sieve and drench with 0.5 litre once a day for a week. Give half this dose for calves, goats and sheep. Give when it is cool and after the animal has eaten.

- Embu / Gikuyu (cattle, goats, sheep): Collect 2 handfuls of dry seeds of mugaita (Rapanea melanophloeos). Crush and mix with 1 litre of water. Boil gently for 20 minutes. Allow to cool, then drench once. For goats, sheep and calves use 500ml; for large animals use 1 litre. Drenching should be done in the evening when it is cool. Repeat after 2 weeks.

- Kipsigis (cattle, goats, sheep): Crush 0.25kg of matakarek (Rapanea melanophloeos) and mix in 1 litre of water. Let boil for 15 minutes. Allow to cool then drench the whole amount once. For small animals use 500ml; for large animals use 1 litre. Repeat after 3 weeks.

- Samburu (camels, cattle, goats, sheep): In the rainy season drive animals to areas with salty soils when the water has dried up. The animals will lick the salt from the surface of the ground.

- Maragoli (cattle, goats, sheep): Chop 2 bulbs of saumu (Allium sativum) and mix with 4 litres of water. Drench with 0.5 litres twice in 1 day. This treats worms and liverflukes. The dose is the same for adult cattle, sheep and goats.

- Somalia Ethiopia: Grind 2 fruits of Gosso (Hagenia abyssinica) in 0.5 of water . Drench a sick cow with this before it goes to pasture. Use half the amount for goats and sheep.

Review process

2. Hugh Cran , Practicing Veterinarian Nakuru. March - Oct 2010

3. Review workshop team. Nov 2 - 5, 2010

- For Infonet: Anne, Dr Hugh Cran

- For KARI: Dr Mario Younan KARI/KASAL, William Ayako - Animal scientist, KARI Naivasha

- For DVS: Dr Josphat Muema - Dvo Isiolo, Dr Charity Nguyo - Kabete Extension Division, Mr Patrick Muthui - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Isiolo, Ms Emmah Njeri Njoroge - Senior Livestock Health Assistant Machakos

- Pastoralists: Dr Ezra Saitoti Kotonto - Private practitioner, Abdi Gollo H.O.D. Segera Ranch

- Farmers: Benson Chege Kuria and Francis Maina Gilgil and John Mutisya Machakos

- Language and format: Carol Gachiengo

Information Source Links

- Barber, J., Wood, D.J. (1976) Livestock management for East Africa: Edwar Arnold (Publishers) Ltd 25 Hill Street London WIX 8LL

- Blood, D.C., Radostits, O.M. and Henderson, J.A. (1983) Veterinary Medicine - A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and Horses. Sixth Edition - Bailliere Tindall London. ISBN: 0702012866

- Blowey, R.W. (1986). A Veterinary book for dairy farmers: Farming press limited Wharfedale road, Ipswich, Suffolk IPI 4LG

- Force, B. (1999). Where there is no Vet. CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-0333-58899-4

- Hall, H.T.B. (1985). Diseases and parasites of Livestock in the tropics. Second Edition. Longman Group UK. ISBN 0582775140

- Handbook on Animal Diseases in the Tropics 4th Edition Sewell & Brocklesby

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: General principles. Volume 1(Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN: 0333612027

- Hunter, A. (1996). Animal health: Specific Diseases. Volume 2(Tropical Agriculturalist) - Macmillan Education Press. ISBN:0-333-57360-9

- ITDG and IIRR (1996). Ethnoveterinary medicine in Kenya: A field manual of traditional animal health care practices. Intermediate Technology Development Group and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 9966-9606-2-7.

- Merck Veterinary Manual 9th Edition

- Pagot, J. (1992). Animal Production in the Tropics and Subtropics. MacMillan Education Limited London

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 50 July 2009

- The Organic Farmer magazine No. 51 August 2009

Back

Back